Kyle Thurman: beyond the night’s philosophy

A departure from history’s headlines, a lucid dream of armored giants: a comprehensive essay on the art of Kyle Thurman

Glory and gore go hand-in-hand. They paint headlines and, together, produce history. What else is history but a fluttering image of the here-and-now, the flit of what Walter Benjamin calls a “memory as it flashes up at a moment of danger?” In its haste, history forgets all about the world-to-come. Casting the future further into doubt, history demands allegiance from its parade of soldiers, those monsters and men under our beds; the symbols and representations creeping about in our heads. Does the future only promise history to its armored soldiers, those gilded in glamor? Here’s a hardening and interrupting thought: don’t go looking for yourself in gilded glamor. Instead, train your eyes to touch the everyday. The writer steps back and groans: “enough toiling for today.” The night’s philosophy beckons him to bed. He lies down and shuts his eyes. He enters the dark and his vision vanishes into sleep. So, when he falls asleep, where do we go?

***

Lately, the artist Kyle Thurman has been roaming around in the dark. He’s painting the stuff of our dreams. The works titled Dream Police (all 2022) depict armored giants frozen in technicolor nightscapes. The suited giants come in pairs, meeting chest-to-chest or back-to-chest, captured from the waist-up and eyes-down. They’re all shoulders, breast, spine, and wings adorned in bright, berry-colored coverings. In Dream Police (Your wings) a giant’s shoulder fades from lemon-to-lime green. It follows behind a larger comrade whose armor is painted raspberry red and orange, calling to mind the much-decorated, genderful Power Suit of Nintendo’s Samus.

Looks often lead us astray, whether it’s the toxic dayglo of a granular poison frog or the bright plumage of a bird of show or prey. Conspicuousness progresses synchronously with noxiousness. From the backside of the warm-hued giant emerges a holographic magenta aura (its titular wings): a bravura blossom, foreign matter, and energy in motion. The wings seem to be alerting predators of immediate unprofitability.

Many of Thurman’s Dream Police paintings have a slightly weathered, fuzzy feeling to them. Dreams and drawn ideas diminishing into impermanence. The works are fabricated by mixing dispersion pigment, gouache, oil, and watercolor on jumbo wood panels. The application of water-soluble pigments onto a wooden surface nods at thwarted attempts to recall night wanderings. Dreaming is the kind of repeated activity that cultivates language’s and the body’s inwardness, vulnerability, and uncertainty. A dream’s eddying indeterminacy is a reminder that tools like language and the body regularly fail us.

Each Dream Police work measures 48 inches by 72 inches (121 x 183 cm) and is outlined by a unique artist’s frame. The work’s dimensions evince a quality at once celebratory and familiar. Bigger is better—these are some of Thurman’s largest works as of late—but, its specific dimensions also pay homage to at-home movie projectors, which proliferated during the recent COVID-related lockdowns. Projectors are now a staple household appliance, both affordable and able to cast higher quality images. Peek into your neighbor’s apartment window and you might just catch a cast of armored superheroes, minions, and villains on walls in roughly the same dimensions as these works.

Beyond the artist’s drive to conjure up characters of a certain size, he’s also motivated by the abundance of body armor that clouds our off-white bedroom walls. Figments of body armor from the Marvel Cinematic Universe, like Tony Stark’s Iron Man suit, Captain America’s electromagnetic exoskeleton, and Thor’s battle armor appear in several works. In other works, there’s perfunctory references to the extraterrestrial-plated robot foreigners, the Autobots and the Decepticons, from Michael Bay’s Transformers series. These giants appear closer to the picture plane as if a single-player soldier in a story mode video game locked in immortal combat.

Thurman has something to say about these cast of soldier-like characters: “In the earlier months of the pandemic, like most people, I was spending a lot of time on social media. Instagram, TikTok… A fandom of people who 3D print and customize their own fantasy body armor flooded my algorithms. Marvel superheroes, most frequently Iron Man, and characters from popular video games.” The (proto)fascist male body has been depicted as a machine that is both a tool and weapon since the aftermath of World War I. It’s no coincidence this is around the same period as both the beginning of the armored superhero and villain in illustrated comic books and at the culmination of the disfigured body in the dadaist and surrealist movements. The age of mediated sociality.

Freud belaboured that the traumatized soldiers and battle-afflicted populations from war (women, children, etc) marked the return of something dreadful. Particularly, he stressed, it was the return of the repressed. This was a condition of the socially and/or sexually distressed as illustrated by the Dadaist and Surrealist artists. Perhaps, then, the sculpted, aposematic armor of superheroes and villains diagnoses the treatment of the male body as a machine engineered “as a ridiculous weapon and impossible tool,” as the art historian Hal Foster has posited.

[For more on post-war trauma, repression, and armors, here is our essay on the art of the Matthieu Haberard. Ed.]

If that’s the case, let’s keep building. War and discord show us that the original scene of trauma is the fascist father’s anger over the disruption of his desire for a well-oiled machine. Whether that machine is his child or the child’s mother is moot, the disruption of loyal intimacy in his production (or, reproduction for those that can) induces a state of “fragmentation, disintegration, and dissolution.” Is this everything that the armor seeks to protect us from?

