At the tender edge of violence: Fin Simonetti

Spaces of worship constitute a fruitful field of inquiry for Fin Simonetti due to their symbolic value and particular function, that is, of public places that harbour and feed collective beliefs

“There’s a park in Manhattan near Union Square; it’s a beautiful park. There’s a huge spiked fence all the way around it, and a locked gate.” Only those who own an apartment close to it – that is, real estate – “have the key to get in.” Security, safety, comfort and protection, together with the symbols and beliefs that signal them, affirm themselves as a quiet, consistent conceptual presence across the work of Fin Simonetti. To her, such principles represent “the first layer” of human violence. In the artist’s imaginary, however, there’s no gore nor shock to be found. Instead, Simonetti’s cosmology softly treads in “places of ambiguity” by being grounded in the investigation of those slippery, ephemeral or subtly imprinted notions and norms that are used to define the way people should be, live, or think.

The work of Vancouver-born Fin Simonetti is interwoven with what she calls “a thread of violence,” a non-explicit factor that, running across a diversified, labor-intensive artistic practice as a subtext, silently unfurls through her iconography. Simonetti’s observation of masculinity, male identity and gendered performance – topics she’s been exploring extensively, across a variety of outputs – is tinged with empathy and compassion. Such features, rather than being by-products of a condescending gaze, emerge from the material quality of her works, as her Cathedral series or the exhibition Pledge reveal. The artist’s personal history played a significant role in the development of her perspective on the theme. “My dad died in 2016, and I was estranged from him for most of my life. There’s the loss of growing up without a father, and then there’s the loss of losing a father. There’s two layers of loss, impacted together.” Crucially, her sculptural approach manages to embrace an inner fragility by navigating complex feelings of alienation, which are originally determined by the act of looking at the pain of “contemporary masculinity” as a cisgender female, and have been ignited by “the double loss of a paternal figure.”

