Cleo Fariselli, dominant chords

Cleo Fariselli’s upcoming solo exhibition proves the Turin-based artist is finally ready to explore painting and look beyond duality (thanks to a new periscope).

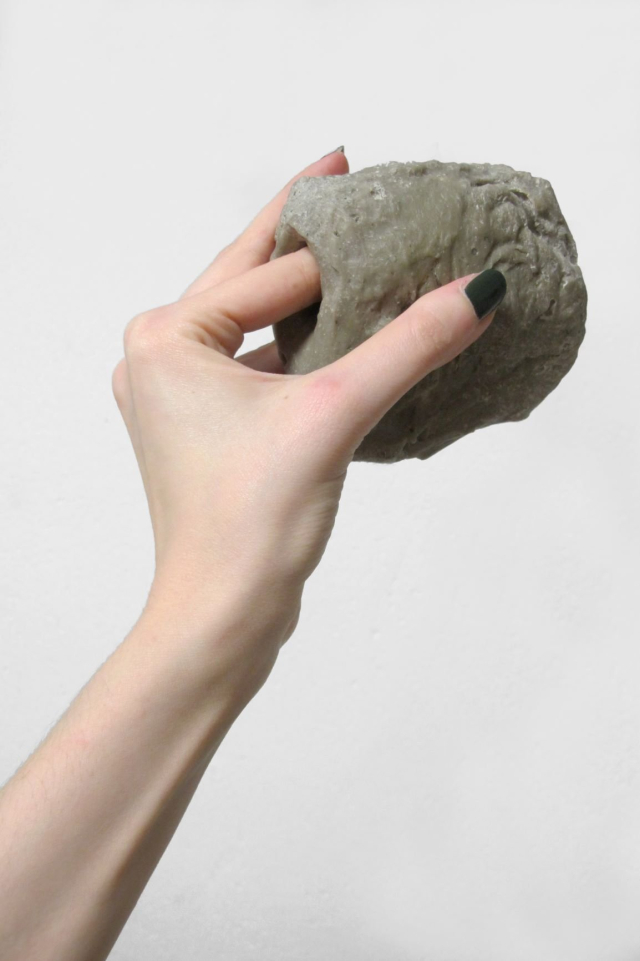

Cleo Fariselli, Fon Gran Papa III, detail, 2019, dental ceramic plaster, clay sediments, cm 31 x 60 x 26, photo: Silvia Mangosio and Luca Vianello.

—

The art practice of Cleo Fariselli deals with errors, even if you wouldn’t say so. This is actually what we discovered when visiting her studio, located in Turin, one of the many ‘Berlin’ of Mediterranean Europe – that is to say one of those cities which, as opposed to London or Paris, still has some room for artists.

The discourse around the dualism between ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ that the dental ceramic plaster sculptures belonging to the series ‘Gran Papa’ suggest can trick you. It seems it was generated on purpose, in order to test the viewer and his/her real motivation. We, needless to say, fell for it. The artist makes these busts, vaguely reminding of the ‘Accademia’, by digging in the clay block by hand, rather than working with it from the outside. We thought that that was it, all there, within our reach. And we asked the artist the most obvious question: “Yes indeed – says Cleo Fariselli – the relationship between inside and outside is certainly fundamental”. Yet she immediately adds: “I set certain conditions which somehow limit myself. Sight becomes less important. The sculpture arises from gesture, imagination, memory, instinct. Eyes don’t have any control of it. I discover the shape only once it is almost done, when I pour plaster into the hole I had previously made in the clay”. Another useless question, why did you choose clay? “Because it is a straight-forward element. Simple and extremely difficult at the same time” explains the artist, without really going any deeper into it though. She then changes topic and tells us about the exhibition-performance titled ‘U.’ during which Fariselli gives to the public, conveniently divided into small groups sitting in a circle, a little sculptural object. Here Fariselli questions how our perception of an object changes according to the way the latter is presented to us. In a heartbeat we are brought to theatre, an interest the artist was led to by theorists like Jerzy Grotowski and Eugenio Barba – Warsaw appears into the distance, announced by André Cadere’s bars (the following image will reveal the reason).

Cleo Fariselli, Urpe, Daboia, Taipan, Oropel, Petra, Ige, Vlada, Cinna, Nisia, 2013- 2015, mixed media on ropes, various dimensions, audio piece in collaboration with Federico Chiari, Installation view from the group show Epicentri, curated by Fabio Carnaghi, 2016, Terme di Como Romana. Courtesy of the artist.

Cleo Fariselli, Untitled, from the series Handled sculptures, 2014, inkjet print, cm 42 x 28.

The Sé and the error.

