Kate Mosher Hall: perceptual limbos and moiré-noirs

A reflection on the not purely painted – but not just printed – canvases of Los Angeles artist Kate Mosher Hall

In the 19th-century, J.H. Brown wrote a treatise on the optical effects of afterimages, titled “Spectropia; or Surprising Spectral Illusions Showing Ghosts Everywhere”, in which he used a detailed anatomical explanation of the eye to debunk the myth that this effect was evidence for the existence of ghosts. But seeing is believing; there is a gap between the scientific explanation of the effect and the experience of it, where something ineffable lurks.

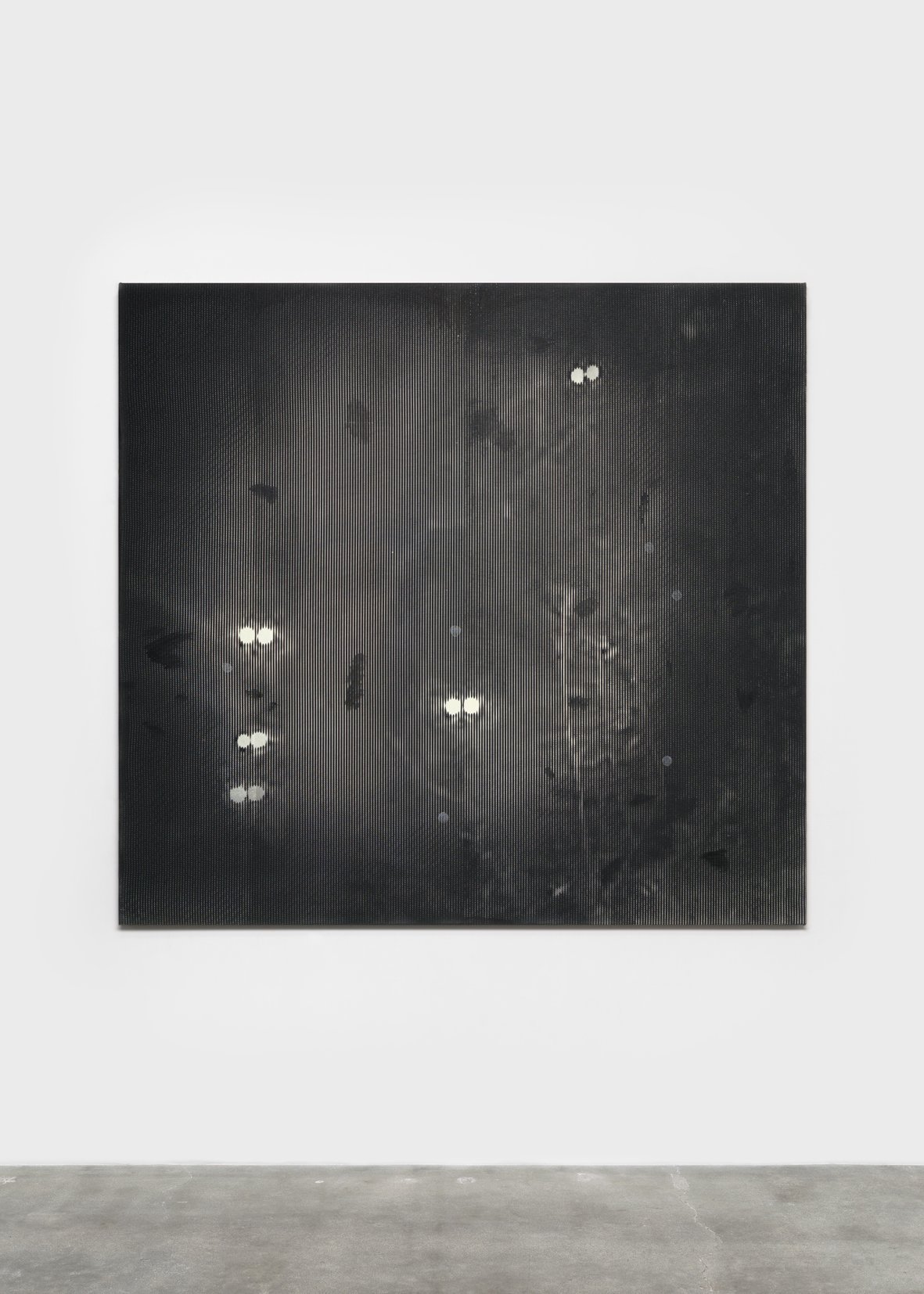

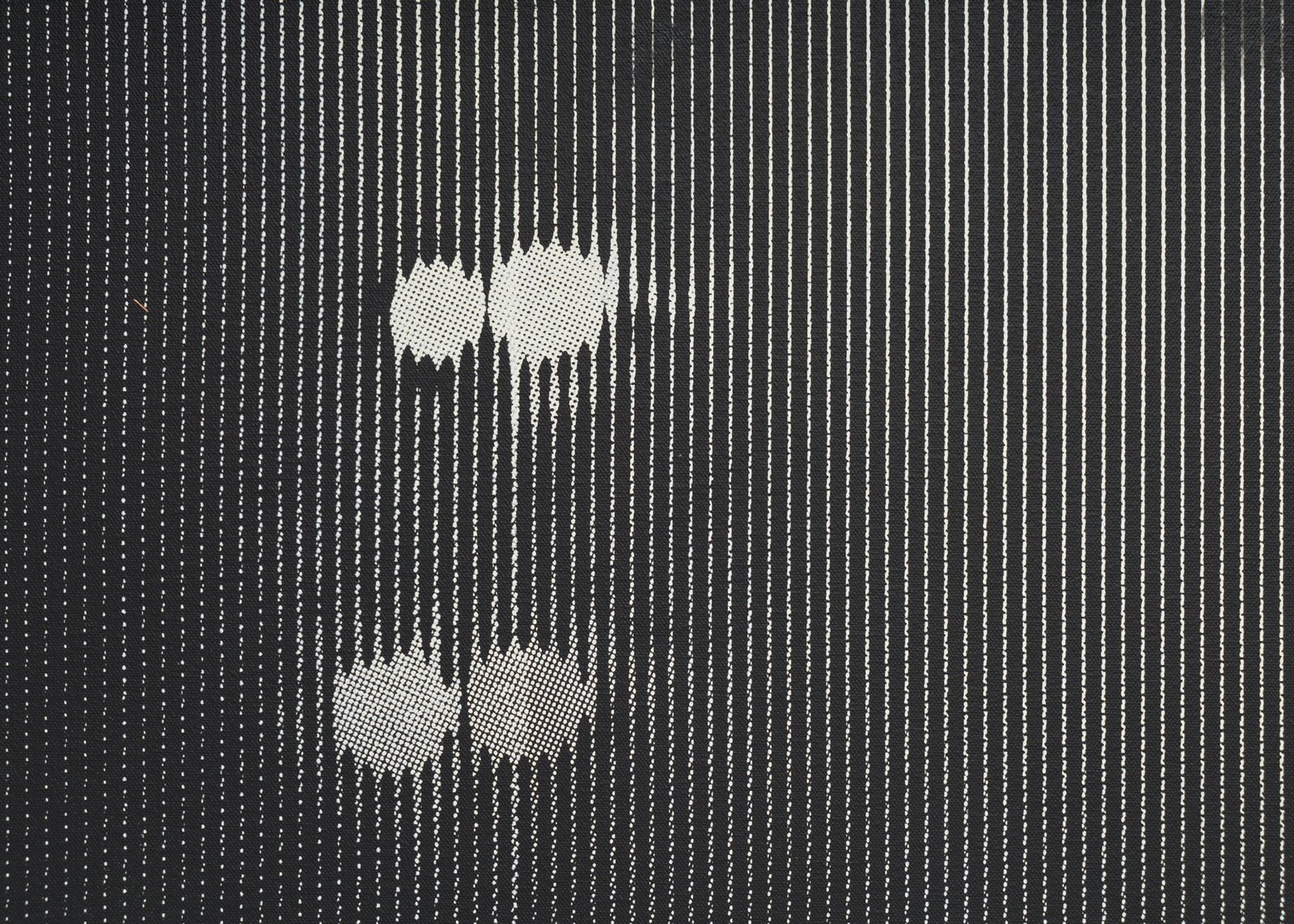

To hear Los Angeles-based artist Kate Mosher Hall explain how she makes her works cannot prepare you for the effect of seeing them. They play tricks on the brain, their different parts revealing themselves according to your proximity. They have the hypnotic qualities of Op art, if it were surveilled through the grain of a CCTV camera. Her works are made by adding successive layers of hand-painted and silkscreened pigment that most often result in canvases of thick and deftly engineered darkness. Important to this process is letting the elements “play out,” [1] as she says, manipulating and constraining chance. Between the control of the brush and glorious accident inherent in printing comes a new kind of surface.

Mosher Hall began playing in punk bands as a teenager and it was through the punk scene that she found her way into screen-printing. Her approach to the medium owes much to the DIY, messy, radical, and humorously irreverent aesthetics of punk: the ways it turned appropriation into a re-creative act. She produces works that are not just printed, but not purely painted: she is instead something of a paintmaker. Disrupting the negative to positive of the printing process to