Emerging artists to watch: Kaoru Arima and his facial (un)recognition

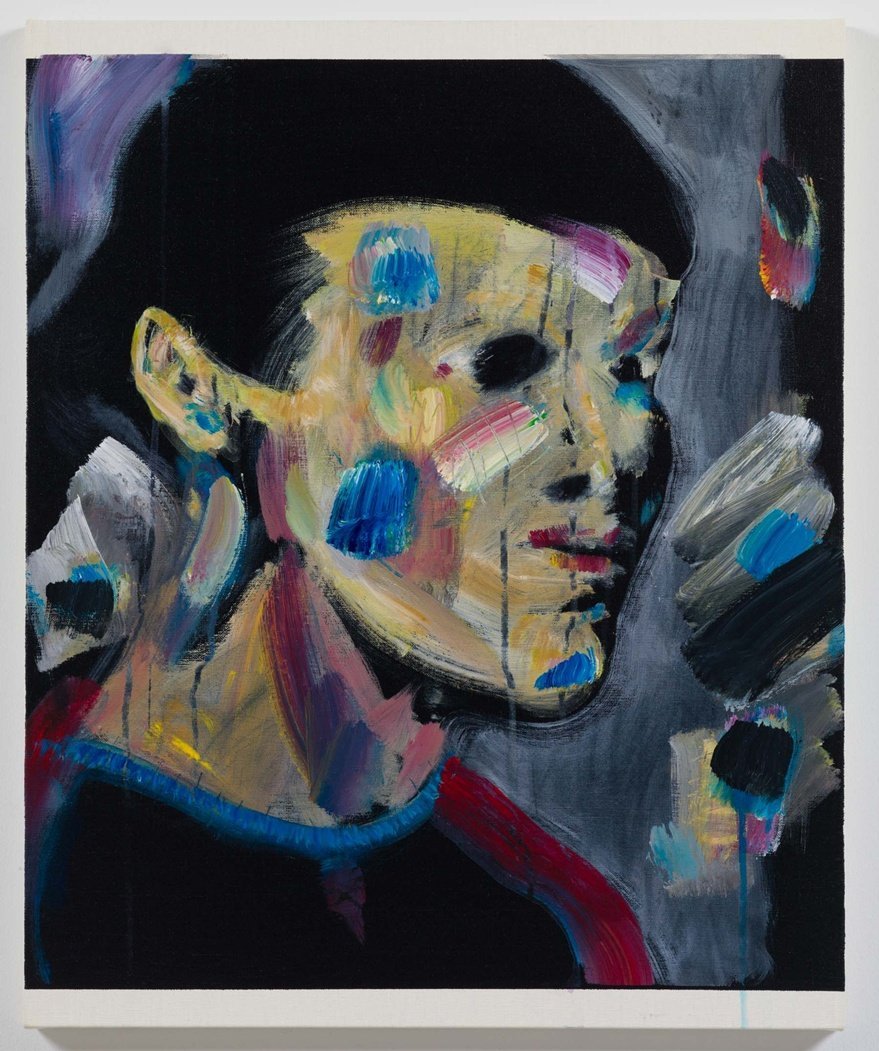

Kaoru Arima’s pictures of faces are paintings for an alternative, straightforward portraiture: romanticism no more; agendas no more; ego no more.

Kaoru Arima has been active as an artist for decades, but he is a present-day portrait artist. Based in Ishinomaki, Japan, he has been painting faces regularly with no apparent romanticism, which is rare in the history of portraiture. His portraits have a dry straightforwardness in them, a transparency that leaves no room for spurious intention.

When we speak about romanticism in this article, we don’t mean cliché: no bunch of roses; no self-destructive poets; no waves epically hitting steep cliffs. The romanticism in portraiture is instead allegorical. From 18th century sublime depictions of rulers to contemporary dystopian mapping of every face, from the hero to the zero, portraits have often been standing for greater, romantic visions, carrying nightmares with them just as often. Kaoru Arima keeps away from those evils, adjusting the scale of portraiture to the human, a task for the portrait artist that was often lost in ambition.

