“I’ve always done parodies of what a painting is supposed to be”

Ashley Bickerton first retrospective show is taking place in New York. CFA interviewed the artist to understand what happened to his art during the past 30 years.

- Ashley Bickerton. Abstract painting for people #3, 1986. Acrylic and metal flake enamel on plywood with Formica and brushed aluminum, 42 x 72 x 11 inches (106.7 x 182.9 x 27.9 cm). Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong.

- Ashley Bickerton. Extradition with Computer, 2006. C-print in mother of pearl inlaid artist frame, 36.18 x 43.87 inches (print) (92 x 111.5 cm) (print), 43.25 x 51.5 inches (110 x 130 cm) (framed). Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong.

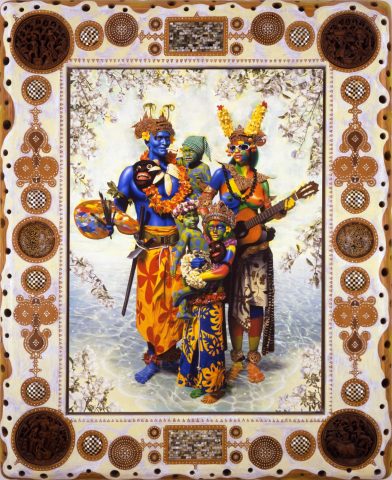

- Ashley Bickerton. Famili, 2007. Acrylic and digital print on canvas in carved wood, coconut, mother of pearl and coin inlaid artist frame, 86 x 72 x 7 inches (218.4 x 182.9 x 17.8 cm). Lindemann Collection, Miami Beach.

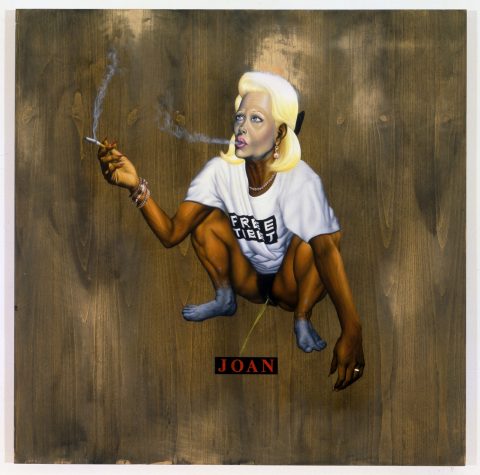

- Ashley Bickerton. Joan and the Cosmos, 1996. Oil, acrylic, and pencil on wood, 47.25 x 47.25 x 2 inches (120 x 120 x 5.1 cm). Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong.

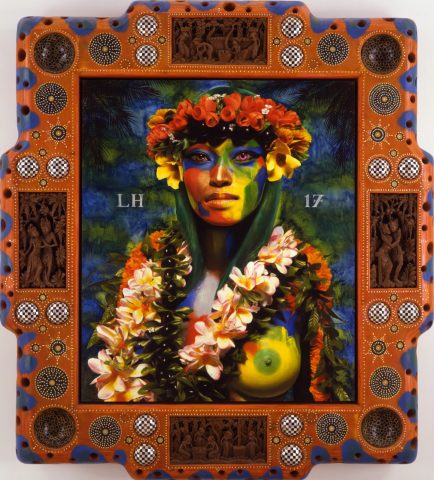

- Ashley Bickerton. LH 17, 2007. Oil and digital print on canvas in carved wood, coconut, mother of pearl and coin inlaid artist frame, 80 x 72 x 7 inches (203.2 x 182.9 x 17.8 cm). Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong.

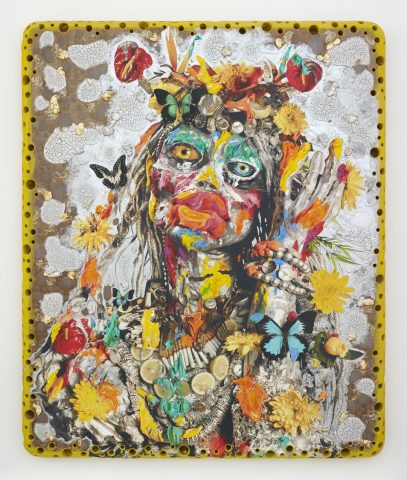

- Ashley Bickerton. M-DNA_eve 1, 2013. Oil and acrylic on digital print on wood, 88.5 x 74.5 x 5 inches (224.8 x 189.2 x 12.7 cm). Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong.

