Andrea Del Sarto prised at the Frick but his masterpiece is yet to be discovered

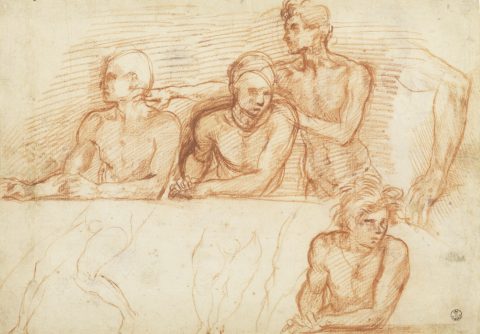

- Andrea del Sarto, Studies of figures seated and standing behind a table, about 1526 – 1527, red chalk 25.6 x 36.3 cm (10 1/16 x 14 5/16 in.). Istituti museali della Soprintendenza Speciale per Il Polo Museale Fiorentino.

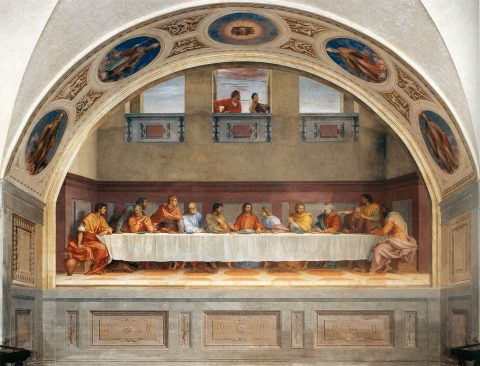

- Andrea del Sarto, Cenacolo, ca. 1511-1527, Chirch of San Salvi, Florence.

- Andrea del Sarto, Study of a Young Man (verso), ca. 1517–18, red chalk 5 1/8 x 4 15/16 inches. Galleria degli Uffizi, Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe, Florence by permission of the Ministero dei beni e delle attività culturali e del turismo.

- Andrea del Sarto, Portrait of a Young Man, ca. 1517–18, oil on canvas 28 1/2 x 22 1/2 inches. National Gallery, London © The National Gallery, London.

- Andrea del Sarto, Head of Saint John the Baptist, about 1523, black chalk33 x 23.1 cm (13 x 9 1/8 in.). National Gallery of Art (Washington, D.C.),

- Andrea del Sarto, Saint John the Baptist, about 1523, oil on panel. Unframed: 94 x 68 cm (37 x 26 3/4 in.).Istituti museali della Soprintendenza Speciale per il Polo Museale Fiorentino.

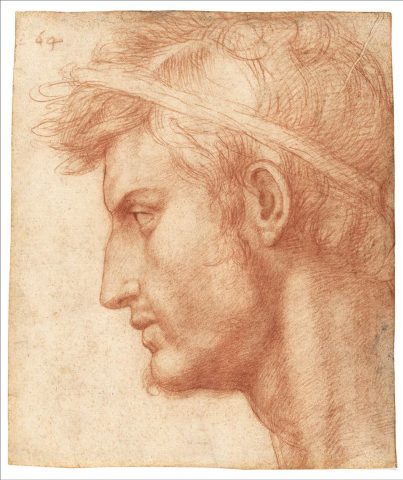

- Study for the Head of Julius Caesar, ca. 1520, Red chalk 8 7/16 x 7 1/4 inches. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, partial and promised gift of Mr. and Mrs. David M. Tobey. ©The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY.

- Andrea del Sarto, Study of the head of an old man in profile, about 1520, red chalk23.9 x 27.7 cm (9 7/16 x 10 7/8 in.). Owner: Kupferstichkabinett, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz. Photo credit: bpk, Berlin / Kupferstichkabinett, Staatliche Museen, Berlin, Germany / Photo: Volker-H. Schneider / Art Resource, NY.

It is a moment of international glory for Andrea del Sarto (1486-1530), important Italian Renaissance painter, master of renown artists such as Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino, but perhaps not duly known outside his own country.

Last summer the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles co-organized with the Frick Collection in New York, and in association with the Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe at Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence, a major exhibition dedicated to the artist, the first one ever presented in the United States. The same show has opened at the Frick Collection in New York last October and will be on until 10 January. At the same time, the Metropolitan Museum is also paying attention to the Italian artist with a focus on his “Borgherini Holy Family”.

The survey at the Frick Collection is titled “Andrea Del Sarto: The Renaissance Workshop in Action”. Through 45 drawings and 3 paintings – many on loan from some of the most important collections in the world, like the National Gallery, the British Museum and the Uffizi, just to name a few – the show aims at dismantling the creative process of the artist, thus disclosing the central role that drawing played in his modus operandi.

