Emerging artists to watch: Willa Wasserman

Willa Wasserman’s work is inscribed in the phantasmatic possibilities of painting, in between contemplation and rejection of tradition.

A ghost still to come: on Willa Wasserman’s painting

The question is indeed “whither?” Not only whence comes the ghost but first of all is it going to come back? Is it not already beginning to arrive and where is it going? What of the future? The future can only be for ghosts. And the past.

– Jacques Deridda

What is painting today? In order to answer we need to consider today’s technological context as well as contemporary questions of visibility. Politics involves a relationship with appearance, just as visibility is intertwined with the construction of identity. For this reason, painting today may seem an anachronistic act with no place. On the other hand, and despite the risk of its marketability, painting can also become a countermove.

Many artists of the last generations have locked themselves in their studio. Sheltered from the present, they have been working on canvas. Their practice oscillates between the appearance of a miracle and the unknown. After all, how to judge their medium of choice? How can we be objective or critical in the face of their work? What are the possibilities of critique facing a medium like painting today?

Willa Wasserman considers the haunted and ghostly nature of painting. On the skin of the canvas there is irony, criticality and a legacy of a history – at least for the West- based on the repetition of ruptures and negations. Wasserman’s work is inscribed in these phantasmatic possibilities of painting, considered in between contemplation and rejection of a certain tradition. Their works are a form of resistance, an operational absence erasing all security, both of tradition and disruption. Their painting is placed in the transition, in the possibility of adherence and convergence of different elements.

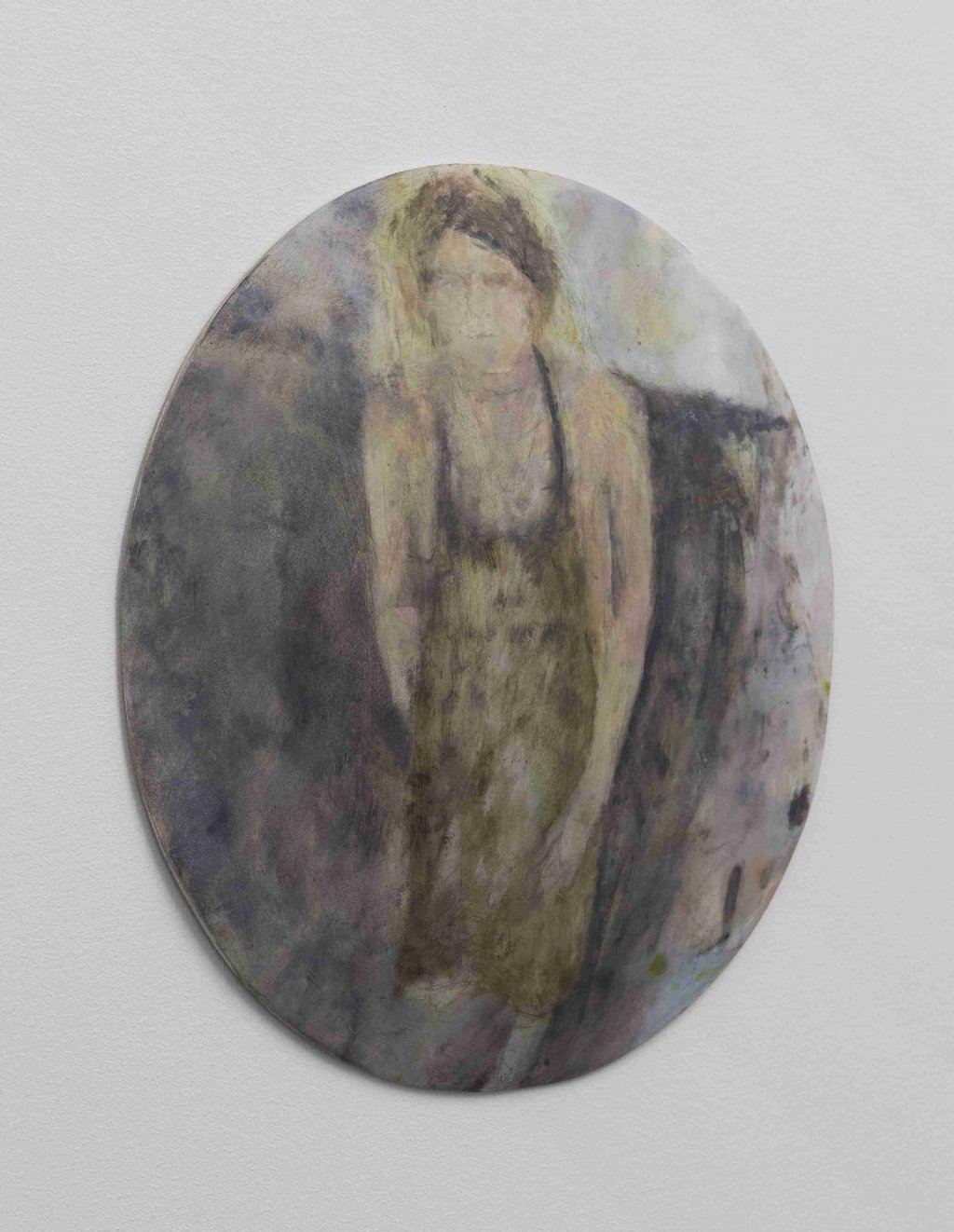

Willa Wasserman, Self portrait in a convex mirror, 2020. Courtesy of Good Weather and the artist.