create double negatives, you are not quite seeing what’s not quite there—this is a play of known unknowns and unknown knowns. The paradoxes that play out are almost Miltonic when in Paradise Lost the poet talks of “No light but rather darkness visible,” or that which is “dark with excessive bright.” These works create a perceptual limbo as your eyes grapple with spectral figures that peek from behind curtains, dance in the shadows, evade spotlights, blur just beyond our reach. Resolution becomes dissolution, collage becomes obstruction.

There are many profound life events that feed into the making of an artist, things that mitigate and hone the way they see the world and therefore characterise their particular vision. Mosher Hall has, in her own words, one particularly “impactful story”. Eighteen years ago, when attending a punk concert, a gun fight broke out nearby and she was hit by a stray bullet that went in behind her ear and out of her mouth. She recently wrote a very frank account of this event [2] and talks openly about it, but she reflects on it not for its dramatic value but on the way which it caused a tectonic shift in her relationship with the very act of seeing. She passed through the veil and back, and says: “from that moment on I became really acutely aware of the act of looking or of being looked at, how we look through things, and this lead to an interest in what you can and cannot see within a painting.”

She is interested in “activating the viewer in the space” and there is a deliberate attempt to orchestrate, as she says, a “delay for the image to hit” as we try to work out what we are looking at. The mesh of the silkscreen becomes a strategy of concealment and obfuscation; our desire to perceive forms is offset by our difficulty in reading them; instead we must conceive them for ourselves. Her paintings often depict mysterious characters dancing in a moiré-fringed gloom, something of the danse macabre about them, or the ghoulish quality of early animation. She has developed different motifs of obfuscation over the years, torn curtains like perceptual peep shows have morphed into spotlit stages; symbols of an illumination denied.

