Sandro Botticelli: portraiture as a lost paradise

Botticelli’s portraits bring us to the golden age of his life, preluding his dramatic fall into debts and oblivion.

In 1667 the poet John Milton wrote long verses describing the Biblical expulsion from Eden and the consequent fall into despair. Moved by exoticism, many artists pursued the dark dream of finding this impossible heaven far from their home. Not Botticelli, who left his lost paradise in his city of Florence at the age of 47, fabricating an Eden of heavenly portrayed characters.

The rise and fall; the golden years and the decline; good and bad luck; loss of work and spiritual crisis: the year 1492 is Botticelli’s pivotal moment. Before was the triumph of his new style; after was the painful downturn that would leave him forgotten by his contemporaries.

In 1492 Botticelli must have felt fears rising at the announcement of Lorenzo the Magnificent’s death. Those days, popular imagination thought that the end of the world would come with the end of Lorenzo. In his Florentine Diary, the chronicler Luca Landucci reported images worthy of a painting by Hieronymus Bosch. He said that just before Lorenzo’s death a comet had appeared in the sky and wolves had been heard howling; in the church of Santa Maria Novella, an enraged woman had started shouting that an ox with horns of fire was setting the whole city ablaze; lions had been seen fighting among themselves in the streets of Florence; finally, lightning struck against the lantern of the dome of Santa Reparata, causing large stones to roll in the direction of the Medici house.

Landucci even wrote that the most famous doctor in Italy, Lorenzo’s personal doctor Piero Lioni da Spoleto had thrown himself into a well out of desperation and drowned – although someone claimed that he had instead been thrown into the well on purpose as a punishment for failing to save his famous patient.

These episodes give the sense of panic felt by an entire city. Yet for Botticelli the mourning was double. His fortune as a painter was inextricably linked to the de Medici family: patrons, collectors, clients of his most sophisticated works, often sending commissions from other friendly families. A phase of slow personal decline would also begin in 1492, lasting almost twenty years and marked by illness, debts and doubts.

Botticelli’s golden age was between the mid 1470s and the 1490s: a season of great commissions and awards, the years of Primavera and the Birth of Venus, the years of the mature style finally freed from the apprenticeship in the workshop of Filippo Lippi. Those decades were also marked by large portraits, a genre that greatly interested the artist. At the time, he was increasingly showing indifference, if not impatience for religious subjects. His Portrait of a Young Man holding a Roundel dates back to this period. The work is now being auctioned at Sotheby’s with an estimate of more than 80 million dollars and with the hope of adding the painting to the record prices of the Portrait of Doctor Gachet by Van Gogh or the Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer II by Gustav Klimt.

The painting has an undertone of twentieth-century magic realism à la Antonio Donghi, the most Renaissance of Italian painters of the last century. It depicts a young man with his haircut in the Florentine fashion of the 1480s. He holds a medallion of a saint, probably Saint Peter or Saint John: an original insert, perhaps a fourteenth-century work by the painter Bartolomeo Bulgarini.

