Not afraid of craft: the Van der Kelen Logelain school of decorative painting

We feature the Van der Kelen Logelain school of decorative painting in Brussels, a recognized springboard for important contemporary and applied artists.

The complex relationship between ancient and contemporary art finds clarity in the equally complex relationship between art and craft. 20th century deskilling and dematerialization are highlighted by their opposites from both the past and the present; the manually skilled old master meets the emerging one using traditional techniques. One side feeds the other. Yet instead of philosophical dissertations starting with the corny aphorism “Duchamp was also a skilled painter,” we aim at hinting at the issues above by telling the story of the Van der Kelen Logelain school of decorative painting in Brussels. As we will see, it is one of the few applied art schools popular with contemporary artists too.

[Here is a previous analysis of traditional techniques in contemporary art. Ed.]

Starting as two separate schools in 1882 and 1892, the current Van der Kelen Logelain is the merge of the two experiences and the sum of the two traditions. It currently offers a single trainingship of six months, which for many students consists of six tough months of working seven days a week for 12 hours a day. Knowledge never comes easy, but at the Van der Kelen Logelain there is a quasi-religious sense of necessary pain or sacrifice to gain the precious gift of technical skills. For those who know about training in classical music or dance, the Van der Kelen Logelain might feel familiar.

In order to paint a clearer picture of the school as well as indirectly heating the art vs craft debate, we heard from both students and teachers. We first met Sylvie and Denise Van der Kelen, offsprings of the founders and directors of the school, who explained about the patterns each student needs to practice to learn the over 60 techniques for the imitation of woods and marbles. We learned that despite being rooted in tradition, this catalogue of patterns is constantly updated. Says Sylvie Van der Kelen:

Each year we work with one designer to create a new model with new forms of presentation, as looking at our old panels we feel the influence of the 19th century and of each decade in the 20th century. We need to carry on trying to work with our time. We tell the students that decoration work goes back more than 3000 years before Christ, it is constantly evolving, it doesn’t stop. New types are born, new materials become fashionable.

New forms might be the access point for art to enter the school, and Sylvie Van der Kelen herself has recently collaborated with artists and architects on the creation of new designs for sculptural pieces. Moreover, younger generations of students bring new inputs, pushing the border between decoration and art through tradition. The age limit of the school (max 50 years old) is only partially related to this issue however. The tough workload of the class and the physicality necessary to work in awkward places such as high ceilings also play a role. As to the gender balance, she says:

At the beginning of the school there were only men enrolled. The first woman came only after WWII. It was equally split during the 80s and 90s, and after a period of mostly women, it now begins again to be more balanced. Backgrounds are also very different. Mostly house painters came here at the beginning, just to get an upgrade for their work. During the 80s there were many girls from rich families, and now it is more diverse: still some house painters, but also architects, artists, restorers. Generally we find that more and more educated people want to work with their hands. After long academic studies, they want to learn manual skills.

