Wilfried Lentz: art fairs are not a condition for growth (an interview)

Rotterdam-based gallerist Wilfried Lentz shares his thoughts on the art business and his successful focus on gallery programmes.

When it comes to buying contemporary art, Rotterdam is probably not among the first destinations in the European landscape collectors would pick up for their shopping. Yet Wilfried Lentz Rotterdam is a little gallery gem. Starting from the architecture (the bathhouse of 1920s housing complex) and continuing to its excellent international program of emerging artists, the gallery has a museum flavour to it. We speculate that these exceptional characteristics are the result of a special care Wilfried Lentz gives to the gallery itself as opposed to considering the space as a mere accessory to dealing art at fairs or online. And while this attitude has proven very effective in terms of quality of art on display, we learn that contrary to many trends in today’s art market, a focus on the gallery and its program has been economically successful too.

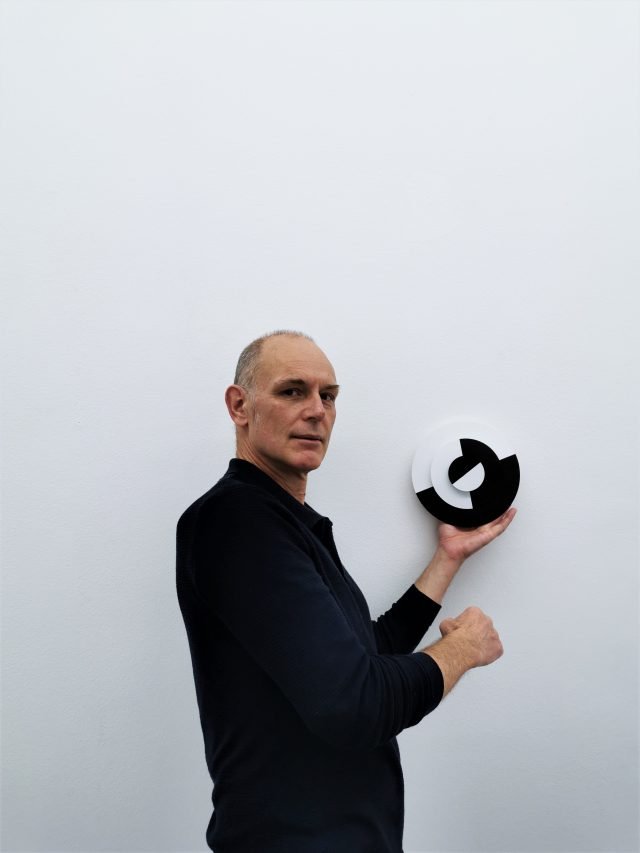

Wilfried Lentz, Milano, 2019. Ph. Stefano Pirovano.

Starting with your background, we read that from 2000 till 2008 you were part of the national committee for public art in the Netherlands. Could you talk a little bit about that experience?

Wilfried Lentz: It was an advisory role for municipalities across the country, some of which were more in need of such consultancy from our side. If there was a project of placing an artwork in a certain spot, we would make sure the art was relevant. Instead of thinking right away about the physical and visual solution, we would first try to find an interesting subject or concept related to the commission, also linked to what was going in the arts in general at that time. For example, even though we were not directly involved in that decision, the sculpture by Paul McCarthy in Rotterdam [Santa Claus with a butt plug] is a good example, as it was chosen to be a symbol of hidden desires, a topic that was thought to be interesting in connection with consumerism and the shopping area in which the sculpture is placed. Examples like this are still important for me as a gallerist, since they point to thinking about art also in terms of content instead of solely look.

How did you go from being part of that committee to becoming a gallerist?

Wilfried Lentz: I have always wanted to open a beautiful little shop selling the most beautiful things in the world, a very romantic idea. My father was pastry baker and also had a shop, and I also wanted to be an entrepreneur to sell beautiful things.

Your gallery program has also included videos. What’s like to sell videos? Do you think the market of video art should be closer to that of films, with less scarcity of access to the works and systems such as renting online to watch them?

Wilfried Lentz: In the visual arts, and especially video, the setting is in a gallery or museum, relatively small production budgets and a small potential of financing through sales of the video work to collections. Cinema is another kind of experience. In the cinema industry, there are huge production budgets, potentially high paybacks through ticket sales. Because a film production is often very costly, there is another tradition of production and distribution. Video art is cheaper to make and production costs can sometimes be almost irrelevant. Moreover and more importantly, it is the artist that often wants their work to be experienced differently than film in a cinema. I really think it is about what the artist wants, not what the market wants. If the artist wants to make a film that involves a bigger production, they could go for film-like distribution but it’s their choice.

This choice often means that fewer people get to see these videos.

Wilfried Lentz: That’s true, but this might still be what the artist wants.