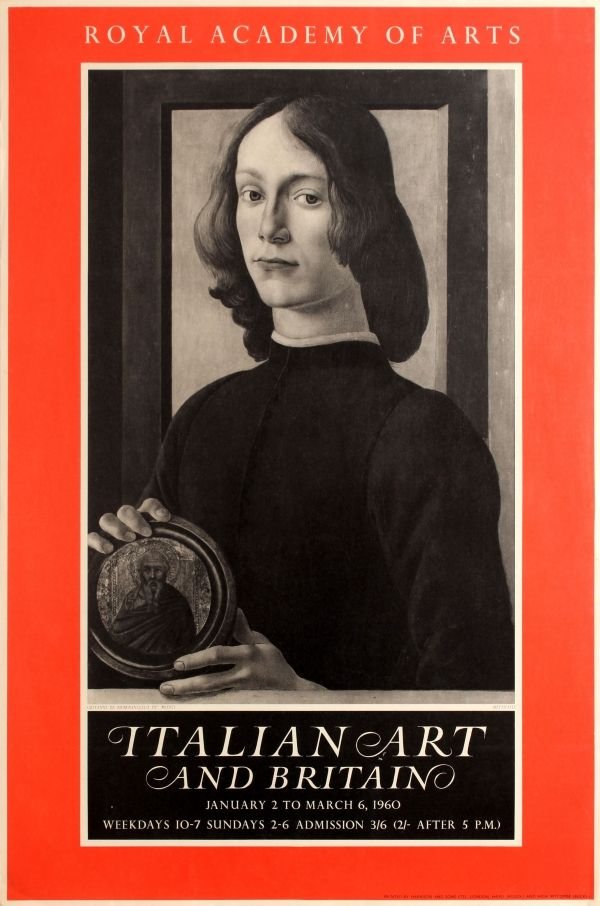

Those who went to the Italian Art and Britain exhibition at the Royal Academy in London in 1960 saw the young man standing out in black and white in the posters. The painting was included in Botticelli’s catalog already, attributed with some reservation in 1941 when Sir Thomas Merton bought it from the art dealer Frank Sabin. It ended up at auction and was purchased by tycoon Sheldon Solow a few years later. The painting is not unknown to the public: it has been exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, at the National Gallery in London and at the Städel Museum in Frankfurt.

Its layout resembles that of the Portrait of a Man with a Medal of Cosimo the Elder now at the Uffizi. Here too there is a tondo in the hands of a young man: a reproduction of the commemorative medal of Cosimo the Elder, minted in bronze between 1465 and 1469 whose copies are still visible today at the Bargello Museum in Florence. The work can be dated around 1475. The Medici’s propaganda and their political campaign exploiting the figure of the pater patriae Cosimo recruited the best artists and intellectuals – the same medal minted by Francesco Rosselli was reproduced on the title page of Marsilio Ficino’s Epistolarium. The identity of the subject in the portrait is unfortunately unknown, and so is that of the young man in the Portrait of a Young Man holding a Medallion. Most likely they were influential supporters of the Medici dynasty.

References to the Medici in Botticelli’s works were almost obligatory in the 1470s and 1480s. Once he left the workshop of Lippi, Botticelli’s career heavily depended on the powerful family. His first known work, the Sant’Ambrogio Altarpiece depicts the Medici patrons Cosma and Damiano kneeling as saints. Lorenzo would later commission Botticelli’s best-known masterpiece La Primavera. It was him who told his younger cousins to purchase it. It was still him who recommended the artist to the Pope so that Botticelli could work on the Sistine Chapel in Rome, intervening well before Michelangelo’s Judgment would cover the simple starry sky painted earlier by Piermatteo D’Amelia.

The Medici also sent some real hot potatoes to the artist. In 1478 Botticelli had to work on the portraits of the hanged, the killed perpetrators of the Pazzi conspiracy painted on the door of the Dogana of the Palazzo della Signoria. Removed in 1494 after the expulsion of the Medici from the city, what remains today is the portrait of the unfortunate Giuliano, killed by the Pazzi and painted in at least three versions between 1478 and 1480. These are now held at the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin, the National Gallery in Washington, and the Accademia Carrara in Bergamo. They have similar formal features compared to other portraits by Botticelli: a sober background, rendered geometrically, sometimes showing an open door or window that remind of the 20th century metafisica paintings.