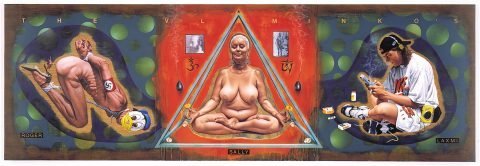

- Ashley Bickerton. The Vlaminkos, 1998. Oil, acylic, and pencil and photographs on wood, 48 x 144 x 3 ¼ inches (71.12 x 365.76 x 8.23 cm). Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong.

- Ashley Bickerton. Tormented Self-Portrait (Susie at Arles), 1987-1988. Synthetic polymer paint, bronze powder and lacquer on wood, anodized aluminum, rubber, plastic, formica, leather chrome-plated steel and canvas, 89.41 x 68.7 x 15.75 inches (227.1 x 174.5 x 40 cm). Collection of The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong.

- Ashley Bickerton. Wall-Wall SnS-S, 2017. Oil And meta-flake enamel on resin and fiberglass on plywood with aluminum, 185 x 155 x 20 cm. Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong.

Born in Barbados and raised in Hawaii, Ashley Bickerton moved to New York in 1982 after graduating from Cal Arts and quickly became a rising star in the explosive art scene of the time. A prominent player the Conceptual Art movement dubbed Neo-Geo, Ashley Bickerton pulled up stakes and moved to Bali in 1993, where he dramatically changed his style of working by embracing figurative art while parodying island culture. With the first American survey of his 30-year career on view at The FLAG Art Foundation in New York, the artist spoke to Conceptual Fine Arts about his insightful work from his studio on the other side of the world.

You grew up in a family that was always on the move, because of your father’s profession as a linguist studying in the field. How do you think that constant travel has impacted your work?

In a sense, I don’t belong anywhere, and I think that’s part of the work. Culturally, geographically and racially I’ve always been out of context and I’ve even chosen to live in a place where I’m the other, the outsider.

Some of the earliest works in the FLAG show are from your legendary Susie series, which flaunt symbols and logos while painting an autobiographical picture. How did you come to making these works?

There are a number of things that conspired to push me in the direction that I formerly went in and some of those were forces that were less likely to stick, less welded to my temperament. They were more to do with the moment in time and other things are much more related to my hardwiring. For the things that conspired you have to remember where we came up. When I arrived in New York I was coming out of Cal Arts and I almost immediately started working for Jack Goldstein. So there was a direct conduit to a then-in-place de facto cultural mafia. At the same moment there was the Neo-Expressionist ascendency and that machine was sort of loud, grinding along, hissing and bubbling in place and demanding a lion’s share of the creed lights. As a young artist coming up we are temperamentally bound to thinking in terms of us and them and battle lines and things like that. At this later stage in my life it seems quite humorous but back then some of the things that pushed me in that direction were a reaction against things like Neo-Ex and post-graffiti art. I moved consciously toward a colder, more conceptually based, more post-minimal stance—whether or not it was my own natural voice, times bears that out. I’ve spent a lot of time since then playing around with the idea of what is my natural voice. But those kind of things conspired to lead us there and back then the East Village scene was this protean germinating machine, which so much came out of. We had this real conscious sense of us vs. them, and battle lines were literally drawn across the alphabet avenues. There was turf. There was a sense of taking them down. What seems funny all of these years later is that the people I considered the enemy back then I actually like now and people that are supposedly my own allies I say really? What did I see in it?

At the time you were part of a movement called Neo Geo (short for Neo Geometric Conceptualism) that included Jeff Koons, Peter Halley, Meyer Vaisman, Haim Steinbach and others. Neo Geo never seemed like the right tag to me. Looking back, what’s your take on that period and its label now?

