Henrik Potter: HINGE

The work of Henrik Potter is not the in-between. It is more the and and. It’s a mutuality, a literal enjambment

Attached

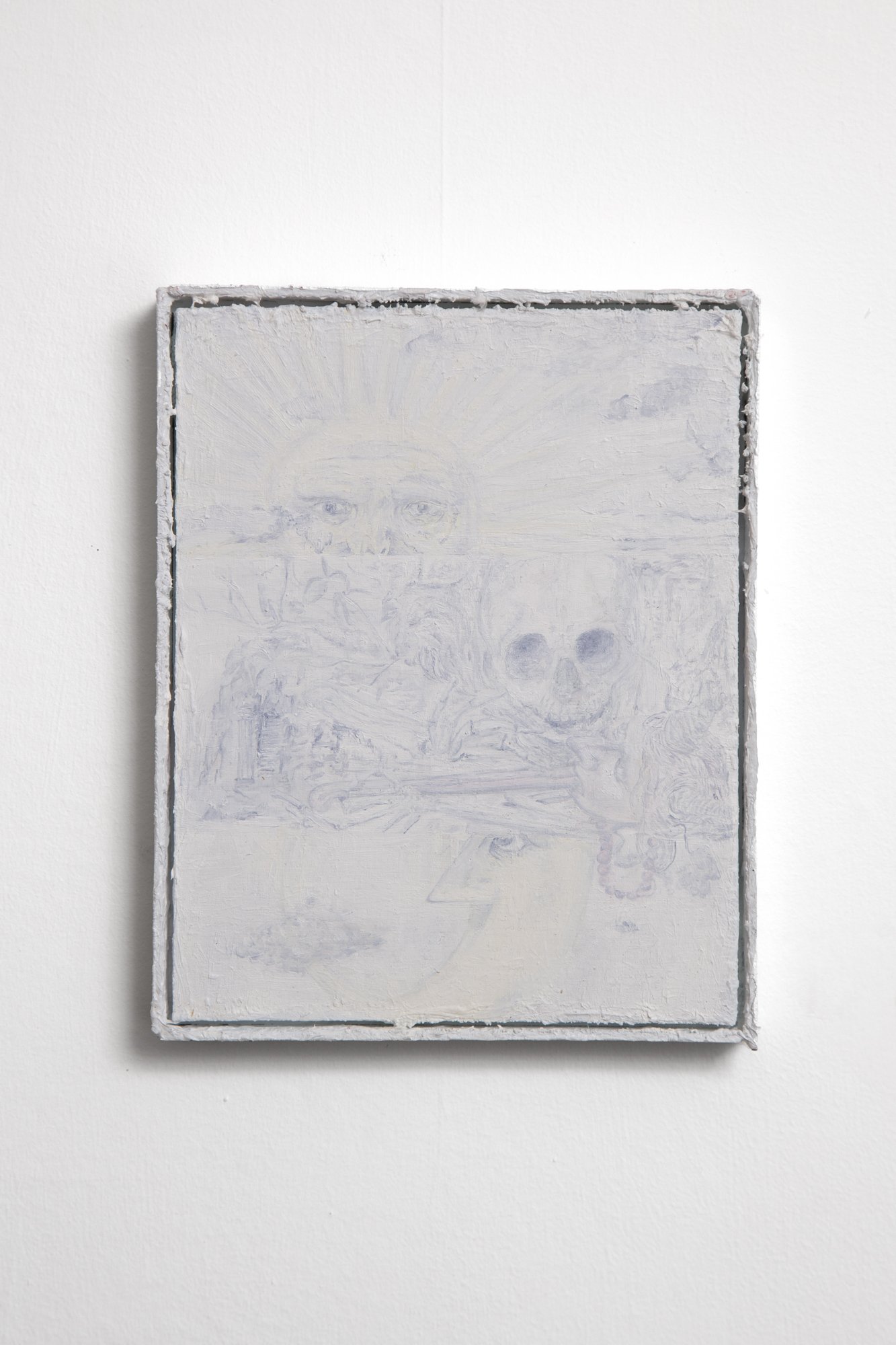

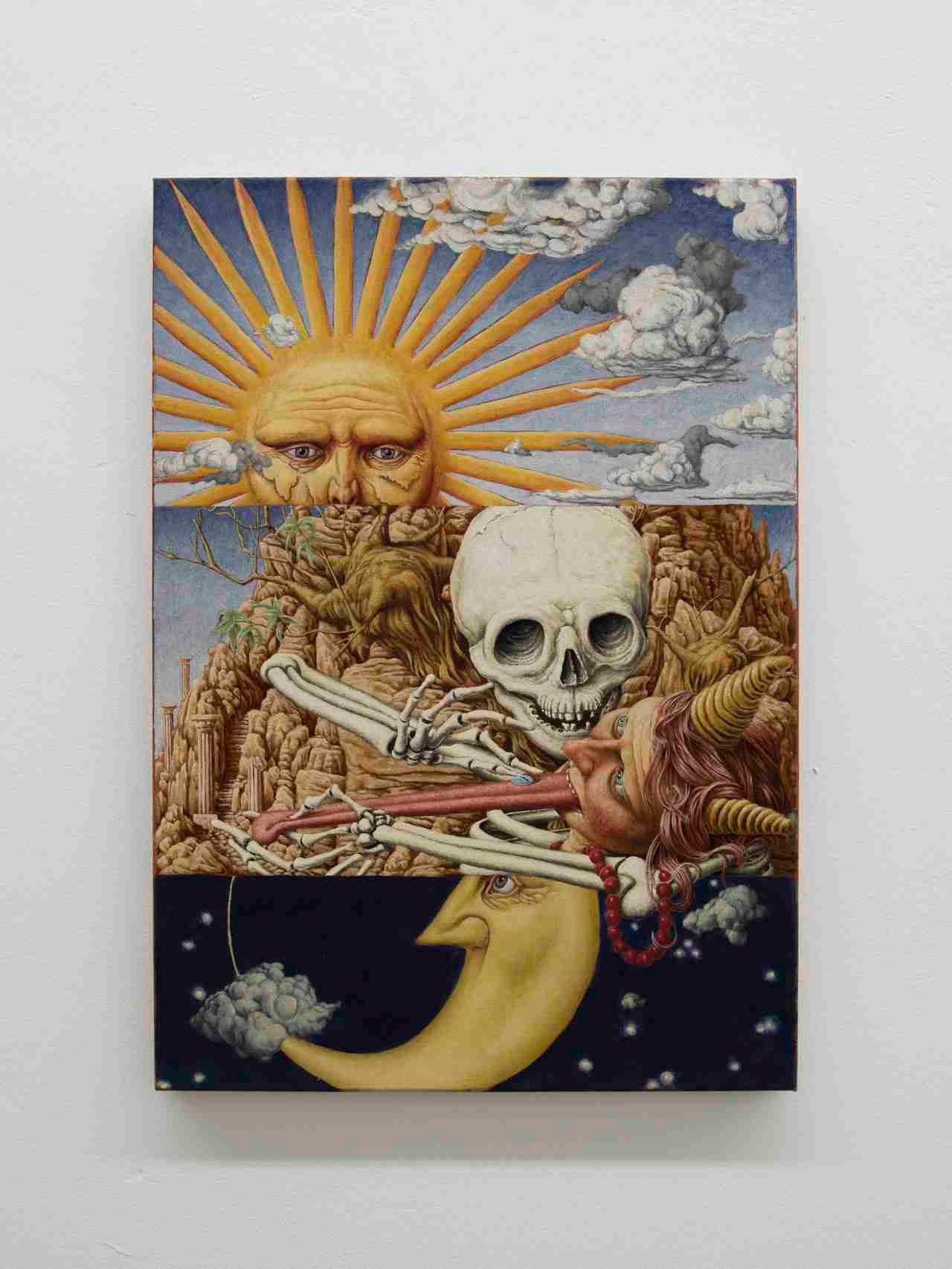

Let’s not call them windows. Let’s call them hinged works, and then other ones small paintings. The large ones are muslin, rather than canvas. The plywood edges of the small painted reproductions, give you blister splinters.

The work of Henrik Potter (1984, Lausanne) consists of drawings, paintings and objects— yet he seems to approach all his makings as the making of a thing; rather than a surface. In what he likes to refer to as fuck ups, the artist’s hand is found in contact traces — Potter nicely says to find greater goodness by doing things badly. The impulse to make the small paintings or the hinged works is similar, using lateral problem solving. They are, in all their differences, made to be in each other’s presence, poisoning and contaminating each other a bit. The impulse? Sadness, grief, love, fuzzy feelings.

