Neo Rauch: ‘A painting should be more intelligent than its painter’

We sat down with Neo Rauch in New York, where the Drawing Center is dedicating a comprehensive exhibition to his drawings. The artist’s creative approach has never been more clear.

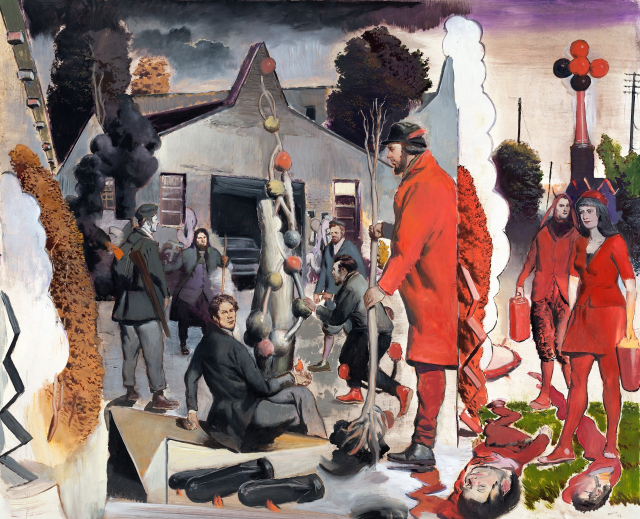

Neo Rauch, Der Stammbaum, 2017. Oil on paper, 66 1/4 x 81 3/8 inches (168.28 x 206.69 cm). Courtesy the artist, Galerie EIGEN + ART Leipzig/Berlin and David Zwirner © Neo Rauch, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

One of the most universally admired painters working today, the German artist Neo Rauch is now being celebrated for his drawings—with 170 of them, spanning some 30 years, currently on view at The Drawing Center. Working mostly in a stream of consciousness manner, Rauch lets figures and scenarios develop from his imagination on paper. Somewhat of a witness to the making of his own work, Rauch recently sat down with Conceptual Fine Arts to discuss his process for creating the uncanny drawings in this survey show.

What role does drawing play in your art making?

I wouldn’t describe myself as a draughtsman because drawing just happens for me. I’m a painter and I don’t use drawings for preparing paintings. I let ideas stream through my hand to my brush or my pencil and don’t think about what I do. There’s not much difference between the way I make drawings and how I paint. It’s almost the same.

Do you recall when and why you first started drawing images?

When I was two years old I drew a woodpecker. I should try to find it and show it now.

Do you draw with a subject in mind or does it come from the process of putting pen or pencil to paper?

As I said, I let it flow; I let it happen. It develops by itself on the paper. I have no plan when I start.

The earliest drawings in the show have a relationship to graphic novel or cartoon imagery. Were you a fan of these forms of illustration when you were growing up?

Sure, I’m still a big fan of this kind of drawing. It’ a very important and underestimated way to describe the world and the human condition. Graphic novels and cartoons and comics are definitely underestimated in the art scene.

Has your work always been figurative?

Yes, but in the late-80s I started some risky enterprises in the direction of abstraction. It was a dangerous path because it brought me close to losing myself—losing the main streams that I could feel deep inside my being, deep inside my mind. It was an important experience to be in a position where I could see myself disappearing from my basics. What rescued me was the experience of seeing Giotto in Assisi in 1990. I travelled to Italy and was overwhelmed by Giotto’s frescoes in Assisi. They were so strict and well organised that they brought me back to figurative painting. (Giotto has influenced another contemporary artist, Nicolas Party. Here the link to our story about this topic)

I’ve read that you don’t like the term Social Realism applied to your work, but was realism an influence when you were schooled in Leipzig?

Realism, yes, but not Social Realism; even my teachers were no longer influenced by this style. Politics didn’t outweigh aesthetics at the Academy of Fine Arts in Leipzig when I went there. The director of our art school said that he would avoid the influence of the Communist Party on the student. We could develop our intentions in a peaceful atmosphere, where we could concentrate on having a good time.