I believe it was Jeffrey Deitch who coined he term and with his tongue deeply planted in his cheek. None of us — save one, possibly — liked it at all. It was a moment that was defined by whoever had the platform and at that time it was Peter Halley and his relationship to Baudrillard, amongst other writers and continental theorists, The procession of simulacra seemed to be an idea that was very central to that particular dialogue. Neo-conceptualism was a bit banal, but actually better. The term that I liked was Commodity Art, because that was what I was trying to zero in at the time and I thought that the two other artists that I was interested in in that moment — Steinbach and Koons — were doing exactly that. When they took an object directly out of its box — in its hermetically sealed state of perfection and before it went into utilitarian usage — they froze it at that moment, whether it was in a vitrine, a tank or on a shelf. It’s a moment in consumer culture that’s based on the moment of spiritual connection. I found that very interesting.

Do you think this societal fascination with consumerism was a result of the supposed economic prosperity of the Reagan years?

Yes, none of us from my universe were too thrilled when we just elected this latest personage into the White House, but I did have some of my most productive years under Reagan. Maybe it can be that way again, but so far, no. This current chapter is absolutely soul sucking and depleting. It’s very hard to gain a focus or even voice an opposition, other than joining Antifa. I’ve become obsessed with Antifa because that’s what Trump has almost led me to.

Your 1986 piece Abstract painting for the people #3 seems to depict silhouettes of toilets. Is that a comment on art as a commodity or of consumerism being a load of shit?

Yeah, it’s indoor plumbing. It’s actually my comment on Neo Geo. I’ve always had this approach to art that when people keep saying that you are something and you keep saying “No, I’m not, I’m not,” finally you say “Okay, if you want it, I’ll be that.” So you go and do it and turn it into high camp. All of these years later I realized that two of my driving forces have been parody and camp, which is kind if a hard mix for someone who comes out of Conceptual Art. I’ve always done parodies of what a painting is supposed to be. That is, anything but a real painting—it just sort of skirts around it in every way without actually quite landing where it’s supposed to land.

When you moved to Bali in 1993 your work started to change to figurative representations of life. Was this change environmental or an evolution of ideas?

There are a couple of answers to that question. When I did my first show after coming to Bali it took me three years to make. I came here in 1993 and my first solo show was in 1996. It was kind of really dark subject matter—cannibalism and all sorts of twisted stuff. People said “Oh my God, the Island of Doctor Moreau.” He’s run off to some crazy place and gotten all kinds of crazy ideas. Well, no actually. I had the entire show cooked and baked in my brain before I left New York. It was actually necessary to leave New York because I had gotten to a point in the city where there were just so many damn social obligations. You’d actually start checking on next week four days ahead to see if it was clear, especially when you work at night. Openings are from 6 to 8 and you’ve got to go to every ex-assistants and his spouse or ex-spouse’s show and you have to start lining up what you can’t get around and if you work at night it’s right in the middle of your work day so you can just piss everything goodbye. In order to do the kind of work that was not with fabricators — work that was harder studio time — I had to get away. That was part of it. I actually had the idea to do those paintings and left so that I could do them.

It’s been a quarter of a century now that I’ve been here and things evolved over time. I went there and I built a studio that was designed so that it could be in Red Hook, Dresden or Santa Monica. Bali wasn’t important to what I was trying to do. I like working in shorts and I like being in the tropics and close to my natural, biological milieu, but I didn’t come here for Gauguinian reasons. I came here like some artists who need to get the hell out of New York so they move Upstate. I moved Upstate, but just further. It was really that logic. I didn’t have any interest in becoming one of those wispy characters that wash up on the beach with dreams of becoming one of these second-generation, third-rate Gauguins doing images of old ladies with really gnarly hands and local folklore or dogs of hideous pastel colors, I have no interest whatsoever. I wanted to do the work that I had planned to do, just in a setting that I was comfortable in.

Your 1996 painting Joan and the Cosmos is a realist portrayal of a woman in a Free Tibet T-shirt smoking a cigarette and taking a piss. Does she reflect your irreverence for political correctness?

