Bringing light and liberation: Dalila Dalléas Bouzar

Dalila Dalléas Bouzar questions colonialism and patriarchy, trying to turn art into an instrument of liberation

“My goal has been to bring light to the center of my artistic practice and a spiritual dimension. I would like to share this light with others.” This is how the Algerian-born, France-based artist Dalila Dalléas Bouzar (born 1974) describes her practice. Trained at Beaux-Arts de Paris, she took up the challenge of figurative painting, which was not the mainstream at that time. Since then painting has become the arena for her ongoing research into femininity and patterns of dominations.

Identity

Identity is simultaneously a universal and intimate topic. Many artists and non-artists are exploring identity as a way to express their personal history and perspectives. In the case of Dalila Dalléas Bouzar, her work circles around an identity marked by memory and violence, which somewhat subvert it. Being Algerian and having grown up in France, she says of herself: “I am more than others confronted with this question of identity. I recognize myself in the idea of Homi Bhabha, who speaks of ‘the identity of the interstice and the third space’.” She also remarks: “In my biography, there is a degree of discontinuity in the Algerian culture I gained. Certain things were not conveyed to me by my parents, whether it’s memory or tradition.” [1] Thus, the artist uses this void to activate memory and knowledge, which she nourishes with her own current reflections.

This is also why self-portrait has become a central subject in Dalila’s practice— she is interested in the flesh of the body and questions of liberation through memory, for instance in her performance Ritual of displacement of bodies and Innerpast and her series of drawings Algeria Year 0. For Dalila Dalléas Bouzar, the body is closely linked to identity as she paints self-portraits and other portraits on skin-coloured canvas, spending much effort in making the paint as similar to the subjects’ skins as possible. In her philosophy, “the notion of the body as a vehicle also makes me think of the body as a surface of memory, which consequently carries and transmits memory.” [2]

From colonial powers to patriarchy

Dalila Dalléas Bouzar’s work on the links between colonialism and patriarchy also stems from a reflection on identity. She believes that the denied identity of colonised people, from whom everything was being taken, was unquestionably part of the ideological weapons of the domination. On the consequence of colonialism on Algerian identity, she says: “As a result of the acculturation driven by colonial rule, there’s a real lack of culture in Algeria and with respect to cultural memory, it’s a glaring problem.”[3] The artist claims that patriarchy is a system based on domination and materialism (ownership and the importance of the object), while colonialism is the exacerbated product of the patriarchal system. It creates a context where responsibility is denied, where freedom is withdrawn in order to keep the human in a form of childishness.

