Mark Coetzee: ‘Rather than discovery, I call it a re-correction of ignorance’

First Zeitz MOCAA executive director and chief curator reveals his strategy to keep the about to inaugurate contemporary African art museum free, open and dynamic.

- Mark Coetzee, Executive Director and Chief Curator, Zeitz MOCAA.

- Cyrus Kabiru, Macho Nne 09 (Caribbean Peacock), 2014. Courtesy of Zeitz MOCAA, Cape Town.

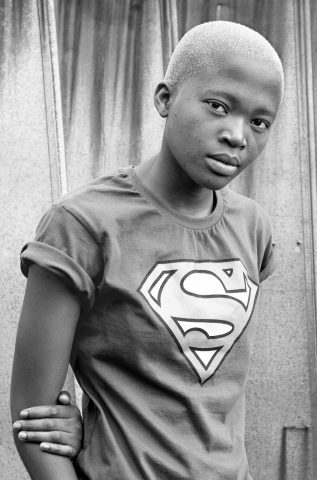

- Zanele Muholi, Mbali Zulu, KwaThema, Springs, Johannesburg, 2010. Courtesy of Zeitz MOCAA.

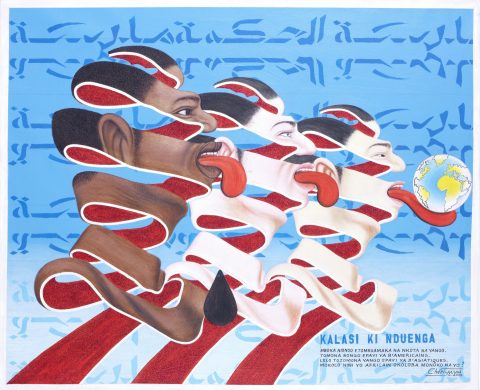

- Cheri Samba, Kalasi Ki Nduenga, 2005. Courtesy of Zeitz MOCAA, Cape Town.

- Wangechi Mutu, Second Born, 2013. Courtesy of Zeitz MOCAA.

- Zeitz MOCAA, designed by Heatherwick architects.

Mark Coetzee is the first executive director and chief curator of the brand new Zeitz MOCAA in Cape Town. The long awaited museum of contemporary art from Africa and its diaspora is going to open to the public next September, with 6500 square meters of programmable space and a brand new glass building designed by Heatherwick studio. Mr Coetzee agreed to tell CFA how this pivotal art institution will look like and what needs it will try to meet. He is 53 year-old, hence one year younger than the museum main promoter, German business and art collector Jochen Zietz, a former CEO at Puma. Coetzee was born in Johannesburg and he studied art history at the University of Stellenbosch, at the University of Cape Town and at the Sorbonne in Paris. He is also an artist and writer. Between 2001 and 2009 he directed the Rubell Family Collection in Miami, then he was appointed program director of PUMAVision and chief curator of puma.creative. Since 2007 Puma has been part of the French retail conglomerate Pinault-Printemps-Redoute (PPR).

Could you tell us about the Zeitz MOCAA financial structure? Would you call it a private or a public institution?

Mark Coetzee: The museum takes both private and public funding. Therefore it’s a public not for profit institution which is also supported by a large percentage of private funds. It’s like the MoMA, or the Guggenheim, or the other main museums in the United States which are privately funded. I see there is a lot of misunderstanding about how museums are funded nowadays. In Europe, for instance, most of the museums have the 30% of their funding from the government sources, while the Tate and the Serpentine have massive fund-raising departments to keep those institutions open.

What percentage of the museum’s budget is provided by the local government?

Mark Coetzee: The renovation of the building was paid half with private funds and half with money from a government entity. Certainly the Zeitz is not something like the Broad or the Rubell Museum. These are fully private museums supported by a single family, which run them like private projects. But in our case it’s still too early to say exactly what percentage of money will come from where. What we wouldn’t like to do is taking money from the government, because we are in a very particular moment in our Country, with problems about housing, schools and water provision. We also have to be very careful and make sure to position the museum as a public institution, and also as an institution with full freedom of expression

Would you call the Zietz a museum about contemporary African art and its diaspora, or just a museum of contemporary art based in Africa?

