The Howard Hodgkin collection of Indian court paintings

Howard Hodgkin approach to collecting had nothing to do with art history. What mattered to him was how each piece affected him emotionally

According to the records, Howard Hodgkin devoured Agatha Christie’s novels. He couldn’t resist an elephant. And, when it came to buying whatever he longed for his private collection, he wouldn’t take no for an answer. The late British artist has explained that much of the motivation behind a collection can be attributed to a single concept: desire. But once that stage is surpassed and the collection’s character is formed in the owner’s mind, the pieces must be acquired “out of necessity, as well as passion.” During a talk that Mr. Hodgkin gave in 1992, he announced flatly: “A great collection often seems to be the result of one very rich man going shopping. It isn’t. It is really partly illness, an incurable obsession.”

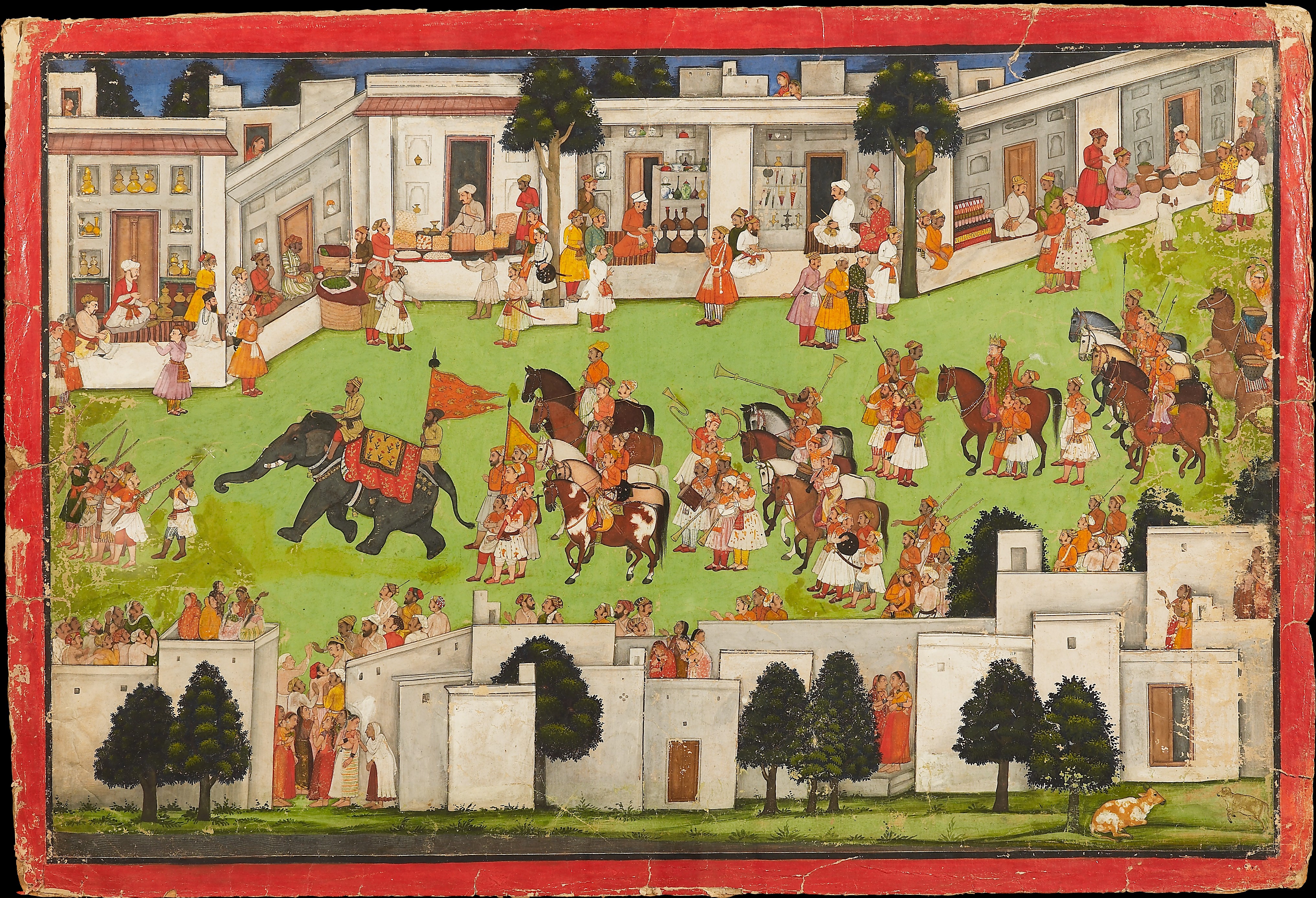

Howard Hodgkin’s compilation of Indian court paintings was acquired in 2022 by the Met Museum in New York. The exhibition that followed, “Indian Skies: The Howard Hodgkin Collection of Indian Court Painting“, offers a comprehensive look at a group of artworks that spans Mughal, Deccan, Rajput and Pahari pictures dating from the 16th to the 19th century. There are epic and court scenes; portraits of maharajas and dervishes; botanical and zoological studies; hunting, bathing, weddings; and a room devoted entirely to elephants, many depicted with the same introspective approach human beings’ representations typically take. Also, it seems that the artist loved to identify with elephants.

