The annoying fly and symbolic paintings

Flies buzz around a few Renaissance, Netherlandish and Baroque paintings, full of jokes, meanings, and hellish symbolism

What a sense of ostentatious beauty butterflies evoke. And so do crickets and cicadas, true bearers of unassailable literary dignity, along with the industrious ants and the sedulous bees, and all the other insects that enjoy the favor of the arts. Then it comes to flies… those creatures that squeeze any possible murderous inclination out of us. Despite our threatening, disheveled slaps, flies do not easily desist, landing near us or our food whenever they can, indifferent to death and disgust, irritating they exist.

With little disconcert, one surprisingly comes across these annoying insects in many paintings from the Renaissance and the Baroque era, from Petrus Christus to Carlo Crivelli and Vincenzo Campi, from Cima da Conegliano and Guido Reni to Guercino, and then Jacopo da Bassano, Louise Moillon, Balthasar van Ast, and Giovanna Garzoni. The irksome buzz and scuff of the black insect has marked art history.

“I would not like to suggest the image of a murdered fly,” writes Giorgio Manganelli in his Musca Depicta (painted fly). “This little animal seems entrusted with important sacredness and symbols too.” he continues. Flies were indeed artists’ dears until the 17th century, beginning with the anecdote of Giotto and the fly. Writes Vasari: “It is said that young Giotto painted such a realistic fly on the nose of a figure by the older Cimabue, that when the master resumed his work on this figure, more than once did he hunt for the insect before realizing his mistake.” The feats of the trompe l’oeil had already been recounted by Pliny in his famous bunches of grapes painted by Zeusi that deceived the birds. Imitative prowess was surely part of the folklore in the Renaissance workshops, but why the fly?

Let’s have a look at Guido Reni’s Country Dance. The scene depicts an anomalous subject for the painter: a natural landscape with a party in the moonlight, a dance organized by a group of peasants but attended by noble ladies and gentlemen too. The characters are seated in a circle next to some trees and a river flowing as a hymn to the locus amoenus. In the center, a young peasant invites a lady to open the dance. All this moment seems so idyllic, so perfect, until the viewer is distracted by two large flies buzzing on the top right corner of the picture, scurrying on the blue sky of the otherwise enchanted night. Don’t we just want to chase them away, these fat and three-dimensionally out of scale insects. When our gaze lands on these flies, the painting is no longer the same.

Considering the story of Country Dance, these flies seem to have long distracted the gaze of the connoisseurs too. Lost for a long time, the work was eventually purchased in 2020 by the Galleria Borghese in Rome, but still in 2008 it appeared on the London antique market, attributed to an anonymous Bolognese artist. The hand of Guido Reni was finally recognized also thanks to the identification of the painting in the inventories and descriptions of the Scipione Borghese collection. After the exhibition at TEFAF in March 2020, Guido Reni’s Country Dance returned to Italy in the collection of its former owner. Reni’s trompe l’oeil is the surprising mark of the virtuoso: the baroque illusionistic game is mischievous and perfect, but an overdone nuisance too, and even a hidden message perhaps: flies titillate disorder with their paws, insinuate their filth, warning us not to plunge into the nocturnal magic of dance.

