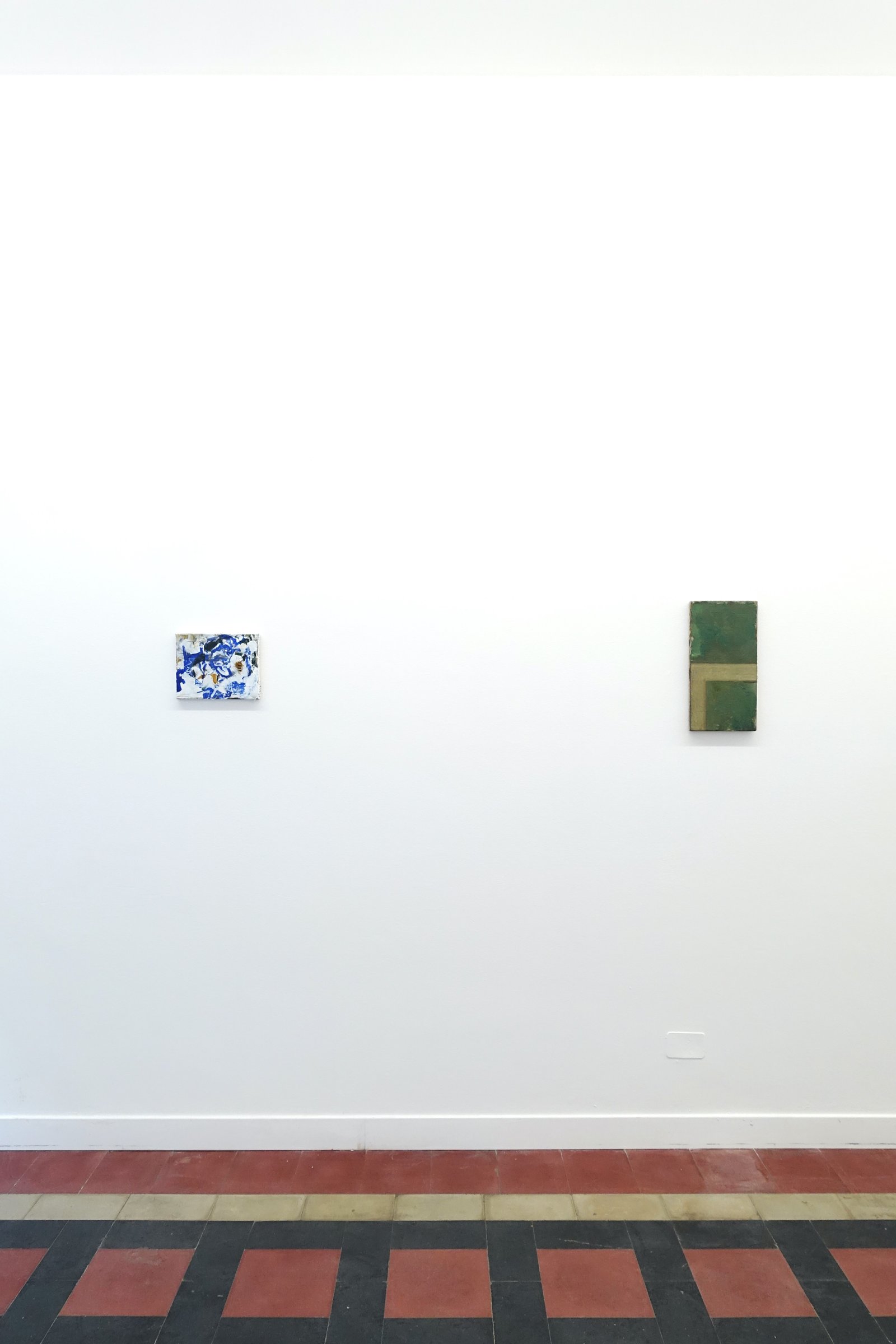

Seeds, Voids and Tailor Cloths

Claas Reiss, London

Daniel Graham Loxton, Matthew Peers, Jens Fröberg

27 October – 10 December 2022

The pieces on show are somewhat small, scruffy even. The American Daniel Graham Loxton, the British Matthew Peers, and the Swedish Jens Fröberg, three artists assembled by the London based gallerist Claas Reiss for his gallery residency at CFA in via rossini 3, bring to Milan an exhibition of vies minuscules and material events; its title: Seeds, Voids, and Tailored Cloth. I’ll begin by describing what I see and feel in front of past and recent works by each of the three artists, analysing them individually, and casting distinct feelings.