The poem by Rachelle Sawatsky that accompanied Mosher Hall’s works at Frieze NY contains the line “I like to be lied to about the mechanics of optical illusions.” Her works make expressive use of optical effects that are intentionally challenging to their own digitisation, they resist compression. Many of her latest works use moiré patterns, that glitch that arises when two textured patterns are layered over each other but rotated slightly, creating visual interference on a screen. If you view the works online your screen will struggle.

Many of the works evoke the disquieting atmosphere of a California noir, but the murder victim is a rasterised JPEG, blown well beyond the limits of clarity. We are the confounded detective, left to sift through the dismembered images for the shape of the crime. It is one of the rules of classic detective fiction that the supernatural may play no part in the plot. But what is the supernatural if not our own tendency to layer the phantasmagoric over reality – to see the ghosts in afterimages – compensating for the fact that the simple explanation is never enough. As Mosher Hall says, she wants to create works that are “flirting with reality, but rooted in something that’s not real.” An unwanted gain in the real, these canvases fulfil the definition of the uncanny: strangely familiar and yet ambiguous and eerie. Mediated images become spirit mediums. Between the thought and the act falls the shadow.

[1] All quotes attributed to the artist are taken from a conversation in January 2023.

[2] https://flash—art.com/article/kate-mosher-hall-letter-from-the-city/

March 24, 2023