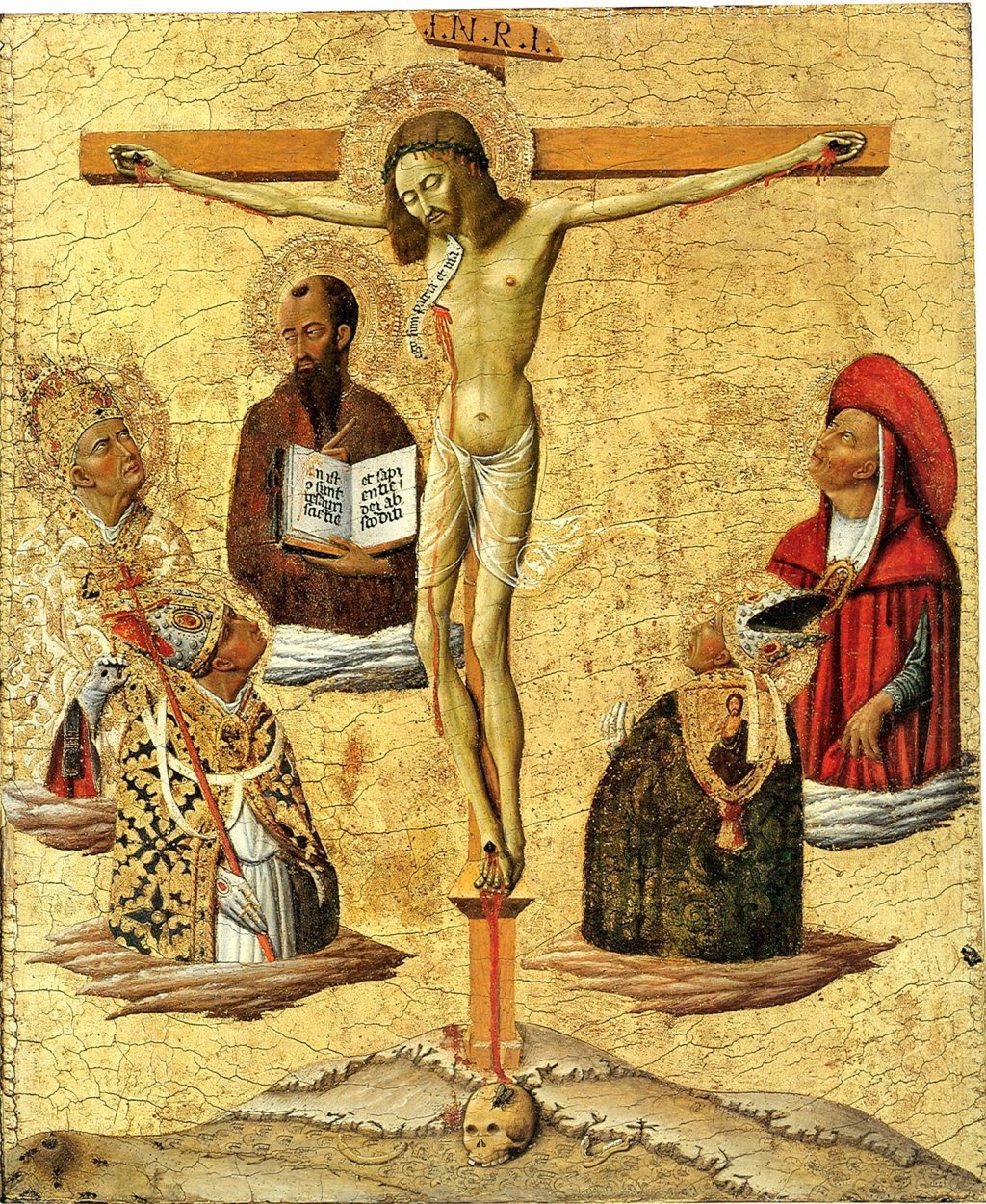

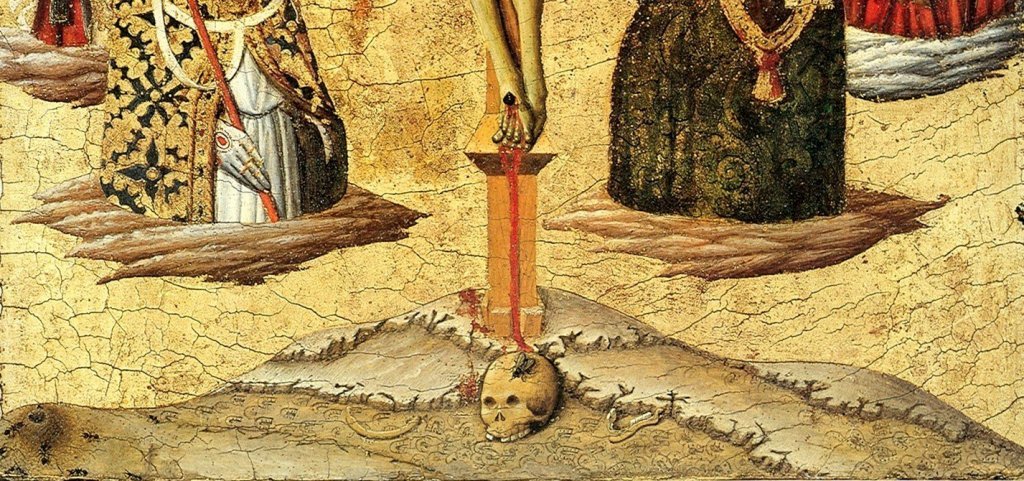

More commonly, the musca depicta (painted fly) is found in Vanitas religious paintings, resting on the skulls kissed by the penitent Magdalene, on the meditation skulls of Saint Jerome or those at the foot of the Christian cross. In the Mystical Crucifixion attributed to Matteo di Giovanni and dated 1450 now at the Art Museum in Princeton, four theologians navigate like clouds on a gold background in contemplation of Golgotha. Next to the cross is the fateful skull with fly, belonging to Adam and showing the trickle of blood that gushes from Christ to redeem humanity from the original sin. Above it is a huge fly of exaggerated proportions. Joos van Cleve even painted a fly going into the naked skull in St. Jerome in his Study from 1550, now housed at the Salzburg Museum. These are deadly flies, large black spots acting as a goad for the devotees to go beyond the pleasures of earthly flesh and corruption. Thus, despite their infernal livera, the flies are transformed into symbolic moralizers.

The omnipresence of death in time and space also makes its way into the mythical Arcadia, the Greek region of poetic immortality. Et in Arcadia Ego is the title of a 1622 work by Guercino preserved in Palazzo Barberini. In it, two shepherds laboriously emerge from a barrier of trees in this mythological place inspired by the Eclogues of Virgil, a symbol of the golden age. But even here the reign of Death prevails. Above an altar there is an old mossy skull, a funereal emblem, and for this reason also Arcadia becomes a favorite land for flies, worms and mice.

