Brussels: at Brafa 2016 seeking an art truth (the spectacles of the aggregator)

- Roman weights, 3rd cent. AD.

- Phrenology tool, Germany, 19th cent.

- Billiard scoreboard, Germany, 1930s.

- Van ReymerSwaele, money change, 16th cent.

- Scribe assis, 16th/10th cent., Egypt.

- René Magritte, Le sourire, 1960.

- Man Ray, Studies for chess pieces, 1920.

- Netherlandish tapestry, 16th century.

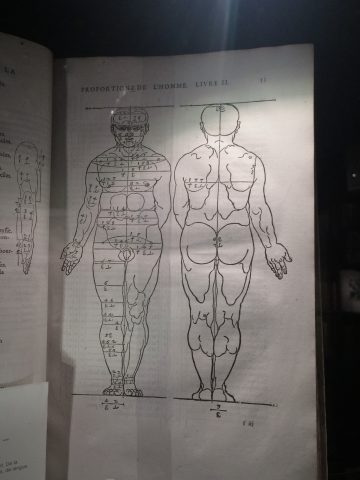

- Albrect Durer, Anatomy treatise, 16th cent.

- Alexander Calder, grand spiral en colour, 1971.

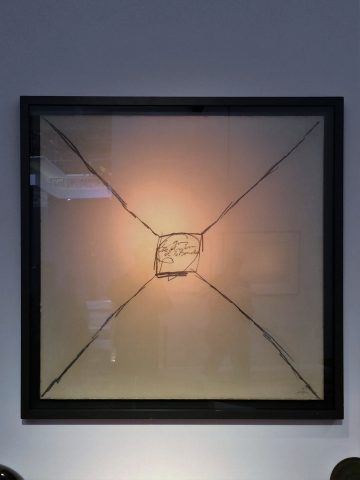

- Antoni Tàpies, The dog and the Buddha, 1973.

- Max Ernst, Mer et soleil, 1961.

We have often heard collectors comparing themselves to curators in their activity of selecting artworks. The giant political differences between these two economic and symbolic actors can however only be dismissed in order to relate their art judgement; and if we do, this activity dries up to what we could call a response to “art truths” – singularised obsessions (themes), agglomerating around specific individuals who can exercise temporary control over specific artworks. This compartmental, free-from-political-roles perspective on art judgement can be sure applied to the art critic, or to the art journalist for that matter. And yet, the act of hybridising articles with exhibitions or collections is not very often the preferred approach in writing about art fairs for example. A visit to BRAFA in Brussels turned out to be the right occasion to put on the spectacles of the aggregator, exercising some temporary control over specific artworks for the sake of a theme.

During our visit, the first object that startled our attention was also the one that gave birth to the theme after which our selection was made. This object was a weight for a scale dating back to the 3rd century AD Rome, on sale at David Ghezelbash Archéologie. Despite its shape had been distorted into a quirky agglomeration of iron and lead throughout the centuries, its function remained clear to historians: it was used to abstract and extract quantities from other objects.

Contemporary realist philosophers such as Graham Harman would say that objects withdraw from us but bits of them are graspable via metaphors and, we add, abstract quantification. After this, a division comes to mind: what if the former method is the one that leans back on to politics, human constructivism, identity and reason, whereas the latter can be seen as a trans-human activity (or production), giving a glimpse on to what stands beyond it all? We then tried to see if the free-from-politics approach mentioned in the beginning of the article could fit a trip across numbering practices present at the fair, consequently expressed either through the symbolical potential of (art) objects, what these (art) objects were literally about, or the content of these (art) objects itself.

Systems and tools for measuring connect naturally to quantifications and with no surprise these were the most evident allies backing our discourse: a phrenology device manufactured in Germany in the 19th century, an art deco billiard scoreboard (1920s), both at Le Couvent des Ursulines. Even pure figuration of these utensils counted, and a 16th century oil on wood by Marinus Van Reymerswaele titled “The Money Counter” (at Jocelyne Crouzet) appropriately showed historical ledgers and other mechanisms for mathematical aid.

Interestingly, the trip from physicality to numbering abstraction is a round one and can be objectified into recording supports. For instance, the statuette of the Assis scribe from 16th/10th century BC Egypt (at Galerie Chenel) represented what it means to hold quantifications onto long-lasting materials. In other words, abstraction coming from physicality (quantifiable goods) goes back to physicality (clay tablets) via signifier. Magritte’s “Le Sourire”, an oil on canvas from 1960 at De Jonckheere also showed this loop but with added extra layers: irony and absurdity are expressed in the impossibly far future, carved in stone in the painting-subject but seen now within a painting-physical object from a relatively close past.

Man Ray’s drawings of the analysis he carried out for the design of his own chess pieces (at Jablonka Maruani Mercier Gallery) gave some clues to what extent artists used numerical apparatuses to sustain their own practices. Following the same speculation, a Nederlandish tapestry from the 16th century at De Wit alluded to the mechanical and repetitive act of weaving, a practice that even though still not automated at the time, must have been supported by measured schemes and numbered processes – in fact, clues of such methods can be seen in preparatory cartoons. Durer’s anatomy treatise written at the beginning of the 16th century (at Sanderus Antiquariaat) was not just an example of historical humanism in this context. The schematic numeration of the human body hailed to a trans-humanist disclosure of concepts of totally external nature, as there was an entity that could speak in numbers and write them on the human body.

Our selection ended with a speculation into the difference between geometry and numbering, using three artworks made within a 10 year-long span: Alexander Calder’s “Colored Spiral” from 1971 (at Helene Bailly Gallery), Antoni Tapies’ “The Dog and The Buddha” from 1973 and Max Ernst “Sea And Sun” from 1963 (both last two at Thomas Salis Art & Design). According to the definition, geometry is the branch of mathematics concerned with space and its applicable calculations. In this move toward physicality, geometry breaks pure numerical abstraction in an all-too-human compromise: physical shapes have to become transcendental ideas. Following this theorising, what we saw in Calder’s, Tapies’ and Ernst’s paintings was a critique to geometry via an irrational geometry, or an anti-geometrical representation. These paintings didn’t explicitly refer to purity of quantities as such but they rather broke what breaks this purity of quantities. Calder did so by subtly distorting geometrical ideal shapes (the spiral), Tapies by inscribing religious anecdotal notions within shaken squares, Ernst by “geometrifying” a landscape through mundane elements (tiles) instead or rational forms.

Concluding this article, we can temporarily go back to politics and let slip the implied yet totalling quantifications residing underneath an art fair: the value of the art objects expressed in money, their transformation into assets, and capital itself. Stepping out of a specific expression of art critique, we can but admit that none of these last quantifications can be compartmentalised or reduced to temporary “art truths” and therefore they would hardly be available for a selection art game like the one that just concluded.

February 2, 2016