There are still many drawings by Andrea del Sarto that survived to this day; red and black chalk drawings, some of which are preserved at the Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe. They do represent the very heart of Andrea del Sarto’s creative process, especially as far as the conception of the so dynamic and passionate figures that you can see in his paintings is concerned, which would have later influenced his most talented pupils.

A similar international interest was paid to Andrea del Sarto just after his death, when around the middle of the XVI century, the etcher and publisher Hieronymus Cock was successfully selling in Europe reproductions of artworks by prominent artists like Bosch, Raffaello, Bronzino and, indeed, Andrea del Sarto. After all, the same Andrea had showed, throughout his life, an ambition to travel the world with his art. In 1518 he left Florence for France, heading to the court of Francis I. His “Charity” (now at the Louvre) adorned originally the rooms at the Château d’Amboise, to then be passed to the Château de Fontainebleau where it is believed it hung in the bathrooms of the castle, as quoted by various sources. His staying in France however only lasted one year. Urged by his wife Lucrezia (married in 1517, and always represented by the painter in his female figures), Andrea del Sarto went back to Florence in 1519, thus ending his cosmopolitan ambitions.

This important exhibition in New York offers us the occasion to go back to Florence and to focus our attention on a masterpiece by Andrea del Sarto: a not too popular fresco, yet considered by scholars as a masterpiece in the artist’s production.

Amongst the works on show at the Frick collection, there is indeed a very meaningful red chalk drawing, described in the caption as “Studies of figures seated and standing behind a table”, which can be dated around 1526-27. According to the evidence, the drawing was a preparatory study for a “more impressive fragment” of a most neglected fresco Andrea Del Sarto painted at the refectory of the former Vallombrosan monastery of San Salvi, in Florence, where the artist repeatedly worked between 1511 and 1528.

Legend has it that during the Siege of Florence, in 1529, the soldiers in charge of razing to the ground convents, hospitals and buildings outside the city walls were so awe-struck by the beauty of the work, that they spared the monastery. The artwork has been so well preserved to the extent that we can still discern, for instance, the artist’s research on colours (in this phase of his production, the chromatic range appears to be brighter and more vivid, with shimmering effects, for example, on Judas’ robe).

As there is a vast specialist literature on San Salvi’s work, our article doesn’t aim at going any deeper into this. However, we would like to stress how such a high example of sixteenth-century painting is nowadays almost ignored: it is rarely regarded as a fundamental stopover on an artistic tour of the city of Florence. Despite the building which hosts the masterpiece has been turned into “Museo del Cenacolo di Andrea del Sarto” in 1981, there are still few visitors who pass by that destination.

In this regards, we would like to go back to the words of former director of Uffizi in Florence, Antonio Natali, whom we interviewed in 2013 on the occasion of the book “Scene da un Patrimonio” (Antonio Carnevale and Stefano Pirovano, Galaad), a research on Italian cultural heritage . “In your opinion are there too many museums in Italy to be able to manage them properly? Do you think the system needs to be in any way rethought?” we asked Natali. Here is his meaningful answer: “Yes, there are indeed too many museums. If instead of economizing at the expenses, new museums are opening, it does mean that there is no actual idea of how much it costs to maintain them. However, amongst the multitude of museums in Italy, there are extraordinary important places little known to the people. Let me just give you an example: the Florentine museum of the Cenacolo of San Salvi, where one of the most significant paintings of the XVI century is located, the Last Supper by Andrea del Sarto, by the way perfectly kept, indeed one of the last best preserved Last Supper’s. Well, if the Cenacolo is visited by 100 people per year, rather than 100.000, is mainly because we keep on promoting exhibitions which present idols to venerate rather than artworks to understand, thereby overlooking the real gems, those considered minor ones.”

Natali’s answer embodied an explicit argument about those exhibition which tend to emphasize only few famous artists and about a cultural policy at the expenses of the real masterpieces which on the contrary need to be rediscovered. “In such a vicious circle – continued the then director of the Uffizi- with blockbuster exhibitions and sublime forgotten places, it proves to be hard to involve private sponsors, who will unlikely invest money with no guarantee of future returns. Authentic treasures, without being appraised, have been left to their own devices.”

A high value is then to be placed on shows like the one now at the Frick Collection, which have boldly brought to light a great artist by focusing on crucial topics, albeit of unconventional genres, like drawing, in the case of Andrea del Sarto. It is also an invite to rediscover the Museo del Cenacolo: only 2,7km away from Piazza del Duomo (Cathedral square), at 16 San Salvi street. When you enter the museum, your gaze will open up to many perhaps unfamiliar, yet remarkable artists like the Franciabigio, Giovanni Antonimo Sogliano, Michele di Ridolfo, Ridolfo del Ghirlandaio, Francesco Brina, Raffaellino del Garbo, il Poppi, il Ceraiolo, il Bachiacca, Francesco Foschi, Giuliano Bugiardini.

November 25, 2020