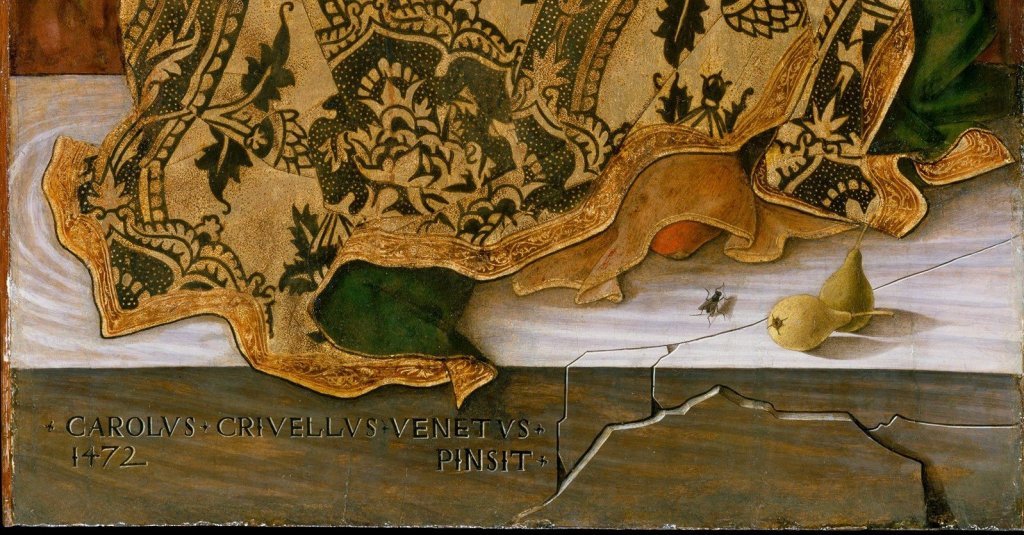

The paintings by Carlo Crivelli where Mary and the Child in the company of black insects could be seen as sacred yet weird conversations with a fly. From Crivelli’s Madonna Lenti (1472-1473) to Madonna with Child Enthroned (1472), both held at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, to Madonna and Child (1480) at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the artist was obsessed by the presence of the insect to challenge the gaze of the holy protagonists.

Here the fly is not the illusory ploy outside the painting, the joke to make people believe that reality prevails, as Reni wanted to affirm in his Country Dance. In Crivelli’s works, the insect is in the picture instead, it is one of the protagonists. Everything is in dialogue with it, turning the animal into an intruder of naturalism into the world of metaphysics. The Madonna, born terrestrial and turned celestial, is the only one who can really understand a creature like the fly, perhaps anticipating the Judgment Day when she herself will intervene in favor of the Beelzebub insect, the god of flies, recognizing the creature as a fallen angel.

Plenty of insects populate the history of beautiful still life painting: garlands of flowers, baskets of fruit, game or fish are all accompanied by cute tiny animals, yet flies are still preferred for the depiction of Memento Mori. Diptera are the typical accessories of the Vanitas pictures, representing the living in what is destined to perish. The representation of the blue blow fly, a painterly challenge in itself, is instead virtuosity and mocking of the viewer at once.