Couldn’t it be that methods and boundaries are actually expedients to define a Freudian self? Let’s take a lateral step. “To me, the most interesting substance is the one where you can encounter many dimensions” claims now Fariselli, who studied at the Accademia di Brera with the notorious Alberto Garutti, another ‘methodist’ much loved by his pupils. Her dissertation was titled ‘Art as a natural phenomenon’, and was an attempt to regard art beyond its anthropocentric perspective… “before this perspective became actually trendy” remarks Fariselli. More than in the human being, the artist is interested in the space, and in the quantum physics – this latter is nowadays an extraordinary food for thought for artists. This time however we don’t rise to the bait. “Possibly the feeding source of my work is my direct experience. Not in an autobiographical way – or diarist, we would add -, but in order to share the physicality of the matter”. This is why, for instance, there is no photographic record of the above-mentioned exhibition-performance. At some point Fariselli ‘quitted’ taking pictures, and never went back. “I was shooting a sort of visual journal, in an attempt to unveil whatever struck me. I used to photograph everything really. It was, as said, experience. I wasn’t interested in the subject as such, but in the way I saw it and managed to capture its being extraordinary. However, what has been for me, up to a certain point, a way to intensify the experience, then it got lost in the immense flow of digital images that are continuously generated and shared on the web. This act of documenting sickened me to such an extent that I have never taken a picture again”. What Fariselli is trying to do nowadays is, instead, “offering some starting points for self-analysis and for observing the reality, which could also be addressed to the outside”.

A self-analysis.

Let’s focus on the former, that is self-analysis. The self Fariselli talks about is not autobiographical. Her refusal to use the photographic medium as a diary is not only a way to escape the homogenisation imposed by the social media, which by now know about us much more than what Doctor Freud could have ever hoped to know. Rather, this self is the test of a boundary whose nature is probably more similar to the one that Fariselli has encountered in theatre or in music. The artist studied piano for a very long time, possibly more intensely than others, considering she is the daughter of a brilliant composer – Patrizio Fariselli. These are indeed the spaces between dimension and dimension that the artist first discovers, then experiments. This is the meaning of the footprints her body left on the clay (finger, ear, shoulders, breasts, buttocks). The error we were talking about may represent that boundary beyond which the medium takes over the creative act – that, not only for musicians, arrives way before than becoming an actual expert. Initially the error is not a problem; on the contrary, it is a resource. Here is the Gran Papa ‘inverted’ sculpture, that has been generated by excluding the supervision of the sight.

Cleo Fariselli, Fon Gran Papa I, detail, 2019, dental ceramic plaster, clay sediments, cm 28 x 64 x 25, photo: Silvia Mangosio and Luca Vianello.

A solo show at the Collezione Giuseppe Iannaccone.

Amongst the Gran Papa, the pieces exhibited in the solo show Collezione Iannaccone dedicates to Fariselli are the strongest ones, that is those the artist’s hands have dig the deepest (they are indeed called Von Gran Papa, i.e. great-grandfather in creole). The resulting images are more primitive than the previous ones. The dialogue in the dark with the physiognomical figure becomes extreme, at the limit of comprehensible. Error, or chance, are thus assimilated in the process; they go beyond the method. The same happens with painting, the new boundary Fariselli decided to move towards. The two new paintings (on board) are titled ‘Torrente’ (the smallest one) and ‘Paesaggio acquatico con bisce’. They call to mind the delicate foliage of certain late 15th century paintings.

Cleo Fariselli, Torrente, 2019, oil con wooden board, cm 90 x 60 (unframed)

photo: Silvia Mangosio and Luca Vianello.

Cleo Fariselli, Paesaggio acquatico con bisce, detail, 2019, oil on wooden board, 120 x 90 (unframed) photo: Silvia Mangosio and Luca Vianello.

The hollow head made of clay, resin and scagliola, also on show, is installed on a rotating pedestal so that the sculpture’s gaze is placed almost at the same level of the artist’s one. However, if you are not too tall, in order to look through the hole on its nape, you will have to stand on the tips of your toes; pretty much like a child who tries to look in those coin-operated Tower Optical viewers (title: Scopio). “It is actually a mistake of the blacksmith – explains Fariselli -, the head is too difficult to reach”. Then she goes on to tell us that since her early childhood she has been suffering from a vision development disorder also known as lazy eye (amblyopia). Basically, it happens that one eye has much better focus than the other. “Looking through the hole on the nape of the sculpture is a bit like how I see the world”.

Cleo Fariselli, Scopio, 2019, plaster, epoxy resin, micaceous pigment, scagliola carpigiana coating, distilled water, iron base, cm 33 x 25 x 28 e cm 55 x 140 x 55 photo: Silvia Mangosio and Luca Vianello.

March 21, 2019