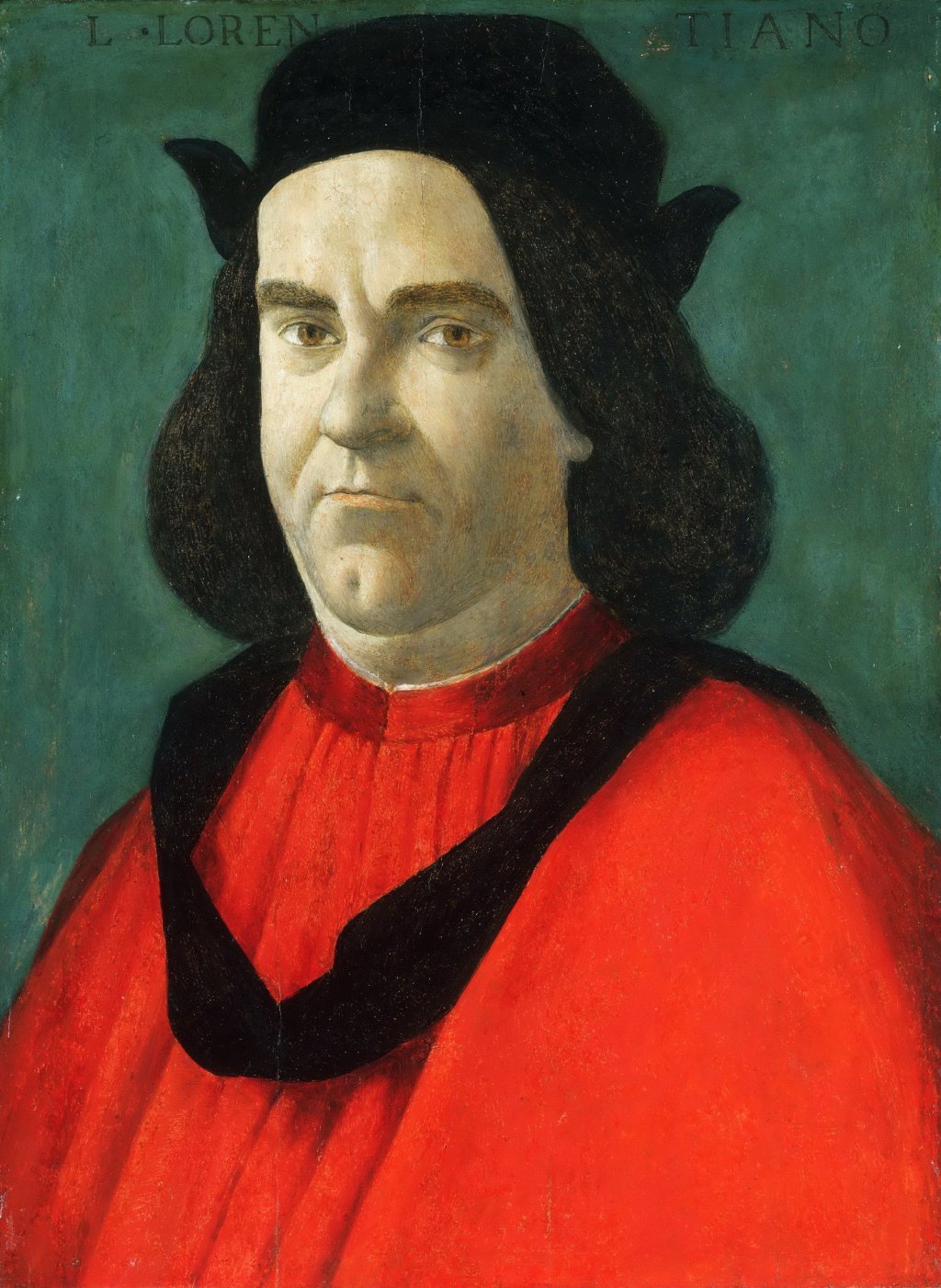

A few years earlier Botticelli portrayed Lorenzo the Magnificent himself, inserting him in the Adoration of the Magi of 1475 now at the Uffizi. Wearing red and black, Lorenzo is at the center of the group of characters on the right. The artist’s special taste for portraiture is exhibited in every character: the Magi are depicted as the late Medici family members (Cosimo the Elder, Piero the Gouty and Giovanni), along with the living Lorenzo and Giuliano. Botticelli also portrayed himself in this very elegant squad celebrating the birth of Jesus. Wearing a yellow cloak, he stares at the viewer with proud eyes.

Recognizable faces in non-portraiture pictures were fairly common at the time. Botticelli’s St. Sebastian from 1474, commissioned to ward off the plague and modelled on Pollaiolo’s style almost certainly depicts Giuliano. After all, the 1470s and 1480s were fruitful decades for portraiture in Florence, not only in painting. Think of the Lady with a Bouquet (1475-76) by Andrea del Verrocchio now at the Bargello Museum or the Portrait of Ginevra de ‘Benci (1474-78) by Leonardo now at the National Gallery of Art in Washington.

[Here is our analysis on the workshop of Verrochio. Ed.]

Sandro Botticelli, “Portrait of a Young Woman” (possibly Simonetta Vespucci), ca. 1480, 82 × 54 cm, tempera on wood, Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main, Germany

Sandro Botticelli, “Spring” (detail), ca. 1482. 203 × 314 cm, tempera on canvas, Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy

Sandro Botticelli, “Birth of Venus” (detail), ca. 1485, 172.5 × 278.5 cm, tempera on canvas, Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy

Sandro Botticelli, “Portrait of a Young Woman” (possibly Simonetta Vespucci), ca. 1480, 55 × 43 cm, tempera on wood, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin, Germany

Sandro Botticelli, “Portrait of Esmeralda Brandini”, ca. 1470-1475, 65.7 x 41 cm, tempera on wood, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, United Kingdom,

Sandro Botticelli, “Portrait of a Young Man”, c. 1469, 51 x 33 cm, tempera on wood, Palatine Gallery of Palazzo Pitti, Florence