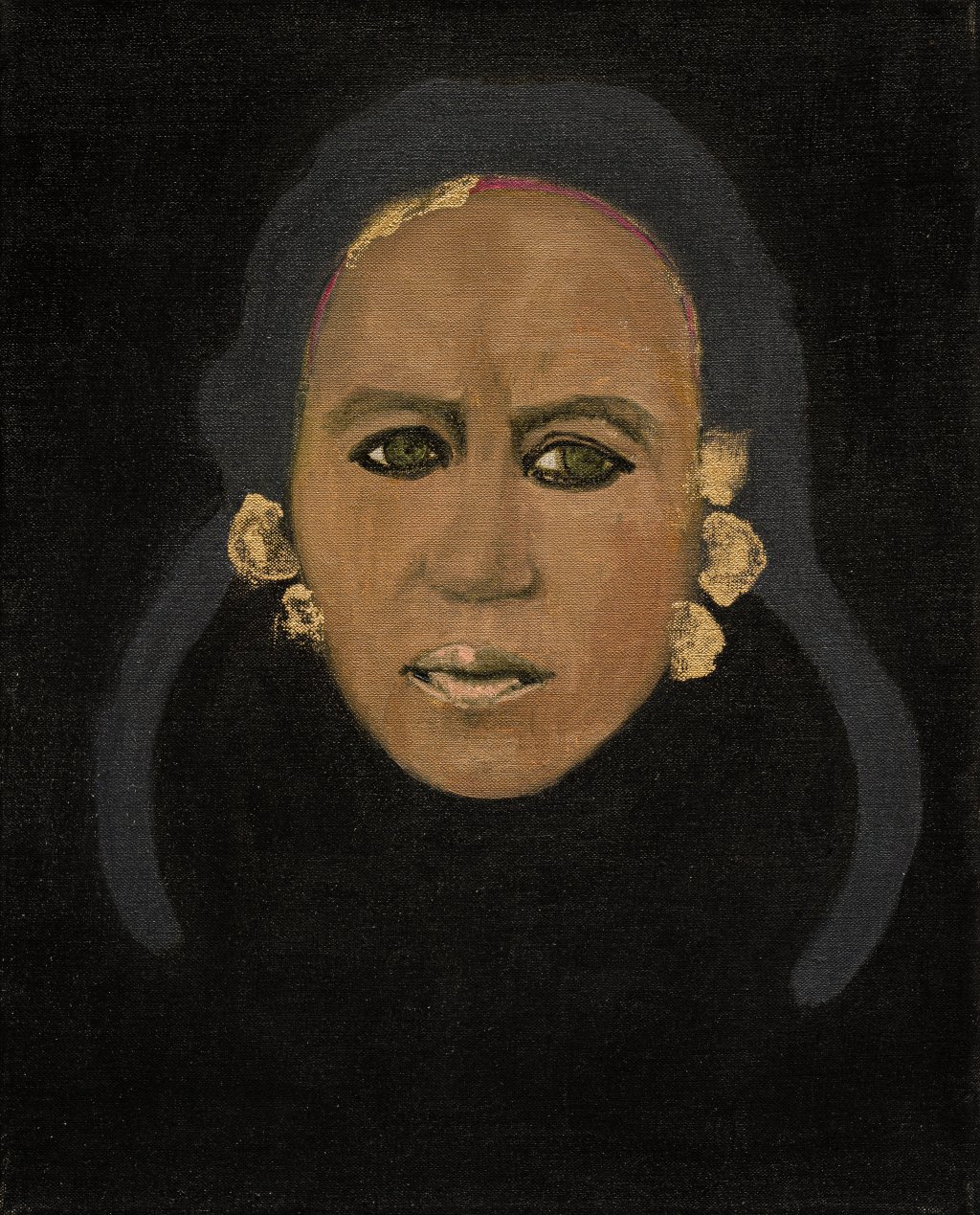

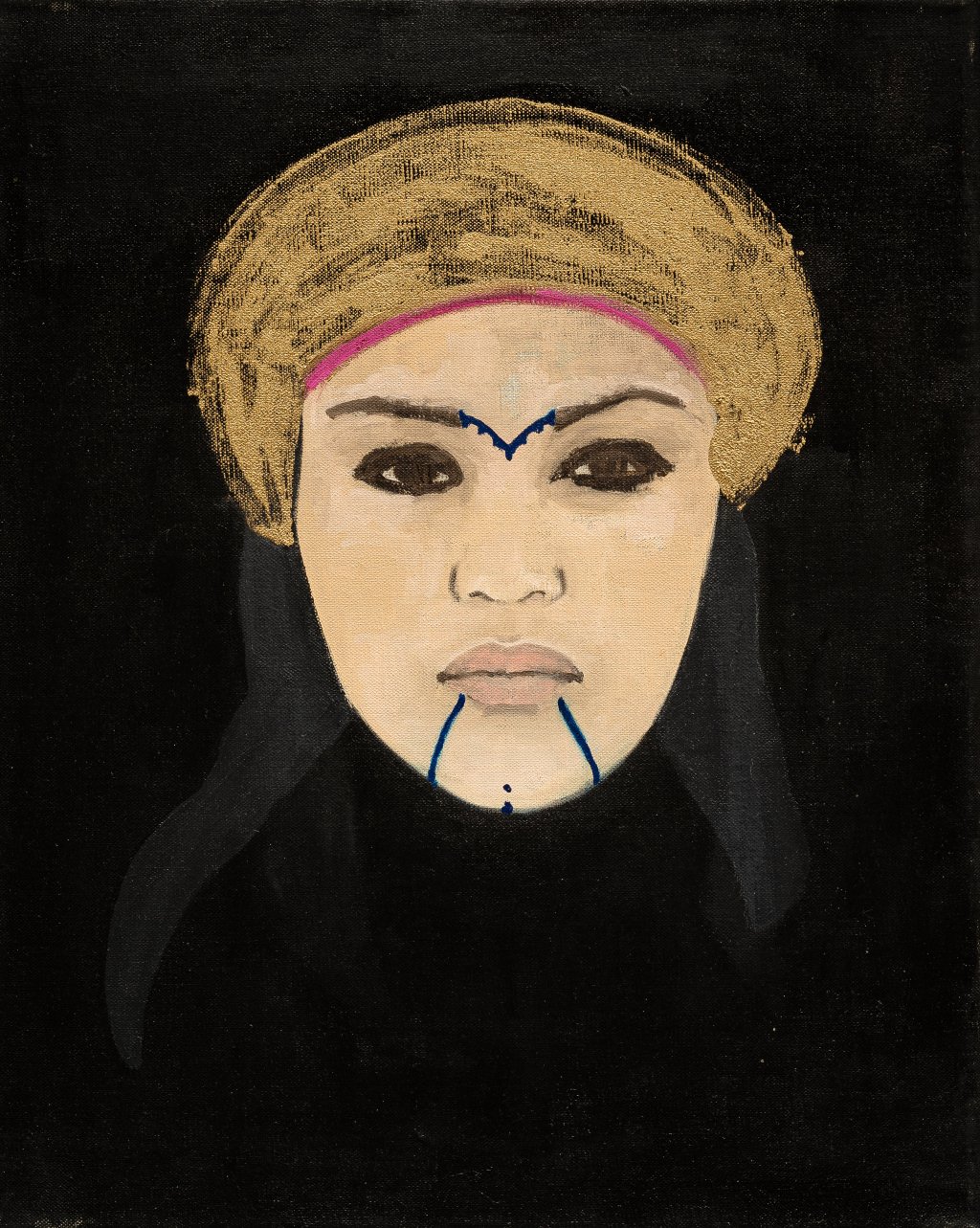

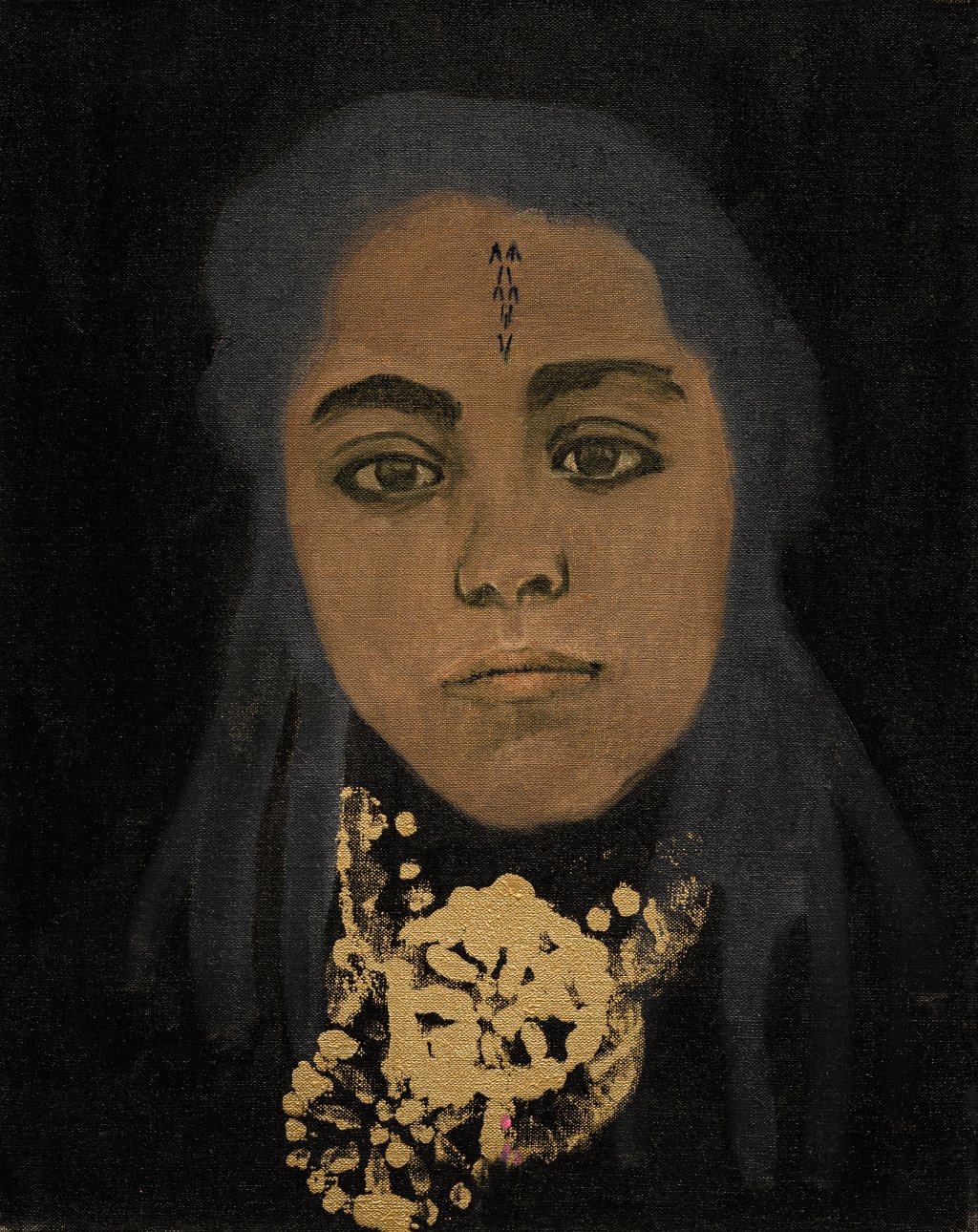

This link between colonialism and patriarchy is visible in her series of portraits titled Princesses, in which each of 12 Algerian women are painted on a black background gazing back at the viewer. The images are based on Marc Garanger’s photographic campaign during the Algerian War. Dalila explains that “Delacroix’s Femmes d’Alger, like Marc Garanger’s photographs at the origin of my series Princesses, both raise the question of the double submission to the coloniser and to patriarchy.” [4] The Princesses portraits seem to subvert the male gaze in classical Western painting, which is directly a representation of the patriarchal oppression. According to Dalila Dalléas Bouzar, men’s relationship with the world is fragile and inseparable from that with women: “The system of male domination modifies this relationship, by assigning women the position of subject vitally dependant on men, even going so far as to brainwash women so that they only see themselves through the prism of the male gaze.” [5] The subversion of the male gaze in Princesses is a way to revolt against both colonial and patriarchal violence at once.

Dalila Dalléas Bouzar, from the Princesses series, 2016, oil on linen canvas, 60×50 cm. Ph: Photo Gregory Copitet. Courtesy of Dalila Dalléas Bouzar – Cécile Fakhooury gallery.

Dalila Dalléas Bouzar, from the Princesses series, 2016, oil on linen canvas, 60×50 cm. Ph: Photo Gregory Copitet. Courtesy of Dalila Dalléas Bouzar – Cécile Fakhooury gallery.

Dalila Dalléas Bouzar, from the Princesses series, 2016, oil on linen canvas, 60×50 cm. Ph: Photo Gregory Copitet. Courtesy of Dalila Dalléas Bouzar – Cécile Fakhooury gallery.

