Anna Conway and how to switch on the painting’s inner light

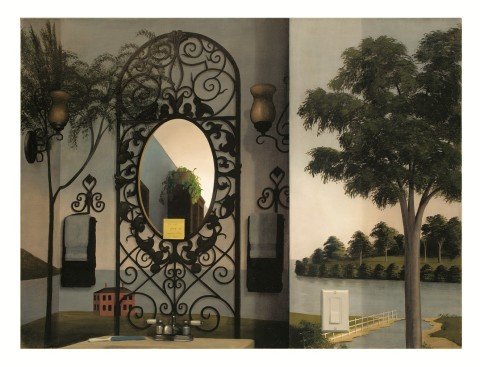

- Anna Conway, Somebody call someone, 2004; oil on panel, 42.5″ x 78″. © Anna Conway.

- Anna Conway, Somebody call someone, detail. © Anna Conway.

- Anna Conway, Purpose, exhibition view at Collezione Maramotti, Reggio Emilia. Ph. Carlo Vannini.

- Anna Conway, It’s not going to happen like that, 2013; oil on linen 76,2 x 101,6 cm. Courtesy Collezione Maramotti © Anna Conway.

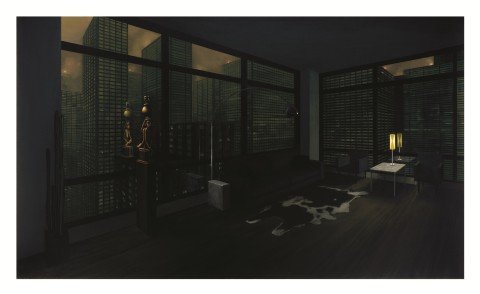

- Anna Conway, Determination, 2015; oil on linen 71,1 x 121,9 cm. Courtesy Collezione Maramotti © Anna Conway.

- Anna Conway, Perseverance, 2015; oil on panel 76,2 x 121,9 cm. Courtesy Collezione Maramotti © Anna Conway.

- Anna Conway, Potential, 2015; oil on linen 132,8 x 203,2 cm. Courtesy Collaramotti © Anna Conway.

- Anna Conway, Devotion, 2015; oil on linen 111,8 x 182,9 cm. Courtesy Collezione Maramotti © Anna Conway.

Our entry question for Anna Conway is about the weather. We are talking with her via Skype, in occasion of “Purpose”, her current thoughtful solo show at Collezione Maramotti in Reggio Emilia. We choose to start with this neutral topic in order to kindly break the ice with her. But Conway’s answer is far from being an easy one. Instead of saying whether the sky is sunny or cloudy, she tells us the exact temperature and complains about the uncomfortable difference between the Fahrenheit and Celsius scale: “It is crazy – she says – that we still have such useless differences, isn’t it? I have just come back from Italy. While installing my work there, I talked with really lovely installers and I do find it absolutely shocking that we still use inches and feet. It’s so absurd that I can only shake my head thinking when we’re going to get the metric program… ”.

This is how we realized the first important fact about her painting; it is not an enigmatic one, like in the cases of Edward Hopper or Felice Casorati, just to name a few of the many realist painters who, during the last century, preferred to leave the door open for interpretations. On the contrary, Conway intends to speak clearly and make you fully understand her message. As a creative journalist, or maybe an honest storyteller, she is not worried about telling you something.

“From a gender point of view – Conway asserts – I find Donald Trump very offensive. He has been a long-standing, very sexist and frightening kind of man who objectifies women. Politically speaking he is pretty confusing. I think he is a bit of an actor, and I don’t even understand where he is coming from. It’s going on and on as a joke. It reminds me of ‘Being there’, the Peter Sellers’ movie about this naïve and uneducated gardener who becomes accidentally famous by speaking in almost parables about gardening, while people think he is talking about economy. So they attribute him a lovely intellectual profoundness, in fact he is just a very simple person.” Do you think that Trump is just playing a role? “He is like a construction really. It seems like a joke that has just gone too far” she replies, while a small cute dog jumps on the brown soft sofa where she is comfortably seated.

“He” is her “little old friend” Walter, she adopted him. He lived in a cage for five years, in a puppy mill as a breeding dog. She remembers that at the beginning of their relationship he was so shuttered and shy that she was barely able to feed him. “But now he is so attached to me. If I am standing too far from him, he moves right up against me. It’s funny to have this little, tiny guy always around you. I couldn’t give him up, initially I fostered dogs and re-homed them, but I kept him. It’s been already seven years that we are living together”. And Walter is not the only one living with Conway. She got married a year and half ago to an old friend and she also has a five-year-old daughter from a previous relationship. The three of them came to Italy in occasion of the opening of Conway’s exhibition at the Collezione Maramotti. In other words, as most of the realist painters of the last century, and as many good contemporary novelists too, we would say that Anna Conway regards art as a functional part of a quite normal life, and life as a functional part of a quite abnormal art practice.