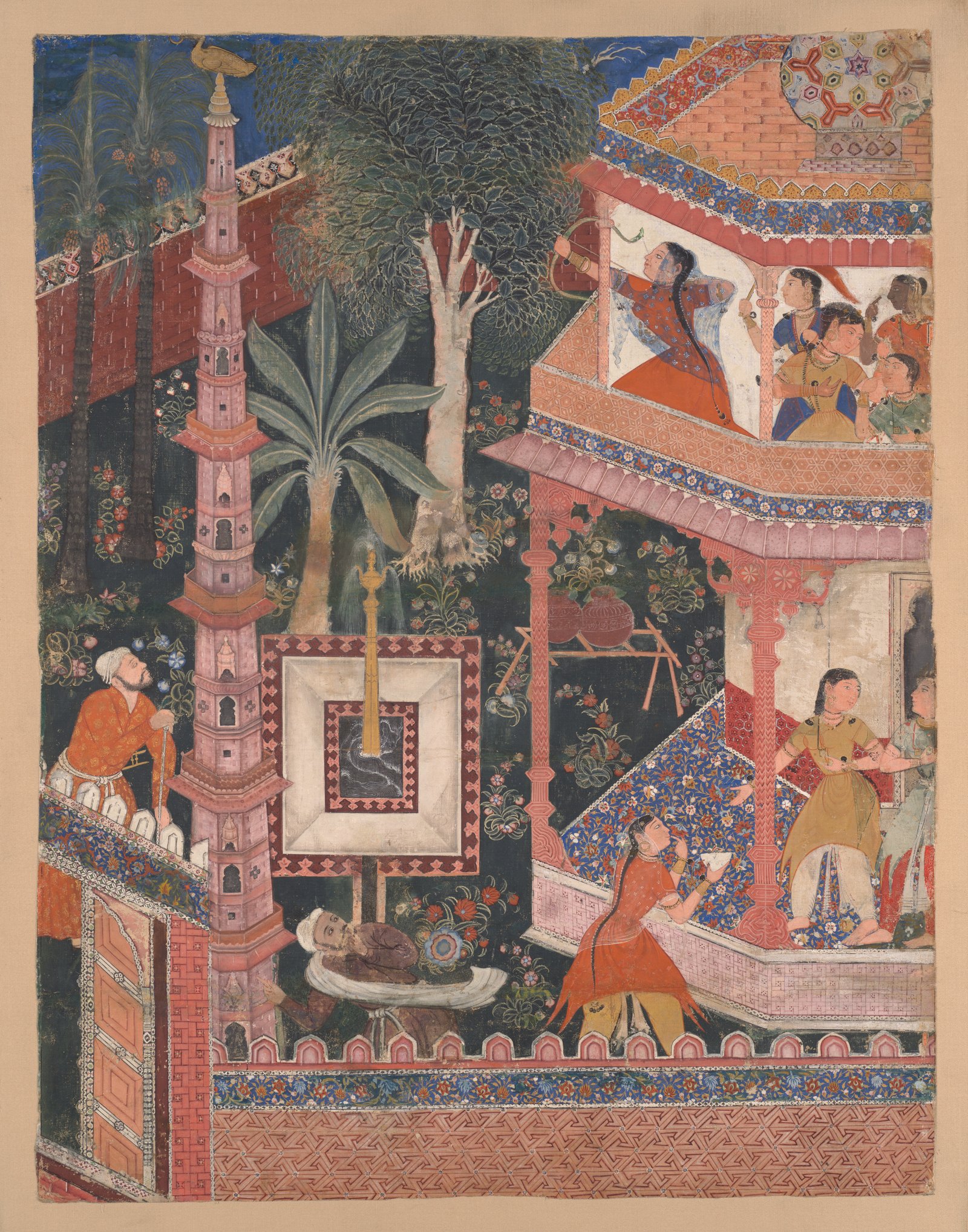

Attributed to the Kota master, “Elephants Fight” (ca. 1655-60), a finely brushed drawing with watercolor on paper, is one of Howard Hodgkin’s first finds shown in the exhibition. While, according to the artist, one of his best discoveries was the unique composition “Rawat Gokul Das at the Singh Sagar” (1806), recording a hunting excursion around a lake. He thought it was like having a piece of the Subcontinent in his home. Another highlight is the intricately painted Persian-style masterpiece “Mihrdukht Aims her Arrow at the Ring” (ca. 1570), a folio from the Hamzanama manuscript, depicting the adventures of the legendary Amir Hamza.

There are some small, exquisitely detailed pieces. The majority of the figures were conceived as illustrations for sacred books or, in any case, intended for folios to be passed from hand to hand. Yet he preferred to ‘rescue’ larger and architectural works, and he wouldn’t mind if they were damaged, as long as the original character survived. He liked to frame them and possibly hang them on the wall, unlike how they used to be displayed in museums (on cream-coloured mounts).

While the habit of collecting was probably sparked by his eccentric Irish grandmother, Florence Hodgkin, the fancy for Indian art blossomed because of his art master at Eton, Wilfred Blunt — “a dilettante collector”, as the artist described him, “rather in the tradition of my great-grandfather” (collecting run in the Hodgkins). Those were the years when Indian illustrations could be purchased cheaply in England, and that accessibility attracted to London a great connoisseur, such as the scholar and curator Stuart Cary Welch. The two were introduced to each