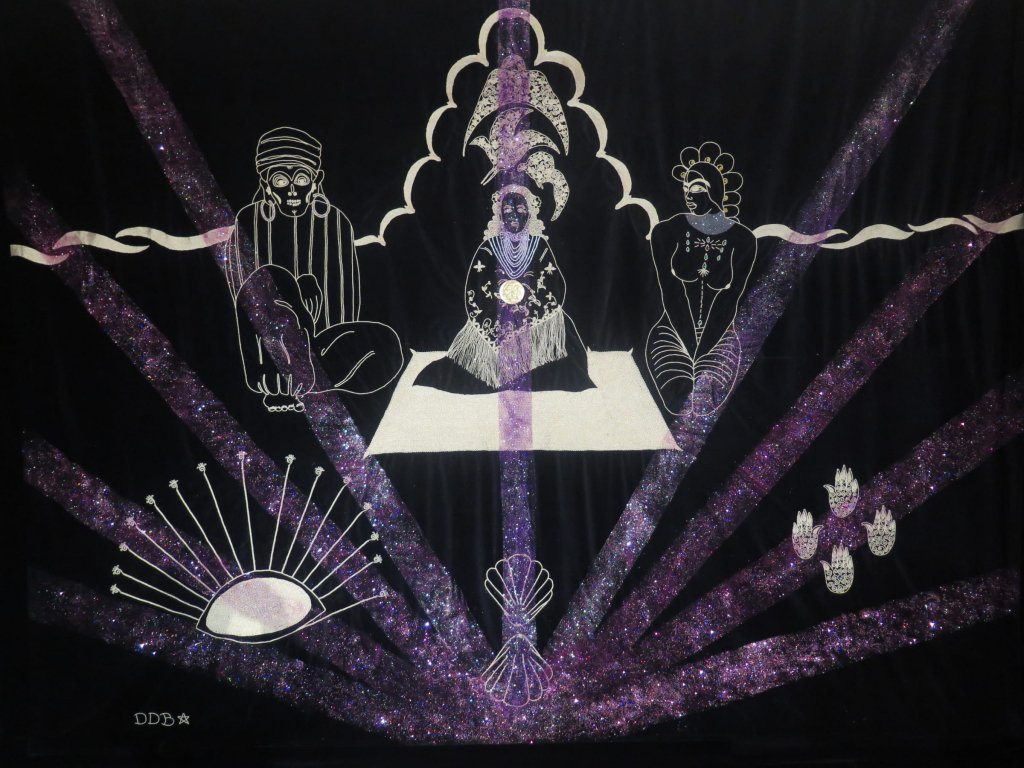

Dalila Dalléas Bouzar, from the Princesses series, 2016, oil on linen canvas, 60×50 cm. Ph: Photo Gregory Copitet. Courtesy of Dalila Dalléas Bouzar – Cécile Fakhoury gallery.

Dalila Dalléas Bouzar does not approach this topic from a distant third person’s perspective. Instead, ever since her childhood, she has investigated attentively the violent treatment of the female body, from the little girl to the old woman. She sounds outraged by the violence against women when she declares: “I always knew that it was completely wrong and that it needed to change.” According to the artist, the female body is a major issue in patriarchal society— it is access to reproduction for the species but also for capitalist society; it is the subject-object archetype, which defines the system of submission and domination. She came to the core of her artistic practice with the belief that “to question the status of women is to undermine the entire system of domination. To change the societal paradigm, we must free the female body.” This declaration sets the backdrop for her monumental embroidery work Adama (2019), a tapestry embroidered with gold thread on black velvet, 4 metres wide and 3 metres long, with three life-size figures of the three ages of women (child, adult, and elderly). It uses the same technique as the karakou, a traditional garment worn by Algerian women at weddings. Dalila interprets it as a traditional symbol of the submission of women, highlighting these issues and shedding some light on the representations of the female body in rituals and ceremonies as components of patriarchal domination. Adama is a piece closely linked with women’s position and visibility within society as well as their relationship with men within the patriarchy.

Liberation

In face of oppression, Dalila Dalléas Bouzar seeks liberation in her work. She says: “When I talk about liberation, I am talking about freeing oneself from the constraints placed on bodies and minds. Of course, the heritage I have from the history of Algeria prompts me to reflect on what colonization was and how it exerted an unbearable oppression on the body.”

Dalila’s approach to the recurring question of how to liberate ourselves from patriarchy hinges on solidarity and creativity as a space for expression within family and society. Her work Adama is an example of her collaborative attitude: she traveled to Algeria to produce the work with local embroiderers, who constantly have to find space for creative craftsmanship in their patriarchal households. The artist sought to divert this technique from its traditional function to stimulate further discourse on women, their bodies and social condition, turning it into a new kind of power tool for the purpose of liberation.

