Top Italian art collection is looking for a place

Collezione Giovanardi’s hires are seeking a new art institution to preserve Augusto Giovanardi’s pivotal legacy. Who will be the lucky one?

- Palazzo Fava. Bologna, Costruire il Novecento, capolavori della Collezione Giovanardi. Photographer Paolo Righi/Meridiana Immagini.

- Palazzo Fava. Bologna, Costruire il Novecento, capolavori della Collezione Giovanardi. Photographer Paolo Righi/Meridiana Immagini.

- Carlo Carrà, Marina con albero, 1930. Courtesy of Collezione Giovanardi.

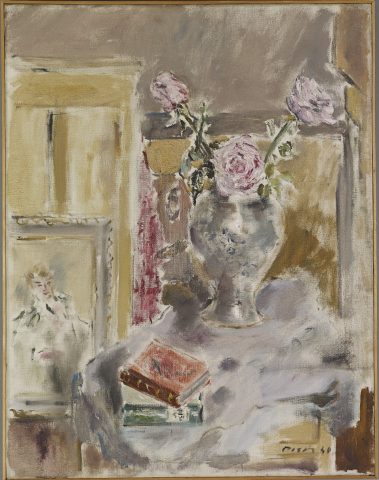

- Filippo De Pisis, Interno con rose, 1940. Courtesy of Collezione Giovanardi.

- Mario Mafai, Demolizione all’Augusteo, 1936. Courtesy of Collezione Giovanardi.

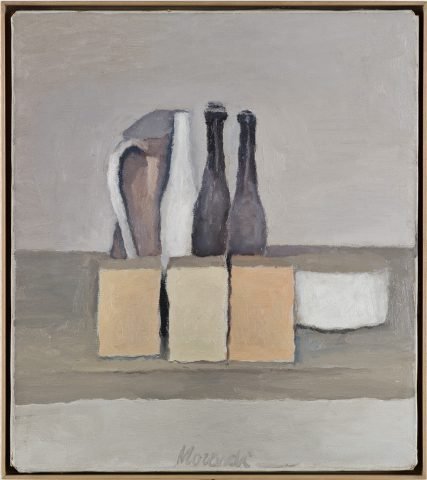

- Giorgio Morandi, Natura morta, 1956. Courtesy of Collezione Giovanardi.

Every expert in European art from the last century will agree that the collection of Italian paintings built by Augusto Giovanardi and his wife Francesca Marzoli between 1947 and the late 1980s is a fundamental piece of Western art history, particularly with regards to artists such as Mario Sironi, Carlo Carrà, Filippo De Pisis, Osvaldo Licini and Giorgio Morandi. And these same experts, along with some maverick collector, are probably wondering what will happen to this unique body of 90 masterpieces now that the comprehensive exhibition dedicated to it by the city of Bologna at Palazzo Fava is over (Costruire in Novecento, capolavori della Collezione Giovanardi). ‘We are assessing how to proceed’ told a few days ago Luisa Cristiana Curti to CFA , ‘if we can’t find a public institution meeting the needs of the collection, we will take care of it ourselves”.

Ms. Curti is Augusto Giovanardi’s niece. She is the daughter of Marta Giovanardi, who prematurely died in 1998, just a year after she inherited the whole collection along with her elder sister, Paola Giovanardi Rossi. This latter and Ms. Curti are now the owners of the collection and are legally responsible for its good preservation. The whole collection is in fact officially protected by the Italian government, which ‘notified’ it in 1998 under specific request of Marta and Paola Giovanardi. It means that the Collezione Giovanardi can’t leave Italy, except for temporary exhibitions, and owners cannot divide it by selling any of the artworks.

From 1997 to 2015 the collection had been in deposit at the MART museum in Rovereto, under the direction of Gabriella Belli, now director of the Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia. During this period the museum paid a fee to Paola Giovanardi Rossi and Cristiana Curti and took the responsibility of preserving and exhibiting the collection, that has been the museum’s crown jewel so far. But in 2015, due to a questionable change of strategy, the current museum director, Gianfranco Maraniello, decided to cut the fee and give the collection back to the owners.

Augusto Giovanardi was not only a distinguished scientist and university professor who played a pivotal role in the creation of the Italian national health system. He was also a master collector of contemporary art, devoted to quality and aware of the cultural values he was promoting by collecting art. He started buying young artists in 1949, when in order to feed his new passion he sold his collection of painting from the XVIII century. He was 45 at that time, and the first painting he bought was by Arturo Tosi, an artist he felt consistent with the kind of art he had been collecting until then – later he understood he wasn’t so. Soon he became client of the main contemporary art dealers in Milan, where he moved with his family in 1947. These early gallerists were Gino and Peppino Ghirighelli (Il Milione), Carlo Cardazzo (Il Naviglio), Bruno Grossetti (L’Annunciata), Ettore Gianferrari and Claudia, his daughter. ‘He was the kind of collector – says Cristiana Curti – who run to the train station to be the first one meeting Gino Ghirighelli arriving from Bologna with new paintings by Giorgio Morandi, for he wanted to buy the best pieces’. He was used to take two or three paintings each time, and bring them home. It took a few days to chose which one he would then acquire. But dealers knew he often bought all of them. ‘But my grandfather – says Ms Curti – was always ready to sell or swap works if that meant improving the quality of his collection. By the end of the Eighties, when he stopped buying, it included 14 pieces by Osvaldo Licini, 8 outstanding Filippo De Pisis, 8 Mario Sironi and 21 selected paintings by Giorgio Morandi, currently the artist’s main body of works available in a single collection.

Today many art professionals, and probably not only them, may argue that the private property of such an unique treasure is de facto limited by the Italian exportation law, and would disapprove Augusto’s heirs’ decision to spontaneously ask for their father’s collection to be ‘notified’ by the Italian authorities. And considering how it affects the economic value of each work in the collection they are probably right. But on the other hand the so called ‘notifica’ is also protecting against auction houses the extraordinary job made by Giovanardi during his life. In this regard, it is worth recalling that just a few months ago Sotheby’s liquidated, and forever dismembered, the extraordinary art collection of Alfred Taubman. In that case no one noticed the fact that very few people in history have been in a better position than Taubman for buying art. Sotheby’s, which operated this historical sale, lost its bet, for the guarantee it paid to the Taubman’s heirs for winning the consignment exceeded the sale total giving a very bad message to the market: why should I invest in art if even the collection of Alfred Taubman, rich businessman and former chairman at Sotheby’s, fail in making profits? In the instance of Collezione Givanardi the message is no market oriented, but somehow more positive and effective even without that high impact communication weapon that the bid price is: quality is always a better measure of intelligence than money.

December 15, 2017