Revelation Theater

Antoine Levi, Paris

Srijon Chowdhury

20 September – 19 October 2019

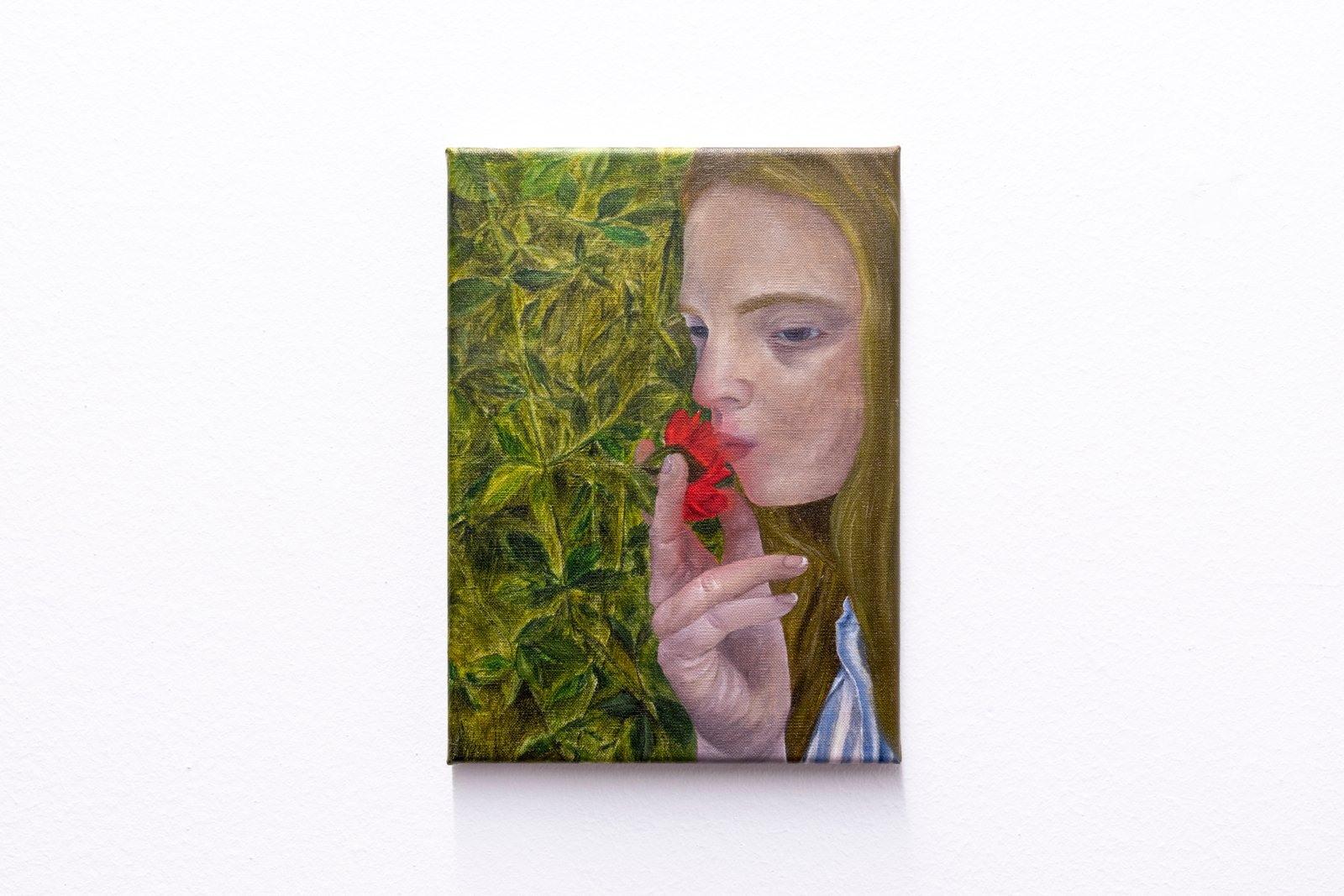

Hiding

To attain intimacy with death: could such a thing be possible? To live closely with the most strange of all strangers… –Yet: not so that one can ever-draw-near to death and come to gain knowledge of what necessarily outstrips the nature of mortality; but instead, to become intimate in order to preserve death as the question that it is, to know death as always at a distance away, that is, in its strange inaccessibility—in the way it saturates every moment, imperceptibly—so inaccessible that the mere word, “death,” suffices entirely. To attain an intimacy with death: to enter into an intense proximity with the stranger, yet, because one is always without right or warrant, one is unable to say, “I know death.” Could such intimacy be possible?

With the skill of a poet, Srijon Chowdhury has buried this question within his 2018 Revelation Theater.

Chowdhury’s method for producing Revelation Theater gives clear priority to patience. His attention to detail, the amount of imagery (both subtle and spectacular) that he is able to fit within each frame, and the density of information that he manages to bring together all bear witness to this fact. Importantly, the line of questioning that his work makes possible, i.e., the question of an intimacy with death, must be approached with the same diligent patience. In Revelation Theater, the question of intimacy with death—just like all the detail, imagery, and information in the work—presents itself in the form of an ambiguity. Exposing at once, the polarities: curiosity and unease; hope and dread; etc. What is more, for Chowdhury, the points of ambiguity do not represent a moment of contrast. That is, his is not a battle of hope or dread, curiosity or unease. Rather, the phenomenon that he captures is the overriding power of the indistinguishable. The hope is located in the image of dread, the dread, within hope. Dead figures, hands offering gestures of significance, utopic visions of life, and glimmers, sparkles of light shrouded in the darkness they presuppose. Does not a room full of darkness already represent the content of the room, now well lit?

