Museum Rietberg’s director Albert Lutz on art restitution issues

We discussed art restitution issues with Albert Lutz, leaving director of Rietberg Museum, Switzerland’s only museum dedicated to non-European art.

The theme of art restitution and rehabilitation of art is not new for museums. But the debate has sped up since French president Emmanuel Macron commissioned a report specially focused on the colonial context – that was published one year ago under the title “Restituer le Patrimoine Africain”. The authors, Senegalese economist Felwine Sarr and French historian Bénédicte Savoy, recommended the permanent return of the objects removed from Africa under colonialism to their countries of origin. Of course, the question of provenance lies behind it: a sensible yet relatively new topic, that is opening a wide scenario that is going beyond art restitution issues. We spoke about this with Albert Lutz, director of Museum Rietberg Zurich, (who is ending his mandate and retiring at the end of November after 21 years and will be succeeded by Annette Bhagwati ) and Esther Tisa Francini who is responsible for provenance research. It was thanks to Lutz that the position that now Tisa Francini holds was started at the Swiss museum. He felt the need to delve into the collection account, a matter that transcends art restitution issues to encompass history, politics and morality. As Albert Lutz explains in the following interview, the Museum Rietberg – a little jewel consisting in a few ancient buildings situated in an English landscape garden of almost 70 thousand square meters – is the only museum in Switzerland dedicated to non-European art, with a peculiar and still quite forward vision. And from the little confederation in Southern Europe, it has started to build bridges towards the rest of the world.

Unwrapping Museum Rietberg’s collection history.

Mr Lutz, by the end of November you will say goodbye to the museum you have been directing since 1998. Tell us about the museum you found when you arrived.

Albert Lutz: It’s already been 36 years since I arrived here and I started working at the department of Chinese Art. The Museum Rietberg was at the time, and it still is, the only museum in Switzerland dedicated to non-European art, holding a collection of more than 137,000 photographs and 123,000 objects (including sculptures, paintings, ceramics, and textiles) from Asia, Africa, the Americas and Oceania. The founding collection belonged to Baron Eduard von der Heydt, the man who bought Monte Verità in Ascona. Many of his goods were there when he lent them to the city of Zurich, in 1946. Four years after there was a referendum through which people in Zurich were asked if they wanted to convert the state Wesendonck villa into an art museum. It is a curious fact that despite the ruling labour party was against the project – their propaganda was stressing the link between art and the élite – the citizens of the city voted “yes”. Eventually, in 1952, the museum was opened.

That’s the villa that hosted Richard Wagner at the time when he wrote “Tristan und Isolde”. But the museum has expanded since, and you have enlarged it 12 years ago with a new building that was instrumental to a further development of its activities.

Albert Lutz: Yes, indeed. Along the years the collection has been growing through gifts or bequests, through bestowals or the acceptance of permanent loans – as well as through purchases. So, in 2007 the museum complex of historical buildings was enlarged to include a newly constructed building meant for temporary exhibitions. The current installation was in fact designed 12 years ago; while by introducing temporary shows – such as the last one, “Mirrors: the Reflected Self”, or “Gardens of the world” – we have had the opportunity to put our permanent collection into different perspectives and different contexts. We have welcomed contemporary art and we have been questioning ways of displaying. Temporary exhibitions turned out to be a booster for the public: visitors doubled. This will eventually change the way to present the collection, but we want it to evolve slowly in order to preserve its own identity. (Here is a link to our writing about Osiris, one of the most successful exhibition at the Museum Rietberg, that was about the work of archaeologist Frank Goddio)

Can you elaborate on it?

Albert Lutz: Since its debut, the museum draws on the notion of “ars una” – a definition coined by art historian and sinologist William Cohn – that has informed the way our art is displayed. Baron von der Heydt wanted to make world art accessible to a wide public and pieces from all over the world were invested with the same dignity, and considered for their aesthetic value and not as mere ethnical artefacts.

The importance of provenance researches in art restitution issues.

This is a crucial issue at the moment when it comes to non-Western art in museums. Was the Baron a traveller?

Esther Tisa Francini: He wasn’t, actually. But he was also a client in the best galleries in London, Paris, Amsterdam, New York. He had a house in Berlin and significant financial resources there that he decided to invest in art.

And when it comes to purchases nowadays at the museum, how do you decide them?

