Horace Pippin is a misunderstood realist

Labels such as “primitive,” “naive,” and “folk” can conceal prejudice and racism. Horace Pippin was a realist instead

Here is how I first came across Horace Pippin (1888-1946) about ten years ago, an anecdote that shows how chance and destiny can enrich knowledge more than mainstream studies. Horace Pippin is one of those great artists who didn’t produce much, whose retrospectives are organized only every twenty years or so and never in Europe anyway. The last took place in 2015 at the Brandywine River Museum of Art, Pennsylvania. The penultimate was traveling between various American museums in 1994 and 1995. Ten years ago, my passion for Pippin began after I looked up “artist, catalog, Pennsylvania” on Ebay: the catalog of one of these shows titled I Tell My Heart: The Art of Horace Pippin came up in the search results. [1]

[Here is another text on a freshly discovered 20th century artist, Luigi Zuccheri. Ed.]

Horace Pippin was born in an African American household in February 1888 in the northeastern United States, West Chester in Pennsylvania to be precise. Soon the Pippin’s moved to Goshen, NY and then to Middletown, NY where Horace’s mother worked as a maid. Aged 10, the artist won a box of crayons in a local competition with which he would draw religious subjects learned in the local African Methodist Episcopal Church regularly attended by him and his family. The young Pippin would attend racially segregated schools until the age of fifteen, after which he began working as a hotel porter first and in an iron smelting factory later.

He was finally sent to France during WWI, enlisted in the famous 369th infantry regiment known as the glorious Harlem Hellfighters or Black Rattlers, composed mainly of African Americans and Puerto Ricans. Pippin would fight in the trenches of the Argonne forest until a German sniper hit him in the right shoulder, compromising his mobility for the rest of his life. In order to paint, the artist needed to support his right arm with the help of his left one, continuing to hold the brush with his right hand. Upon his return to the States, he obtained the croix de guerre, which came with a disability allowance. He would nonetheless deliver the laundry washed by his wife to raise extra cash. Meanwhile, he began decorating boxes of cigars and finally made his first oil painting in 1928. It is titled The Ending of the War, Starting Home.

It is in 1937 that Horace Pippin’s rich and curious exhibition career began, which, when studied in detail, tells the story of a battle against racism fought little by little, in spite of everything and everyone. Like all artists, his first opportunities were local. An art centre in his hometown of West Chester first included him in a collective exhibition, which would turn into a solo afterwards. Already in the following year, four paintings by Pippin reached MoMA: an exhibition titled Masters of Popular Painting. We will come back to the actual meaning of the term “popular” later in the article.

The seminal Alfred H. Barr, Jr., the organizer of those historiographical exhibitions that would change the course of 20th century art history, was at the helm of MoMA in those years. However, it was a woman who took an interest in Pippin first: the curator Dorothy C. Miller, who had previously organized a series of collective exhibitions titled Americans at the museum since the 1940s, including artists from all the fifty states. Apparently she came across Pippin’s work through a notary friend in West Chester while asking for information on the “Negro primitive” or “naive artist.” We will also come back to these terms later in the article.

Thanks to a curious curator, a woman who was not satisfied with main cities or mainstream art, Pippin struck a prestigious debut. In the following years, the artist began working with a gallery in Philadelphia, as well with Cézanne dealer in New York Étienne Bignou. Most importantly, Pippin found himself under the radar of the prominent African American philosopher Alain Leroy Locke, the so-called “Father of the Harlem Renaissance” who included him in his book The Negro in Art: A Pictorial Record of the Negro Artist and of the Negro Theme in Art (1940). This inclusion comes with some issues as we will see.

Counting on various successful exhibitions, Pippin’s art was finally acquired by the Whitney Museum and featured in important magazines such Time, Life, and Vogue. The latter also commissioned works to Pippin, who died at the age of 58 in 1946, after a few last years of financial stability but personal unhappiness. His fleeting production stood among contemporaries such as Walker Evans and his most iconic period, Georgia O’Keeffe and her newborn love for New Mexico, Philip Guston and his Mexican-inspired murals, the great African American painter Jacob Lawrence and his Migration Series started at the age of 23, Florine Stettheimer at the end of her earthly existence.