It is here, in the face of indistinguishability, where the question of the possibility of attaining an intimacy with death initially crops up in Chowdhury’s work. To know death as nothing other than what, in the mundane rehearsal of one’s daily habits, animates the necessary backdrop of one’s life…of one’s capacity for living in general. Becoming-intimate with that which is eternally here but never present—death obscures life, rendering it simultaneously wide-open and cordoned off. Chowdhury’s Revelation Theater focuses acutely on the impossibility of finding satisfaction in life without also paying heed to the weight of sorrow it carries on its back.

As Giorgio Agamben once observed, “light is only the coming to itself of the dark.”

Glory

The last words of the great mystic, Catherine of Siena, are as distinct as they are astonishing. She entered into God’s glory with a final cry, “Blood! Blood!”

In the first painting that presents itself, the spirits dance.

With a complete oversaturation of the fauvist palette, Chowdhury’s dancers have been driven to a point of excess. Yet, somehow the rhythm of the movement is retained: Chowdhury transforms Matisse’s dancing nudes, along with their sensuous, animal-like hedonism, into an image of the perversity of spiritual ecstasy. We are told in Genesis 3:17: “And the eyes of both were opened, and they knew they were naked.” Fallen from grace, Adam and Eve clothed themselves. Their newfound ability to perceive each other’s body as a naked object is a testament to their sin. Covering oneself, getting dressed, is an act that paradoxically reveals precisely what it covers over: the potentiality to be naked, to exist in a state of undisturbed grace.

For Chowdhury, one must be ever ready to admit that spiritual existence is something quite different from what it is typically taken to be. As Simone Weil, a mystic closer to our own time, put it, “every being cries out silently to be read differently.” Chowdhury insists on reading-differently the supposed purity found in spiritual being. His dancers remain covered in the fire and the blood—maniacally struggling to revel in their bare exposure—lest they obtain the grace that is, for them, inaccessible. Their nudity is covered over, not by the well-defined vines, flowers, and fruit, but by their very being. The spirit lives in a state of unclothed grace, but dwells apart from the reality, the body, in which grace obtains. Their nudity has been stripped by the fire, and been covered by the blood, of red; their flesh has fallen away. For them, nudity is not an optional condition. It simply is: being. But the nudity of the spirit is wholly unlike the nudity of body. Blood! Blood! Or again, as Weil wrote, “I should not love my suffering because it is useful. I should love it because it is.” Not marked by lightness, freedom, or flight, the spirit’s nudity is a laceration, a point of perverse agony wherein redemption and damnation cannot be held apart.

…To read the spirit as it is certainly something different, possibly something utterly different, from what we read it to be.

Forfeiture

But then again, reading is only one of a hundred ways of gaining access to something. Reading, no doubt, is a mode of access to the surface of something (e.g., a text, an image, an activity, etc.). But what is it to have a sense of the meaning of a work of art, a painting? Perhaps it involves not just the ability to read—or even the power to interpret or criticize the work—but also the capacity to lose touch with one’s skill of reading. In other words, perhaps gaining a sense of Chowdhury’s work involves the ability to forget, delivering one’s ability to make judgments (e.g., about this or that, or about whether such and such is the case) to the unconscious.

As in a dream, a green woman rides a green horse.

Walter Benjamin saw well the connection between forgetfulness and the unconscious. “The unconscious—which has the power to turn impressions and images, however fleeting, into extracts we often recognize in dreams.” It is thus no surprise that understanding the meaning of a work of art often involves submitting to a waking dream about an image, or figure, or the density of color, even before one comes to know the work at all. Engulfing the viewer, Revelation Theater is Chowdhury’s invitation to disremember, at least for a moment, how to read, and to instead struggle to make sense of the fragments of that which can never be caught but only be forgotten. …And then there is an image of the naked figure in repose, Narcissus by the stream. Caught in reverie, the figure finds their reflection, the immediate content that is being read, to be like a mask, like something unfamiliar. The movement of losing oneself in the reflection of oneself, of consigning one’s ability to read to one’s unconscious—which is it: a taking-leave-from the animal kingdom, or a trying-to-gain-access?

An interesting aspect of forgetfulness is the way it renders impossible to discern between moments of opposition. Thoughts align differently, and compose themselves in otherwise unfamiliar ways. The dying Messiah and the Tyrant. The two have, in the course of history, too often confused themselves with one another. Like Chowdhury’s image of hope: the suicide gun, enveloping the bouquet veiled in darkness, the breaking of light always already presumed. To think hope as death, as Walter Benjamin did, on the night he took his life at the closed border of Spain, fleeing occupied France. “In a situation presenting no way out, I have no other choice but to make an end of it.” Tarrying with death—just one night before the Spanish border was reopened—he found the safe harbor that had evaded him on earth.

In Revelation Theater taking-leave and entering-in are one and the same.