Nearly a century later, Thurman notes: “Today, we see people constantly employing readily available technology in an attempt to transcend lines of power, from digitally manipulating the image and information around one’s identity to 3D printing firearms. The fantasy body armor and the exoskeletons illustrate the desire for control, power, the Crown, and for the human body to have the ability to endure repeated conflict.” As a record number of mass shootings and war crimes continues to rattle headlines around the world, is it any wonder that the technology and production of 3-D printed guns and armor has never been more obtainable? We can all be armored soldiers now.

The artist prefers his figures to fraternize under a veil of armored ambivalence. In the foreground of one painting, Dream Police (My breast), a heavyweight dazzles with its ice-blue chest and main-character candor. At the right edge of the panel another behemoth emerges, caught in a hazy purple and cherry soda background. Across its lower face and chest flicker three splotches of neon green. The splotches resemble hi-tech motion-activated light sensors, a collision detector, or an emerald heat map. The green could be sounding an alarm or signaling discontent, an attack on the giant’s mechanized nervous system by the approach of an intruder. While the background giant breaks free from the depths of the painting and confronts its other, it’s unclear what will happen next. Does the green light announce a battle? Or camaraderie? An invitation to fellowship?

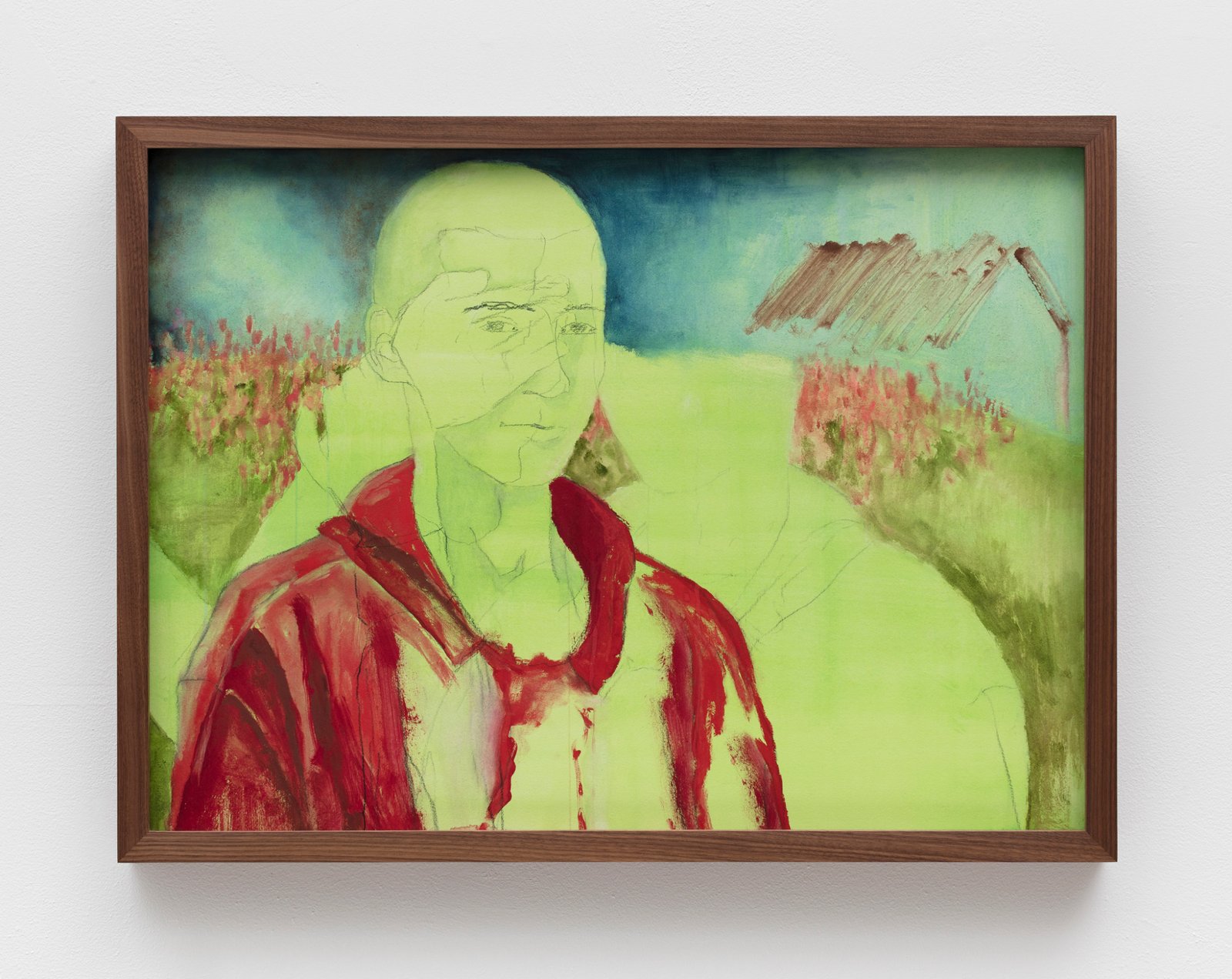

Narrative inaccuracy, arbitrariness, and ambiguity creep into much of Thurman’s work. In effect, the artist configures an anatomy of sociality, often homosociality, only to expose its historical inarticulateness. Men are always worn out. Consider his most recognizable series to-date, Suggested Occupation (2015-2022). Using a blend of charcoal, ink, and pastel, the artist renders boys and men as either line drawings or smudged watercolors on colored paper. He details estranged boys and men entangled in conflict. Boys touching boys and men touching men.

