On Kim Farkas’ vesical sculptures

Kim Farkas pursues the Kantian idea of the manifold forming a unity as a concept that leads to pleasure (and the first edition of Paris +)

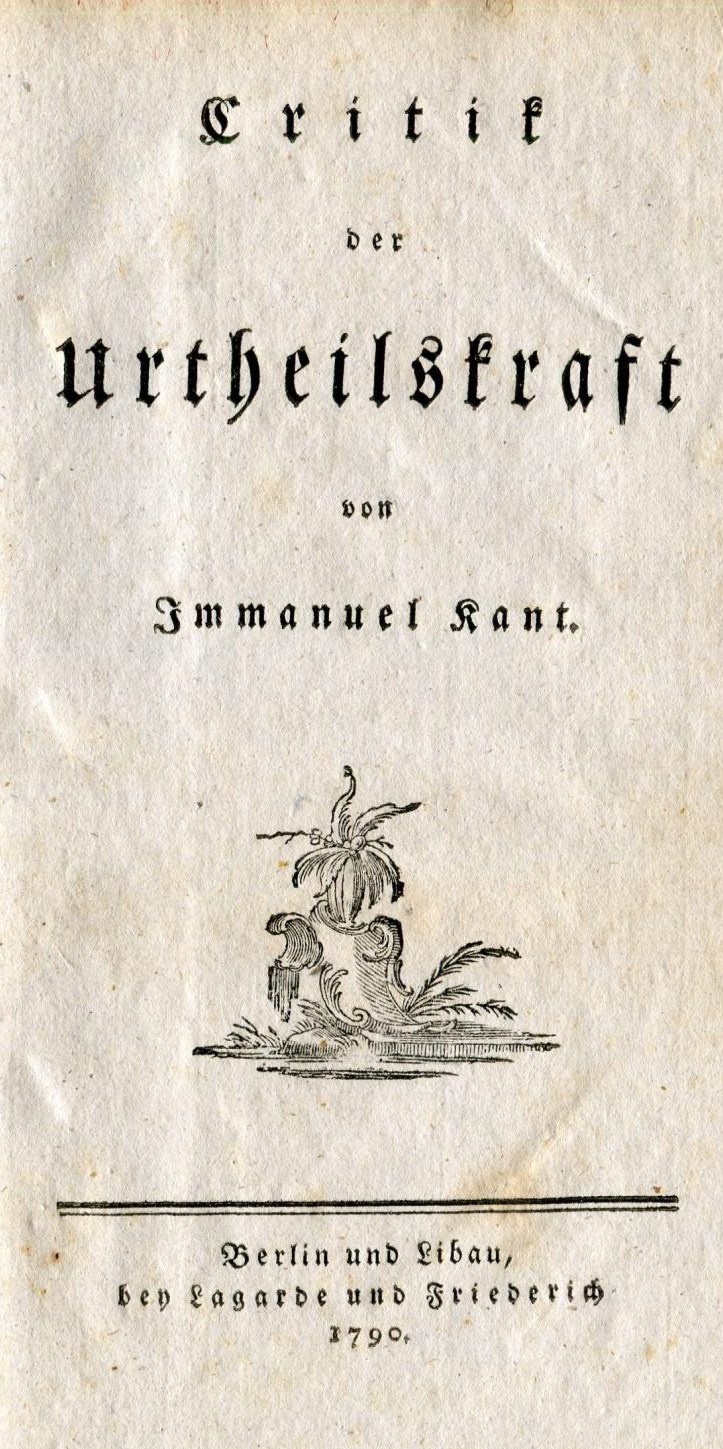

After meeting Kim Farkas (born 1988, based in Paris), one realizes how an artist can be deeply immersed in the present. Yet, the 230 year-old Critique of Judgment by Immanuel Kant offers two passages that say more about his luminous vesical sculptures than what we could possibly do. Let’s take a deep breath and jump back over two centuries in the history of ideas to observe that:

1) If the harmony of [something] manifold to [form] a unity is to be called perfection, then we must present it through a concept; otherwise we must not give it the name perfection. [1]

2) An aesthetic judgment is one in which the basis determining it lies in a sensation that is connected directly with the feeling of pleasure and displeasure. [2]