For most of his life, Horace Pippin didn’t have a studio. He painted in one of the rooms in his house, sharing it with his wife and son. He would make art at night with the help of an electric lamp, delivering laundry during the day. He could not afford refined pigments or canvases. He would paint as much as his situation allowed him. Economic success came only towards the end, when he could finally devote himself to painting even during the day.

Formally, his small works display rather thick and protruding surfaces. Pippin reworked parts of the painting, but the thickness is mainly due to his peculiar technique: if he needed to paint a bed with sheets and blankets for example, he would not divide the overall figure into sections, but would paint the sheets first, then the pillow, and finally the blankets on it. This was a kind of “realist” way to approach figurative painting, which created the singular material thickness of his pictures.

Pippin worked on canvas at times, but also on wooden panels. He achieved considerable mastery in the pyrography technique, sometimes letting the pyrographic images live as spectra of pure unpainted drawing within realistically colored landscapes. His subjects included portraits, still life, war and biblical scenes, domesticity, history, rural and urban landscapes, and even allegories. Two works are emblematic within Pippin’s oeuvre: Mr. Prejudice for its iconographic references; Christmas Morning Breakfast for the peculiarities of the artist’s technique. I will deal with them in this order.

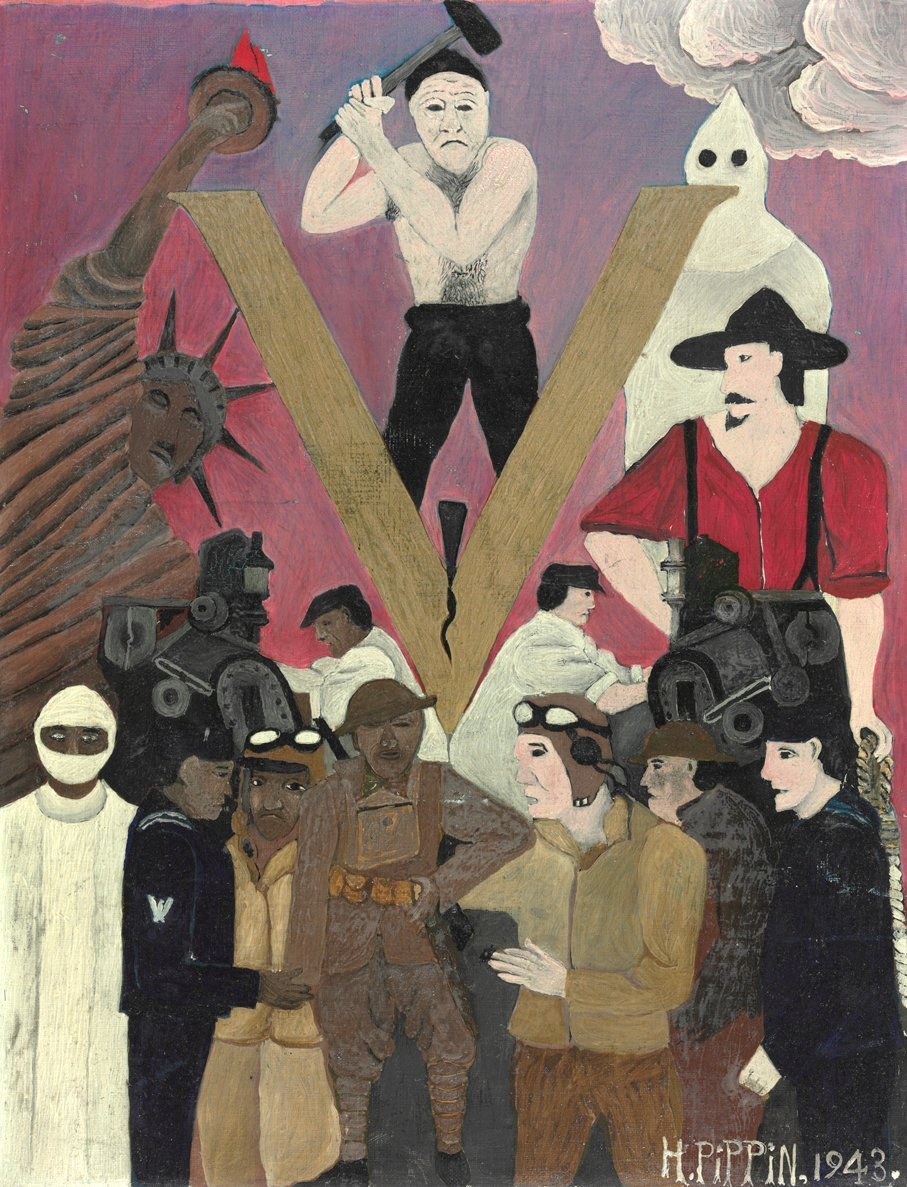

Mr. Prejudice (1943) is a small but rich painting. At the center of the composition is Mr. Prejudice, a white executioner who hits a nail on a wooden V, the V of victory and the famous symbol adopted by Winston Churchill. The lower end of the V divides two machinists, one is African American, the other is white. We are in the midst of WWII. Racial discrimination in the metallurgical industries is causing a slowdown in the production of resources for the war. On the right side, a cloud anticipates the menacing presence of a hooded Ku Klux Klansman and another chubby white man holding a noose, a reference to the lynchings of African Americans that Pippin may have witnessed. To the left of the composition, the Statue of Liberty is painted in dark brown. At the bottom are the segregated workers: white people on one side, African Americans on the other, including a self-portrait of Pippin wearing his WWI uniform.

