Judith Bernstein: Men have the organ, but they don’t own the image

Feminist pioneer Judith Bernstein points the finger at Donald Trump, but her solo show at the Drawing Center in NY is not just about him. It’s about us.

- Judith Bernstein, ph. Paul Laster.

- Judith Bernstein, Cunt Trump, 2017. Acrylic on paper, 48 x 62 inch, courtesy of the artist.

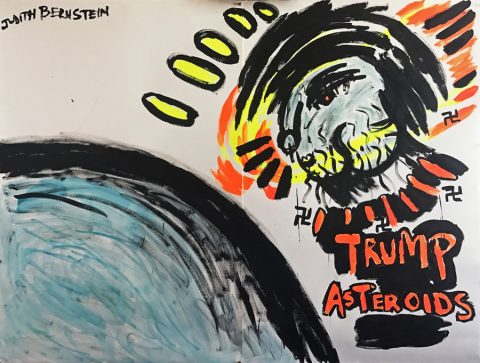

- Judith Bernstein, Trump asteroids, 2017. Acrylic and oil on paper, 49.5 x 59 inch, courtesy of the artist.

- Judith Bernstein, Trump Genie, 2016. Acrylic on paper, 29 x 41 inch, courtesy of the artist.

- Judith Bernstein, Fear, charcoal on paper, 1995, 47,5 x 63 inch, courtesy of the artist.

- Judith Bernstein, Seal of disbelief, 2017. Mixed media on paper, 96 x 96 inch, courtesy of the artist.

- Judith Bernstein, Cabinet of horrors, acrylic on paper, 41,5 x 29.5 inch, courtesy of the artist.

An expressionist painter who has been confronting conservative gender politics for more than 50 years, Judith Bernstein was a founding member of the A.I.R. Gallery — the first gallery devoted to showing female artists — and an early member of Guerilla Girls, Art Workers Coalition and Fight Censorship. Best known for her paintings and drawings of dicks, in which the phallus symbolizes both sexual freedom and male aggression, Bernstein recently turned her artistic attention to President Trump, whom she sees as the biggest and dumbest dick of all. Conceptual Fine Arts caught up with the 75-year-old artist in her loft in Chinatown, where she has lived and worked for the past five decades, to discuss her “Cabinet of Horrors” exhibition at the Drawing Center in New York.

How long have you been drawing dicks?

I started drawing dicks when I was a student at Yale in 1966. I was doing anti-war work about Vietnam and focused on the dick as a symbol of male aggression. They were anti-war, feminist and sexual all rolled into one image.

What was it that made you decide to turn screws into dicks?

It was a combination of a screw and a phallus—kind of a hybrid. It was the Pop Art period and I was thinking screw, screw, being screwed as a play on words. They took on a life of their own, becoming hairy, fetishistic and biomorphic—something that was more than mechanical.

Were you also dealing with formal issues?

It’s all a continuum going back to Mesopotamia. At Yale I read an article in the New York Times that said Edward Albee got the title of his play Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf from bathroom graffiti so I went into the men’s room and found inspiration. I’m interested in energy. I want the image to be explosive. And I also like tag lines, like cock and cunt. I’ve been using “cuntface” a lot lately, and for this specific show it’s been s”chlongface,” for Donald Trump.

What other ways have you used dicks in your work?

My work is very political. I’ve used the dick to comment on sex and war. Sex is so guttural, so much a part of life. With the dick you have the erection and ejaculation, a tremendous amount of explosion. I made a drawing in 1967 called Fun-Gun that’s an anatomical drawing of a cock with a trigger on it. It has real bullets attached to the nut sack. It was last exhibited in my 2012 New Museum survey.

Is there a psychological aspect to your use of dicks?

Absolutely, there’s always a psychological aspect to it. When I make drawings that are 9 by 30 feet it’s like mine’s bigger than yours. Men have the organ, but they don’t own the image. I can do whatever I want with it. I can make it as large as I want. It infantilizes men when they see it because the scale is so enormous. It’s become a metaphor for so many issues, not only sex and war.

Did you ever get into any disputes with fellow feminists about dealing with this kind of male subject, which could almost be interpreted as worship?

Sometimes people are not quite sure to make of my dicks, especially when they see the aggrandizement. I’m making a comment, but I’m also buying into it. As a result, I’ve been left out of a lot of feminist exhibitions, for example Wack!, which was at MOCA LA and MoMA PS1 in 2007. I was left out of that show because a number of people felt that dick art is not feminist. But I’m actually observing the guys, making a social comment and taking on that image.

Pardon the pun, but did the dicks lead to the cunts, your “cuntface” paintings and drawings?

