At the Met with Silvio Wolf, from Tintoretto to Baselitz

At the show with the artist: Silvio Wolf takes us to the Met to discover a portrait by Tintoretto and questions Georg Baselitz about Lucio Fontana.

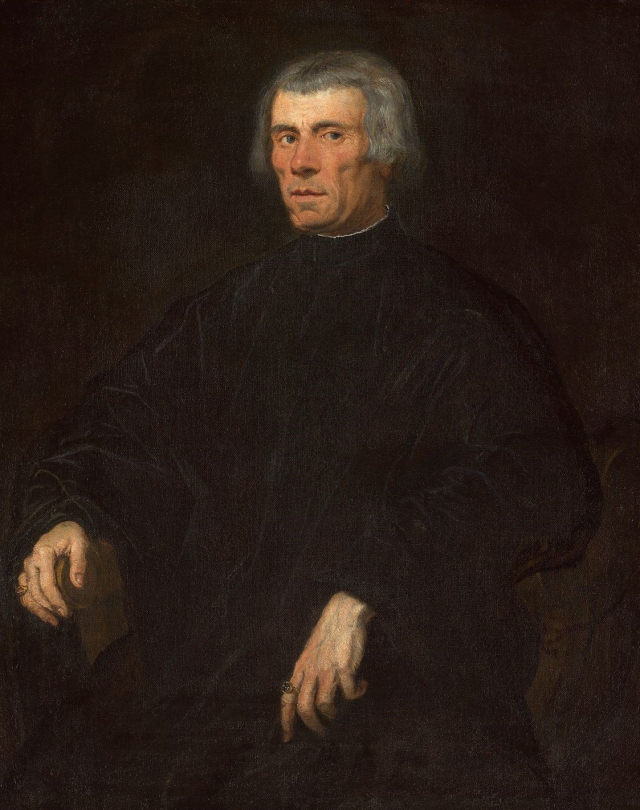

Jacopo Tintoretto, Portrait of a man, 1550s, oil on canvas, 44 3/8 x 35 in. (112.7 x 88.9 cm). Gift of George Blumenthal, 1941. Courtesy Metropolitan Museum, New York.

—

Who was the wealthy, respectable, finely dressed middle-aged man sitting still in Tintoretto’s studio?

Who was pondering over the stages of his own life and the events that had led him to that place at that time before the painter so that that portrait, still unknown to his eyes, would outlive him through the eyes of the artist?

What image of himself was he projecting on the flat figure that would have granted eternity to his ephemeral life?

All the events, coincidences and necessities of time and of history, the choices he made and those he didn’t make, the decisions he reached, the sacrifices, regrets, doubts, the facts that occurred in their tragic yet unique exactness had led him to be that Portrait of a Man. He knew that by offering himself to the eye, hand and heart of the artist he would cease to be whoever he believed to be, to become whoever the other one wanted him to be.

There he becomes image, surrendering and fading away, stopping, posing then appearing in the flow of time and of history, thus transforming substance (body) and spirit into a visible projection of the Other. Through the painting his portrait, Tintoretto was taking away in order to give back; prying out to offer; limiting to make him in-finite thus transforming him into a symbol of being, having been and being able to be again.

He lived, died and was buried around the middle of the 16th century; that Man is now hanging on the walls of the Metropolitan Museum in New York where thousands of eyes can look at him and not him, him but not him; the Man and the other Man, the artist and his model, the screen and the mirror.

Tintoretto’s Man is the future of the past, the artist who represents himself through the other’s virtual body, ashes mixed with oil on canvas; the time of those lively yet motionless, deep eyes that call everyone into the present moment of life.

In the noble rooms of the Lehman collection, where only whatever shall be remembered, celebrated and admired, protected and studied finds a place for the human celebration of the History of Art, the Man and Tintoretto exchanged and reflected identity and persona, forever blended into their ‘Portrait of a Man’.

Georg Baselitz, L. F., 2018. Oil on canvas, 60 5/8 x 42 15/16 inches (154 x 109 cm). © Georg Baselitz. Photo: Jochen Littkemann. Courtesy Gagosian.

The portrait of Lucio Fontana by Georg Baselitz.

Meanwhile, at Gagosian Gallery another man emerges from that alchemical mixture of time and oil on canvas, another face comes back to light: the self-portrait of a painter depicted by another painter.

Two men, who had never come across each other, whose gazes had never met, recreate their own image: it is the oil portrait on canvas painted by Georg Baselitz inspired by ‘Lucio Fontana’ pencil on paper self-portrait.

The painter gives life to his face, thoughtfully suspended, motionlessly upside down, depicting it with the bright thickness of his rough and material oil painting.In the white lay cathedral of contemporary art where images are celebrated, exchanged and protected, a universe of painted faces reveals that of self-portrayed artists, whom Baselitz recreates with thought and graphite, gaze and pastel, oil and imagination.

Once again the image performs the miracle of figuration and substitution, of commitment and challenge; it brings back to life and reminds us of death through the tremendous power of stating the present, always representing only the past.

“Men have created an image of everything” [note 1] visible and invisible, of their own bodies, faces and gazes, of desires and expectations, of fears and dreams.

Through the cult of representation, identification and deception, of being and becoming, could an image convey in finite forms what is constantly flowing and changing with every new gaze?

If what we see is a perceivable form of our thought that is reflected in what already is, how can we depict what exists independently from us?

If being and not being are the simultaneous condition of the I in search of eternity, what is concealing in the Infinite Present of the human appearance?

What is constantly leading us to create an image: to become an image?

How does the idea of a work of art come to life? This remains the more mysterious and unfathomable process. It looks like it develops independently, out of our control, in the subconscious, where the idea crystallises within the wall of our soul. [note 2]

—

* Silvio Wolf (1952) lives and works between Milan and New York. Since the early 80s his work has been exhibited internationally including New Image (1980, Milan), Aktuell ‘83 (Munich), Documenta VIII (1987, Kassel). In 2009 he was invited to participate in the 53rd Venice Biennale. The artist currently teaches at the European Institute of Design in Milan and is a visiting professor at the School of Visual Arts in New York.

Notes:

1 In Wim Wenders, Faraway, so close!, 1993, Angel Raphaela to Angel Cassiel.

2 In Andrei Tarkovsky, Sculpting in time, 1986.

April 23, 2019