Sometimes the boys are locked in fist fights or gathered in scholastic assemblies; at other times they hold one another close in sleep. It’s glory and gore, the stuff of a Dennis Cooper novel or an angel baby’s wet dream. When Thurman was a teenager his parents and guidance counselor advised him to become a soldier, an athlete, a clergyman—to find an institution that would nurture a career in compulsive homosociality. Since then, he’s culled images from magazines and newspapers of these figures, the same kinds of boys and men who make headlines. Who knew that a touch is just a touch too much?

Thurman grew up in Chester County, Pennsylvania. During the feverish and fertile season, he was surrounded by white-tailed deer, eastern cottontail rabbits, crickets, katydids, lightning bugs, and cornfields. In colder months, the landscape thinned out to reveal crumbling barns, barren trees, and sour milk white skies. These ingredients are the skin and bones of Andrew Wyeth’s pastoral paintings of Pennsylvania and New England. What Wyeth’s paintings reveal is a psychic disarray, the wavering states of homelessness and nationalism at the heart of much American mythology. This is especially true ever since the outset of our post-agricultural era. In Thurman’s Suggested Occupation series, he shares something of Wyeth’s American Realist vocabulary.

For Wyeth, though, one’s own backyard becomes a site for depressive guilt, the kind of feeling that washes over us as we watch a woman in pink apparel crawl on stiff arms and twisted legs through a yellow field towards a lonesome-looking wooded estate. The painting in mind, Christina’s World, (1948), is a touchstone of American Realist painting. It exemplifies the dawn of the post-agricultural human world regressing into a state of detachment and dissociation from its land and its people. Part of this is due to ecological and social disasters of manifest destiny, another part from the corroding belief in the American Dream. Suggested Occupation’s tone shares a similar conviction. We are most naked when we are athletic, and still clothed, in our failures.

Another beloved motif of American Realism is youth. Thurman attended an all-boys Catholic high school as a teenager. The artist and his guy friends daydreamed about other things than becoming soldiers or priests. This was the early 2000s, the beginning of the war on terror and the admission of the inconvenient truth of the Catholic Church’s sex abuse scandals. Instead, the boys oriented their great escape towards the kind of anti-establishment masculinity offered in movies like The Fast and The Furious franchise or The Matrix and its sequel. These flicks proved that fast cars and freaky pills could be useful catalysts for starving off fumbling institutions.

Through the decades, cinema proved to be Thurman’s surest gateway to get away. “One day in high school Spanish class,” he recalls, “the priest teaching the course showed us Pedro Almodóvar’s Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown—it totally blew my mind.” The carnival of colors and beautiful people, the embrace of the hedonistic and ludicrous aspects of social and sexual life—Almodóvar’s film made an incision in Thurman’s bucolic everyday. “He told us not to tell anyone that he showed it to us. Then I started buying DVDs with all my money at the Chester County Bookstore, they had a big international section. It was a paradise for me.” He would go on to attend Columbia University earning a degree in Film Studies and Visual Arts in 2009. Afterwards, he studied drawing with Christopher Williams and Peter Doig as a student at the Kunstakademie in Dusseldorf.

Eventually, Thurman found another paradise, this time in painting. There’s something particularly arousing about his armored giants sauntering through magnetically charged dreams, captured in covert encounters, painted by the hand of a professional dreamer. While the armor represents a multi-dimensional erotic energy, the dreamscape that encompasses their encounter thwarts the conventions of narrative logic. Dreaming renders null and void things like courage and conquest, plot and setting. There’s no straightforward path for the dreamer.

Who exactly is the dreamer in Thurman’s Dream Police paintings, though? In addition to the two armored giants convening in each painting, a third figure exists. The third figure lies recumbent, also waist-up and eyes-down, between the two giants. In Dream Police (Your wings) and Dream Police (My breast), the figure appears as a solid cut-out, an underpainting surely on its way to become “the” sleeping dreamer referenced in the title of the paintings. The sleeping is reminiscent of a shooting target silhouette, an anonymous and nearly illegible signifier of whatever quiet thing it should represent to be penetrated.

***

Several of the dreaming interlocutors are blurrier masses, all-engrossing apparitions of deep unconsciousness, like the midnight purple splotch in the bottom-left corner of Dream Police (My spine). Are Thurman’s dreamers the conduits, or the idling police, of these sublimated scenes of static desire?

The writer turns over in his sleep. His dreams slowly stir him to wake. Night’s philosophy has delivered dreams that must now be acted upon. He opens his eyes. He stretches out his fingers and turns-the-page. He touches a new day.

May 19, 2023