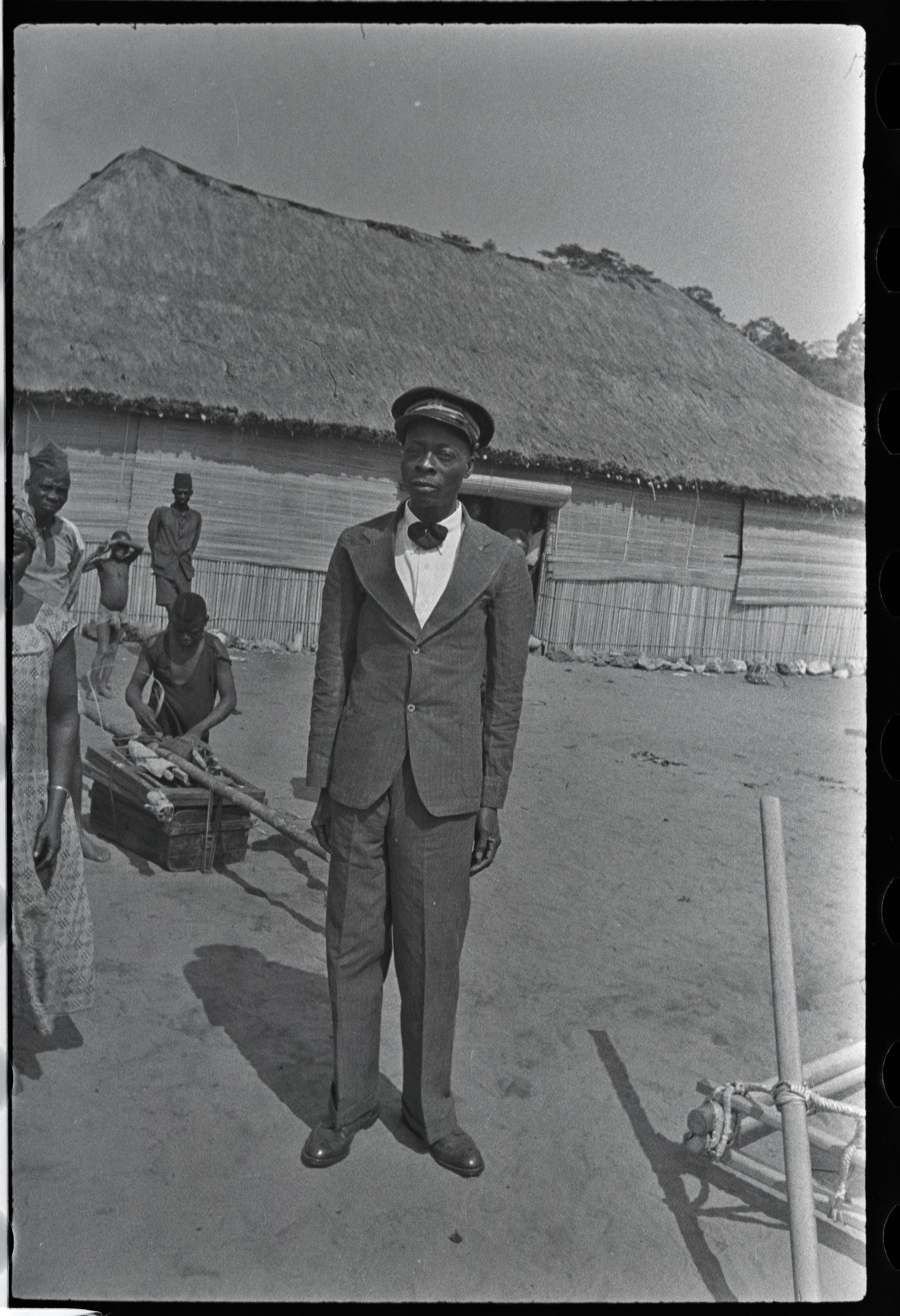

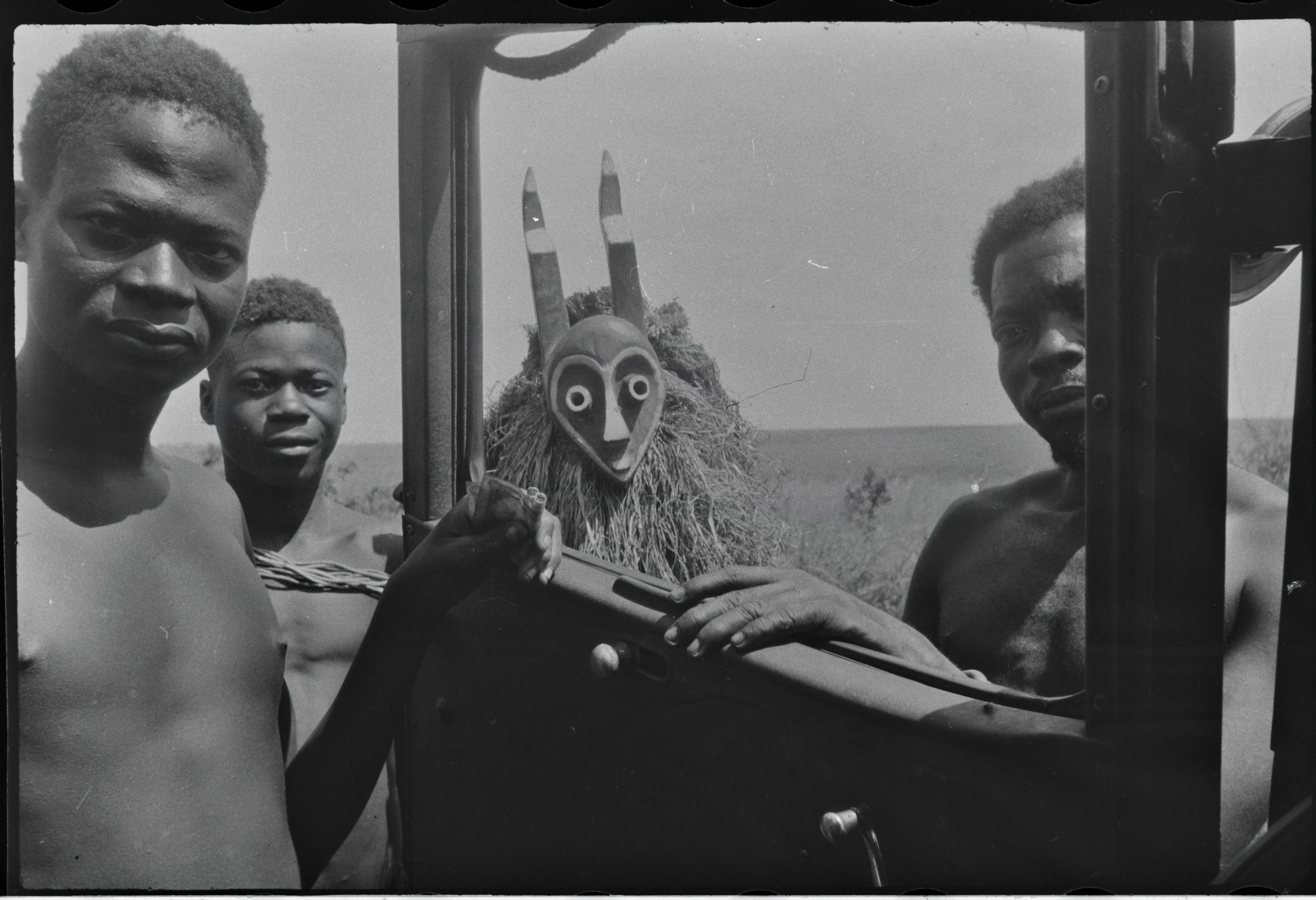

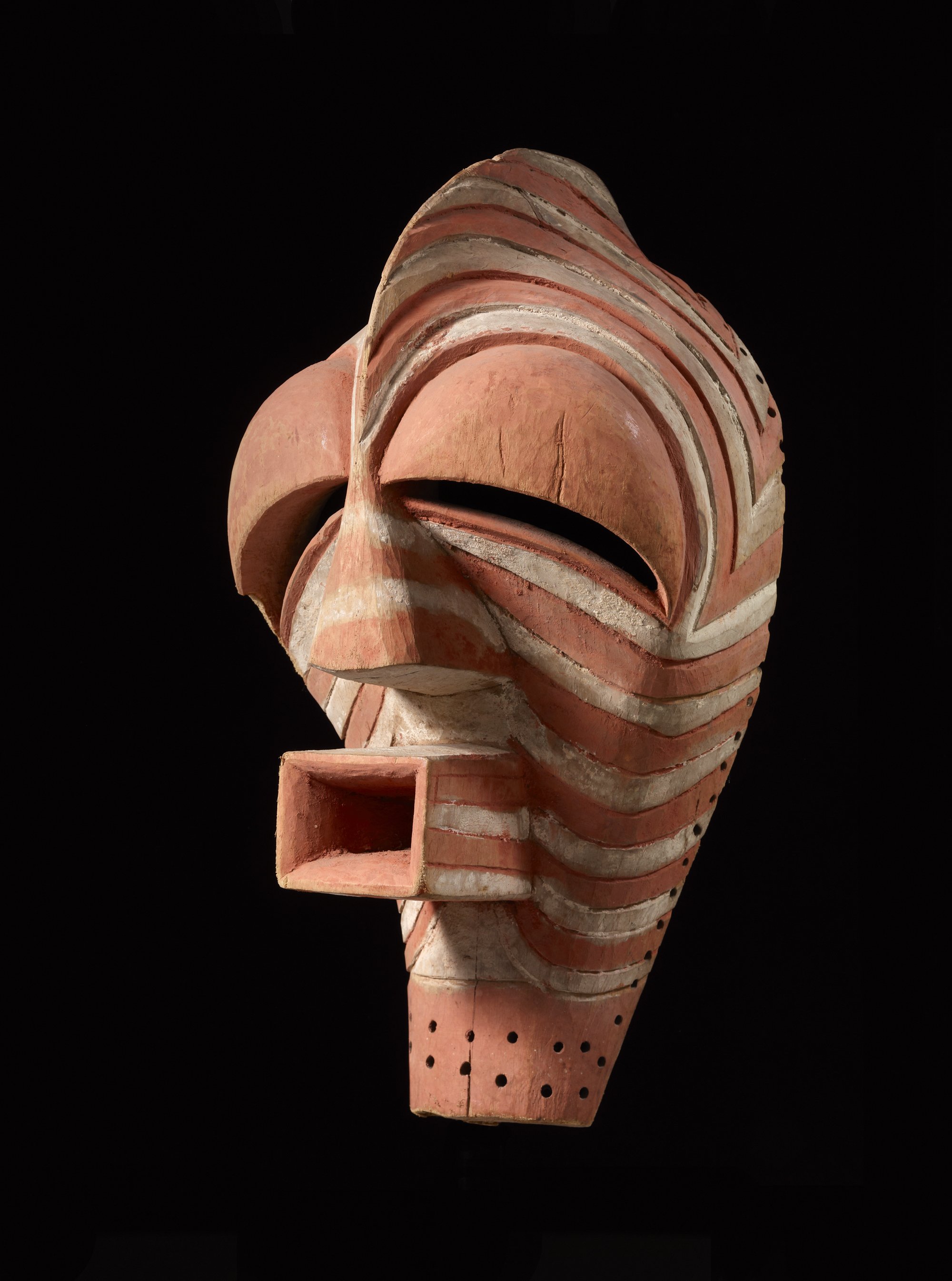

Albert Lutz: When growing our holdings, a priority is given to enlarge the existent collections. Either filling a gap or enlarging it thematically, or geographically. For example, not long ago we have tried to get hold of a piece that initially belonged to the collection of German ethnologist Hans Himmelheber and then passed down to Marceau Rivière, whose collection went under the hammer at Sotheby’s in Paris last summer. In fact, we already have an important collection of Himmelheber since his heirs gave us over 15,000 of his photographs, 750 objects and writings that he took back from Africa until the 70s.

Esther Tisa Francini: Himmelheber travelled through West and Central African 14 times as a scientist, ethnologist and collector who made acquisitions for himself and his customers: private collectors, and many museums. During that time he put together a work of documentation that is extraordinary: he would meet and interview the artists, such as carvers and casters in their workshops, taking them out from their anonymity. And this founds the base for a new history of African art.

Which was the object that belonged to Himmelheber in the Marceau Rivière’s auction?

Albert Lutz: The Baule oracle, a divination box with an anthropomorphic figure carved on its side. But it was sold for more than the estimate and we couldn’t go so high. The provenance was in this case crystal clear thus a reason of interest for us; but in other cases, before an acquisition, we do everything to ensure that the offered object comes from a legitimate source.