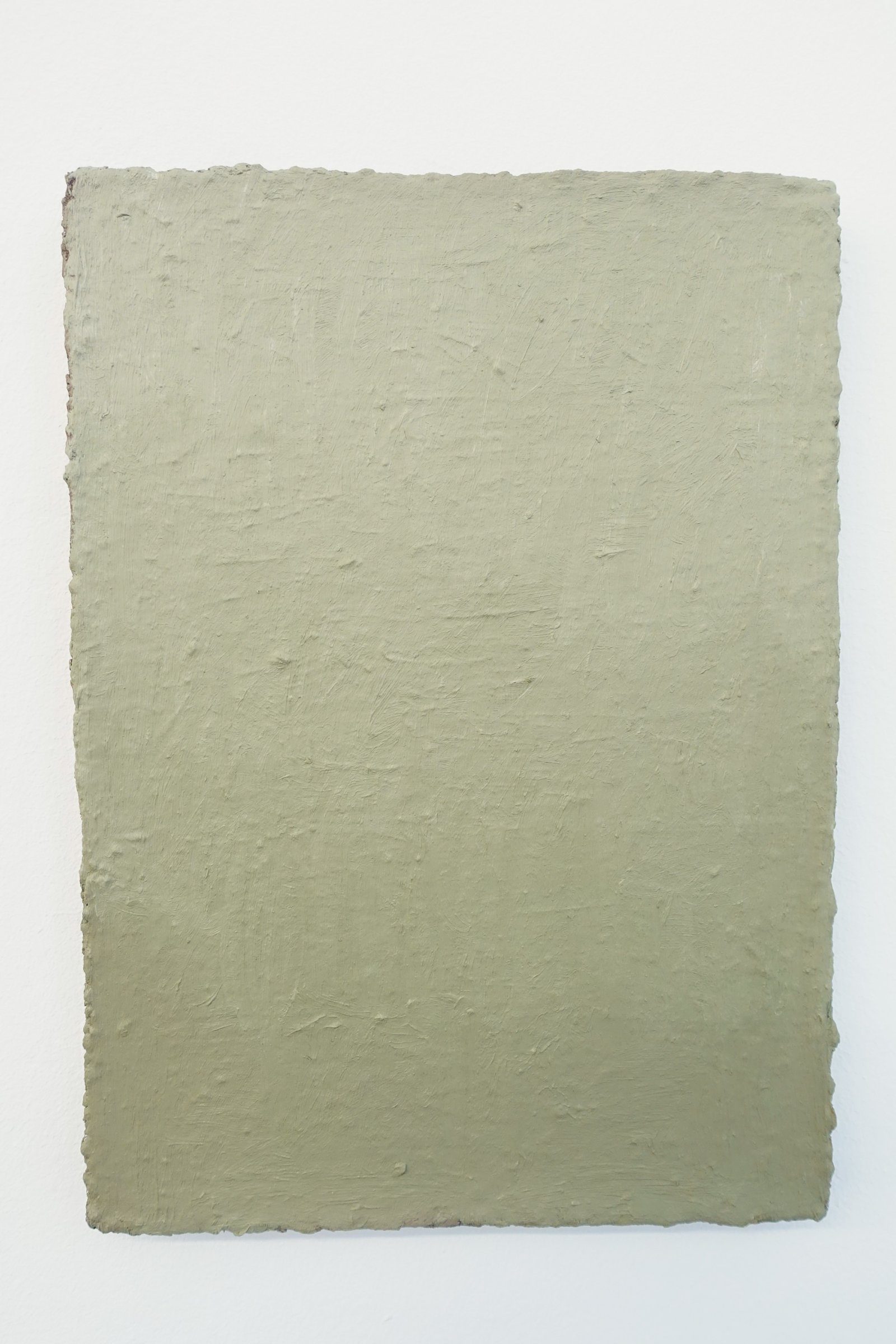

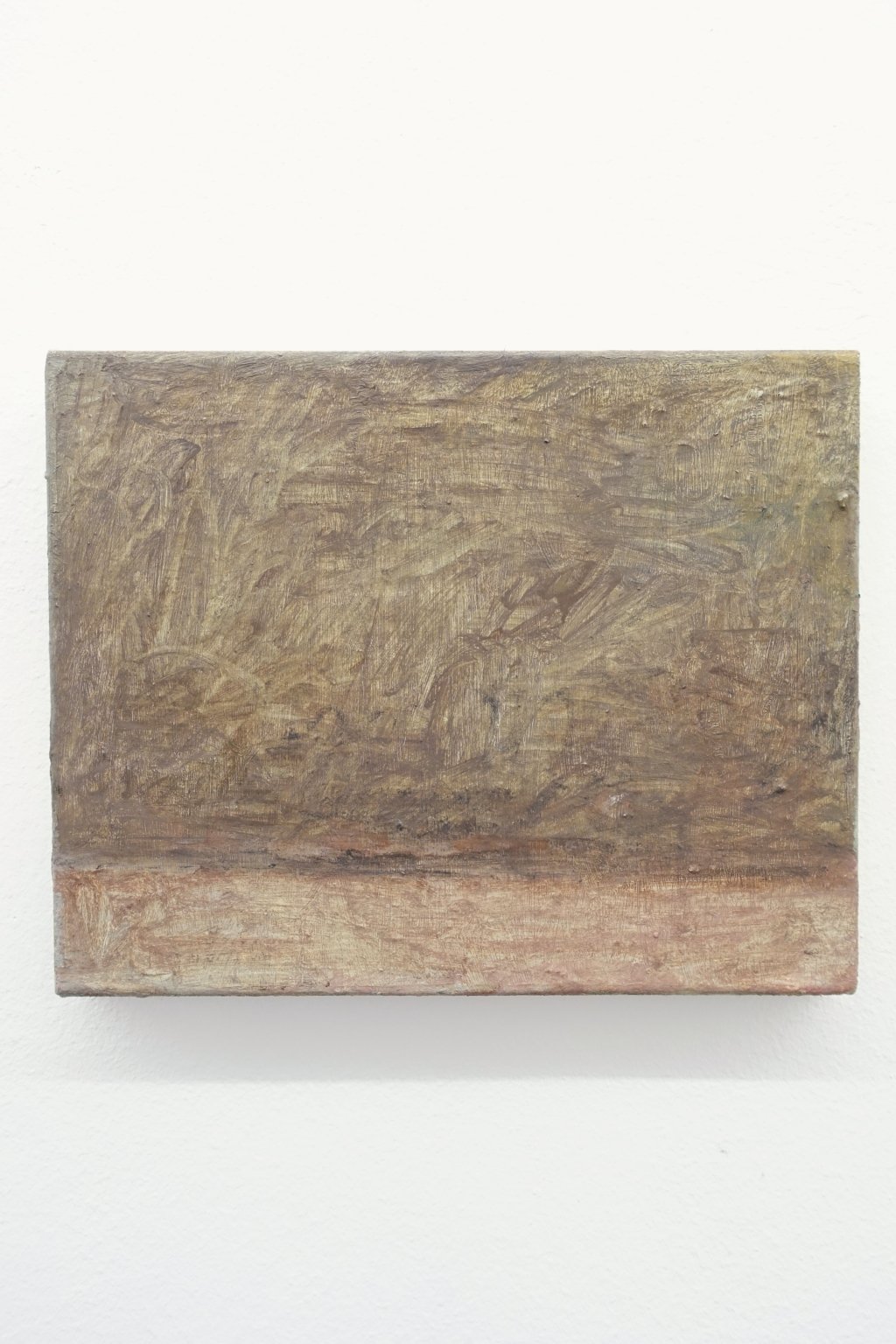

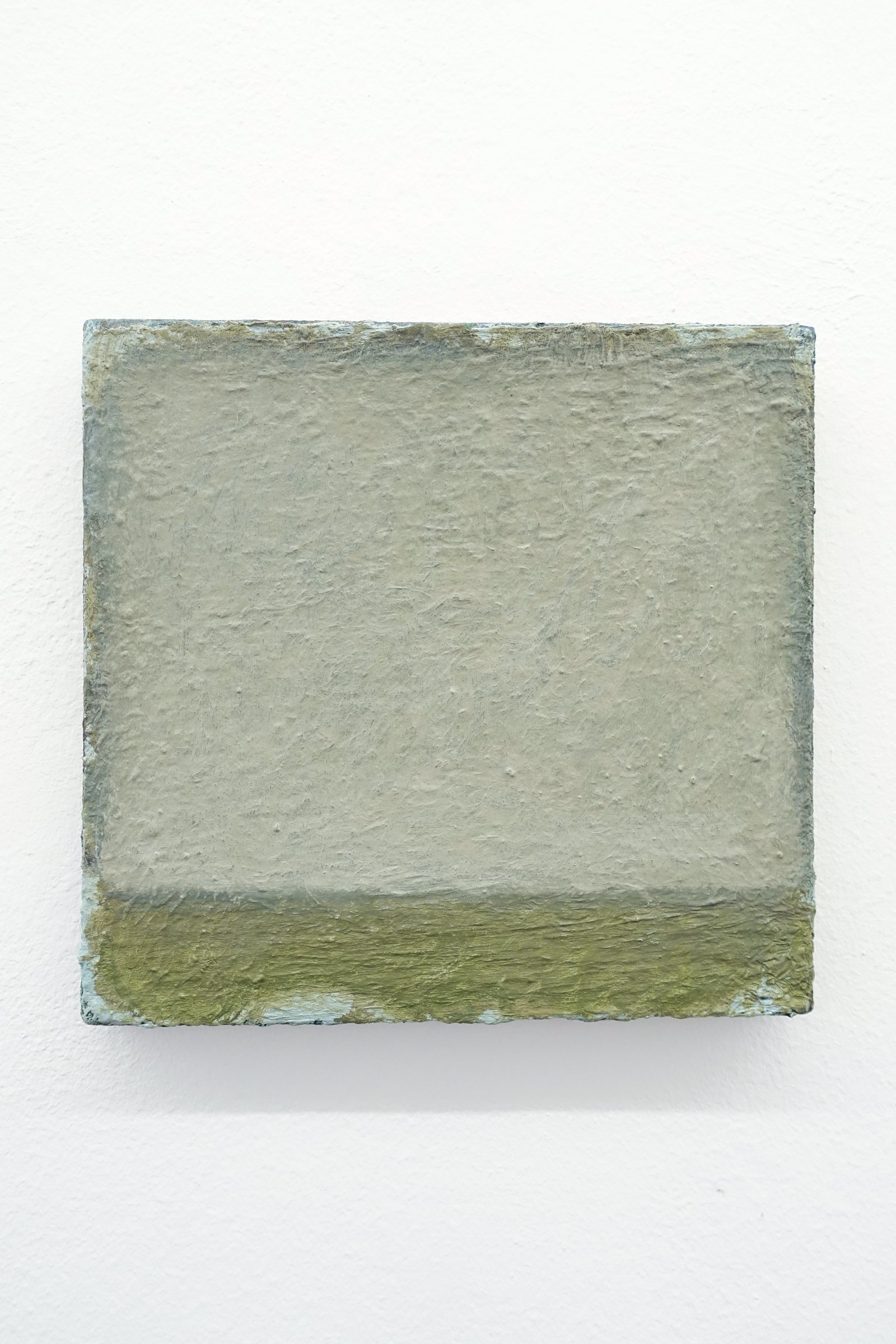

Looking at Jens’s works

The underlying frame appears from the frayed edge of a canvas. As a broken wave, the grey-green badly covers the olive green. On another surface, convulsive and translucent brushstrokes seem to paint a romantic sky, yet they are centripetal, closed, and filling. Three areas of colours taken from Chardin stand silently on a small canvas; they cancel each other out, creating no spatiality, catching the last rays of a milky star. Elsewhere, a rectangle holds a white square, projecting a rosy shadow that evokes Morandi’s meridian stillness and the starched fabric covering a liturgical chalice. Wherever you look, the image is trapped in heavy layers of matter, emphasising its immanence and finitude. Jens says: ‘Ideas come to me while seeing, reading and thinking about art. The works deal with art movements such as minimalism and colour field painting, and occasionally refer to more specific works; the compositions are often alterations of things I have seen. It can be details from film scenes, artworks, architecture, or nature. In a sense this is research, although it’s not actively searched for, but rather it arises by itself.’ The emerging slowness of the image is silent, heavy; it finds its semantic contours at the last minute, just before Jens cleans the brush.

Looking at Daniel’s work

I gaze across a painting divided into three imperceptible areas, flecked with colours that evoke a landscape, or perhaps a topographical design. Certain areas are lyrical, others graphic. My mind sweeps through distant views: the implosion of Graham Sutherland; or the explosion of Carol Rhodes. In another painting, some parallel, flexed signs evoke blades of grass, traced like calligraphic gestures. They are painted on a convulsive white background reminiscent of stucco festoons. Elsewhere, layers of corrugated cardboard and discarded leather are glued on the canvas. Daniel doesn’t try to limit or censor his penchant for meta-painting. He told me we had a mutual friend, the painter Lawrence Carroll, and that he read a past text of mine in which I wrote that Lawrence was more fond of the paint-stained materials scattered around the studio than the canvas itself. Perhaps it also applies to Daniel. Other artists, like Walter Swennen and Jef Geys come to mind, but Daniel does not do painting about painting; he paints as if he were holding a notebook of painter’s notes on painting–the works themselves becoming notebooks in a continuum – an edition within a massive library. The writer, Slavist and horticulturist Pia Pera wrote: ‘A garden might be like a canvas on which to paint, but a kitchen garden is like a folio divided into four sections, themselves divided into four parts that are soon thought of as pages with rows, lines, syntax, punctuation, and paragraphs.’ The Hortus is fenced–Daniel’s paintings are also kitchen gardens: luxuriant pages of enclosed annotations. Daniel says: ‘I tend to work in constellations as opposed to series–a constellation being a group of works without a common impetus and having a vantage point that is unfixed. Often, only in hindsight, even for me, does the image of the constellation emerge. I prefer the scope of my work to bleed out over the edges of the gallery walls and into future and past bodies of work, as if one could zoom out far enough someday to see the contours of a larger cerebral space in which all of my works exist.’.