The sky at sunset anticipates the color palette used by Guston in the following decades. On an iconographic level, the painting deals with the American army in both world wars. For many African American soldiers, fighting in WWI also meant hope for integration. They soon realized the opposite was happening however: the KKK was expanding precisely during those years (from 1918 to 1920). The surviving African American soldiers, traumatised by the horrors of war, returned home to find but a grim destiny.

Christmas Morning, Breakfast (1945) is one of Pippin’s many depictions of domestic scenes. A mother looks after her baby during a Christmas morning in a humble house that nevertheless does not lack gifts and decorations. The floor, the rugs, the division between wall and ceiling are not represented in perspective, unlike other paintings such as Saturday Morning, Breakfast (1943) or Saturday Night, Bath (1945), in which the rooms are reproduced realistically, completed with geometric plays of shadows worthy of the most cunning modernism. The lack of perspective in Christmas Morning, Breakfast is therefore a choice.

Pippin eliminated trompe l’oeil but didn’t skip realistic details, for example the portions of peeling plaster behind the bench or by the window, or the tiny brushstrokes with which he reproduced the softness of the rugs. Why does an artist avoid perspective when they know how to use it? Is it an aesthetic choice, a declaration of poetics, an instinct? Here are some words from Pippin: “Because I paint things exactly the way they are. … I don’t do what these white guys do. I don’t go around here making up a whole lot of stuff. I paint exactly the way it is and exactly the way I see it.” [2] Let’s rephrase the previous question: why does an artist who is considered primitive and who considers himself a realist choose to give up perspective?

This question leads us to a complex subject, that is, the reception of Pippin’s work during his life and in the decades that followed his death. We know that Pippin was included in Masters of Popular Painting. We know that he was considered a “Negro primitive” or “naive artist,” not only by the curator at MoMA but by more or less all of those who wrote or said something about him back then. Judith E. Stein, one of Pippin’s biographers, writes that the term “primitive” was used to describe “such diverse arenas as early American limners, French and Italian thirteenth-century painting, African art and artifacts, Northwest Coast Indian art, and contemporary unschooled artists.” [3] The meaning of a term in a given historical moment gives insight into that historical moment, and this is what I intend to explore in respect to Pippin.