Yes, I had been doing these dick paintings and drawings for a while and I wanted to actually get into some “feminist” imagery. I had always been observing women, too. Art history represents vaginas that have been romanticized. I don’t feel that way at all. My mother was an angry woman. She didn’t like her life. I was also part of a lot of feminist groups, for example Fight Censorship with Louise Bourgeois, Anita Steckel and Joan Semmel, and the Guerilla Girls. The women in these groups felt that they were entitled to be part of the art world—which they were entitled to be—but they didn’t get it. They wanted access to the system. I saw a lot of that rage and anger and I have a lot of rage and anger, too. I don’t leave myself out of the critique, but I want to keep it in the drawings and paintings. I’m not angry in general. I lot of people have this amorphous anger that goes all over. I don’t have that at all. I’m sympathetic to men. Women have it harder, but I’m still sympathetic to men.

In a previous interview you said that you used “Big Bang–style explosive strokes” in these paintings. I like that description. Where did it originate?

I made the analogy between the big bang, the birth of the universe and women. It’s interesting to make that connection. There’s so much more interest in the universe nowadays. When I was a kid there was just Captain Video and his Video Rangers, a TV show where there were three planets. We obviously had 11 or something like that, but nevertheless we didn’t have the information that we have now about planets, about life. It’s really mind-blowing. I use big bang and explosiveness for women in terms of anger and birth and their importance, by putting them at the center of it all.

Art historically, are you also riffing on Courbet’s controversial painting The Origin of the World?

Yes, but I want it to be more than a romanticized view of women, or men for that fact, or whatever. Sexuality is now on a continuum. It’s much more complex, much more interesting and much more nuanced that it ever was. Before it was gay or straight or maybe bi, but now it’s much more complicated and much more interesting.

When did you start making words works and why?

I had used words to name pieces, but then I started making these charcoal word works in the mid-‘80s. I love charcoal. It’s my favorite medium. I like the way that rich, rich charcoal looks. I like the sensuality of it; I like the nuance of it; and I literally like hands-on nature of it. I like getting filthy. One of the first pieces was a big wall mural of my name. Then I began using words that were psychological at the time, like White Rage and Black Holes. In this specific show I have Equality, Evil, Fear, Justice and Liberty, which are very poignant things.

What’s the idea behind your “cockman” and “cockhead” works?

I first made my cockman image in 1966. It was the piece Cockman Shall Rise Again, which was about George Wallace, a very reactionary governor from Alabama. I made it again in 2015 as Cockman Always Rises, which referenced Donald Trump. The issue, however, is bigger than Donald Trump. The Drawing Center show is centered on Donald Trump, but it’s not just about him. It’s about the times we live in and the society that actually created this guy. It’s really terrifying. It’s like Nazism when Hitler came to power.

What is it about Trump that makes him a good candidate for your “cockman” works?

Oh my god — if you want the truth of it — I couldn’t get a better candidate. He’s a fool. He’s a monster. He’s a jester. He’s a sexist. And he’s a racist. He’s also a con man, who’s using the White House for his own cash machine. He’s the perfect subject for cockman. He just fell in my lap, so to say. I use the term cockman in a very negative way, because sometime people can think of that as being something positive. There’s nothing positive about this man. If there is a positive, it’s that he’s better than Hitler so far, but that’s not saying much.

What’s the title of your show, “Cabinet of Horrors”, represent?

I see all of the people in the U.S. Cabinet as clones of Trump. He picked people like himself. He picked people to destroy the areas that they were supposed to protect. I see it as a Cabinet of Horrors, and Trump as the biggest horror of all. One of the drawings is titled Frankenschlong, which shows Trump as a Frankenstein-like monster and I put him on a three-dollar bill because he’s a fake.

Is this work meant to be satirical or a dead-on affront?

It’s a dead-on affront. In the past I didn’t always target a person. I did do a piece in 1967 on LBJ, which the Whitney Museum also owns, and I was thinking of the ditty, “Hey! Hey! LBJ! How many kids did you kill today?” when I made it. I also did a piece in 1969 on Nixon, First National Dick, but very rarely have I targeted individuals. Trump is the dumbest dick of all. He’s so dumb he doesn’t even know how dumb he is. It’s all about him. He couldn’t care less about anything else. It’s his Trump universe. He’s been elected by television culture. His background is Miss Universe and “You’re fired.”

Besides the comparison of Trump to Hitler and Nazis you also deal with him in some feminist ways in the pieces All-American Spread Eagle and Money Shot.

I use a lot of American symbols because he’s screwing around and cumming all over them—the flag, the White House, the Capital, the presidential seal, the dollar bill—anything that’s important to us. One of the Money Shot pieces is Trump with Kim Jong-Un and in another he’s facing off Putin. They’re fantasies about guys getting together to see who has the longest dick and end up shooting each other in the face. And then there are ones with the Treasury as a slot machine and the Capital as the jackpot. But I do feminize Trump in All-American Spread Eagle, which shows the Seal of the President of the United States in the crotch of a woman. Trump always has to be more macho than everyone else, which is such a ruse. When people are that macho they’re hiding something. It’s really about fear, the fear of the father. The one that I did with Kim Jong-Un I named World War III, but I hope to god that there’s no connection.

November 7, 2017