Willa Wasserman, Self portrait in a convex mirror, 2020. Courtesy of Good Weather and the artist.

The transition occurs with and from the bodies, in the mixing of them with the space and in their possibility of crystallizing, even if only in a fleeting passage or in their temporary representation. This is seen in the works now at Good Weather, where starting from Muybridge’s photo studies on movement, the artist explores transitory poses such as steps or turns. These are different from what we see in the anatomy books of Muybridge. They are more than his constructions of races and genders in his chrono-photographs. The instability of poses contrasts the archetypes he tried to construct.

A transition and transformation also manifest in Willa Wasserman’s still life paintings of sunflowers. Illuminated by natural light at Good Weather gallery, they take up Christian metaphors with personal, intimate and secret meanings. The reciprocal and metamorphic tension between interior and exterior, personal and collective, acceptance and denial, is recorded in the work Self Portait in a Convex Mirror (2020), a portrait that reveals the condition of passage and identity mutation. This work again departs from Muybridge’s investigations and from Google Street images, an archive the artist also uses to explore instability. The body, the skin, and the aura of these moving figures rest on transitory surfaces, protected from immobility or fixity. It is the artist’s attempt to build an archive of mutability with their convex paintings.

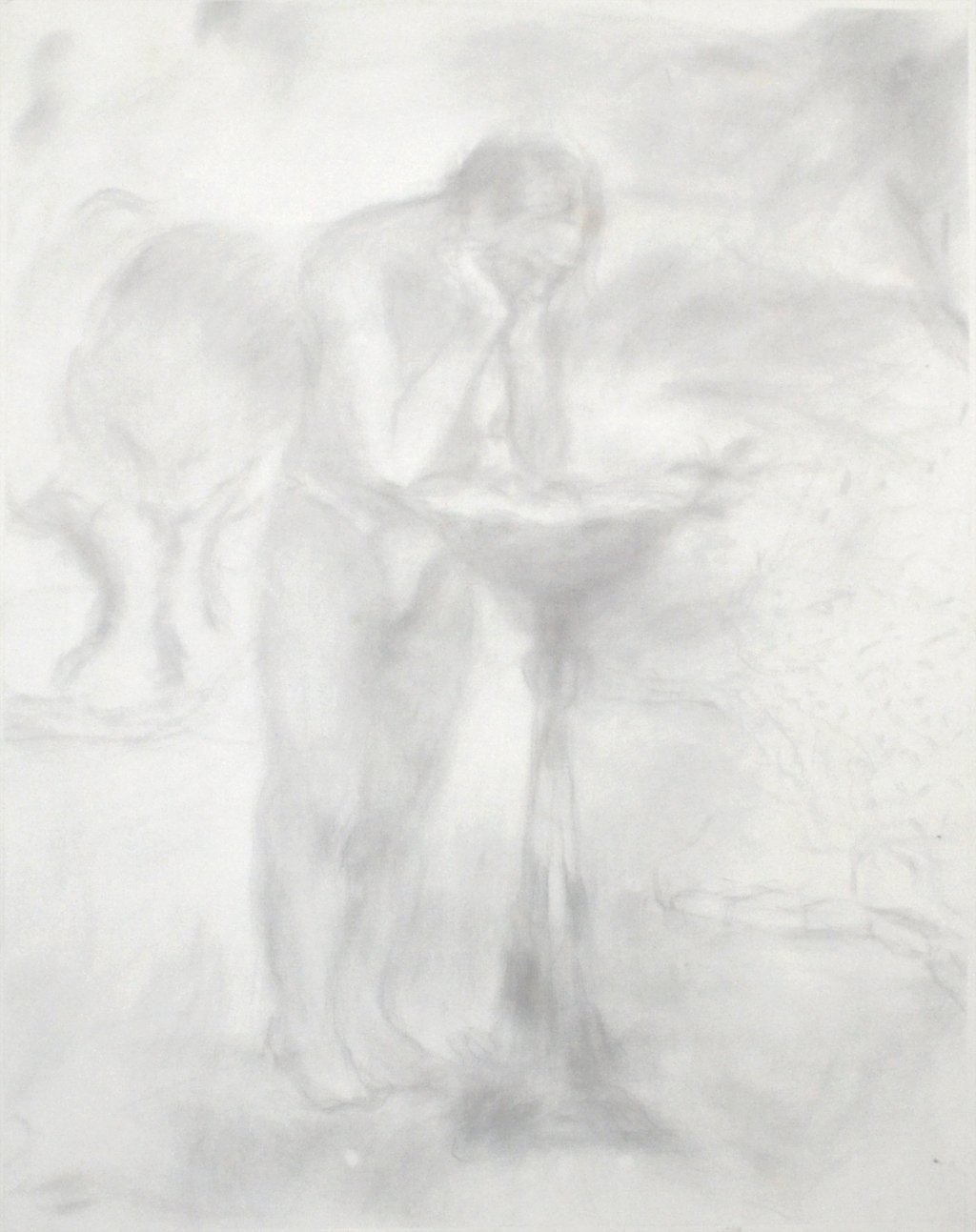

Their bodies on canvas are weak and vulnerable. Hidden, erased, imperceptible are the features of their (in)consistency. They are traces, marks on poplar wood or linen surfaces, materials that exercise a certain will regardless of what is written on their skin. Willa Wasserman’s figures, still lifes or landscapes exploit an ancient technique typical of the Renaissance tradition: the silverpoint, or more generally the metalpoint. For a long time the same technique was used for portraits of the powerful and official images. Willa Wasserman uses it to make quasi-confidential and domestic pictures.

[Read more on metailpoint technique in the Renaissance here. Ed.]

The artist’s use of brass and copper wools contribute to the gray and green palette of many of their paintings. The metalpoint marks are slightly reflecting, creating a patina over time. The resistance to erasure typical of this technique helps fix the indecision, fog and nuance of the subjects. Bodies and their visualization in a specifically technical realm are treated cautiously. A certain obsession seems to be layered in them, in their aura as things, in the way we perceive them and how we decide to represent them.

Concepts such as authenticity and autonomy should already sound obsolete. The same goes for the linear chronology that seems to structure the history of art. Anachronism, repetition, interruption, novelty and rupture are things to be reworked, to be used with a diversified approach. Considering their own imagination, Willa Wasserman’s perception and their possibilities of representation on canvas exist beyond the alternative between adhesion and betrayal.