Here is a list of exhibitions in which Pippin’s work is included. Their theme is clear from their titles: They Taught Themselves, American Negro Art, American Primitive Painting of Four Centuries, The Negro Artist Comes of Age, American Primitive Paintings, Twentieth Century Folk Art, Four American Primitives, Four Delaware Valley Primitives, Two Centuries of Black American Art. As to European exhibitions, they include Le Monde Des Naïfs and Naiveté in Art. The term “primitive” and all its connotations are hard to die. They show only two arguments for the inclusion of Pippin in any show at all: the African American among other African Americans; the (presumed) primitive among other primitives.

Pippin was born twenty years after the Civil Rights Act of 1866, which guaranteed citizenship and some rights to African Americans, but died ten years before the fateful day when Rosa Parks refused to leave her seat on a bus, marking the symbolic beginning of the Civil Rights Movement. The reception of Pippin’s work is inextricably linked to “racial politics of artistic visibility,” [4] to use an expression by Cornel West, an African American intellectual who currently teaches philosophy at Harvard and is a former Professor of Religious studies and director of the Department of African American Studies at Princeton. West’s essay on Pippin in the 1994 Philadelphia catalogue contributes to the critical reception of the artist and raises important questions.

The art of Horace Pippin poses grave challenges to how we appreciate and assess artworks in late twentieth-century America. A serious examination of Pippin’s place in art history leads us into the thicket of difficult issues that now beset art critics. What does it mean to talk about high art and popular culture? Do these rubrics help us to evaluate and understand visual artifacts? Is folk art an illuminating or oxymoronic category? Can art be more than personal, racial, or national therapy in American culture? [5]

These questions are still vital today, in and out of the American context, and I dare say beyond issues of racism. But let’s stick to Pippin: why was he, and perhaps still is, considered a popular painter? Why primitive?

West writes that Pippin’s paintings are the expression of a “rich Emersonian tradition in American art” aimed at the analysis of the humble and everyday life – Ralph Waldo Emerson here is the transcendentalist and abolitionist philosopher who helped build a new American consciousness in the 19th century and who fought materialism by exalting the moral forces of the individual. Through some examples, West demonstrates how the art world of those years privileged a self-taught African American artist over the academically educated African American artist, confirming a racist attitude that categorized black artists as “primitive” and “exotic.” This attitude even became a problem for African American schooled artists who could no longer find exhibition opportunities. For this and other reasons, the categorization of primitive and self-taught prompts critical discussion when delving into the art of Horace Pippin.

West specifies that Pippin is an artist who was fully aware of what the white public expected from African American art, an artist who knew how to weave an elaborate game of identity masks within his works.

Instead, Pippin’s art suggests that black people within the white normative gaze wear certain kinds of masks and enact particular kinds of postures, and that outside the white normative gaze black people wear other kind of masks and enact different sort of postures. In short, black people tend to behave differently when they are “outside the white world” – though how they behave within black spaces is shaped by their battles with self-hatred and white contempt. [6]

Pippin not only escapes from the white gaze, but also from the internalized white gaze of African American people. He does not make protest art, nor does he adhere to black art as an expression of the “New Negro”, as West calls it. Pippin’s approach to race seems unconditional instead.

What about the art of the “New Negro”? For Locke and many other critics from the Harlem Reinassance, explains West, there existed a folk art that was raw material and fuel for the erudite African-American artist to create the artistic expression of the “New Negro.” White and Western forms would still have to be applied to this raw material in order to create new expressions. Jazz music and its occasional need to be elevated to “more noble spheres” [7] counts as an example.

West ultimately describes the context in which Pippin finds himself exposed as a primitive not only to the judgment of the white gaze, but also to the aesthetic theories of African American intellectuals. This term in relation to his work surprisingly persists today, no matter how disguised, mystified, or sweetened it might be.