The first presence of flies in still lifes is found in Dutch-Flemish paintings of the 15th and 16th centuries, perhaps imported from earlier Italian traditions. It could be argued that the anecdote of Giotto’s prank with the fly mentioned above created the narrative substratum for the trompe l’oeil of the Dutch-Flemish musca depicta, a trope that comes back to Italy in the 16th century and disappears completely by the end of the 17th century. From a popular motif, the annoying and symbolic insect eventually met the flypaper.

The first known Flemish painting with fly is the Portrait of a Carthusian by Petrus Christus from 1446, now at the MET in New York, a work that greatly intrigued Erwin Panofsky. This portrait is transversely linked to still life: the monk of the portrait is supposedly the Carthusian philosopher Dionysius van Rijkel, author of De Venustate Mundi, a text in which the beauty of the universe is classified in a hierarchy which includes, albeit at the lowest level, also the beauty of insects as a testimony of the harmony of creation.

Almost 200 years later, a small fly rests on a shiny grape in Still Life by Louise Moillon from 1630, now at The Art Institute of Chicago. Representatives of the ephemeral are a fly and a drop of water in Still Life with Flowers by Ambrosius Bosschaert from the collection of the Mauritshuis in The Hague. A large fly dominates a yellow apple in Balthasar van der Ast’s Basket of Fruit (1632), now at the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin. The insect is almost directing the dance of beetles and dragonflies buzzing beneath it.

When it comes to flies, we should also mention the still life pictures by Giovanna Garzoni, truly inspired by the Dutch pictorial perfection. For example, in her Canina con Biscotti e Tazza Cinese (1648) now at Galleria Palatina in Florence, two large flies run around on a biscuit reserved for the “virgin kennel” as Parini would call the puppy of the Grand Duchess of Tuscany Vittoria della Rovere. The dog is lying on a candy pink table and her bowl is a precious Chinese porcelain. Perhaps it is improper to define the two fat dipterans as a naturalistic intrusion in Garzoni’s painting, as they look much more like two lackeys who move with the music of the fly scene composed much later by Offenbach.

