A curator is born: a look at Kenya’s first curator’s workshop

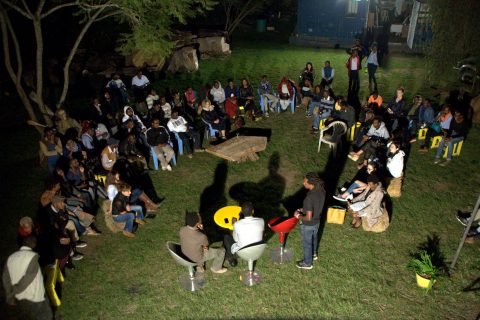

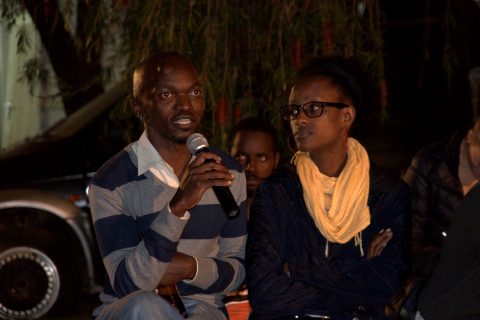

- Azu Nwagbogu’s curators talk at Kuona Trust, Nairobi.

- Azu Nwagbogu’s curators talk at Kuona Trust, Nairobi.

Until recently, the number of curators in Kenya could be counted on one hand. Two, if you were kind. The definition of a curator was vague; in different spaces it meant different things.

Despite a growth spurt within the arts, very few synapses are fired between the Nairobi art axis and the larger Kenyan population. Most people have never heard of a curator, others are still digesting the concept, while only a small fraction of art enthusiasts recognize curators from Africa and beyond. But even though it seems as though Kenya is lagging in its initiation in to curatorial practice, the blind spot is not Kenya specific. Across the globe, friends of the arts are only just awakening to the full potential of art curators, master connectors who work behind the scenes to change how we filter and fathom reality.

With today’s vast production of artwork, there is certainly a need for more experts to make sense of it all and the curator holds a special place in the art world. In a Guardian article entitled Hans Ulrich Obrist: the Art of Curation, Obrist describes the role of the curator as a catalyst for an extraordinary experience. “Today, curating as a profession means at least four things. It means to preserve, in the sense of safeguarding the heritage of art. It means to be the selector of new work. It means to connect to art history. And it means displaying or arranging the work.” Today, curating is clearly more than hanging an exhibition.

African superstar curators Okwui Enwezor from Nigeria, who recently curated the 56th Venice Biennale, or Simon Njami of Cameroonian descent, who directed Edition 12 of the Dakar Biennale, Dak’art, impress their audience through their multi-part practice. A recent Curator’s Workshop in Kenya focused on what a number of African curators are doing to evolve the consciousness about art, history and art-history emanating from Africa.

Through Nairobi’s Goethe-Institute, eight talented individuals were invited to participate in Kenya’s first official Curator’s Workshop, which began June 20th. The five week course was lead by internationally acclaimed African curators. With different approaches to their curatorial practice, both Azu Nwagbogu from Nigeria and Raphael Chikukwa from Zimbabwe spoke about the influence that African curators are having on the way we perceive ‘Africa’ and ‘African art’. Contemporary African curators are using their voices to expel certain stereotypes. “If you don’t tell your story, it will be told by someone else,” says Chikukwa. “Curators must rewrite history so we are no longer passengers in our own ship.”

But the proverbial conundrum persists: What exactly does it mean to be an ‘African’ curator? It is frustrating and awfully confining to be pegged by a nationality or worse, by an entire continent. Naturally, curators want to be recognized for their directorial and aesthetic capacities. Then how important is it for contemporary curators to convey the nuances of modern-day African existence? For example, the complexities of the lives of people living in Lagos, of which the rest of the world has no understanding because they only know a daunting, one-sided view of the place. Of course, it is not the responsibility of every curator to pursue this objective; but it is critical that some hands, whether intentionally or unconsciously, work to create new and accurate representations that take over the old.

Curator Azu Nwagbogu advises his trainees not to be diminished by semantics or nominal categorizations. “Why are we so insecure about the African label? Don’t be defensive. Instead, use these platforms to present a meaningful message.” Basically, he says that if your work is persuasive, you will already have everyone’s attention. It is at that point that you can disclose your character if you like, but by then it will be evident that you are not what people first thought. Nwagbogu encourages curators to take advantage of opportunities to showcase the highly conceptual and unexpected talent coming from what has too long been seen as the Dark Continent. There is a lot of good art coming from Africa that is neither ‘naïve’ nor ‘primitive’ in effect, nor is it inundated with recycled parts, masks or feathers.