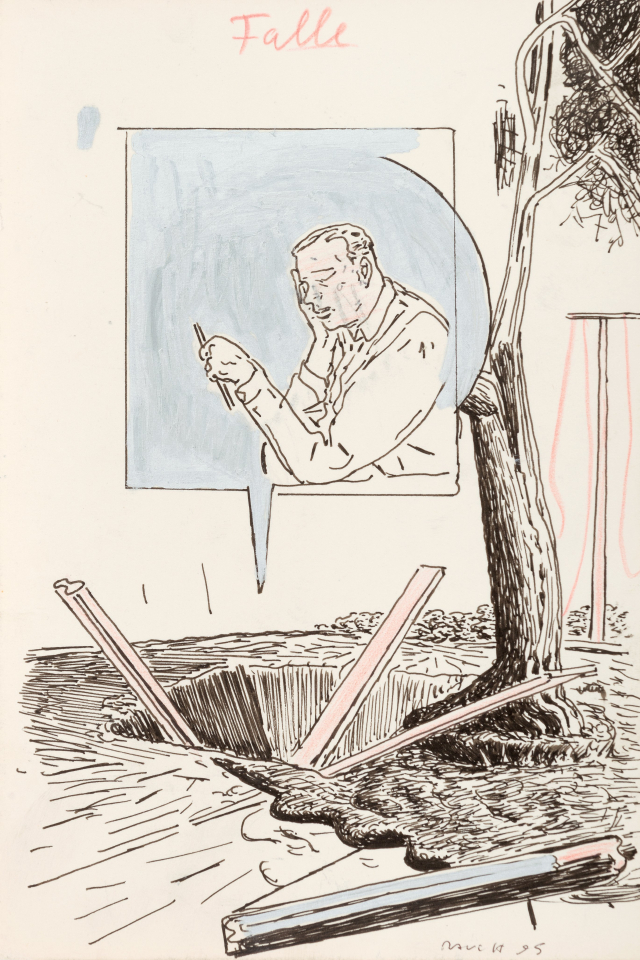

Neo Rauch, Falle, 1995. Felt tip pen and crayon on paper, 8 3/8 x 5 5/8 inches (21.27 x 14.29 cm). Courtesy the artist, Galerie EIGEN + ART Leipzig/Berlin and David Zwirner © Neo Rauch, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

In the catalogue for the Drawing Center show exhibition co-curator Brett Littman mentions that you sometimes draw on a tree stump in your studio, which seems a bit surreal. Has Surrealism also been an influence on your creative output?

Yes, when I was 15 or 16 I was deeply touched by the work of Salvador Dalí and René Magritte. Their positions influenced me a lot and led me to attend art school in Leipzig. There was a teacher there who was also influenced my Dalí. It was Arno Rink. For me, there was no other way to come close to this wealth of inspiration than to go to the Academy of Fine Arts in Leipzig.

Are you recording your dreams in your work?

No, my paintings and drawings don’t mirror my dreams. I’m interested in simulating the mechanisms of dreaming—as if I am dreaming. I have to tune out my brain to make sure that I get into a certain stream of the subconscious.

Are you a doodler?

Yes, many of the works in the show are doodles. Some works are more born by doodling than others. I had no intention of showing many of these works—works that Brett Littman found on the floor of my studio. We have a saying that translates something like “the matting of a piece is what makes it art.” When properly presented, even a shabby piece of paper can look like art.

How much of the environment that you inhabit is revealed in your work?

The landscapes and certain types of roof shapes and church towers often appear in my work. I’m definitely influenced by the landscape and architecture of my realm.

Are there reoccurring scenarios for your characters?

There are returning elements—windows and trees. Snakes and dragons reappear in several of the works in this show—especially in the lower part of the finished paintings on paper here. There seems to be something happening at the embankment that’s dangerous or uncanny.

Are the characters drawn from historical sources or do they represent life today?

I would say both. What I’m doing is about timelessness. I’m trying to avoid being fixed in a certain decade. It’s about a longer distance of time.

Is your work metaphysical?