Some commentators think that a contemporary art gallery today needs to grow considerably in order to remain in business. Often, a necessary condition to grow for galleries is being involved in the circuit of art fairs, though in a previous interview you seem quite skeptical of art fairs. I wonder if there is a way for galleries to grow considerably without participating to fairs. What do you think?

Wilfried Lentz: For big galleries, it is easier to go for art fairs, as the cost of participation is really large. For galleries like mine focusing on emerging artists, their market doesn’t make it possible to participate to big fairs. I stopped participating to many big fairs 4-5 years ago, since it was too hard and costly to maintain a proper program at the gallery and going to these fairs too. My way has really been to concentrate on the gallery program and distributing the work through the gallery instead of the fair. I now have fewer costs and more time to take care of the program properly. Gallerists from my generation who have decided to do more than 6 fairs a year have had to present art that is more easily sellable just in order to cover the costs, which might mean compromising on your program. What I see is that many of these galleries are struggling, because they have to keep their physical expensive space anyway. Many of them, especially those based in expensive places like Chelsea or London, just went broke. For me, the decision of dropping many fairs has proven successful, and the last years have been my best years economically speaking. I’m an example of the fact the fairs are not a necessary condition for growth. There are of course those galleries that have a very commercial program, and fairs are a good choice for them. I respect that decision, as that’s their choice of business.

But to be clear, I’m not against fairs, it’s a necessary distribution model in the art business. At the moment there are just too many. You also need to be aware that they are primarily places for commerce. What might happen in fairs is that something in the experience of the artwork is lost, and it is important that those who are there to sell as well as to buy are aware of this problem. On the other hand, what you get in fairs is that some work is designed just to induce fast emotions, what we in Holland call “noble kitsch”. Collectors can get confused in fairs, and they should know that this risk is there. In this sense, any collateral event that’s attached to art fairs like curated exhibitions just add to this possible confusion. Ultimately, what I think could be a good innovation in terms of art fairs is specialisation (like LOOP). Art fairs today look too much like one another and even some boutique fairs I have recently participated to such as Independent in Brussels and Granpalazzo in Rome were not specialised enough. What I liked about these at least was that the cost was comparatively low (which meant the possibility to experiment) and that the location was quite specific.

You market is both international and local. Talking about the latter, would you say art collectors in Rotterdam have some distinguishing traits?

Wilfried Lentz: No, they are like other collectors everywhere. There is not a Rotterdam breed of collectors.

One of the artists you represent, Giorgio Andreotta Calò, was part of the Italian pavilion at the Venice Biennale this year. Did you contribute to the production of his participation and what are the benefits for a gallery to invest in the production of large events such as Biennials?

Wilfried Lentz: There was a substantial investment in the production of the whole installation by acquiring sculptural works Giorgio made for that pavilion. I would say that this type of investment is not without risk, though there is a benefit for both the gallery and the artist on the long run. At such a platform, as a gallerist you should do everything possible to make the highest quality possible and increase the reputation of your artists and better their career. This is more a question of responsibility towards your artists that the economic benefits you might get from the investment. I understand it looks very beneficial to invest in such way from the outside, that the gallerist has a huge benefit from these investments, that the gallerist makes a big sale after the biennial. The opposite is true. In the case of Giorgio for example, it is not the case that he’s producing a lot for the market. His main concern is to make the best art possible according to his wants. Of course, a balance between completely following what you want to do as an artist and keeping a market for you work needs to be found.

In the last question, I would like to link our discussion to a provocative article that just came out on the New Yorker about the big sales of Damien Hirst’s Venetian show and the art business in general. In the article the writer paints a rather negative picture of gallerists. To quote: “galleries sell their artists’ works at below-market prices, thereby allowing their collectors to feel that they’ve made a profit on every purchase” and “the entire gallery system is based on the idea that all art works have a secondary-market value” and “even the most highbrow and cerebral gallerists are forced to play this game”. Do you care to comment from your point of view?

Wilfried Lentz: For me it’s really more about production and distribution than about selling, which are different things. What media does is to confirm the idea that art is a commodity, and this seems also the assumption in the article. Of course there are dealers that treat art only as a commodity, but you can also see art as an experience. In this case, you never use the argument of the increased value or the one of the secondary market. I don’t know which gallerists the author of the article has in mind, his view is too generic. For example, you also have galleries that show art that doesn’t have a market, therefore they take the risk investing in what might never yield a return. Imagine if there were no such galleries, who would show emerging artists? Definitely not the art advisors or auction houses, and public funding is too limited even in the Netherlands [where public funding for visual art is big]. If you take all the shows in one year and remove those at galleries, I take it that there would be at least 50% fewer shows. Can we talk about art now?

December 3, 2019