As Director of African Artists Foundation and curator of Lagos Photo Festival, Azu Nwagbogu hopes he is, “fostering an accelerated disambiguation of the identities and ideologies of the art scene and art market.” He says the conflation he sees “has an adverse effect on the emerging art scene.” What he means by this is that it is when we show the different shades of grey within the diverse pockets of African art and culture, people will stop grouping Africans as a single identity. By investigating the scene thoroughly and exposing the minutiae and the charming intricacies, we begin to dissolve the misunderstandings that exist around the people, places, lifestyles and ideologies. A good curator can help achieve this.

Nwagbogu recently curated the exhibition Dey your Lane – Lagos Variations! at the Bozar Centre for Fine Arts in Brussels, Belgium, which ran from June 17th to September 4th, 2016. ‘Dey your Lane!’ is a useful expression in Lagos meaning ‘mind your own business.’ He used photography, video and sound installation to explore the mounting population in Lagos, which lends itself to many ways of life. His current exhibition Tear my Bra, at the Arles Photography Festival in Paris, France, illustrates how Nollywood, Nigeria’s thriving film industry, is impacting visual storytelling in Africa. The exhibition runs from June 4th to September 25th.

Advising many of the artists he works with, Nwagbogu says they must first satisfy their souls through their art; that the audience can detect the artist’s authenticity. “Tell your stories without deleting your past,” he encourages them. “Be honest and bring yourself in to your work.” Nwagbogu applies similar principles to his curatorial practice. “Zoom in to the details of your study and have a candid conversation. Do it in a systematic way but with aesthetic sense and good taste.” Azu Nwagbogu led the first two weeks of the Curator’s Workshop in Nairobi. He met with many Kenyan artists at the Kuona Trust Arts Centre, where he also gave a public talk on art and curating.

Chief Curator of the National Gallery of Zimbabwe since 2010, Raphael Chikukwa is the founder of the Zimbabwe pavilion at the Venice Biennale. Leading the last three weeks of the Curator’s Workshop, he focused on educating emerging curators on the politics of curating African art. Looking at the biennales in Africa, the exhibitions that have been successful and those that have made curators scratch their heads, the contemporary online platforms dedicated to African art, the African museums and quality publications on African artists, Chikukwa showed his students how curating has moved from a casual disposition to an academic course and a very serious enterprise that, if done right, has the potential change the way we filter the world. He sees the curator as a story-teller who repackages information in innovative, alluring ways to keep our attention and to bring us new options.

Wearing a different curio-style necklace every day, Chikukwa is a rather distinctive character who refuses to wear a suit or conform to Western expectations of what a curator might look like. Though he no longer keeps dreadlocks, he continues to dress as he sees fit without bowing to the corporate fashion gods. Taking care of over ten thousand works of art at the national gallery and working with the likes of Tapfuma Gutsa and other world-renowned artists, it is Chikukwa’s mission to showcase talent from Africa. He says the problem in the past was that, “We have not been able to harness our own contributions because we have always taken a back seat.” Chikukwa encourages young curators to make up for lost time and take full advantage of the fact that the world art lens is looking at East Africa right now.

Being a curator is no longer about selecting and mounting or taking care of artwork. Today’s curators knowledge producers, many of whom snuff out those forced stories or distorted accounts in history that we have always accepted as fact. Rewriting our stories, the curator is the new narrator, telling you what really happened, what is happening and what the future holds. Whether it is a solo show or a joint exhibition, the curator selects artwork that makes the most compelling argument for the theme being investigated. And just as the artists do, it is also the curator’s objective to be as creative and resourceful as necessary to produce a dynamic, ongoing conversation about the issues being addressed via the exhibition.

So what do the new curators offer Nairobi? While the academics continue to question whether the relevance of curators in Kenya differs from elsewhere in the world, the artists appear to be glad to have the guidance. But is a curator born or made? Is there any guarantee that Nairobi’s new curators will be good at what they do? In the best case scenario, each participant already had an innate gift for curating that was further refined through the workshop. Worst case scenario, they all have a better understanding of the basic functions of a curator and what is happening within the arts across the continent.

Note: This article was written by artist and art writer Zihan Kassam who has curated exhibitions and was invited to the Curator’s Workshop as a student not a reporter. The other students certified from the workshop are Rose Jepkorir, Wambui Kamiru Collymore, Thom Ogonga, Mbuthia Maina, William Ndwiga, Don Handah and Nyambura Waruingi. Sylvia Gichia and Paul Onditi advised the panel and visited during classes and at the curator’s final presentations.

September 11, 2016