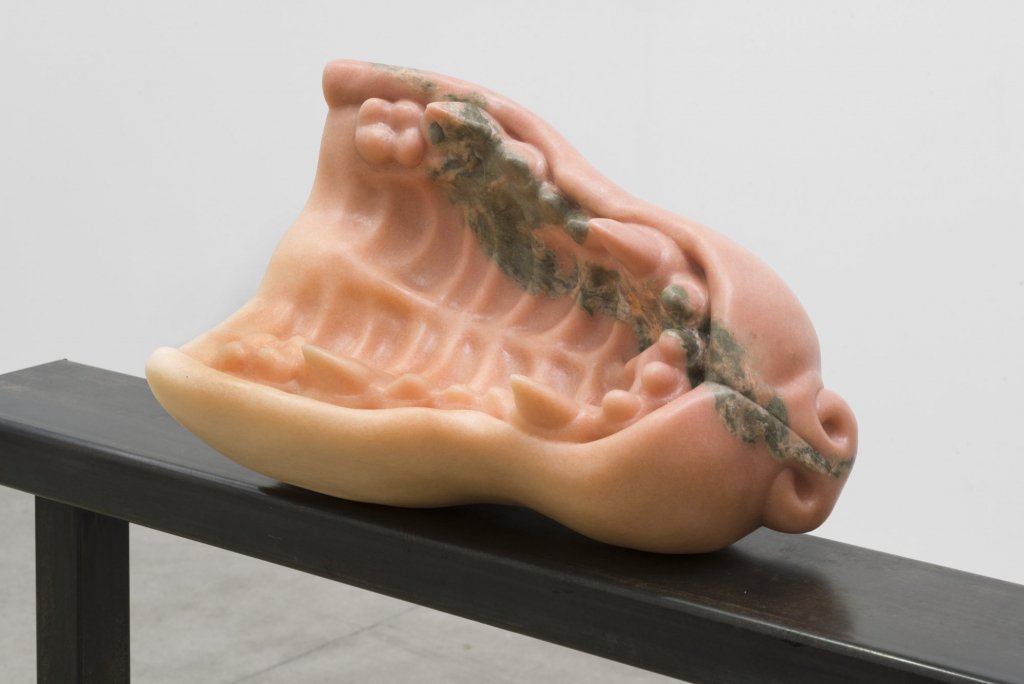

Within her research on the nuances of human violence, Fin Simonetti chose to linger on the study of a specific non-human creature, the pit bull, painstakingly inspecting its form through stone carving, a medium she began to test in 2017. “Animals are my entry point into thinking about people,” the artist states. Historically, they have been exploited in tournaments and gambling, as well as performance and blood sports, including hunting, bullfighting and dog fighting, chiefly as tools of masculine power and prowess. As the artist observes, the way we treat different animals – “right down to the sub-breed” – says a lot about how we interact with the world, and is a telling sign of the brutality inherent in our culture. To Fin Simonetti, the pit bull “epitomizes that.” She mentions how dogs are the animals we most identify with: “we take them into our houses, we let them sleep in our beds, we dress them up; they’re completely anthropomorphized.” Yet there are “certain breeds we made decisions about,” which are enforced through breed-specific legislation, as in the case of pit bulls. “In Colorado you can’t have a pit bull; it’s illegal. They’ll put them down if you have one.” In light of such a framework, supremacy and dominance emerge as explicit features in human behaviour. An animal can be a proxy as well as a weapon.

[In regards to the condition of stray dogs in Mexico City here is a link to our essay about Berenice Olmedo. Ed]

Across millennia, non-human creatures have often represented a path to transcendence, a way to reflect on the human condition; at the same time, they’ve been serving as scapegoats for our suffering and guilt, ultimately becoming “an extension of our own power” through subjugation. Interestingly, vulnerability and wounding are present throughout Simonetti’s universe as in that of Sylvia Plath (1), whose work the artist deeply admires and has referenced in one of her tracks, titled The Colossus. In Plath’s Pursuit, masculine passion, desire, dominance, and violation also coalesce in the figure of an animal, the panther. Written in 1956, two days after she met then-husband-to-be Ted Hughes, the poem exemplifies Plath’s prescient inquiry into the cultural ambivalence of sexuality and power. The piece – overflowing with somatic metaphors and allusions to the erotic – appears to parallel the artist’s conception of the animal as a tool, and extension, of human tyranny and greed, pointing to an atavistic culpability, and summoning sacrifice as its inescapable consequence: Insatiate, he ransacks the land / Condemned by our ancestral fault, / Crying: blood, let blood be split; / Meat must glut his mouth’s raw wound (2).

In Fin Simonetti’s work, the dichotomy expressed by the conflict between “the body that is a threat” and “the body that is threatened” is persistently at play. For instance, “pit bulls” – the artist elaborates – “are actually more dangerous because we treat them that way. You’re more likely to get attacked by a pit bull because you’re more likely to run into one that’s been mistreated, used for dog fighting, and brutalized, so it kind of perpetuates itself.” To her, however, it’s about thinking how the same thing happens in other circumstances. “You can only push any creature so far before it absorbs that violence and becomes a weapon – an actual threat to you.” Fin Simonetti effectively puts into perspective the social, political, historical and biological implications of the relationship that ties the two principles together – which, through her art, cease to appear antithetical. In fact, they end up standing right next to each other, like “opposite sides of the same coin.”

Another concern of Fin Simonetti, which is inextricably linked to the previous antinomy, pertains to the delineation of space and the demarcation of property. Taking into account the wider discourse surrounding marginalization, borders and barriers to entry, Simonetti brings attention to the ways spaces are partitioned, policed and controlled on a daily basis, and how different contexts – through implicit or explicit regulations, or simply by their designation – condition human behaviour. To the artist, “space, and access to space, is this really subtle marker of autonomy.” From the display of her sculptures, as in her solo shows at Matthew Brown and Company Gallery, to the scripts of her performative work, like when she secretly hired a bodyguard to shadow her during the opening of Lifemorts at Interstate Projects, or in the music video for Daughters, her sense of spatial awareness is informed by how barriers and devices actualize “the separation of private from public space, of inside from outside.”