In regard to art restitution issues, Museum Rietberg

has been a pioneer in the research on provenance, hasn’t it?

Albert Lutz: I pushed for the museum to put efforts into the documentation of works, not only the new acquisitions but also the pre-existent holdings. In order to prevent art restitution issues this includes, whenever possible, the verification of their origins and of the artists who made them. It means that the history of the object should encompass the description of the circumstances in which it was produced, sold and how it later entered Rietberg’s collection.

Best practice in art restitution.

Following Macron’s speech in Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso) on December 2017 – when he declared his intention to return important artefacts to Africa – the public debate on art restitution has become very lively.

Esther Tisa Francini: Yes indeed; but for us it has started even before the debate on colonial art inflamed. Our research on provenance took off 10 years ago and it was 10 years after the signing of the Washington Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art focusing on pieces we acquired after 1933. It was the reappraisal of Eduard von der Heydt’s acquisitions that started it all here. We found that four Chinese pieces acquired by the Baron in 1935 were confiscated during the Nazi period; we immediately searched for their heirs and contacted them. It turned out that they were not interested in having them back. At that point we sought external expert opinions from in order to have an estimate of their value and pay back the family, while the pieces are still with us. (in regards with the Nazi period you may like to read our writing about agent Rodolfo Siviero, here is the link).

The Benin Royal Museum in Nigeria is due to be completed by 2021 and the reclamation of several artefacts from the country has grown in the last decade. Are you dealing with some art restitution requests?

Esther Tisa Francini: The request arrived to museums having the largest collections. But we have conducted independently researches on that side too. Three of the sixteen artworks from Benin in the Museum Rietberg can be traced back to the looting of the royal palace in Benin City – what is known as “punitive expedition”. One is a hip mask that bears a number from London dealer William Webster, a key figure in placing the plundered goods on the market in Europe. An ivory tusk had an invoice accompanying the sale stating the note “from the period 1897”, the year of the retaliation. And a second ivory carving in the form of bracelet we found belonged to the collection of general Harry Rawson, one of those responsible for the punitive expedition.

There are different opinions on restitution. Stéphane Martin, director at the Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, claimed for example that he prefers circulation of collections over restitution. What is you advise on this regard?

Albert Lutz: The issue of art restitution raises questions and it requires that each case is to be examined individually. Both art restitution and long term loans should be considered, but we need to be aware that these represent only a part of the process of making amends of historical injustices and not necessarily the most suitable solutions. An international dialogue is essential, possibly founding basis for a trans-cultural cooperation. In fact, we should not lose sight of the wider scope: knowledge production is a collaborative process.

Esther Tisa Francini: It’s important to guarantee transparency. Research on provenance might have become the new norm internationally in museums now, but that wasn’t the case when we started 10 years ago. It is a relatively new matter and a lot of research still needs to be done. On our side, we opened our storage 10 years ago already as an opportunity not just for scholars, but for anyone who is interested to see what we have at any time (except for photographs, painitngs and textiles that due to conservation reasons can’t be on permanent display). We then started to put the collection online, which is now largely accessible from anywhere in the world, also with provenances.

With the exhibition “Last Stop Nirvana” last year, you have proven that art can be an extraordinary diplomatic tool.

Albert Lutz: Well, in that instace we had the opportunity to host the sculpture of a standing Buddha from the Peshawar Museum and a delegation from Pakistan. We are the only museum that has signed with the Asian country a memorandum of understanding as a framework for future institutional co-operation that will give us the chance to invite Pakistani artists. But we always try to build bridges and promote cooperation with countries of origin, especially in relation to the conservation of cultural artefacts, documentation and research, as well as to knowledge sharing. For the current exhibition “Congo as Fiction” (on view until March 2020) – that also presents objects and photographs that Hans Himmelheber collected during his field trip to Congo in 1938–39 – we involved fifteen artists from Congo: and this also goes back to the idea of shifting perspectives.

Mr Lutz, what did you enjoy the most of your experience at the Museum Rietberg?

Albert Lutz: Since the very beginning as a curator of the Chinese department I had the chance to be involved in the decision making of all the other departments. And in these many years I was lucky enough to meet people from all over the world. That was the most enriching experience.

November 17, 2022