She explains us that she works either standing or sitting in front of the canvas. The beginning of her paintings are pretty “athletic, really loose and gestural; nobody can believe how they end up”. She instinctively throws painting all around, dripping colours and lines here and there. But in the making the image gets slowly under focus, and all that small, precise details emerge from the matter. As for these details, she confesses that she still gets surprised about how much something so tiny can actually change the entire image. “A good example – she says – would be the painting I made in 2004 and called ‘Somebody call Someone’. It’s a very dark stadium of white water rafting. It’s night and there is someone fixing something – a machine that can generate white-water rapids – inside this frothing water. I was working on that, and at some point I painted the tips of the poles in bright orange, and it felt like such a dramatic small thing that changed the whole painting for me. I remember that it felt like painting a giant, as overwhelming atmospherically as a Rothko’s, where you are absorbed in pulsing colours. And Rothko himself believed that it was enough for him to experience as a painter and, I suppose, to transmit that feeling.”

In regards with Rothko and his decision making processes in painting, Conway notices how he seems so powerful and self confident. She compares him to Ronald Regan, who seemed a powerful president already when he was a child. “But then he died, like an ordinary old man, and nothing really mattered about him dying. I used to dream regularly about Mikhail Gorbachev’s spot on his head and I’ve realized that I don’t even know whether he is still alive or not. How can it be that someone who has been so important for the world is now forgotten?”

It is said that in 15 years Anna Conway has painted just 26 paintings, and many people who have seen her at work think that she could have made 10 paintings out of each single one. Apparently she constantly makes changes, and it may seem that her art practice is all about consistency. But it is not like that. She tells us about the financial problems she had to go through after the college, due to the school debts that she accumulated in the meantime. “The day of my graduation I worked an overnight shift at a hotel. I had a lot of jobs at that time; trying to survive financially was a crazy struggle. I felt a lot of pressure over me”. The first time she was not forced to teaching came in 2014, when she won the Guggenheim Award. “Since then I have been able to produce a lot more works, because I didn’t have all that pressure about living in the United States, paying for my health insurance, being able to afford a studio, and trying somehow to survive here in New York City”. She remembers that to comfort herself from the fear of an unstable art career sometimes she would think about Henri Rousseau, who was a toll collector. Like the French master, she doesn’t come from a family with money and at the beginning of her career she just didn’t have the privilege of being a painter. “I painted such a small number of canvas in that period out of necessity, not because of an artistic choice”.

Conway worked at Columbia University, Brooklyn College, Cooper Union, but currently she is not teaching; she has taken some time off. “I am still in touch with some students, I write recommendation letters, and I am very close to some of them”. Like Nick Cortese, that she has met at Cooper Union. She mentions him when we ask her who is the most promising one among her students. “He struggled a lot to become a working artist, I’ve been supportive of him. We really admire each other’s work. It’s not an easy life being an artist.”.

Conway herself studied at The Cooper Union, and at the Columbia University School of the Arts. “My favourite artist at that time was Dana Schutz. I went to Columbia with her and I am very fond of her painting. If I haven’t seen her work in a while I am thirsty for it.” As if they were Flemish masters from the XVII century, both Schutz and Conway are inquiring into the every day in order to produce stories. Like certain contemporary novels, their paintings generate somehow truthful parallel realities, starting from the official reality and personal experience. As, for instance, Jonathan Franzen did in Freedom. But “I hated that book”, Conway claims as soon as we mention it. “I’ve read The Corrections when I was young and I loved it in the way that I loved A tale of two cities, by Charles Dickens, which is my earliest memory of feeling embarrassed about the amount of feelings I had for something that was, in fact, not real. I still remember the shock that my body felt when Sydney Carton, the protagonist, dies. I could cry by telling you what he says as he is going under the guillotine… it is a far, far better thing that I do, than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest that I go to than I have ever known. It’s funny as I don’t like watching movies, at all. Yet I like fiction a lot and I love the privacy of a novel. However, I consider Freedom as being quite artificial and forced. It may be that I am too judgemental, but I immediately thought, for instance, how stupid was the name of the band chosen by Richard Katz, one of the protagonists. Actually I never believed any of the characters.” A novel, like a painting, must be trustable, or at least look so. And that is particularly true in the case of Conway’s work, even if she particularly likes those paintings which “have not the job of conveying anything about a character, except the painter’s character.”

She has good memories of her early years in Foxboro, Massachusetts. She grew up in a nice albeit mono cultured neighborhood, inhabited by a lot of firemen, civil servants and Irish Catholics. “Poetry seemed elitist and remote to me – she remembers – until I finally listened to a talk on Wallace Stevens. He is an American poet who struggled with words to convey some really strange feelings that seemed important enough for him to be transmitted. He was also in the insurance business, and he worked for all his life, even as he became a famous poet, while still alive. I think about how careful a poet has to be, because he has to try to transmit almost private abstract feelings.” Here is the link with painting. “I don’t want be an elitist. I don’t want my audience getting smaller and smaller. It would make me sad. I want to be able to speak plainly”. And here we are, back at the beginning of our enlightening conversation with Anna Conway. Apparently it’s all about everyday life, feelings, and truthfulness. There is no need of being mysterious when you have this kind of targets and as a middle-schooler you wanted to be a famous pianist.

December 15, 2017