Take the first statement: if you have been lucky enough to handle the Farkas’ pieces, or have seen him at work, what strikes is the perfection with which its parts are assembled together, down to the smallest detail. In contemporary art, perfection often bears a negative connotation, which can nonetheless change to something praiseworthy if it becomes an expressive element, i.e., it becomes the imprint of those “clear and distinct ideas” (to put it as Kant did) that are the foundation of the sublime. We know how much Picasso, an artist whose work has been considered perfect in his own way, despised Raphael’s precision. This does not mean that Raphael ceases to be a master, or Picasso is not to be considered a perfectionist. Two contemporary artists such as Olafur Eliasson and his pupil Tomas Saraceno also tend to formal perfection in respect to mastering the plasticity of light; Farkas follows a similar research path.

Raising the bar to the level of the mind and looking at the narrative in Farkas’ vesical sculptures, the elements of its general poetics converge into the “unity” mentioned by Kant. The objects that constitute his sculptures–selected first, drowned in epoxy resin after–are excerpts from a conversation centred around his persona, a story that promises to remain open to the intellectual evolution of the author and his environment. Farkas has Peranakan roots, a South Asian ethnicity whose long and complex history granted the opening of a dedicated museum in Singapore. The distance of his “perfect” works from the type of executive perfection typical of industrial production becomes a reflection on his life story. The agreement of the multiple in unity–concept merges with form–becomes evident in his “vesicas.”

Let’s look at the second Kant statement mentioned above. Like lamps, Farkas’ pieces contain a light bulb that, when on, illuminates the resin-fixed objects of the main body; these are things found in the many Chinatowns of the world or 3D prints of the artist’s own designs. They come alive with light, sparkling reflections and, especially when they alone illuminate what’s around them, causing the kind of visual pleasure Kant might have referred to. (Think of the candle on the table, a lighthouse in the night, the stars in an unpolluted sky.) Clearly, the idea of artistic beauty has greatly evolved since Kant wrote his Critique of Judgment, and so has our aesthetic judgment. Displeasure does not necessarily lead to negativity; some artists even start with such feelings to change the nature of the beautiful. Today, few would question Picasso for the same reasons that he was questioned–even considered revolutionary–in his time. What is beautiful is replaced by what is expressive; a contemporary taste for Central African masks, Matisse’s paintings, unfinishedness, and unrestored furniture that has made the fortune of an astute dealer like Axel Vervoordt attest to this change.

For Farkas, the pursuit of the pleasant is as bold as it is functional. As in the early seventeenth century European Caravaggist paintings, he uses light to reveal, and like Eliasson or Dan Flavin before him, he builds a symbolic space with it, a location that evokes distinctive features of a composite culture. Like the art of his friend Naoki Sutter Shudo, with whom he founded the publishing house Holoholo Books in 2015, Farkas’ vesical sculptures exist to represent, functioning as if they were figurative paintings extended into the third dimension. However, if for Sutter Shudo light is only suggested (a street lamp in his piece does not really turn on), Farkas means for it to happen in real life; he includes electric wires, switches, plugs, bulbs, or anything else that serves to carry light, to turn on his vesical sculpture not so much like a lantern as like a firefly.

On the occasion of the first edition of Paris +, as part of the projects conceived for the Jardin des Tuileries, Farkas will present his first outdoor work. The sculpture is titled 22-20, meaning his twenty-second work of 2022. The choice to title the works following a sequential numbering is a way to underline the logic of consequentiality to which his works respond. They are organic entities that evolve in a process of bivalent adaptation. On the one hand, as we have said, they change in relation to the poetic necessity of which they are an expression. On the other hand, they adapt to their environment. For the Jardin des Tuileries, Farkas’ sculptural surface thus loses its transparency to become dark, reflecting what is around it instead of allowing a glimpse of what it contains. The light does not cast the shadows of the objects immersed in the “vesica,” but shines through, so to speak, from a harmonic complex of muscle masses. The scale of representation appears reversed: from small to large, from a cellular entity to a structured body. The agreement of the multiple into unity as a concept that again leads to visual pleasure.

[1] Immanuel Kant, “Critique of Judgment”, translated by Werner s. Pluhar. Hackett Publishing Company, Indianapolis/Cambridge, 1987, p. 416.

[2] Ibid. p. 413.

October 17, 2022