Contemporary Art

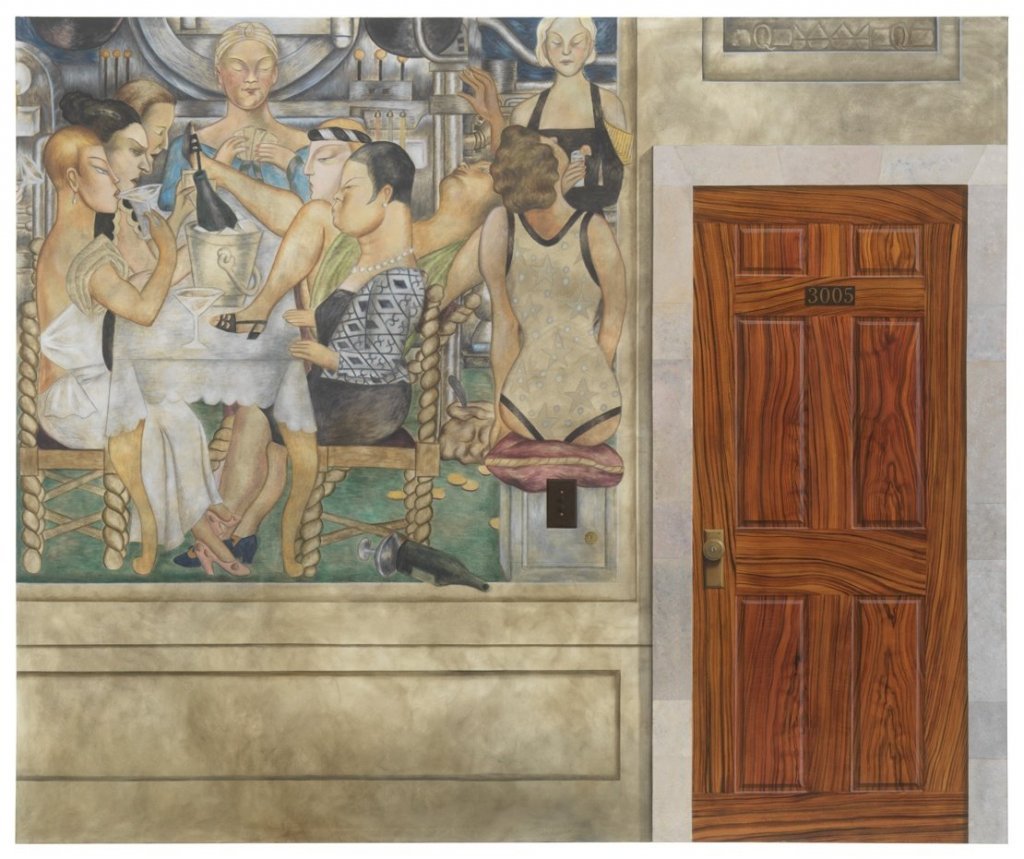

Arguably, if the art world has heard of the Van der Kelen Logelain school, it is thanks to Lucy McKenzie. [Here is our interview with Lucy McKenzie. Ed.] The Brussels-based, Scottish artist was a student there about ten years ago, and as we will see she has inspired others from the field to attend the school. Her decision came from a stall in her practice, and we asked her how the Van der Kelen Logelain helped moving forward:

At that time I had already settled into a regular rhythm of gallery exhibitions and institutional shows with self-organised projects in between. While I felt very lucky to have these opportunities, continuing like that felt like coasting along, frictionless, if nothing disrupted it from outside – a bit like the fashion calendar: routine. Also I’d reached the limits of my knowledge and skills in decorative painting and knew I wanted to be able to inhabit that style, not just reference it in a slapdash ‘artistic’ way. Since studying I have continued the rhythm of showing that I had before, but now that I am able to push my painting so much further these shows feel like much more valuable opportunities, moments to emerge from the studio and crystallise something.

Many if not most contemporary artists would subcontract highly skilled work as the one taught at the Van der Kelen Logelain, but not McKenzie. Many reasons can be there to go against the grain in such a way, the most important being the pleasure found in manually crafting something for yourself. In the case of McKenzie, her research into manual artistic labour is mostly involved in the decision. She says:

I don’t have an issue with artists subcontracting, I do it too. I just think the hierarchical structure that guides that relationship is worth examining – because I do not place art on a higher artistic plane than the applied arts. I run a fashion label with my friend Beca Lipscombe (Atelier E.B) where everything is subcontracted to manufacturers and all those processes and relationships have to be negotiated.

Learning a skill and undertaking personally the labour that many artists in my position would outsource was definitely an intentional statement. But these days I outsource that painting work more and more – because what I actually thrive on is discovery and learning, not just labour for its own sake as a proof of value – I came to understand that also as a trap. So I learn and move on, adapt and cross reference. Over the lockdown I’ve been learning to make bobbin lace from a teach yourself guide – I’m interested in structures and processes. I’m also trying to get my head around Romance fiction, its formulas and ecosystem. When I look at something I find curious, knowing how it is made means I can appreciate it even more. With the bobbin lace I wanted to know, when I looked at a piece of lace, just how much work goes into it, fully appreciate what makes it special – and to do that I need to try it myself.

Back to the Van der Kelen Logelain, the point of view of the contemporary artist on her experience speaks about labour efficiency and tradition, which for better or worse are rarely touched topics in contemporary art education:

[During my studies at the Van der Kelen Logelain] I learned a lot about capacity for work and what to demand of yourself, discipline, analysis. I learned lots of practical things about working with traditional materials and tools, preparing surfaces, efficiency, etc. How to use time as a tool. But the most remarkable thing I learned at the school was the techniques – they have been honed and perfected over so many years, incredible knowledge of materials, tools and methods. A proper education. This school should be Unesco protected!