That’s a good question. Oh gosh. I can’t decide if I’m politically correct or not. I’m somewhere in the middle. There are certain things I understand as being civic mindedness and decency and there are other things that are just ridiculous. Yeah, you’ve got to deflate things. I had a rule in that body of work. It had to be life-size and painted in the most non-painterly manner that I could come up with, which was like medical textbook illustration. The one overriding rule was could it actually happen? Farfetched as the situation might have been, they had to have been possible. They were both painstakingly in the style that I made them in and also that they were explicating the universes they inhabited and were making evident. Jerry Saltz had an interesting take on those, he said that I had managed to do with that body of work what I had done in my earlier pieces with logos, except rather than using the Judd box I had used a human form. I was actually a good point because that’s what I was trying to do.

Shortly afterward, you started making paintings with photographic elements layered into the process, such as in the 1998 painting of a non-conformist family The Vlaminkos. How do you play photography against painting?

It’s quite easy. That painting took me three full moons to complete. I thought there’s seriously something wrong here. Van Gogh can knock out a painting in a day — Picasso three in an afternoon. There’s something seriously wrong here. It wasn’t fun. That’s why after 10 years of making those kinds of paintings I eventually gave up. I’d sit for 16 hours a day, 6 days a week. All my friends who were surfing would say you’re a surfer and I’d say yeah, sometimes. They were so labor intensive. I did them in airbrush. The process got more complex as they went along. So much of my life has been spent trying to change the work to my actually biological framework and psychological framework more comfortably and suddenly I end up doing this form of advanced self-torture, falling into these traps. So to your question why put photographs in there? It saved a month of the painting. And considering the background that I had come out of sticking a photograph on there wasn’t a big deal. It’s all about language. I figured I had already spent three months making this painting so why not just take a photo rather than painting more details. Necessity is the mother of invention but it also opened up lots of other avenues.

The paintings that follow—at least in the show—seem to embrace island culture in a theatrical way. What brought about this dramatic shift in your work?

I said it earlier, but I’ll go back to it. When people keep saying you’re Neo Geo and you say your not until finally you just give up and say okay, “I’m Neo Geo, damn it, and I’m going to gave it to you in spades.” Well, that happened with the Gauguin kind of thing, because I had run off to an island. Not much lazy thinking will get you thinking oh, Gauguin, he ran off to an island, too. I wasn’t having anything to do with Gauguin. I had no particular interest. I had kind of liked him because I grew up in Hawaii and Polynesia. It kept coming up and I said you know what I’m going to give you Gauguin. So basically they were parodies. I just wanted to give it to you and then turn it in on itself—a sort of grand camp theater of a painting. I thought of them as inverse Allan McCollum surrogate paintings. Allan takes an artwork, a painting, a thing on the wall and dehydrates it like a bouillon cube and I want to rehydrate it to turn that process totally inside out. Instead of dehydrating it, I’m going to pump it up. You want sexuality, you want color, you want exoticism? I’m going to throw it at you like a monkey throwing feces. I was playing the Gauguin myth as a joke. I’d grown up in the tropics so I don’t have one gear for dealing with an artist who goes off to the tropics, but a lot of people do.

Is the 2007 painting Famili a real, fictional, or idyllic depiction of family life?

Famili came out of the idea of 19th century daguerreotype photography, where you pose and try to get all of the information about who you were in one shot. Because no one had cameras with them 24/7 taking a photograph was possibly a once in a lifetime thing, so you tried to get the entire meaning of your life into one picture. I decided to take that idea and turn it into an arch play of over-the-top camp again. All of the little bits and pieces—prolific fecundity with offspring, big fat joints, music, art, all kinds of absurdity, swords, martial skills, weaponry—it’s all a bit silly. I wanted to refer to sex and violence, to point in as many different directions as possible. It was a pretty simple premise.

The frame on this painting—and on others from this period—is amazingly ornate. What does the frame add to the story?

