Giangiacomo Rossetti: painting as a form of hospitality

We interpreted the paintings of Giangiacomo Rossetti with the help of their author and a fundamental exhibition in New York

When it comes to young artists like Giangiacomo Rossetti (born Milan, 1989), the comfortable art writing technique of interviews leaves us wondering. There is a clear responsibility in putting forward an interpretation of an emerging practice in the form of an essay. Even if a young artwork and author can speak for themselves, a specific reading by an external viewer is more than mere decoration. Perhaps this act of interpretation is even a necessary condition for properly showing or collecting any work of art.

After seeing the exhibition of Giangiacomo Rossetti at Greene Naftali in New York, we wanted to make an exception. We didn’t want to write an essay about his work, but interview him. There are artists, generally painters, whose art appears so closely linked to their personal story that their voice becomes crucial. What would Vincent Van Gogh be without his letters, or Giorgio De Chirico without his little treaty on painting technique, or Pierre Klossowski without his The Baphomet or his trilogy of novels dedicated to his wife Roberte? Sometimes, artists’ words are the necessary signs to navigate the path of their artistic journey. Sometimes, this is the case for young artists too.

Quite happy to contravene our own rule, we reached out to Giangiacomo Rossetti. The overwhelming yet unpacked intimacy in his new paintings was for us the justification for this unusual request. Unsurprisingly, the artist declined. He shared our idea about the necessity of an external interpretation in the form of an essay. Moreover, he wanted to step aside from any personal declamation. He nonetheless consented to a virtual meeting in order to clarify some doubts, answering our questions borne out of that untameable curiosity about his work that’s been bugging us ever since we first met him at the Milanese artist-run space Gasconade in 2011.