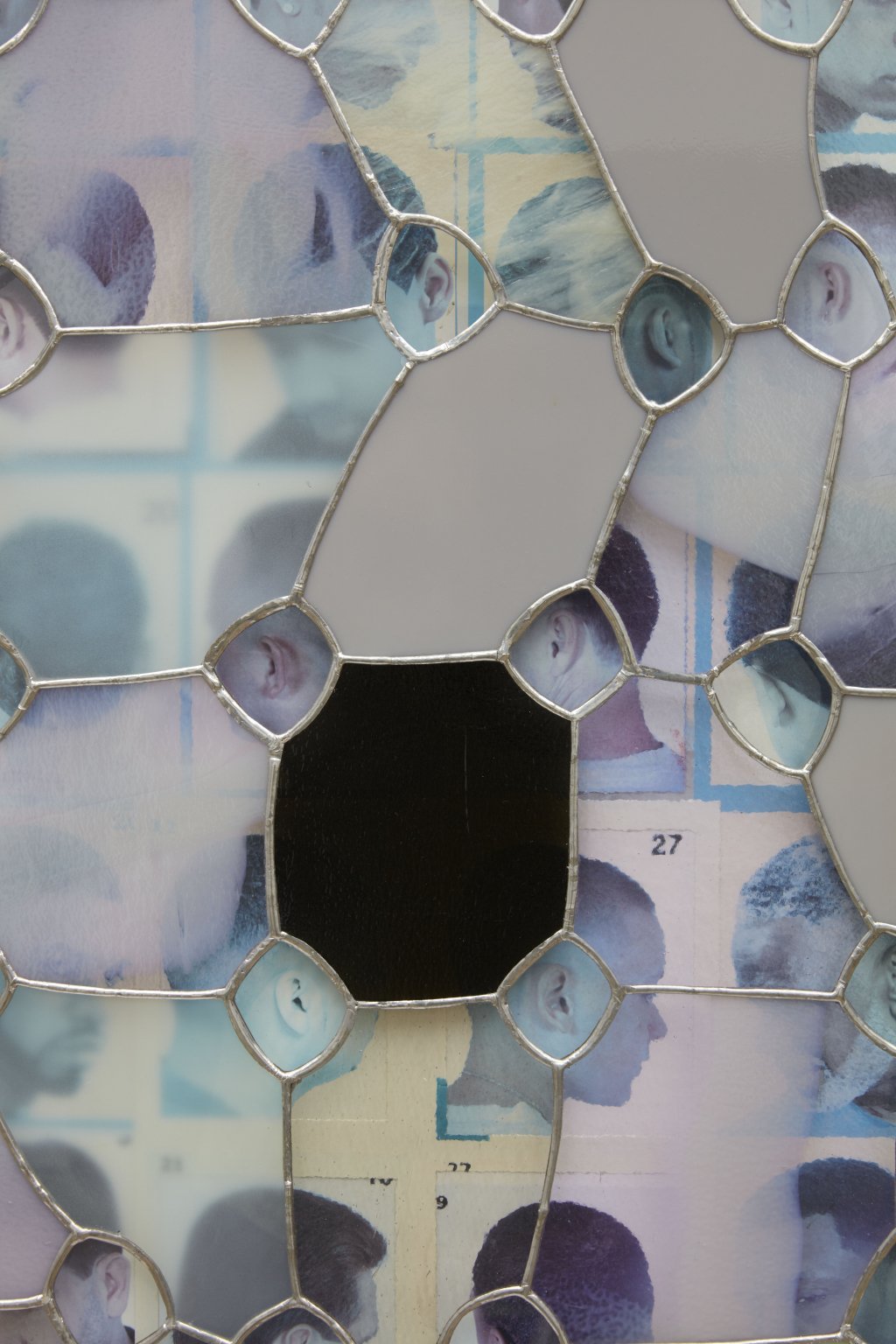

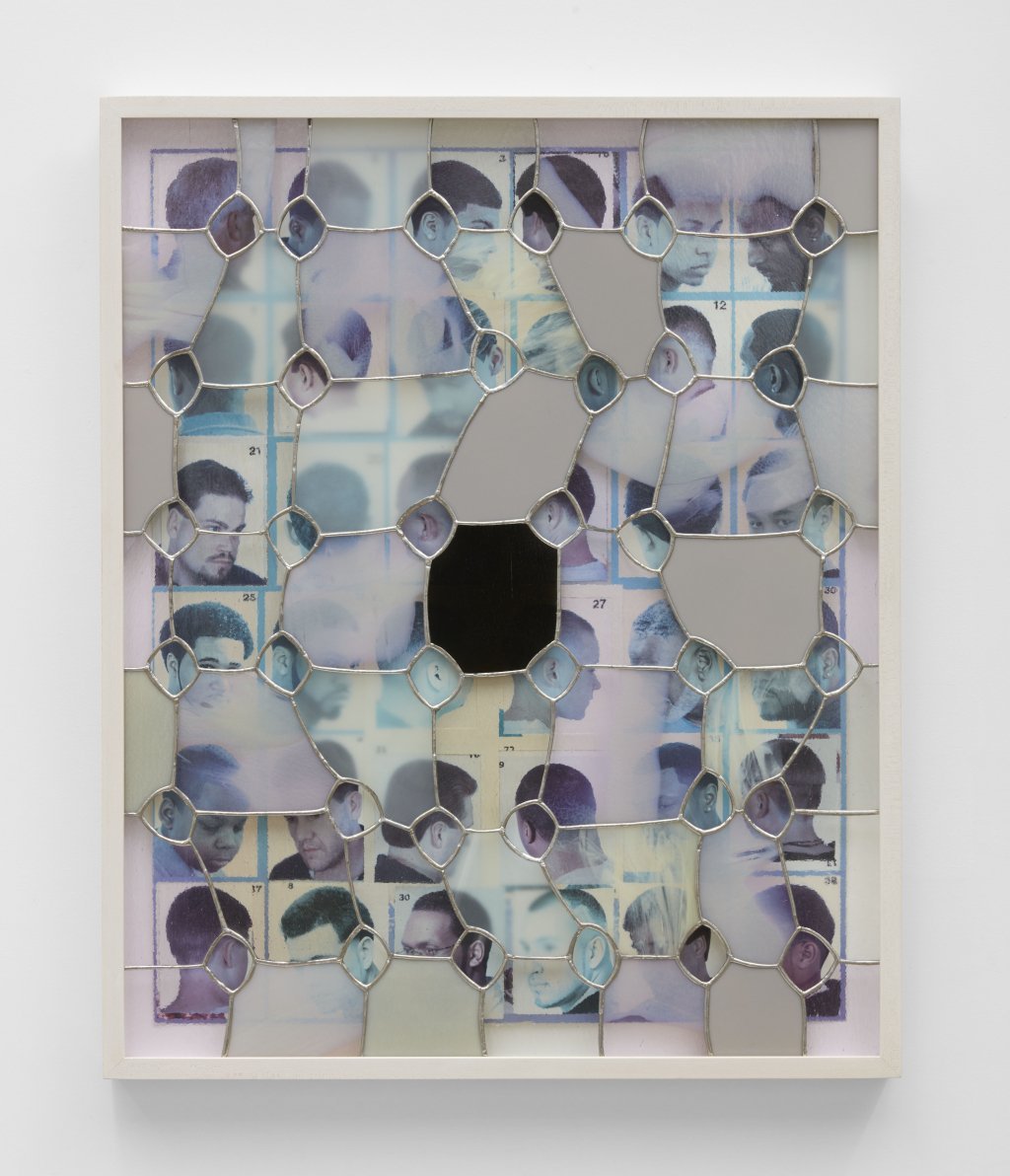

This threshold’s conceptual core finds further substantiation in Fin Simonetti’s stained glass pieces. More precisely, it is the combination of glass and stone – as well some of her shows’ titles, like An Appeal to Heaven, Pledge, My Volition – that evokes a sense of sacredness in her work, conveying a tension to a higher power or will. Spaces of worship are a fruitful field of inquiry for Fin Simonetti due to their symbolic value and particular function, that is, of public places that harbour and feed collective – but intimately held – beliefs. Her interest, she says, resides in “the idea of a sacred place that, architecturally, signals the onset of communing with a presence that’s not corporeal or material.” A cathedral, or mosque, or synagogue, or other sites of worship, and “the words that go in there, the images there,” cue to a distinct way of ritualized thinking which, prior to being religious, is abstract and metaphysical – “a through-line” spanning centuries of “spiritual and religious narratives.”

Rituality surfaces with a certain continuity in the repetitiveness of the artist’s choice of materials and techniques: in the case of stained glass, it was one of her uncles who taught her. When her father’s family immigrated to Canada from Italy, stained glass became their trade. Since she was estranged from her father, Fin Simonetti grew up with her mother on the other side of the country. “After I graduated from undergraduate I had some ideas for stained glass works that I wanted to do,” she recalls, “so I contacted one particular uncle, and said: I want to learn your craft.” She apprenticed under him when she was twenty-three. That became her way “to bridge, to connect” with her ancestry. Today, Fin Simonetti recognizes that quietly doing the same thing over and over again – which she loves – is somehow cathartic, and that repetition is key to achieve depth of understanding. Still, she believes that ascribing value to the “grueling process” of her labor can be “a way to comfort myself about how hard it is.”

Music, on the other hand, holds a completely different purpose to her. “There’s this Joni Mitchell quote where she says like, as she works in different materials, rotate the crops. And music really feels like that.” Simonetti’s second album is about to be published, and it will come out under Hausu Mountain, the record label that published her first, Ice Pix. But she actually sees music as a hobby – it is, for her, a way to decompress, an intermission between the hard labor required by her other media. “It’s a pleasure-based thing, supplemental to making art in terms of creative process.” Then, when people ask her “what kind of music do you make?,” she says it’s “experimental pop.” The fun of it, she adds, “is getting to do something completely unrelated” to her work. “There’s a sort of cohesion, I think, if you’re a practicing artist, in the work that you make – a sort of natural, narrative progression” that unfolds “through materials and ideas.” The stuff she makes in relation to music? “It can be literally anything. It’s a sort of get outta jail free card: do what you want.”

Fin Simonetti records the “little melodies” that pop in her head – usually when she’s walking the dog, after being in the studio – using the Voice Memo app. “I have hundreds of these silly little sound bites,” she jokes. Sometimes one of them will stand out to her, or get stuck in her head. “That’s when I go to the computer and start recording, building on things slowly.” Alternatively, she cuts a sample from a specific source that will eventually become “the kernel.” “Recently I sampled these church bells. I pitched them up an octave higher, so their sound comes out glitchy and higher, and looped them. And then from that a whole song came up.” The artist stresses how in her music there’s no concept. “People can make music like that, but I don’t. There’s no thesis. It’s soft and playful.” Whilst Fin Simonetti’s art making is “pretty vigorous” in its conceptual structure, requiring intensive journaling, writing and research in the planning phase (which she’s currently undertaking to prepare her next show at Cooper Cole, scheduled in March 2022) her music just isn’t. And because of its immateriality and its time-based nature, music cannot be compared to sculpture, drawing or painting. “It’s not planned – it happens in the moment.” Plus, it can be experienced anywhere. “Music is in your home or in your headphones. It’s very personal and banal, and that’s exciting. It’s sort of un-academic and un-ritualized. It has that balance. It’s expressive, open, and intuitive. Maybe it feels like dancing.”

(1) David M. A. Francis, Here Be Monsters: Body Imagery in the Poetry of Sylvia Plath (2018), p. 130. Source available at this link.

(2) Sylvia Plath, Ted Hughes [ed.], The Collected Poems (1981), p. 22. New York: Harper&Row.

April 18, 2024