I guess I’ve always dealt with framing devices, but I was now dealing with things that were painting objects. Like I had done before, in the earlier works with logos, these were not meant to be paintings themselves, but parodies of what a painting is—just like my earlier works with the logos were parodies of what a painting was. The work in the ‘80s discussed itself in all of its different stations of existence. It discussed itself in storage; it discussed itself on the wall at the point of aesthetic reckoning; it discussed itself in reproduction; it discussed itself as an object of value that was traded; it discussed itself as a signature-bearing grand recognizable thing. That was what the purpose of those earlier objects was in the ‘80s. I tried to do that with these Gauguinish objects, with the over-the-top frames. People asked me what the frames meant. They meant absolutely nothing. They were just the volume turned up, like all of the different things I put into them. I think actually someone I spike to down here got it. He said all that bric-a-brac and tourist rubbish that you can buy—all the little coaster and bowls and things like that—you found a way to actually turn them into a true postmodern language. I thought okay you got it. I wasn’t interested in what those things meant. The carvings that were worked into those frames didn’t have any meaning. They were just noise. Oftentimes I tried to bring in totally irrelevant information that worked at cross-purposes with the piece because I never believed art should have one didactic reason for being. It’s not a thing that’s there to make a point, to elucidate an idea, to illustrate a thing. It’s a thing that can exist on multiple planes and be contradictory all at once. It’s thing unto itself.

Famili and the 2011 painting Red Scooter Nocturne have your Blue Man character playing a lead role. Am I wrong to see him as a possessed, wild, Beetlejuice-like figure?

He’s that, he’s…I don’t know. People say they see him as me, but I never saw him as me. Do I get some stuff from me? Sure, but I get stuff from Gauguin, from all of those archetypes—whether it be Graham Greene, whether it be Paul Bowles, or Paul Theroux or any number of characters. They are all male figures, if you notice, because he was constructed out of the Gauguin myth in Somerset Maugham’s Moon and Sixpence. I wanted a somewhat self-possessed, sort of expiring, sort of a lounge lizard transported to a tropical island with all the baggage of his ex-patria. Basically I saw him as an escape from 19th and 20th century literature—the classic anti-hero—but a comical character at the same time. I didn’t want him to be a hero in any sense. He’s clownish.

Your DNA paintings, of which there are two great examples in the show, make me think of the characters in the film Suicide Squad. What inspired them and what did the making of these types of paintings involve?

I think I saw Suicide Squad, but I can’t say I was very enamored by it. If my work goes in that direction at all it’s not because of that movie. There are certain things that I love—speaking of stylistic things like that, if you want to know the antecedents, the DNA, you have to go to films like Querelle by Fassbinder. There are certain stylistic things like the movie The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. These are the precedents. It doesn’t come out of Marvel Comics. Oftentimes each body of work starts with a silly, simple premise that’s based on an artist that I’m obsessed with. Like in my very early work it was a reaction to and built upon the back of Donald Judd. I thought advertising colonizes every desirable space and culture whether it’s the side of racecars or uniforms of soccer stars. Anything that’s desirable gets the fungus of logos, which catch hold. I thought what’s more exotic and glamorous and high-end and meaningful than art? So Donald Judd should have a Marlboro ad in the corner. That’s where those pieces came from. So starting with that reaction to an artist and building on the back off, that was Judd, and then later on Gauguin. And there was a time before that when I did a whole landscape series that was based on Kiefer’s landscapes. And then with these DNA heads, these large women’s heads, I was actually obsessed with DeKooning. So you want to base it on something like that, but let it have nothing to do with it and walk backwards and sweep up all of your footsteps to leave no trace—to steal something more intangible than the style or look of it, to go in and steal the motor, that’s somewhere in there. So the DNA pieces were based on DeKooning in some way. Basically, it was taking what I had learned from making the Blue Man paintings, where there was a mixture of painting, photography and sculpture, and trying to loosen the mediums up from each other. So that they could exist like they weren’t so blended. In Blue Man paintings I had been putting the meat and potatoes together into the blender and this time I was trying to separate them, but yet have them work together. I realized that instead of dripping paint all over my human models I could actually get rid of human models and just build them out of clay. Then they get more Cubist, because I don’t have real people and I don’t have to Cubify them in Photoshop. I can actually just make them that way when I’m constructing them. The less I try, the more Cubist they are. They’re like Mr. Potato Head. It was twofold in effort, one was intellectual—the one I just described—and the other one was really about trying to create a work that suited my temperamental needs—of getting bored real easily, never wanting to do those paintings that took three months and broke your back ever again, but wanting to do paintings that would take quite a few different activities to reach completion. I was thinking recently that as much as I like Clifford Still, if I had to do that work I would blow my brains out. I’ve had this idea for some time now—I hate uphill painting and I like downhill painting. It’s like in skiing you go up on the lift and ski down. You don’t have to walk up the hill. With a lot of painting you have to walk up the hill in order to come down. What I mean is that you stare at a big empty canvas and then you have to fill it up, laboriously bit by bit. When you get it all in and you have to play with the post-production kind of levers and finesse it and tune it and tweak it. That’s the part of the process that’s really fun and I thought why don’t I go straight to that part. Instead of having a blank canvas and filling it in mark by mark, why don’t I just go downhill for the fun part. That’s why I came up with the idea of getting to the top of the paintings—the hill—without anything being much of a complex, sustained effort. It’s like three or four fun different projects. In one I get to wear dirty clothes and cover myself in clay. We had already handmade all of the parts—the noses and ears and mouths—and I had tons of them in boxes. You sort of stick them in, work really fast and slop some paint around. Then you get to change your clothes and become a photographer and set up lighting and play with that and do all of these clever shots. Then you get to wear clean clothes again the next day and spend a couple days in Photoshop playing around with it, tearing it up and sticking it all together. Then you print it out big and then I have my team cut it all up—we could never print it all in one bit, because we don’t have printers big enough so we print it in parts and bits, which doesn’t really matter. Then you stick it together and mount it on a big piece of wood and then I come back to it again and throw paint all over it.

