Lippo di Dalmasio: pop without knowing it

Lippo di Dalmasio degli Scannabecchi painted in series, signed his works and was a self-promoter, like the masters of the US boom

Had he lived a few hundred years later he would have had much in common with pop art. But Lippo di Dalmasio painted between the end of the fourteenth century and the beginning of the next when Warhol and Hirst, champions of a serial art, were still far from becoming. Yet, with them, the Bolognese painter shares more than one aspect. That makes him today a personality to be reread in a contemporary key, marked by fame, shrewd resourcefulness and proud self-awareness; capable, albeit unbeknownst to him, of crossing the borders of his own city and, with a leap in time, appearing on Christmas cards and special editions of Royal Mail stamps: his Madonna of Humility with Angels, the property of the National Gallery in London, solemn rather than gentle, and illuminated by a huge circle of light, this became a regular presence in the Anglo-Saxon domestic hearth centuries after the painter passed away (1).

This is a market strategy that has featured many personalities on the contemporary scene in recent years. For example, Louis Vuitton’s collaborations signed with Yayoi Kusama or Jeff Koons – although in the case of Lippo di Dalmasio the initiative takes place post mortem. The result, moreover, is the same: the fruition of a work of art takes place through its transformation into an alternative consumer good intended for the masses.

The exhibition at the Museum of Medieval Art in Bologna, curated in 2023 by Massimo Medica and Fabio Masaccesi, hosted not only the works of Lippo di Dalmasio, but also coeval sculptural and manuscript evidence, offering the cue to delve deeper into an artist fully inserted into the fabric of his hometown, which consecrated him to imperishable fame as a painter of Madonnas. To such a career, Lippo di Dalmasio is in a sense predestined. His father is the artist Dalmasio degli Scannabecchi, documented between 1342 and 1377 and active in Pistoia between 1359 and 1365 (2). His uncle, on the other hand, is Simone di Filippo Benvenuto, one of the most successful artists of 14th-century Bologna, otherwise known as Simone dei Crocifissi. Lippo di Dalmasio, born at a date after 1350, must have completed his apprenticeship precisely in Pistoia, although his certain works all date after his return to Bologna and were composed in little more than two decades (3).

Following in the footsteps of his uncle, whose nickname derives from his favorite subject, so too Lippo di Dalmasio devoted himself almost exclusively to depicting Madonnas, and especially Madonnas of Humility seated on the ground. With an almost Warholian foresight, Lippo di Dalmasio thus identifies a winning formula and replicates it so as to perfect it and thus satisfy the demands of the patrons: if “Andy” repeated the portraits of celebrities to please them and secure their support, Lippo portrays the Virgin Mary who ça va sans dire is the Jacqueline Kennedy of an era in which the iconography of the Madonna spreads thanks to the presence and theological action of the medicant orders. The strategy proves to be successful and Lippo achieves popularity, not only in his own time, but especially when, in the late 16th century, he becomes a role model for devotional and Marian painting promoted by the Counter-Reformation. Francesco Cavazzoni signs his praise of him in his work: “Lippo dal Massi […] bolognese fu assai valente pittore da quei tempi ed omo esemplare di buona vita e costumi. Non pinse mai cose vane, ma sempre si compiacque in operare per sua mera divozione la imagine de la gloriosa Vergine […]” (4). According to Malvasia’s account, on the other hand, Guido Reni, of whom Lippo di Dalmasio is in a certain sense a precursor, sees in the faces of the Madonnas of the primitive “un certo ché di sovrumano, che gli faceva pensare, il suo pennello, più che da forza di uman sapere, venir mosso da un occulto dono infuso” (5).