Sandro Botticelli, “Portrait of Michele Marullo Tarcaniota”, c. 1496–1497, 49 × 35 cm, tempera and oil on panel, transferred to canvas, Guardans-Cambó Collection, Barcelona (on loan to the Prado Museum, Madrid)

Sandro Botticelli, “Portrait of Lorenzo by Ser Piero Lorenzi”, c. 1490–1495, 50 × 36.5 cm, tempera on wood, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, United States of America

Sandro Botticelli, “Pallas and the Centaur”, c. 1482, 207 × 148 cm, tempera on wood, Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy

Pictures with complex compositions followed this portraiture trend too, for example Botticelli’s Primavera and The Birth of Venus. The art historian Martina Corgnati has focused her attention on Venus in the background in the former (approx 1483) and on Venus as the protagonist in the latter (1482-85). Says Corgnati: “The first Venus looks sideways in our direction, apparently without a specific narrative reason to do so, while she should perhaps follow the first steps of her protected creature, just born from the somewhat forced embrace of the nymph Cloris by the lascivious Zephyr.”

Corgnati continues: “The gaze of the newborn Venus is similar, terribly provocative at the moment of her birth from the waters of the Cypriot sea. […] These gazes are direct, almost peremptory and made more evident by the clear irises on which the small but very black pupils point at us. They perfectly fit the fascinating bystander, who ‘hands’ us the image, inviting us to admire it and perhaps to discover its hidden meaning – a picture still so mysterious despite the many historical, critical and philological investigations.”

Corgnati points out that these figures are the active protagonists of the two paintings: “the divinities of the Roman era painted in Pompeii or Herculaneum were all closed and contained in their world, leaving the observer the task of winning their attention. Instead, the allegorical reinterpretations of the Florentine artist are here for us, to delight us, involve us, and teach us.”

The satisfaction of Botticelli in offering “paintings that look at us” is undeniable. In the portraits, the artist shows his concern with a sense of beauty that doesn’t have so much to do with reality as it does with ideals. The harmony of the composition follows this concern: the subtle drawing modulating the contours of the faces; the lines making the masses lighter; the abolition of tonal contrast; the almost disinterest in matters of space and perspective. The goal was a purified and rational beauty without drama, a conception of painting admired by Neoplatonic writers and philosophers from the circle of Lorenzo the Magnificent – but also by Lorenzo himself, who had been schooled in Neoplatonism by his tutors Gentile Becchi, Cristoforo Landino and Marsilio Ficino. The style of painting embraced by the artist reflected a vision of life and religion: the divine presence in humans, which are the mirror of the One and made up of eros.

Botticelli’s painting changed when these political and philosophical scenarios changed too. After Lorenzo’s death and the expulsion of his son Piero from Florence, the so-called cadetto branch of the Medici family returned to power. Among the new rulers was Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco, for whom Botticelli had painted the Primavera and the Birth of Venus but on the interest and advice of Lorenzo. The new Medici still trusted the painter with commissions, however the world was now different. Botticelli’s friendship with power was gone and so was that cultural climate that had informed so many of his works.

Soon would come the time of Savonarola, whose sermons reverberated in the Lamentation over the Dead Christ at the Alte Pinakothek in Munich: a work by Botticelli that is anything but Neoplatonic in its dramatic empathy and the representation of the friar’s gloominess. It was realized just three years after the death of Lorenzo the Magnificent. The first interest of Botticelli under the spell of Savonarola is no longer the beauty of the line. In the Mystic Crucifixion (1497-98) now at Harvard the words of Savonarola thunder in the stormy sky, from which lightning and fire are pouring. The Magdalene hugs the cross tightly and we can imagine so did the painter.

Botticelli was a man of humble origins, the son of a penniless leather tanner. Under the protection of Lorenzo the Magnificent he must have thought he was living in the best of all possible worlds. That paradise was now gone. Heaven only exists in nostalgia and hope: a dramatically distant elsewhere.

Bibliography

- P. H. Horne, “Alessandro Filipepi called S. B., painter of Florence”, Londra 1908

- W. Bode, “Sandro Botticelli”, Berlino 1921

- A. Schmarsow, “Sandro del Botticello”, Dresda 1923

- A. Venturi, “Botticelli”, Roma 1925

- A. Warburg, “Botticelli”, 1893, Milano 2003

- M. Corgnati, “I quadri che ci guardano. Opere in dialogo”, Bologna, 2011

- A. Cecchi, “Botticelli e l’età di Lorenzo il Magnifico”, Milano, 2007

June 16, 2021