Mark Coetzee: The Zeitz is very much about Africa and its diaspora, and I think this is a very strong commitment we made. Nevertheless the definition and the interpretation of that is also very open. We would say the museum is about Africa and its influences through the centuries. It is trying to look at Africa’s place in the world, Africa’s influence, and the dialogue about Africa. The museum is enormous. There are nine floors, some of which are dedicated to the permanent collection. We exclusively collect art from Africa and its diaspora. But there are also temporary exhibition areas which function more like Kunsthalle, where we will host temporary exhibitions from all over the world, with international artists. It is important that we open up the conversations and that our creators also get an opportunity to see what’s happening elsewhere.

In Venice at the African Art in Venice Forum Mr Zeitz said that the MOCAA wants to guarantee an access for all, be an open place, a museum for Africa. Could you elaborate on it?

Mark Coetzee: This means many different things. First of all, it means financial access. The museum has worked very hard in fundraising to make sure that there are opportunities during the week to access it for free. We can’t be free all the time at the moment but we hope one day we will be. In Africa even the smallest little admission fee can mean that a large proportion of the society cannot access the museum. That’s something we work very hard on. Just as important, access for all means that when you enter it your culture is represented. A lot of people have in mind the UN declaration of human rights where voting and equality come first. However, if you read further down it also talks about culture and it says that access to your cultural representation and participation in your own culture’s activities is also a human right. Unfortunately the way that museums have been conceived in the past – and I am not talking about newer museums –, doesn’t seem to respect this right. Sadly they were places for the privileged. But now museums are trying very hard to become more accessible. If you look at contemporary museums, they have completely changed the infrastructures of the building. The facades have opened up; they are made of glass and you can see what’s happening inside. We, as Zeitz Museum, not only have to change the physical structure and the internal operations, we also have to address a community who has been excluded from cultural participation for fifty years and make them feel that they are welcomed again. We have a big job ahead and we have been trying very hard to make sure that there is no community that does take the ownership of the museum. We need the communities to feel that this is their museum and we are just the care-takers; it can’t belong to us.

Is the Zietz going to be the main contemporary art museum in the Continent?

Mark Coetzee: That’s difficult for me to say. We are certainly going to be the biggest and I suppose only time will tell. It’s a magnificent building and the collection is amazing. Yet, the reputation of a museum also depends on the content, how sophisticated and relevant that is as well as on the curators, who will show us whether this museum is going to succeed or not.

Would you make a division between Sub-Saharan Africa and Africa as a whole?

Mark Coetzee: The way that we see Africa is very often through Western eyes. Most of the division of the states in Africa were indeed defined by European colonial powers. Very arbitrarily they sliced up the continent. Unfortunately some people have also tried to divide Africa, in the sense that north of the Sahara, is the Mediterranean and south of the Sahara is the real Africa. Are all these divisions helpful? They certainly demonstrate how this continent has been violently opened up and put together, broken up and put together, many times not by Africans themselves. Part of the mission of the Zeitz MOCAA comes from this idea of creating an institution where Africans, or people in Africa, can at least contribute to the dialogue of how Africa defines itself. A lot of people have pointed out that Africa is not a country, but it’s the people state. Hence, the questioning on how there could be just one institution to represent Africa. On the other hand there are some artists who are simply tired of everyone outside Africa trying to split up Africa by dictating whether you are African enough. The museum will attempt to facilitate these conversations about what is Africa and what defines Africanness. Is it geography? Culture, food, skin colour, language? Or is it purely that we all are on the same piece of geographical land? Someone asked me this question a couple of years ago. Up until recently I don’t think that an European would wake up and question himself whether he is an European. You are French, and you are an European. You are Italian, and you are an European. I am not talking about the European Union, I am talking about the identity of a place. Why does everyone expect us Africans to be so broken up? I am South African and I can be African.

From a Western perspective it seems that there are a lot of opposite energies. Museums, institutions and art fairs should try to harmonise all these energies around.

Mark Coetzee: When I travel, and look for works for exhibitions, I find main themes which run through artworks in Africa, but also around the world. For instance recently we have seen a lot of works both in south and north Africa by women artists who are talking about the transparency of female in society. Do they do it in the same way? No, they don’t. The artists from south Africa may be very aggressive and very confident. The artists from north Africa are a bit more poetic. But in the end, the pressing issues are the same and that is what unifies Africa and also what unifies this continent with the world. Artists have always dealt with things for art sake, but also with social issues. We always expect an artist to do that in a very honest, straight forward way. Of course we are different; we are a complex piece of land, with 54 countries, with many different cultures in each country, and languages, and traditions. But that doesn’t mean there aren’t similarities as well. First of all, we are bound by the way the European powers treated Africa.