[Check our article about romanticism in self-portraiture here, or our interview with Nicolas Party here for more straightforward portraiture. Ed.]

Human, not that Human

Ironically, portraiture has been rather unhuman. The depiction of persons has rarely been about depicting persons. The lack of agendas in Kaoru Arima’s portraits is refreshing precisely for this reason. Portraiture has generally burdened its subjects with unwanted stories. This is the approach of those artists who have depicted human faces in order for them to do something else, from putting forward scientific arguments to political propaganda. Not Kaoru Arima.

One can think of Darwin’s study of facial expressions in his semi-forgotten 1872 book The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, for which the English biologist borrowed the portraits of G.-B. Duchenne de Boulogne: depictions of expressions rather than depictions of people, exploiting portraiture for the sake of science.

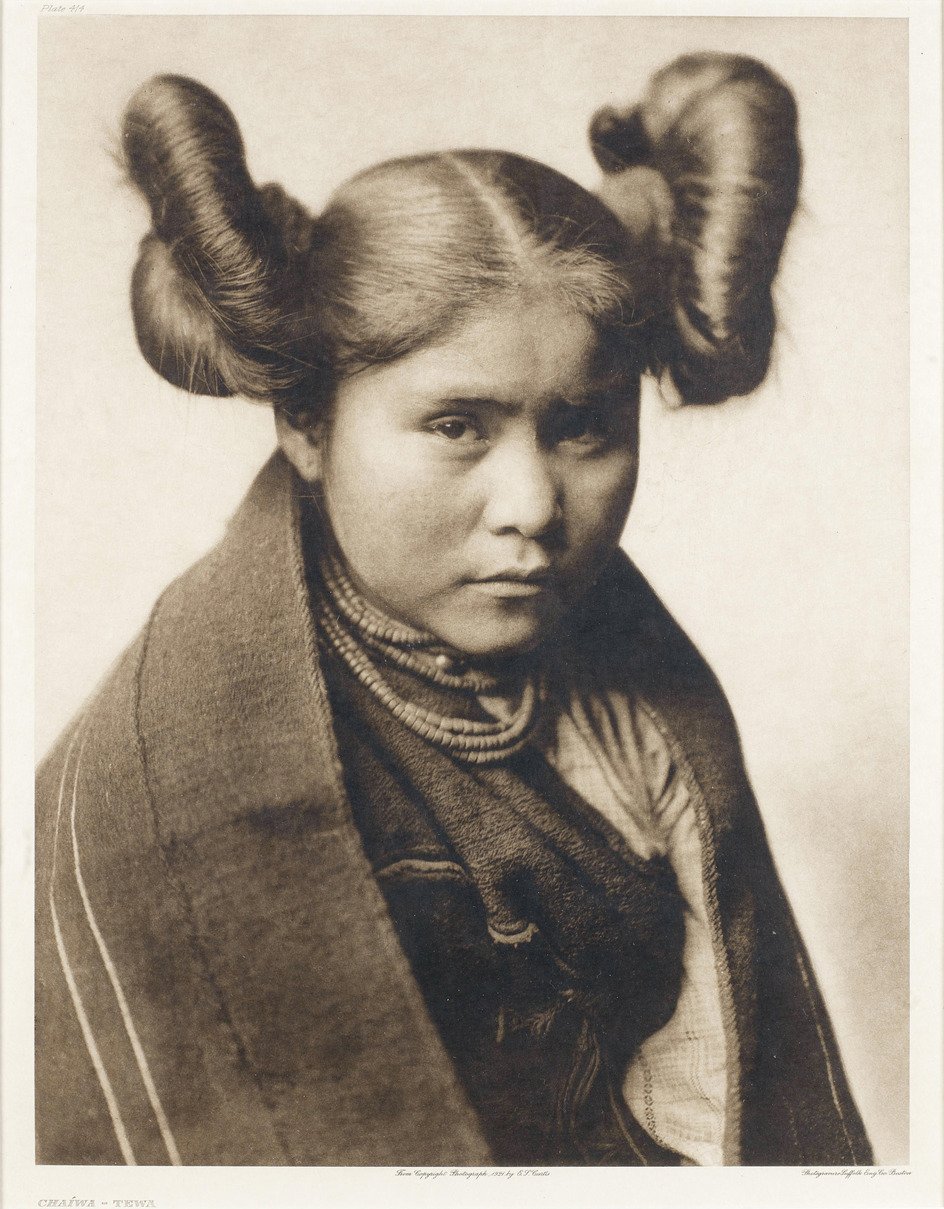

On a more politicized level, colonial photographers such as Edward S. Curtis used portraits as tools to build their own story rather than respecting the subjects. His depictions of indigenous Americans as “noble savages” are problematic insofar as they are not honest representations of them.

Cataloguing has been another task of portraiture. For example, one can think of August Sander’s records of early 20th century German social classes; or Gerhard Richter’s 48 portraits of historical figures for the 1972 Venice Biennale. None of this portraiture has so much to do with representing people as it does with sending messages. Again, this is not the case of Kaoru Arima.

So Romantic

Coming back to romanticism at large, painting has also exploited the images of persons for various epics. What would Napoleon be without his ramping horse painted by David? How about Picasso, whose famous answer “it will” when asked why his picture of Gertrude Stein didn’t look real enlarged his ego more than his portraiture? One can see how this has little to do with picturing faces.

The task of simplicity isn’t at all simple, and portrait artists haven’t been good at it. The harder the task, the bigger the merit, which is why Kaoru Arima is exciting. We agree with Forrest Nash when he says that his portraits make us detect the glow a human face emanates despite the visual noise there might be around it. In fact, we believe this is precisely achieved through the lack of agenda in his portraiture.

Changing the Subject