These DNA paintings deal with the grotesque in a way like Francis Picabia’s so-called “monster” paintings do. What’s your fascination with the grotesque?

It’s an odd thing. I’ve heard this before and can only go to the same defense—I thought they were cute. They were supposed to be beautiful. I never thought of them as the grotesque. They’re meant to be hot! I wanted to make nymphs, but I’m not actually talking about sex in my work—I’m talking about art. For me, it doesn’t matter if they are transvestites or transsexual cabaret performers. I don’t care. It’s a filter of femininity, as it is portrayed through the history of art. That’s what interests me. I’m doing them merely as types. It’s not that I want to do hot babes. History is rich with these characters. I do nymphs with a cold, jaundiced eye. But I thought they were kind of hot—or at least that’s what I was trying to do. They were supposed to be warm, winsome and alluring, but other people found them horrific and terrifying and witching and I’m like “Alright, I’m not the best judge of my own work.”

The most recent piece in the show, Wall-Wall SnS-S 2, takes your work full circle to your early work and these types of hybrid paintings. What made you come back to this body of work now?

Ok, I’ve got two answers for that. It was a very concerted effort and it took years to get here. At some point I realized that my career had become bifurcated, kind of disjointed in a way. I had people who think that I did some great stuff in the ‘80s and then I ran off to an island and just lost the plot. And then I have other people who know my newer work and then they come across my older work and go huh, that’s kind of boring. There are fortunately a few people that kind of get it all the way through. So what I wanted to do was to try to bring it round full circle—to find the overarching thematics, mechanisms, marked triggers and what have you to find out what my work was throughout. It was only when I was doing the recent show at Newport Street Gallery in London that Damien Hirst sent me a couple of earlier works that I completely forgotten about, some Wall-Wall works that he had and that had never been shown and were damaged. He said that he wanted to show them, could we fix them? He sent them to Bali and I started working on them and it turned out to be one of the most interesting things that I had ever faced. In a way, I had run away from my early work. This challenge came at a time when I was just ready to face it once again. When I started repairing them I learned two things right away. I wasn’t finished with this work at all. I had left it prematurely and there was still a hell of a lot more I could explore, that could be said with it. And the other thing was that you realize that you can’t take a coconut tree from a beach in Bali and plant it in New York City and you can’t take a sapling from Central Park and plant it in my garden. Things that grow organically here do not grow organically there and things that grow organically there do not grow organically here. To illustrate a point, whatever work I made in the ‘80s, that was organic, coming out of fabricators, industrial hardware stores, Canal Street, this and that. The things that I did 30 years later in Bali with the giant frames that came organically out of here, that’s what grows. So when I tried to remake the work that I’d made in New York all those years ago here, I found out nothing fit. I was just fighting uphill on a slippery surface. There was no traction. It was a joke. It’s been kind of a nightmare. I’ve been really struggling, but I’m finally getting there.

October 24, 2017