other over lunch in a famous Polish restaurant in South Kensington in 1959 by Robert Skelton, curator at the V&A and an authority in the field. “The upshot of the meeting was that Howard’s hunting instincts were thoroughly aroused,” noted Bruce Chatwin, one of Hodgkin’s best friends.

[Here is the link to our page dedicated to Utz, the seminal novel that Bruce Chatwin wrote about art collecting, published in 1988. Ed].

Mr. Hodgkin was a man with a broad ‘general knowledge’, yet he showed little interest in conventional categories or classifications. By his own admission, his approach to collecting had nothing to do with art history. What mattered to him was how each piece looked and affected him emotionally. The same is true of the rest of his vast, eclectic collection – he collected across the board – that was sold at auction in 2017.

On that occasion, Antony Peattie, Mr. Hodgkin’s partner for the last four decades of his life, has written a text unveiling some of his routines. According to Peattie, “He marked auction catalogues with an MH for ‘must-have’ when wanted something really badly.” “If he attended in person he would hold up a pencil to signify he was continuing to bid.” And he often paid ‘too much’ for pieces that were much less than masterpieces. Nevertheless, Howard Hodgkin believed masterpieces were impossible to live with because they were too ‘demanding’. He tended to hide, lend or otherwise remove the most important works from his sight. “So he did not shy away from buying works that were easier to live with.” He had a soft spot for elephants, chairs and fragments.

After all, it was “all grist to the mill”, as the artist would say – a necessity for his own life’s work.

March 14, 2024