I hope it is. The way it appears makes me also wonder if it is. I ask myself, “where did this come from? Who advised me to do it in this way and not in another?” I could describe myself as a medium. Yes, I would go as far as to say I’m a medium, not a brain-guided artist. I’m a painter, not an artist.

What does the indescribable represent to you?

I would say that painting is responsible for representing indescribable and unexplainable things—things that words can’t fully represent. That’s where painting comes in.

What role do your titles play?

I would actually prefer to keep them untitled, but it would be a mess for the galleries and collectors—even for me because everything needs a name. It’s not always easy to name them, but sometimes a title comes first; there are certain words that make pictures appear.

In his catalogue essay Littman also talks about your drawing as being something that you put back into the blender of your mind for further use. Is that why the actions and juxtapositions of objects and characters can sometimes appear puzzling to the viewer?

Yes—a long question and a short answer. Things can happen randomly. Sometimes a painting can be developing too strictly and then I have to intrude and throw a bomb into it to disturb things and create new levels of correspondence between the elements.

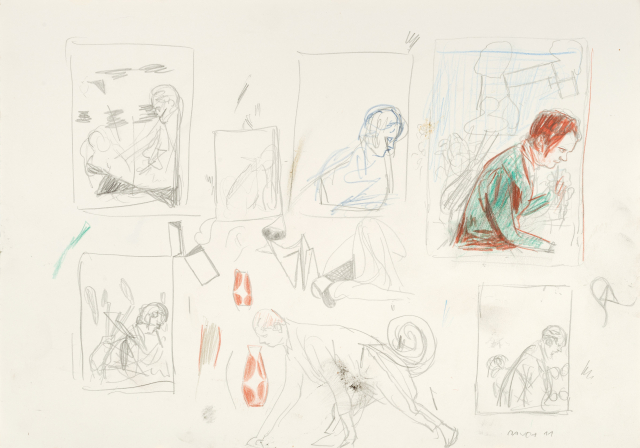

Neo Rauch, Kringel, 2011. Crayon and pencil on paper, 11 5/8 x 16 1/2 inches (29.53 x 41.91 cm). Courtesy the artist, Galerie EIGEN + ART Leipzig/Berlin and David Zwirner © Neo Rauch, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

When you were a professor, what did you tell your students about drawing?

About drawing? I guess I didn’t make a difference between painting and drawing. I always told them not to care about the art world, to stay introspective. The German painter Caspar David Friedrich said, “The artist should not only paint what he sees before him, but also what he sees within him. If, however, he sees nothing within him, then he should also omit to paint that which he sees before him.” Many students use photographic imagery for the outside world, but I always tried to encourage them not to do it, not to use this device because it takes them far from their own imagination. It’s better to take the whole adventure, even if it’s uncomfortable, to explore the caves of your mind rather than the caves of strangers.

You sometimes mix the media—such as pencil, pen, paint—while you are drawing. Is that a form of unconscious play or is it more intentional mark-making, like adding a color that you’re thinking about in relationship to making a painting?

It’s both. Sometimes I use even coffee or tea—whatever is at hand.

Other than being on paper, how do your finished or complete drawings differ from your paintings?

They are actually quite close. These are paintings; it’s just that they are on paper. The reason that I sometimes use paper is to create change, to have a different surface. The brush slides more elegantly on the surface of paper, without the resistance of the canvas. It’s relaxing, like a vacation from painting on canvas. It works the other way, too. When I’m working on big sheets of paper I start to long for the canvas. It comes in waves. The works on paper are a bit lighter because I use the opportunity to keep some areas of the paper uncovered. It gives a lighter image. Canvas can have that, too, but I don’t like the look of the unpainted canvas.

In a 2006 video interview you said, “In my own way I inhale the world around me. It flows into the brush and then reappears, transformed.” Does the world you inhale today smell as sweet and seem as full of potential as it did then?

It’s more bittersweet, like the whole life. There’s a certain taste of the limitations of our lifetime, which makes me a little bit angry sometimes and also sad. But hopefully I’m able to turn these emotions into a nice chromaticity. A painting should always be more intelligent than the person who makes it.

November 7, 2019