According to a romantic conception of authorship and heroism, and according to a method of cynical and selected construction, the appearance of things is based on the cancellation of others. The paintings of the American artist navigate this contradiction, transforming the usual iconographies into the immaterial and intangible, for example in Figure with birdbath [a bather] (2020) and Park and lake (2020).

These works, as well as the convex still lifes, give meaning and shape to what they represent. At the same time they emanate a suspended potential, which manifests itself with resonances of perceptual uncertainty. A historical tradition and a self-critical approach are called into question in the sensual ambiguity of the traits with which subjects and objects appear in their own color scheme.

Both of these aspects are deformed into a hybrid between drawing and painting, between abstraction and figuration. It seems that in the quintessential place of the visible, that is the picture, an attempt at invisibility takes place. It is a process of carving out numerous and potential presences: historical entities that break out in a distorted and complex way.

As Willa Wasserman ironically states: “Unfortunately, the past did not (and does not!) need to be revived, it’s painfully present!” This is the case of painting and its haunted aura, its transitory definition. Referring to the legacy of European painting, the artist continues: “It is less as a grab-bag of references or productive launching points, and more like ghosts that appear by resonances, that continually refresh themselves through allusion.”

Critical inheritance is also a sign of a dominant discourse. Consequently, collaborative work bordering on anonymity becomes a strategy for the artist.In their individual pictorial practice, the artist makes visible losses, absences and erasures, which fluidly and placidly intertwine in the refusal of a vision, in a personal expression of imagination and perception.

Willa Wasserman’s floral compositions are the distortion of a tradition. Their painted bodies are so nuanced that they are devoid of any identity and gender. The quest for painting demonstrates the danger of a medium, its official and dominant character. The artist’s work elaborates this linguistic and significant terror, dismembering it from the inside thanks to the use of traditional techniques and subjects. Their perception is characterized by unresolvedness. The artist adds: “In terms of images, erased things come back, always.” Writes Jacques Derrida about the apparition of the inapparent: “This radical untimeliness or this anachrony on the basis of which we are trying here to think the ghost“. Is painting a radical anachronism?

Bibliography

Jacques Derrida, Spectres of Marx, translated from french by Peggy Kamuf, Routdledge, London/New York, 1994.

Brandon Labelle (eds), The Invisible Seminar, Bergen: University of Bergen, Faculty of Fine Art, Music and Design, 2017.

November 20, 2020