We should also mention the contemporary colonialism by Americans and Chinese…

Mark Coetzee: I was trying to find a polite way to put it… it is indeed a new invasion for natural resources. One of the greatest sadness for me as a young man was that everything I studied about in art history was European. What I studied about Africa was limited to a very short period. It has now changed, yet a lot of time is still spent on Europe and European tradition. We would spend four years on Greek, Roman, Egyptian, Renaissance… and only one day on Africa. Even the things that we have studied weren’t in Africa, like the Elgin marbles that are in the British museum. We understand that it is part of art history but there is a new kind of economic colonialism, or imperialism. It is a fact that nowadays there is a growing interest in Africa. Very often the institutions on the Continent cannot afford to purchase anything for their national collections, and all the important works are leaving the Continent yet again. And it’s only thanks to people like Sindika Dokolo, the Zeitz collection and a few other institutions that are managing to protect some objects for the Continent. This is a reoccurring theme.

What does this current interest in contemporary African art depend upon?

Mark Coetzee: The art-world seeks things that are fresh, not being seen before, challenging. And that is probably the main reason why African art is so on demand at the moment. On the other hand, for a very long time there has been a preconceived idea of what kind of work is art from Africa and now this idea is rapidly changing…

So what is making this change so quick?

Mark Coetzee: In the past artists really needed an art dealer or a publisher to promote their work broadly. Nowadays, with all the social media platforms and web sites, artists can make the world see their work in a very inexpensive and quick way. I think the web really expanded the art-world.

According to many early collectors of contemporary art from the Continent, African artists were already there twenty years ago.

Mark Coetzee: They are right. As a matter of fact artists have been making works in Africa for a very long time, but people from the Northern hemisphere have been very naïve to what has being happening in the world. They were used to focus their attention only on regions around themselves. Today, thanks to internet, the world is becoming more and more aware of a broader practice of art, which also includes Africa.

During a recent panel at Open Care in Milan, director of 1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair Touria El Glaoui asserted that 95% of the collectors of contemporary art from Africa are not based on the Continent. What do you think these people are looking for when they buy art?

Mark Coetzee: Africa is still going through a post-colonial period, but there is also a new generation of young people who consider themselves Afro-futurists, or Afro-positivists, and they believe in the future of the Continent. That is probably why Western collectors are interested in the Continent. They feel the freshness of the materials, the authenticity of the contents; they like it for it is real. At the same time part of the responsibility of the museum is also to inspire and encourage new collectors on the Continent. The collector-base and collector support in Africa is growing but it’s something that has to be cultivated and nurtured.

Could the idea of discovery be also what they are looking for?

Mark Coetzee: First of all we should distinguish between discovery and naïvety. This is not about discovery, this is about naïvety. The Victoria falls didn’t start the day Livingstone discovered them. Actually he didn’t discover the falls. He only discovered his ignorance in not knowing about them. This is also what is happening in the international art-world. Many collectors and museums at some point realized that contemporary African art is part of the history of humanity, as the Chinese art, the European art, or the art from South America. Most museums collected African masks and drums, and anthropological art effects. But they didn’t collect contemporary art, and now they realize they were wrong in excluding it. Rather than discovery, I would call it a kind of re-correction of ignorance.

We would say that the main risk, now, is taking Africa as a new Eldorado.

Mark Coetzee: Everybody is trying to communicate this fairy-tale about Africa. Now it seems that Africa has been included in the art system and won’t be excluded again. But it isn’t necessarily so. I’m concerned that this attention Africa is gaining will soon move somewhere else. It’s inevitable. How do we deal with that? We could be naïve and believe it is not going to happen. Or, we can be aware that the fashion may turn somewhere else at some point. In this case the museum will have to maintain some attention on the Continent, facilitate research and keep the participation of artists from Africa in everybody’s mind on a consistent basis. At the same time we have to make sure that artists from Africa remain part of the international dialogue, hence our sustainable model, that is collecting Africans but showing everything.

July 4, 2017