We only have few but poignant testimonies of the way Pippin talked about his work. For example, he said: “Pictures just come to my mind and I tell my heart to go ahead.” [8] A commonplace? Only for those who take the value of spirituality and transcendence for granted. Pippin used an intimate language, which could be considered naive by some but spiritual by others – unfortunately the former interpretation has so far prevailed. Elsewhere he described his artistic process in detail, implying that he was perfectly aware of what he was doing.

However, Pippin is considered primitive, a term traceable back to Vasari yet only by those who don’t understand what Vasari really meant by it. This is a dangerous and elusive categorization, accepted in its veil of feigned elegance and erudition, still misused in the art world. Moreover, it should be noted that “primitive” doesn’t equate with “primitivist,” which instead is a historical-artistic term linked to a precise tradition, and greatly simplifying, linked to all those artists who reference primordial aesthetic languages.

The Pippin case also helps problematize the definition of the self-taught artist, another classification that still exists today and should be questioned. The word is still very much in vogue, especially among American criticism, according to which the self-taught painter is still the individual who has not been taught to hold a pencil and brush in a school. [9]

In contemporary criticism, the word “self-taught” is often used alongside “outsider” and “folk,” despite the three terms have very different or even opposite meanings. Outsiders are those who work in the artistic field outside schools and movements. Folk or popular are those who work in the context of traditional art from a specific community or territory. Self-taught are those who learned on their own to manage a technique, or to develop their own. The etymological significance of these three words does not include any of the disturbing and commonplace drifts of today.

An outsider, folk and self-taught artist doesn’t have to be Kaspar Hauser, or illiterate, or suffering from a psychiatric disorder. Moreover, an artist can be an outsider, folk and self-taught, or one of the three, by choice. In short, the self-taught is not the amazing victim of a lack of education, but an artist with a singular biography relating to the development of a proper technique. This could be any artist indeed. To be cynical, self-taught artists very often end up being victims of any academic education they might decide to get.

In the end, we must be really careful not to give undue importance to the simplifying classifications of primitive, self-taught, outsider. They are widely consumed categories today, only capable of forcing admirable artists like Pippin to become heroes within the field assigned to them by someone else.

To see this, let’s take The Holy Mountain, a series of three spiritualist paintings dedicated to verses from the Book of Isaiah, which Pippin had already seen in an 1833 work by the Quaker artist Edward Hicks. Pippin portrays a shepherd in the likeness of himself, surrounded by the animals of Creation: cheetahs, wolves, bears, children. In Holy Mountain I and III, soldiers and crosses can be spotted among the trees, which Pippin himself mentions as reminders of WWI and the segregated American south.

Next to the artist’s signature, each of the three paintings bears the date of a key event of WWII: D-Day (June 6); the attack on Pearl Harbor (December 7); the atomic bombing of Nagasaki (August 9). They are paintings of great purity, with overpowering chromatic rebounds: the dark skin of the children and the bison is lighter than that of the bear and the wolf; the white of the pastoral dress, shining like the bark of the birch trees; the zinc yellow of the cheetah, Africa, lying in a central position, sovereign and placid like the unicorn with the lady in medieval painting.

Confronted with these works, we can’t deny that Pippin was a pioneer. Today some would perhaps dare write about him that dreadful phrase often found in contemporary painting reviews: “somewhere between abstraction and figuration.” Some people called him primitive, but he was a realist. His reality transcended their own.

Notes

[1] The same day I looked up things like “oil, painting, Bari, 1940” or “Mazowieckie, pastel, artist, 1950s”: a little game of serendipity I still play, as I trust the digital flea market to learn more than anything else.

[2] J. E. Stein, I Tell My Heart: The Art of Horace Pippin, exhibition catalogue, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1993, p. 16.

[3] ibid., p. 11

[4] ibid., p. 46

[5] ibid., p. 44

[6] ibid., p. 49

[7] ibid., p. 51

[8] www.nga.gov/education/teachers/lessons-activities/counting-art/pippin.html

[9] Following this definition, I wonder if those artists attending the coolest art schools in Europe and Italy especially, doing little except sitting in circles and wondering about the nature of art, should be considered self-taught.

April 12, 2021