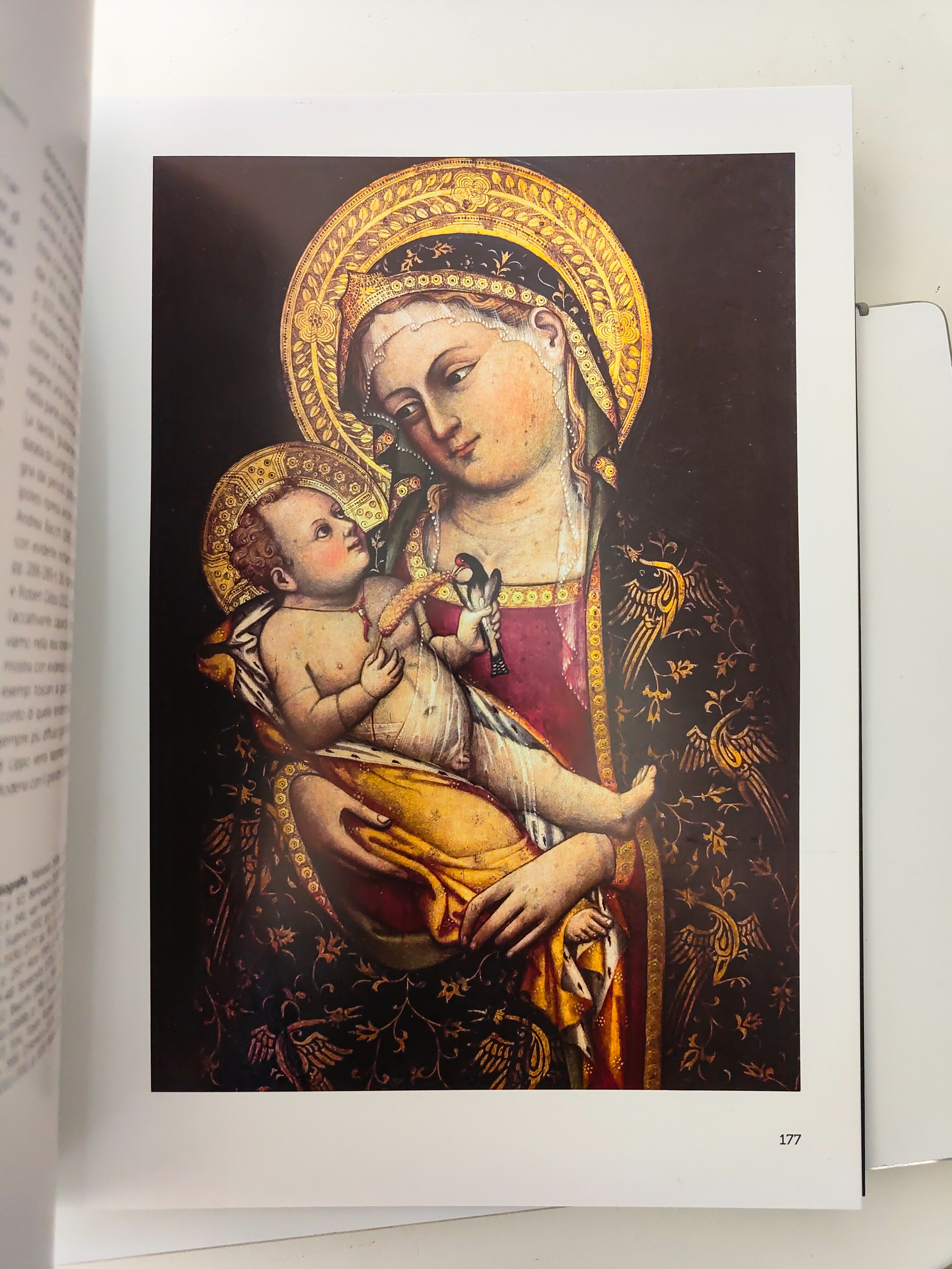

But Dalmasio’s son is not a slavish executor of this theme that was so successful in the Emilian and Bolognese area. In fact, the painter seems to have imported some iconographies hitherto unrelated, such as the swaddled Child standing on the Mother’s legs that we see in the “fake” polyptych in the Basilica of Santa Maria dei Servi. And again the little finger in the mouth of the presence of the goldfinch, as in the Madonna of Velvet on display (6). So called because already in the late 17th century placed on crimson velvet, it is a work of the most successful, spent on leafy nimbuses and soft transitions of the complexions. Its mantle is embellished with rampant griffins, the same heraldic motif we admire on that of Vitale da Bologna’s Madonna dei Denti in the Davia Bargellini Museum. Other variations on the Madonna of Humility theme (7) include the presence of a radiant sun and a flowering meadow. The luminous disk, in addition to the aforementioned Madonna of the National Gallery in London, already appears in a Pistoiese fresco attributed to Lippo di Dalmasio and located in the old refectory of the Convent of San Domenico, known as the Madonna of the Pavilion (8).