Applied Art

We also spoke to former students who decided to pursue a career as decorative painters. The Milan and London-based Studio Pettirosso is the firm of Beatrice Girardi Boschetti, Valentina Bonato and Cristina Perletti. They all studied at the Van der Kelen Logelain yet not at the same time. Girardi Boschetti was the first who heard about the school and decided to enrol after she saw a fake marbled surface in a worksite of her mother’s architecture studio. Coming from humanities, she had no previous experience and yet learned quickly. Her two colleagues followed and attended the school a few years later, struck by her work. Their studio now focuses on decoration, restoration and installation.

When asked about the differences between painting education in Italy and at the Van der Kelen Logelain, Girardi Boschetti mentions the use of oil paint in the Belgian tradition vs water-based paint of the Italian one. The realism and intensity of the former doesn’t compare to the latter they say, yet the members of the studio all confirm that techniques need to be adapted to the architectural context. There is not an ever-winning solution.

Studio Pettirosso does not only do decoration though. They have been taking the role of contractors for contemporary artists, those manual labourers McKenzie refers to just a few lines above. Their work for Francesco Vezzoli stands out and recently they have been busy with giving new life to Gio Ponti’s Casa di Fantasia, sold at auction a few months ago and now in need of fabrication. This will leave space for an interpretation of the piece too. Concerning the relationship with contemporary artists, say the members of Studio Pettirosso:

Working with a contemporary artist is something different. It is very inspiring because it forces you to challenge yourself and to push yourself harder in order to give life to their ideas. Our traditional techniques are a necessary starting point which need to be modernised and adapted to the artist’s needs. A good command of old techniques is fundamental for interpreting the artist’s ideas and for bringing them to life. Vezzoli is at the moment the only contemporary living artist we’ve had the chance to work with for ongoing projects. It was a blessing getting in touch with him as his ideas are just amazing and he always pushes us forward in trying to realise his visions. Until now it has always worked great. Nonetheless this happens with any client, not just the artists. A “conventional” client would ask to rethink their house walls or ceilings looking for decorative painting and it’s still very important to create a “contact” and try to understand their feelings and their taste, which sometimes might be different from ours. So we can say every job pushes us harder to find a perfect fit to the clients’ requests. Some examples are a mirror we made to be fitted above a black Baroque Belgian marble fireplace, Lazard’s bathroom in Milan or a Klimt reproduction fitted into a shower…

Applied Art and Contemporary Art

Lastly we spoke to Swiss artist Sarah Margnetti, also based in Brussels and a student at the Van der Kelen Logelain in 2015-16. She told us she knew about the school because she was looking for a way to have a sustainable job related to painting aside her own practice. She learned about the work of Lucy McKenzie during her master and it sparked her interest in the Van der Kelen Logelain again. Her experience at the school also matches with what we heard from others: the intensity of the short program teaches techniques and discipline at once. Margnetti mentions that because of the school she is no longer afraid of exhausting, large scale paint jobs: if you learn to paint non-stop for six months, you can probably do it for one month too.

Her practice is now divided between her own artistic production and work for famous contemporary artists such as Nicolas Party or Haris Epaminonda. For Party for example, she is responsible for many of the large environments of fake materials and decoration in which his paintings are often found. Interestingly, Margnetti doesn’t seem to value her own practice as a contemporary artist any more than the intensive, commissioned work she does for others. In fact, our chat with her reminded us that art has been a collective effort for much longer than it has been driven by a concept of authorship–think of Medieval painter workshops with dozens of assistants.

Back to the art vs craft debate, our visit to the Van der Kelen Logelain school and the exchanges we had afterwards helped us to confirm that neither of these two concepts is mutually exclusive. It might no longer be the time of dematerialization and deskilling, though it seems we are not praising the hand virtuoso again. It is no longer the contemporary art discourse of the 1970s or 1990s, but it is not the 18th century again either. Criticality lives in this fertile middle ground today.

June 30, 2020