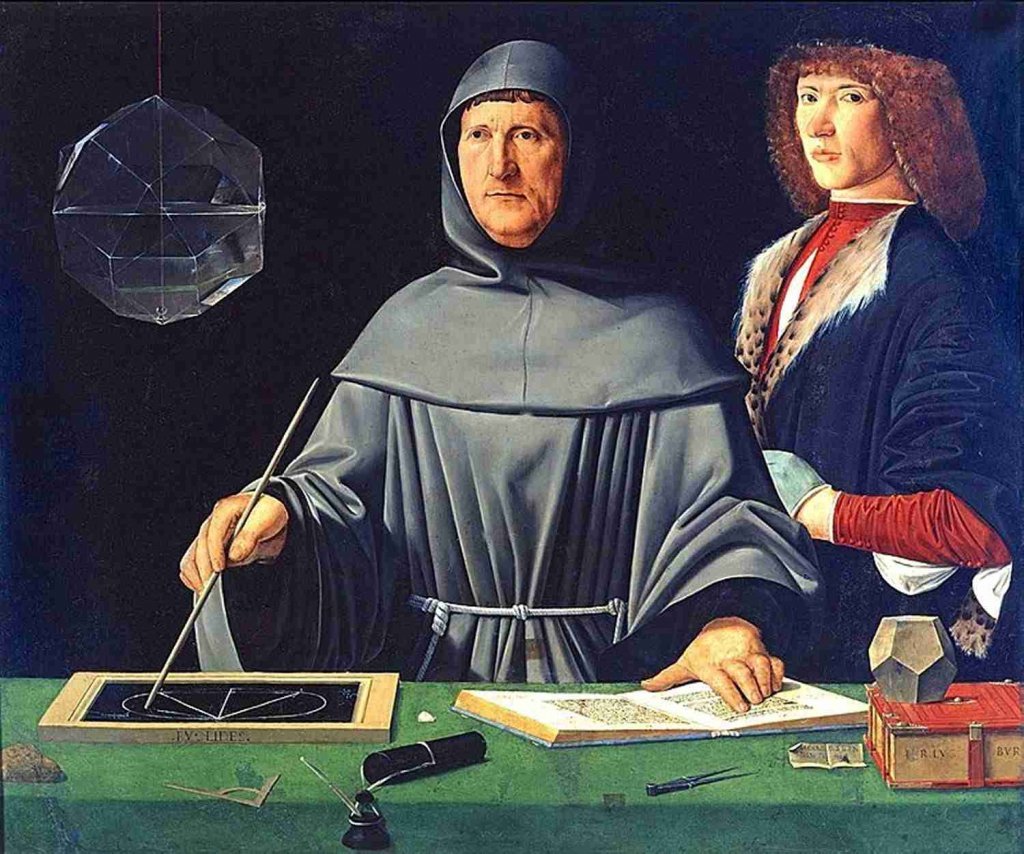

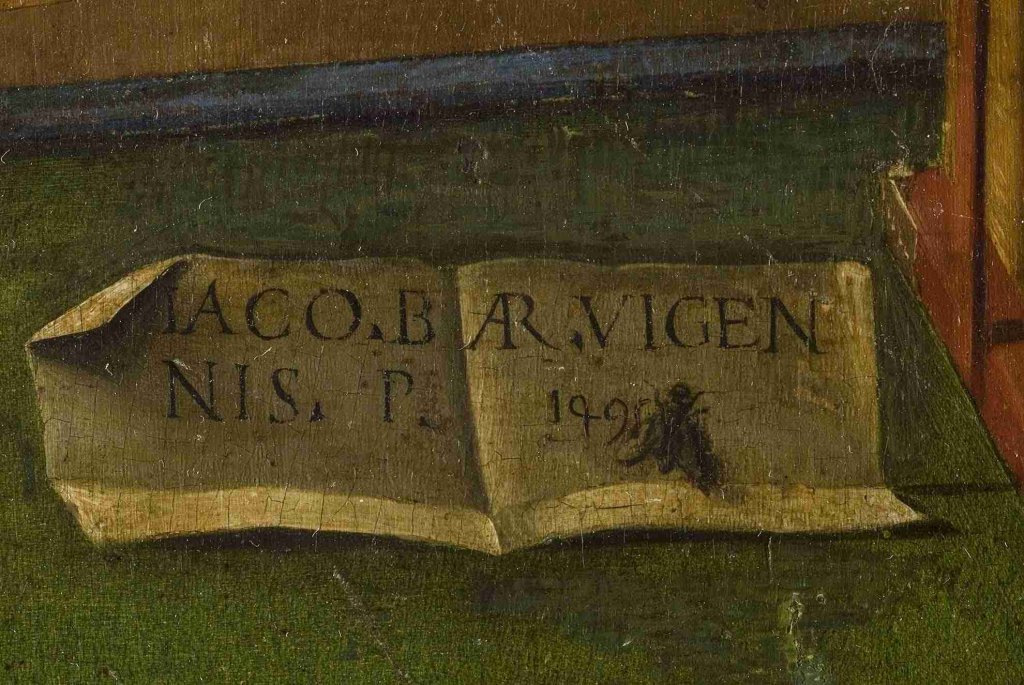

Here comes again the insect in the work of the artist who signed with his fly seal: Portrait of Fra Luca Pacioli (1495), a painting at the Capodimonte Museum in Naples, attributed to Jacopo de’ Barbari. The fly is in the black wax seal on the scroll at the bottom next to the artist’s autograph. As to other strange signatures, in the Annunciation by Cima da Conegliano, now at the Hermitage in St. Petersburg, a long fly stretches over the cartouche with the artist’s name.

This yoking between the painter and the insect is an act of humility, the admission by Cima that every human being is but a future meal for flies. Yet the insect is external to the painting, playing a Giotto-like stunt indeed, but also inflated with much more meaning: no longer the lowest terrestrial creature but a categorical Great Fly, a sort of “fly in itself” that mysteriously makes this picture truly contemporary.

Bibliography

- André Chastel, Musca depicta, Franco Maria Ricci – Milano, 1984

- Luciano Di Samosata, Encomio della mosca in Dialoghi e saggi, Bompiani, Milano, 1994

- Erwin Panofsky, Early Netherlandish Painting, Harper and Row, Icon Edition, London, 1971

- Erwin Panofsky, Studi di iconologia. I temi umanistici nell’arte del Rinascimento, Einaudi, Torino 2009

- Giuseppe Elio Barbati, La nascita della natura morta in Europa, Kairòs, Napoli, 2020

- Pietro Zampetti, Carlo Crivelli, Nardini editore, Firenze, 1986

March 12, 2021