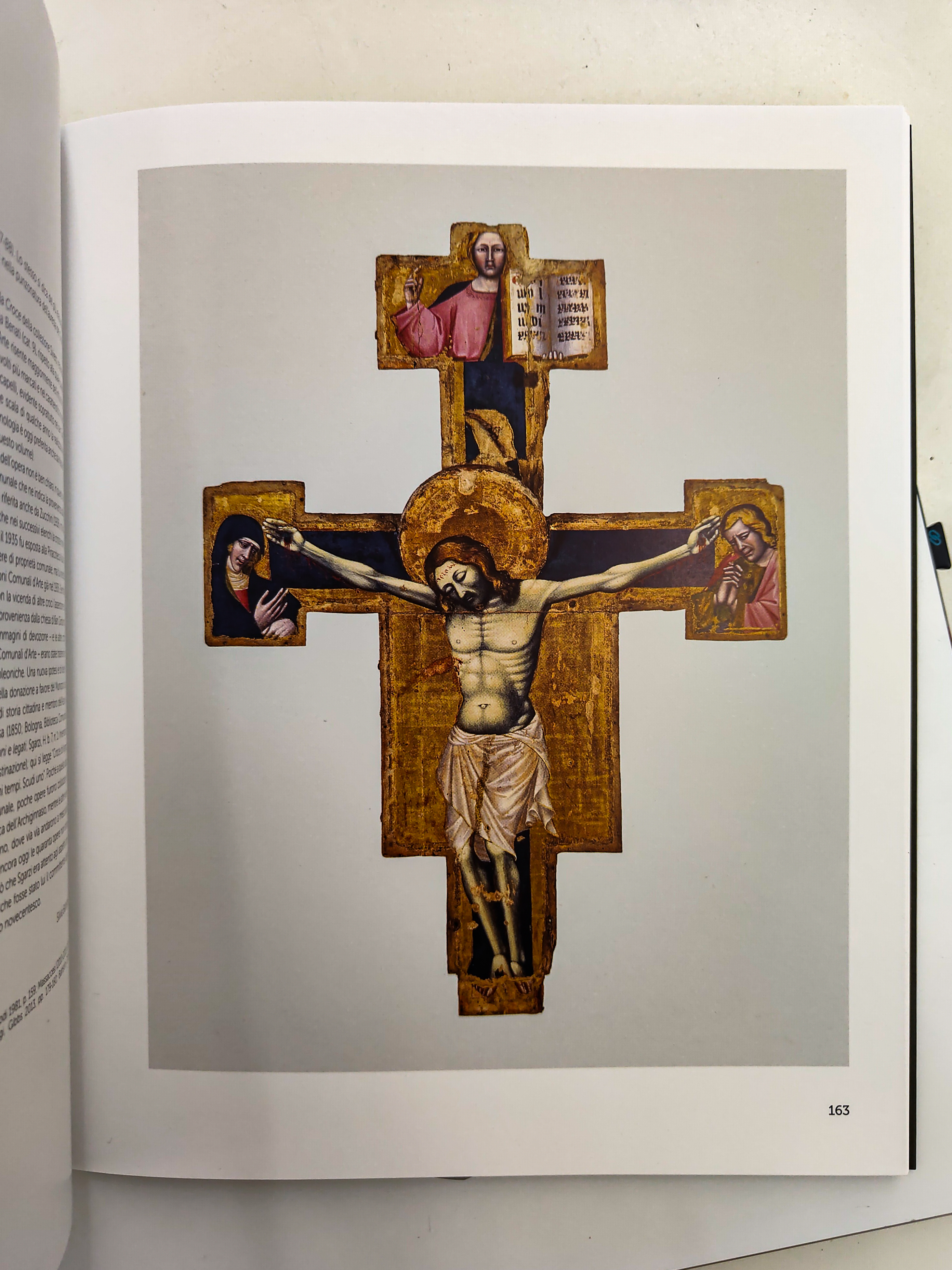

Examples in the exhibition, on the other hand, include the torn fresco from the Church of Santa Maria della Misericordia and the beautiful canvas from the gallery of the Banca Popolare dell’Emilia Romagna. In both cases, the subject of the Maria Lactans, an iconography that originated in the East and spread to the west thanks to Franciscan mystical action (9), is illuminated by a large sun; in the second painting there are other apocalyptic attributes, such as the moon at the Virgin’s feet and the twelve stars crowning her (10). The other element that stands out is, as we said, the lush meadow, a clear reference to the hortus conclusus taken from the Song of Songs (IV, 12) and a symbol of the Garden of Eden (11). Now, the definition of Lippo as an exclusive painter of Madonnas is true but needs to be scaled down. Here are two painted crosses, one of which, after restoration, brought to light, in the lower part of the vertical axis, an earlier painting from the late thirteenth century, almost an ante litteram upcycling operation.

Lippo di Dalmasio, multipurpose artist

If we the move from Bologna’s Museum of Medieval Art to the Pinacoteca, we find a tablet, similar to a biccherna, depicting the Oration in the Garden and Saints Ambrose and Petronius (12). The model of Bologna, held up by the latter, is the most elaborate of the 14th century and in it the two leaning towers and the cathedral of St. Peter are recognizable. The rapidly sketched landscape conveys a certain nocturnal mystery while the simple trees and touches of grass are reminiscent of the lively treatment of miniaturists, a practice that has always enjoyed great prestige in the city of Bologna.