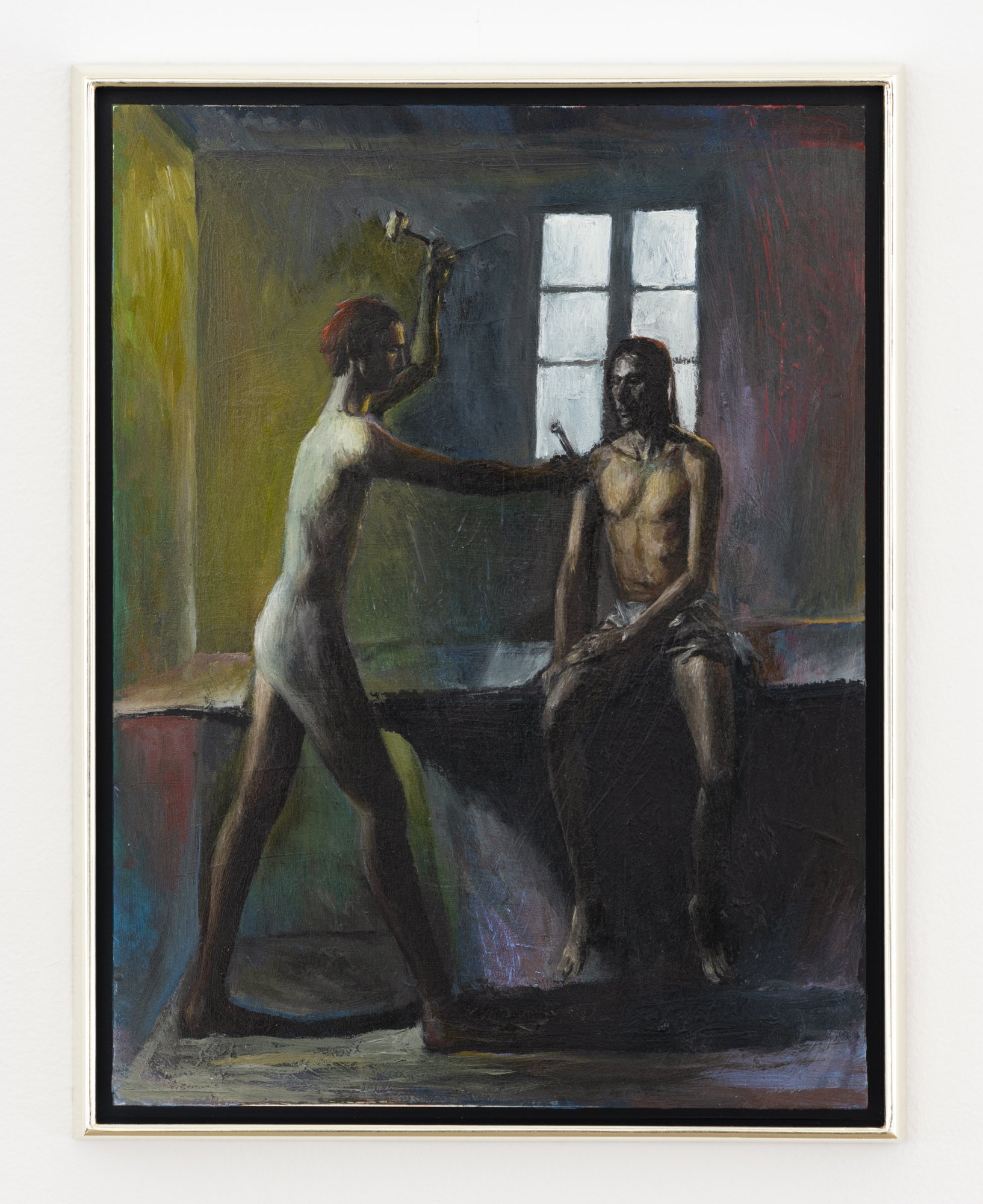

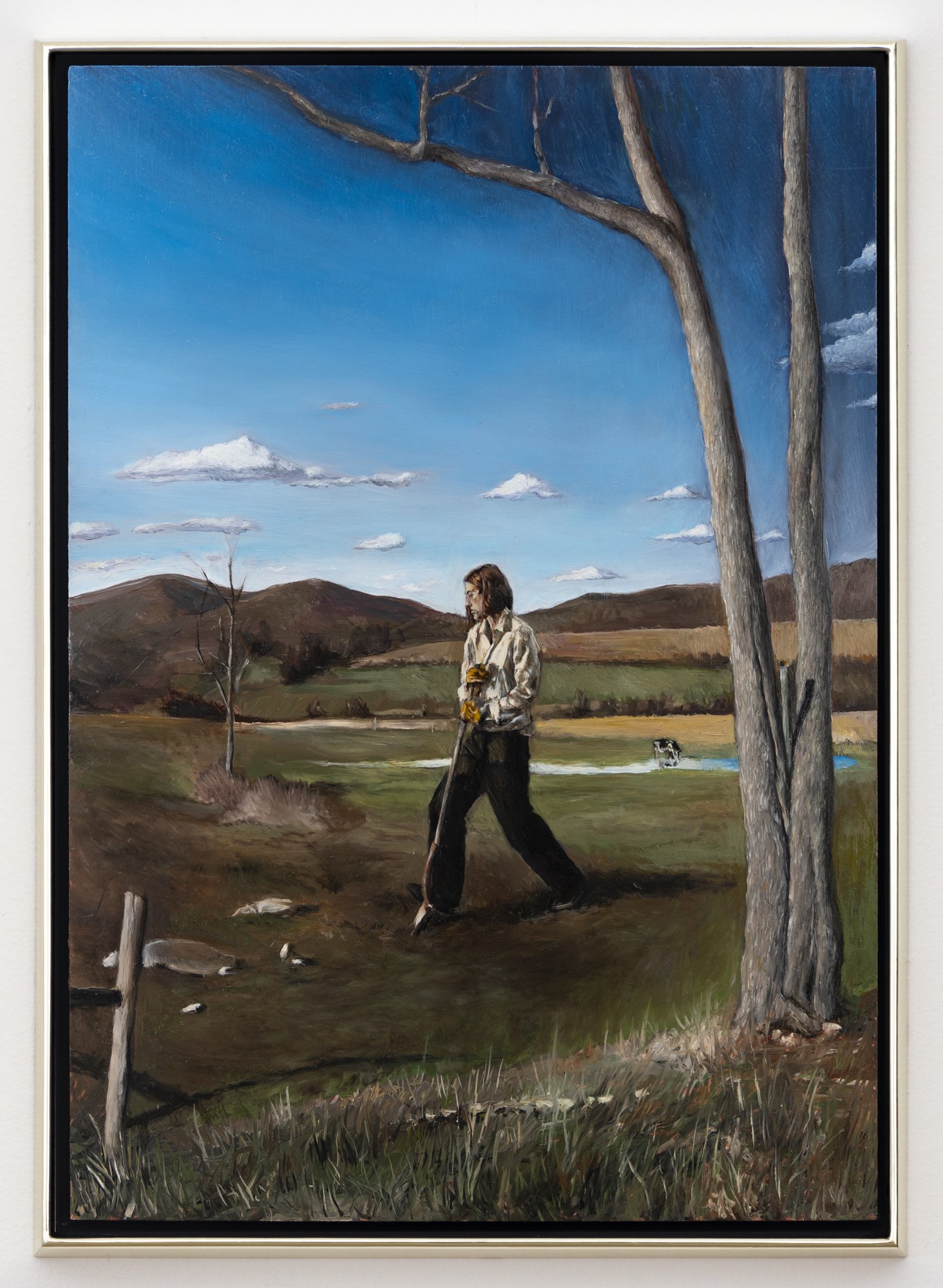

Our video call with Giangiacomo Rossetti lasted much longer than expected, unfortunately reinforcing our conviction that an interview would finally serve his case best. During our chat, he added a generous dose of those interpretative elements that only he could offer. He told us, for example, that Fantasia n.6 – Contratto devozionale owes its mystery to the fact that it was born, as a subject, directly on the surface and after many retouches over a semester – the two human figures actually used to be two planets. He told us that Fantasia n. 3 – La sepoltura was painted in New England, where the artist and his wife took refuge during the pandemic after living in New York for two years. The character in the painting is Rossetti himself, originally self-portrayed as someone who works the land, then taken elsewhere as Millet did in The Angelus. Rossetti also told us about Fantasia n.9 – La casa dagli spiriti buoni, revealing that the two protagonists are the artist Rochelle Goldberg and her husband Weit Laurent Kurz, painted in a forgotten 17th century Georgian house in a neighbouring village. The art passionate cannot but picture some contemporary Arnolfinis by Jan van Eyck here.

After our call we resigned ourselves to writing our analysis of Giangiacomo Rossetti’s work when we received an email with a precious new document. Here is the sought voice, without which we probably would not understand the sentimental bond that unites the artist with his characters. Neither would we understand how much the artist tries to make them feel at ease in the painting. The mysterious tension in the scenes originates from this formal challenge, and not from obscure, unspeakable, or surreal facts as one might think. As for Balthasar Klossowski (Balthus), and unlike his brother Pierre Klossowski, Giangiacomo Rossetti thinks about painting and his personal confrontation with it, technically and humanly. Rossetti appeals to his own impulsive and impatient nature to measure the relationship between himself and the medium. Both have their reasons. We also learn that his painting is never a practice that repeats itself in any of its phases. On the contrary, the path that leads to the final form is renewed each time, starting from different premises, overcoming errors and erasures. It is therefore unrepeatable. It arrives at an image that is not only true, but true in itself. It is said that the eyes are mirrors of the soul. For some artists, their voice reflects as much as their eyes.

January 31, 2022