Looking at Matthew’s works

Matthew’s works remind me of those by Melotti in the early 1960s, the years of Il Canal Grande (1963), or the small architectures by the ceramist Franz Josef Altenburg. He scales dwellings down, evoking a sense of intimacy and domesticity, even of limitations. Getting acquainted with his art, I linger at his three-dimensional pieces, which trade the materiality of worn-out cardboard for sand cast aluminium. Matthew says: ‘The ongoing series of works holes uses found cardboard as a starting point. This ‘poor’ material has already had a life, a use value. A history of travel, distribution, of being handled, held, touched and marked.’ holes: are they boxes, theatres without a show, cages, intersecting planes of a painting or a sculpture? I am reminded of Joseph Cornell and his carillon-box Shoot the Chutes (1941), where the circular openings suggest the eyepiece of a telescope, or the mirror of a kaleidoscope with the related chain of visual stories articulated in the entrelacement. With Cornell, every opening implies concealment, a look into multiple peepholes, a creator of rebus. Matthew sidesteps the narrative: The circular shape is a simple hole, an opening that allows you to visually penetrate the surfaces of the composition. The play of holes on painted surfaces enhances the three-dimensionality. ‘The joy of putting things together, matter that touches matter, matter that touches thought, thought that touches thought, thought that touches matter,’ writes Matthew. Each work is a visual and material transcription of a ‘doing’ whose meaning is almost tautological: the action itself of doing, which has a duration and is influenced by a feeling arisen from a collaboration with a craftsman– ‘to do’, a verb that is also a segment of life. As if they were fossils of what is lost, the pieces track down the material on the way it was experienced and altered by the artist, as if it was part of the Chinese Tangram puzzles.

Grouped together

The three artists together present an exhibition that deals with the various stages of reification of the image: the material immanent in the image (Jens), that which is assembled into the work as ready-made (Daniel), and that which is transfigured from one material to another (Matthew). The protagonist of this translation is not an object of mass consumption, nor an idol, as in the kind of contemporary art we are more and more accustomed to; it is, rather, a scrap of cloth, a piece of cardboard, a small thing. The materiality of the cardboard is especially present; appreciated by both Daniel and Matthew, it is a symbol of protection, but in the current world of home delivery, it also stands for facilitation, globalisation, and travel. On the other hand, Jens and Daniel join in making art that originates from art. When compared to the choice of using newspaper mounted on linen canvas, Daniel refers to the invention of this technique by the New York School: ‘Simply put, I’m a New York painter, why not start where they did?’ This ‘they’, which evokes the phantasmic and phantasmagoric presence of the painters who preceded the present discourse, is relevant insofar as it implies a dialogue. Painting is often mistakenly considered the most solitary of the artistic mediums; it is a constant dialogue instead. There is no painting without a dialectic between one painter and another, contemporary or not. Painting is a group sport. Moreover, the importance of the process with respect to the outcome is a non-negligible feature uniting these artists. Jens says he experiences a state that is both ‘frustrating and exciting’ while painting. ‘It is never a painful process. I don’t agonise over them, even the ones that take a long time’ says Daniel about his works. For Matthew, the process begins at the train station, even before entering the foundry: ‘I work with non art based technicians in a small commercial foundry in west Sussex. I see this social and democratic dialogue as part of the sculptural act, along with the walk to and from the train station to the foundry. The final sculpture is embodied with collaboration, the distance traveled and the thoughts and feelings that have been had along the way.’ As if trying to solve a difficult but compelling puzzle, the three artists study the possibilities inherent in images, poor and worn out materials, continuing the imperishable game of walking the paths – those that are less glossy and richer in weeds – of visual language.’

Sofia Silva, October 2022. Silva is a Padua, Italy based artist and writer.