Not just presenting the good side, but all sides of his “things”; Potter plays with scale, direction and the relation to the viewer’s body. Everything comes back to the body at large, the size of a hand, and fingerprint. Each of these are sequentially considered in a little patch of hand-stitching, in more than human sized stretched muslin and his small ongoing series of appropriated images.

Bodily qualities

Henrik Potter’s oil on wood series, bare references to other artist painters, and the doubting viewer is kept on track with titles like ‘…with apologies to Jannis Marwitz’ or ‘…with apologies to Philip Guston’. Looking for a readability and a representational element, Potter felt that using imagery and borrowing feelings and ideas second hand— he says some people have done a very good job at it before me. The paintings are the size of hands. There is an absorbing quality to the imagery, largely due to the way they are painted, images that wait to sharpen, sleepy eyes looking at a screen waiting for brain fog and eye mucus to make lift. Or the screen turning red on a Wolfenstein 3D game when you’re killed, eyes filling will blood, you can feel it. Decapitated heads in a melancholic syrup, stem from an interest in place of slight discomfort all the works spring from; somewhere between greatness and failure, between underbelly and thinking beast. In the interaction lies the gist.

[Here is a link to pur writing about Jannis Marwitz. Ed.]

Trying to find a way to hide the staples that keep the muslin stretched on wood, a mixture of glue and clay became a way for every little spot of the works to have been handled, touched. In the small paintings it’s the splintered plywood that gives scale and texture; infra-connections in the work to relate to itself and its viewer in size. And colours are felt as temperatures, fades, decisions.

Slightly larger than a person and standing on two ‘legs’, the only real connection between his 45 odd large works for his 2019 show at the Künstlerhaus Stuttgart is their format. First presented like paravents in space, the large free-standing panels hold the middle between textile sculpture and painting. The surface seems textured with touch, details of dotted/dashed lines, or sudden detailed paintings the size of an eyeball, keeps moving the gaze. Whether these are the small paintings, looking at Potter’s work feels like sitting in darkness waiting for the image to clarify. There is a stillness that moves, in images inserted and cut off in mysterious detail, in the coexistence of soft and rough, in clay leftovers of grabbing. He rope-skips with the medium of sensing painting.

In his most recent exhibition at Sundy’s in London, the person-sized hinged works are suspended using a monitor hanging system, a tireless stretched arm, that presents them elegantly into the space. The muslin-covered frames open up using a mechanical bearing that connects two solid objects, allowing different angles of rotation between them. The panels indoors are warm colours, the one work outside holding a candle and thus actual heat is black. What he calls generosity is to support the viewer’s impression and comfort that the work justifies asking to be looked at, for that he uses laborious effort, time and size. The panels open and move forward and sideways, like a performer projecting to a big hall of viewers. Manipulated by the visitor they shift shape as they do medium. Oddly sturdy in our minds, it feels like looking at one image, one contained whole, in one shape or the other; but Potter is beyond us.

And the palindrome of being an artist

Working consciously from a place of discomfort, unsure whether what he just made is very good or very bad, he embraces both, looking for a form that has to hold itself. It’s what you could call an attitude of loving conflict, in which time and scale as parameters of solidity and trust, which opens up a new space for looseness. Potter chooses to work with the material rather than overruling it, it can be neat or messy, sub ideal works too. Mistakes in his practice are there to balance out other perfections. There is a coupling quality, of transaction almost, to works being open and simple. But there are also many headless bodies, not necessarily violent, just left altered in reality. The work itself, he notes, becomes an ersatz body for the artist.

This honesty, and transparency seems to seep through the entire practice of Potter. It feels like a child nibbling at the old paint sticking out of a Philip Guston, a woman correcting her hair before moving a piece of furniture. The work of Potter is not the in-between as so many practices have been called. It is more the and and. It’s a mutuality, a literal enjambment. The works are attached bodily qualities, thought in temperatures, agility and recognition. Dots like seconds like time passing. Large or small like effort. Subjectivity as the dialectical tension between positions; bracing.

November 24, 2021