On the creative mentality of Patrick Weldé

By turning the countryside into a creative frontier Patrick Weldé finds a powerful antidote to urban clichés and fashion disillusionment

Let’s not misunderstand the art of Patrick Weldé (born 1992, Mulhouse, France). To merely see it as photography, hung on the wall of a gallery like any other work, would be a sin similar to considering De Stijl a mere artistic movement, Bruno Munari an abstract painter, or Nan Goldin a photographer. Patrick Weldé is not an artist, so to speak. He is not a fashion photographer, not a stylist, not even a media personality. Rather, he synthesizes different roles, reducing them to that common denominator called “creative mentality.”

He recalls: “Some time ago an agent came to me and told me that I was very talented, but that if I wanted to make my way into the world of fashion I had to stop photographing relatives and friends. I didn’t listen to him.” It is precisely the microcosm of a village of 1500 souls, a stone’s throw from Mulhouse and the Swiss border, that has offered Weldé the opportunity to use images in order to say something compelling about our time. He continues: “I grew up with the dream of leaving the countryside. At the age of 20 I finally moved to Paris, but I later realized that the city wasn’t the place where the best ideas came to me. I have now moved back.”

A bare, stubbornly agricultural countryside, with its gray and ambitionless sky, is the perfect metaphor for what cities have become. Stuck at home, with no restaurants and bars, no museums, no social life, today’s cities are dull. If you cannot benefit from the extraordinary human variety of an urban environment, why would deprive yourself of open spaces, the greens and blues, even the economic advantages of the country? As we learned a few years ago in Venice at the Architecture Biennale, the move from the countryside to cities has never reversed in history. We bet a pandemic will not change the rule, and neither will a pandemic turn art into a business for the periphery instead of the centre. Nevertheless, it is also true that the province is a surely less exploited scenario by creatives of all denominations, if only for a matter of logistics. Here is where Weldé’s intuition hits the mark. However surreal, out of place, and scenographic his characters may seem, the background to which they stick like glue is essentially real, unadorned, anonymous, immobile, raw, mute, absolute even. It becomes a scene within a scene, doubling the expressive force of the subject. The Alsace countryside ends up looking a lot like John Waters’ Baltimore, including its characters.

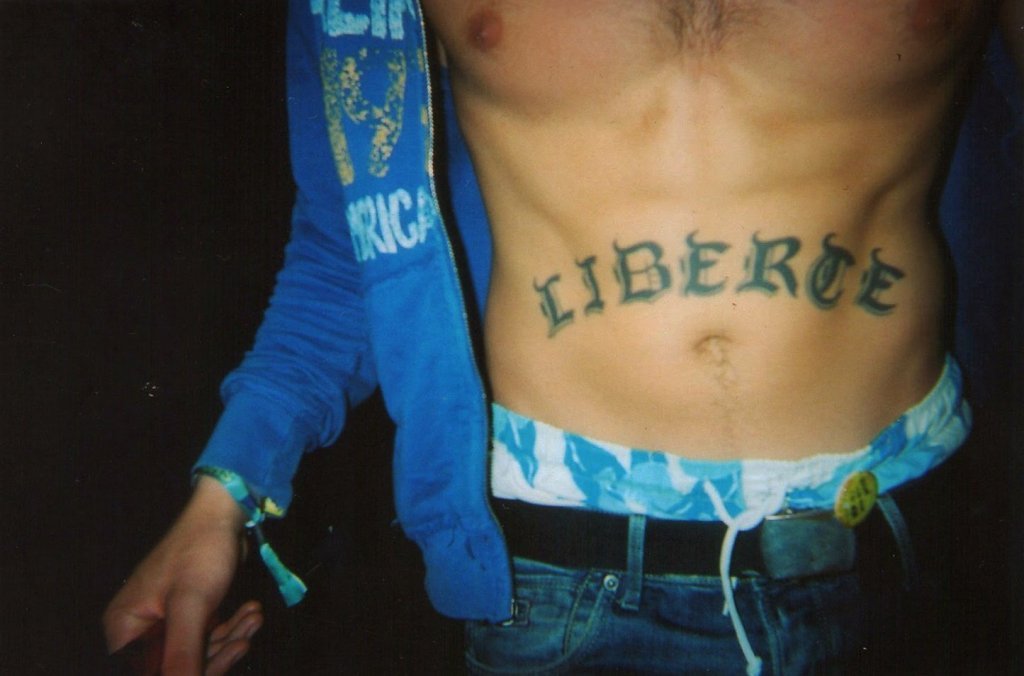

The second pillar that supports the aesthetic building erected by Weldé is considerably thinner than the first, but just as effective. From a photographic point of view, Weldé places himself, more or less consciously, along the line that starts from the pioneer of the so-called “queer photography” Walter Pfeiffer [here is to our interview with the artist. Ed.], going through Nan Goldin and Wolfgang Tillmans, reaching Ryan McGinley. With respect to these four cardinal points, the element that determines the uniqueness of Weldé’s language is an anti-lyrical tone of his images, a detached attitude at times. One of the aspects of his practice revealed by the solo show at Goswell Road (Fuck the System, 2016) is his ability to be expressive without resorting to lyricism, drama, or cheesy sentimentality. Freiheit, a limited edition photographic diary collecting some of the images published in an old blog, confirms these special features of his works.

The photographer is always an integral part of the scene he paints, sometimes hiding the camera or smartphone from his subjects. Weldé’s gaze remains inaccessible, even when the subject is himself. The image becomes neutral, timeless, free (freiheit) from mere autobiographical work that would otherwise be too self-referential. It matters little, therefore, to know whether one of the recurring characters suffered from a serious disease, or whether he was miraculously cured in the end. It matters little to know that Weldé’s blog attracted the caustic judgment of the locals conservative fringes – let’s not forget that the countryside is also one of the places in the West with a public to be scandalized. The author’s inaccessibility frees the image from the overweightness of a specific narrative, which is also why the images well connect to the semiotic universe of fashion, an universe that’s inspired Weldé for some time.

At the beginning we talked about artistic mentality. Given the two pillars mentioned above (the authenticity of the rural context and the inaccessibility of the author), the element that deserves to be included is the spirit with which Weldé photographs, that is, not to document a certain personality or an extraordinary fact in itself. His characters are by no means cursed, dreamlike, extreme, or in any way sensual. On the contrary, their authenticity makes them become a parody of certain clichés, a parody that we can also imagine in those characters drinking in a small village bar, sipping sweet liquors with uncritical self-confidence. Perhaps Patrick Weldé’s song is really the one of disillusionment.

November 9, 2022