The painting, with a strong civic connotation thanks to the presence of the saints often invoked as patron saints, allows us to shed light on another element that makes Lippo di Dalmasio a thoroughly modern painter: his being polyvalent, or rather, multitasking. In Pistoia first and then in Bologna, in fact, he held various public offices, including those of municipal collector, vicar, captain, castellan, and even notary (13). For those who could write and had a certain level of culture, taking on official duties and cultivating on the side a different activity such as painting was quite common practice. But the data reported bear witness to the fact that Lippo di Dalmasio was able to gain credibility and trust in these fields as well, and by systematically increasing his own real estate holdings, thanks in part to a constant campaign of self-promotion that closely resembles the parable of some names in the current artistic milieu who have become true impresarios. And who perhaps simply affix their signature at the conclusion of the work executed by one of the numerous assistants active in their colossal “workshops.” On this front, too, Lippo di Dalmasio is a pioneer: at a time when signatures on art pieces were rather rare, the gesture of putting one’s name on a piece reveals an awareness on the part of the author of his status, but with the substantial difference that Lippo actually painted his Madonnas, while very few of the most successful contemporary artists can do it.

1. Scott Nethersole, Devotion by Design: Italian Altarpieces before 1500, Londra, National Gallery Co. , 2011, pp. 34-35; sulle edizioni Royal Mail, Lippo di Dalmasio, Flavio Boggi e Robert Gibbs, Bononia University Press, Bologna, 2013, p. 20.

2. F. Filippini, G. Zucchini, Miniatori e pittori a Bologna. Documenti dei secoli XIII-XIV, Firenze 1947, pp. 59-61; Gibbs, Two Families of Painters at Bologna in the Later Fourteenth Century, in “The Burlington Magazine”, CXXI, 918, 1979, pp. 560-568; R. Pini, Il Mondo dei Pittori a Bologna. 1348-1430, Bologna 2005, pp. 55-56.

3. F. Masaccesi, Lippo di Dalmasio e le arti a Bologna tra Trecento e Quattrocento, Milano, 2023, p. 52.

4. F. Cavazzoni, Pitture et sculture et altre cose notabili che sono in Bologna e dove si trovano, Bologna. Biblioteca Comunale dell’Archiginnasio, ms. B 1343; Lippo’s profile as a devout artist famous for depictions of Madonnas also emerges in Malvasia’s Felsina Pittrice when the author states how much “fossero in tanto pregio […] le sacre immagini di Maria Vergine da Lippo Dalmasio dipinte, avendo saputo ei più d’ogn’altro dar loro un’aria così santa e divota” cfr. C.C. Malvasia, Felsina Pittrice. Vite de’ pittori bolognesi, con aggiunte, correzioni e note inedite del medesimo autore di G. Zanotti e di altri scrittori viventi, t. I, ed. Guidi dell’Ancora, Bologna 1841, p. 74.

5. C.C. Malvasia, Felsina Pittrice. Vite de’ pittori bolognesi, per l’erede di Domenico Barbieri, Bologna 1678, vol. I, p. 26.

6. F. Masaccesi, Lippo di Dalmasio cit., pp. 62 – 63.

7. Thanks to the studies of Millard Meiss we know that the first depiction of Our Lady of Humility in a monumental piece is the fresco in the lunette of the portal of Notre Dame des Doms in Avignon, which Simone Martini painted for Cardinal Stefaneschi in 1340. See M. Meiss, Painting in Florence and Siena after the Black Death, Turin, 1982, ch. VI, p. 208..

8. See Boggi, Gibbs, Lippo di Dalmasio, cit., pp. 59-66, 136-137.

9. H. e M. Schmidt, Il linguaggio delle immagini. Iconografia cristiana, Roma, 1988, p. 274, n.39.

10. B. Carmignola, Dalla donna vestita di sole delle apocalissi anglosassoni all’iconografia di Maria Lactans, in E. Simi Varanelli, Maria L’Immacolata. La rappresentazione nel Medioevo. Et Macula non est in te, contributi di B. Carmignola, C. M. Paolucci, Roma, 2008, pp. 62-64.

11. Ilaria Negretti, Lippo di Dalmasio cit., p. 122.

12. On the cult of Saint Petronius in Bologna see, for example, Beatrice Buscaroli (ed.), Petronius and Bologna. The face of a history. Art, history and the cult of the patron saint, Ferrara, Editai, 2001.

13. F. Boggi e R. Gibbs, Lippo di Dalmasio cit., p. 119.

December 12, 2023