Venice Biennale 2015: is this the best edition of the new millennium?

- Artist collective BGL, Canada.

- Maria Papadimitriou, Greece.

- Andre Komatsu, Brazil.

- Chiaru Shiota, Japan.

- Chiaru Shiota, Japan.

- Sarah Lucas, Great Britain.

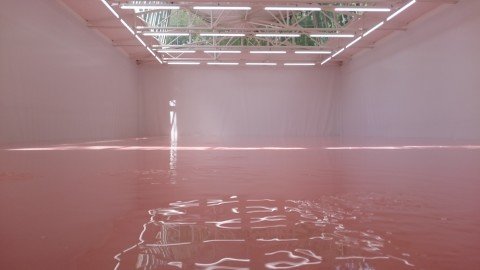

- Pamela Rosenkranz, Swiss.

- danh Vo, Denmark.

- Camille Norment, Nordic Pavilion.

- Joan Jonas, United States.

Eight hours spent visiting the national pavilions at the Giardini have convinced us that the edition 2015 of the Venice Biennale is indeed a remarkable one, possibly the best in recent years. And a first indisputable evidence of it is that finally the toilet beside the Dutch pavilion has been properly restored and kindly equipped with updated Dyson hand-dryers: costumers care is important, even for the brave and too often unkind art people.

The second important fact is that this year at the Giardini most of the pavilions are presenting charming installations and promising artists, in most of the cases surprisingly consistent with the ideological and social side of the approach to big exhibitions typical of this year International Pavilion’s curator Okwui Enwezor. Starting from Canada, for example, which is presenting a group of new works by the artist collective BGL, composed by Jasmin Bilodeau, Sébastien Giguère and Nicolas Laverdière. The useless but contorted path leading coins into the building windows is a perfect metaphor of how certain economic institutions work today: Keynesian economist Paul Krugman would definitely love it. And he would probably also love to see how clearly Maria Papadimitriou has pictured Greece’s present social identity by transferring from the Greek city of Volos to Venice a traditional animal hides and leather shop (again, “The remainder” strategy). As pointed out by the exhibition’s introductory text, this “espace trouvé” sparks series of “concerns ranging from politics and history to economics and traditions, ethics and aesthetics, fear of the foreign and the incomprehensible, and our profound anthropocentrism that allows us to define ourselves as non-wild, different from all other animals”.

To our admired Paul Krugman – whose essay “Stop the crisis now” could have been a valid alternative to Marx’s “Das Kapital” reading – we would also suggest the installation by Andre Komatsu at the Brazilian pavilion. As the Japanese-Brazilian artist told us, “it reflects on how freedom could seem such a narrow passage, while a wide cage is still a cage”.

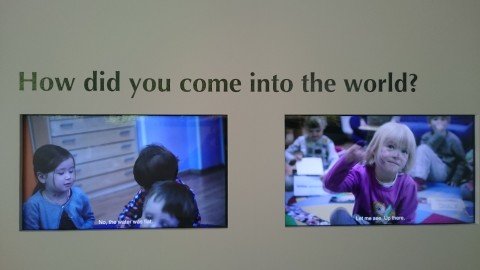

But if despite Komatsu’s warning you got trapped, you can always send someone to look for a key at the Japanese pavilion, where Chiaru Shiota’s project “The key in the hand” is located: among the 150.000 keys she has gathered together from every part of the world he will certainly find the right one (and if not, it will certainly be comforted by the cute video at the ground floor).

Nothing but perfect is the collection of works presented by Sarah Lucas at the British Pavillion: provocative, visually efficient, poetic. And similar is the Denmark pavilion, hosting an installation by Danh Vo – titled “Mothertongue” – that is only apparently cryptic. Just read the booklet and consider that religion is, after all, one of the artist’s guidelines. That is why his art practice fits always so well in Venice, and please note that both the Greek marble torso of Apollo and the chestnut wood and polychrome Christ figure in Flemish style hanging on the pavilion’s front window have been bought at auction. Short circuits.

Another enlighting parallel could be the one set between the impressive sound installation by Camille Norment (Rapture, Nordic Pavillion) and Pamela Rosenkranz’s esoteric use of colours, light, water, scent, sound, but also organic elements such as hormones and bacteria (“Our product”, Swiss pavilion). As Rosenkranz’s not accessible pink water surface – “a reminiscent of the carnate used in Renaissance painting to render the visual quality of human flesh” – plays the role of a visual support for the synthetic sound of water coming from loudspeakers, so the giant broken windows in the Nordic pavilion seem to be the physical result of the powerful music composed by the artist herself on the glass armonica, a legendary instruments creating music from glass and water to which the installation is indirectly dedicated. Here is where the metaphoric vernaculars spoken by Vo, Lucas, Komatsu, Papadimitriou, or also Joan Jonas (theatrical at the United States pavilion, with a series of clever references to Venice) make way for the pure formal approach typical of not-iconic art. Symbols.

May 5, 2015