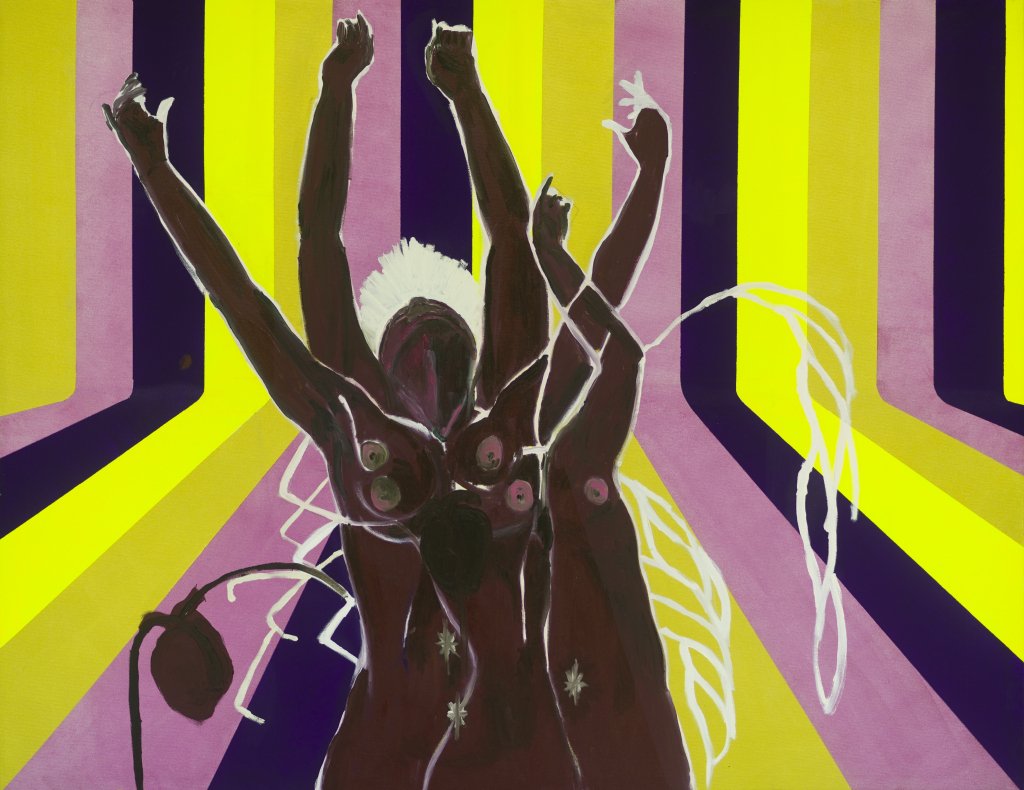

Her painting series Sorcières brings liberation through the history of the witch. Witches were hunted in Europe because they possessed powerful age-old knowledge, a precondition for their intellectual and financial independence, and which, therefore, threatened the patriarchy at the time. In Sorcières the artist wants to show “bodies that are free, free from all restraints, and that give access to freedom.” [6]

Dalila’s performance is a ritual of body displacement on a symbolic level. Through eating a symbolic body made of marzipan and dressing in a wedding gown, she tries to make her body a new place, a place of emancipation. At the end of the ritual, the artist paints her face with gold, which is the symbol of power and light, and puts on her mother’s golden crown, inherited from her grandmother. This act of reviving her descent allows her to engender a potentially restorative process of ‘trans-generational’ liberation.

On the whole, Dalila Dalléas Bouzar is hopeful about the future of social systems. She is convinced that even if female domination over men will not exist, the end of patriarchy “will surely be exciting and liberating for everyone.” Perhaps with similar spirit, she thinks the future of painting is bright too, as painting is but a crucial part of humanity: the expression of a deeply ingrained need for representation, imagination, and connection to reality.

Note: Dalila Dalléas Bouzar is having a solo show at Cécile Fakhoury gallery in Paris (Eden, until 26th March 2021).

[1] Innocente, catalogue of Dalila Dalléas Bouzar, Galerie Cécile Fakhoury, 2019-2020, p.37

[2] Ibid., p.36

[3] Ibid., p.38

[4] Ibid., p.42

[5] Ibid., p.87

[6] Ibid., p.47

February 24, 2021