Lack of agenda for the portraiture artist doesn’t imply lack of content and consequent boredom. What happens in the art of Kaoru Arima is instead a change in the subject, not so much as misrepresentation as subtle transformation instead. There is a switch from honest facial rendering into something else, precisely because the facial rendering isn’t about something else. Says the artist about his process:

I gain inspiration from figures in fashion magazines and start making portrait paintings from there. However, this first image is not yet an artwork, so I paint another portrait over the initial one until the human face becomes a form of landscape.

How many brushstrokes does it take to turn a face into a space? What is that ingredient that makes a portrait taste like a vista? It surely need not be political, scientific, or even romantic intention. Formal choices of the painter are key, with European art historical techniques of oil painting on canvas properly appropriated, yet stripped of their dusty intellectual schemes. If formalism as a theory of art (Clive Bell’s to be precise) were to come back, it would find a safe haven in Kaoru Arima’s studio.

Panorama

This idea of enlarging an otherwise very human portrait to an image of a landscape is best understood in the larger context of Kaoru Arima’s practice, which goes beyond portraiture via different formats, techniques and media. Examples are his recent solo exhibitions at Misako & Rosen, Queer Thoughts, and Édouard Montassut. For his pictures, the rather mysterious formal choice of not painting the top and bottom of the portrait is explained in terms of cropping and landscaping used in his non-portrait drawings. Says the artist:

In the beginning, I was drawing on canvas but when my personal finances dwindled, I started to use cheaper paper, like free newspapers or coarse blank paper (now standard copy paper is cheaper). I am still using newspapers because I realized that they include so many kinds of relationships and social matters. This confuses people about the borders between the artwork and its support. Where does one begin, where does the other end? When artworks are photographed for the purpose of documentation, typically the whole space of the work is reproduced; but my drawings are most often reproduced only with the drawn/painted area. This always excites me. It influenced my portrait works, where I don’t paint the top and bottom of the canvas.

Coming back to the dry straightforwardness mentioned above, it is fascinating to see how mere material constraints result in powerful aesthetic experiences that don’t need second thoughts: no romanticism makes portraiture so incorrupt, no further intention. Effective forms, simple economics, and chancy cropping do. The cleanness of Kaoru Arima’s faces is like that of lungs exhaling after a nasty yoga pose, pleasure made simple.

June 13, 2020