The “Free Work” of Karel Martens

Acclaimed graphic designer Karel Martens has made artwork for decades. We delve into this artistic production and its relation with freedom and opportunity.

Disclaimer: the following article is about Karel Martens the artist, not about Karel Martens the graphic designer. Of course, both characters are embodied in the same person, yet they can be separated thanks to his so-called “free work,” and especially his monoprints. Popular for the design of the books of the socialist SUN publishing house in 1970’s Netherlands, as well as for the architecture journal OASE, Martens the artist has actually been as active as any other of his facets, steadily producing “free work.”

Writer and artist at the artist studio. June 2019.

Free Work?

Why do we write free work in quotation marks, one might ask. Perhaps pedantically, this is to raise the nonetheless important question of whether his artistic work is and should be considered free, or at least freer than his graphic design. Nick Currie writes that Martens makes work on commission for clients; this is the design work, then there is the work he makes for his own pleasure; that is his free work. Indeed, free in this argument means free from any authority to answer to, a commissioner. Here comes the pleasure of it that Currie mentions. This is the situation of a person unbound by the last word from an institution which can and is likely to override decisions. But to what extent is Martens’ art free even though it doesn’t have to deal with these constraints? The point here is not to deny that Martens’ monoprints stem from the kind of liberty and the pleasure typical of activities happening beyond a contract, i.e. beyond the typical economic relation of client and supplier. That liberty of the monoprints is undeniable. We rather want to point to the issue of artistic freedom through Martens’ artwork, shedding some light on different games of control, or lack thereof, that are played within those colour compositions built up on found paper that are his monoprints.

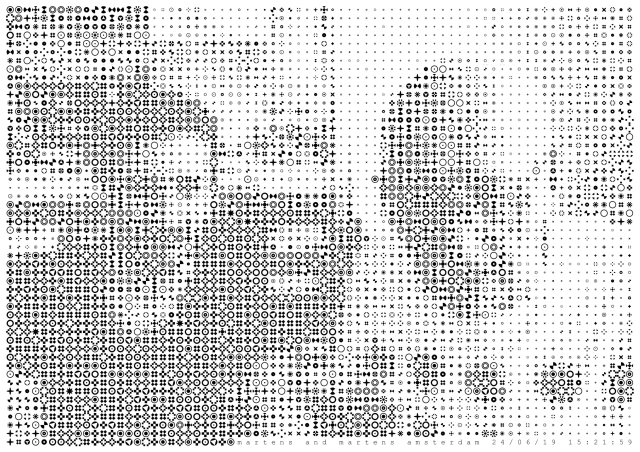

Karel Martens, monoprints, 2017-18. Courtesy of Wilfried Lentz Rotterdam.

A Cleverly Taken Opportunity

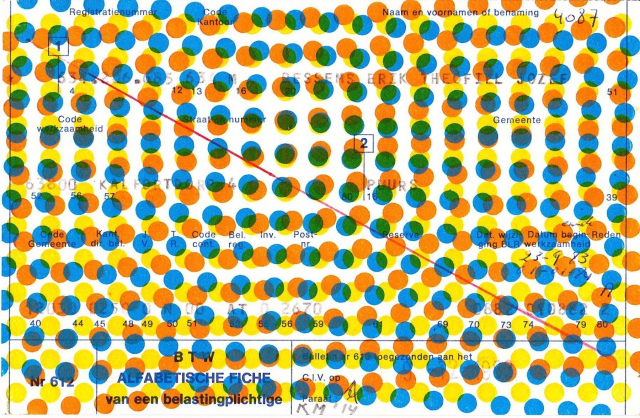

One way to approach the question of artistic liberty is through the idea of access to physical materials, in the sense that what is at hand is what dictates a specific artistic output. Imagine how fantastic and terrifying it would be for an artist to have access to a catalogue of all things, a list of all possible materials from which to pick the ideal ingredient for his or her oeuvre. Fortunately or not, this kind of freedom doesn’t exist and Martens’ monoprints attest to that fact. These works are built on found surfaces like index cards or newspapers. They are archival, everyday objects that do not receive a specific attention and are overlooked. This material support arrived instead of being sought out, as did the metal pieces used as printing plates to compose those colour arrangements in the monoprints. Mind you, this argument is not meant to deprive the artist of the praise rightfully deserved for the creation of his work. Rather, the argument is meant to show that artistic work is bound to specific moments of opportunity–to show that the actual act of artistic creation is somewhat distant from the image of freedom enjoyed by the stereotypical romantic painter who channels genius choices onto the blank canvas.

Artistic Efficiency

As Robin Kinross writes, the merit of Martens’ graphic design comes from the special skill of achieving a lot with very little. Similarly, his “free work” points to a kind of artistic efficiency: from limited input like wasted index cards, metal plates from a junkyard, and an old press, come large outputs as formally powerful artworks whose aesthetic beauty is hard to deny. Skilfully taken opportunities rather than freedom characterise Martens’ monoprints. In an age where economising resources has become an ethical obligation, being talented at recycling found materials can be seen as a sufficient reason for praise. Even for the relatively small scale of an artwork, the attitude of making do with what is available should be seen as absolutely relevant.

Karel Martens, Monoprint on Newspaper (detail), 1992. Courtesy of Wilfried Lentz Rotterdam.

Spolia and Art

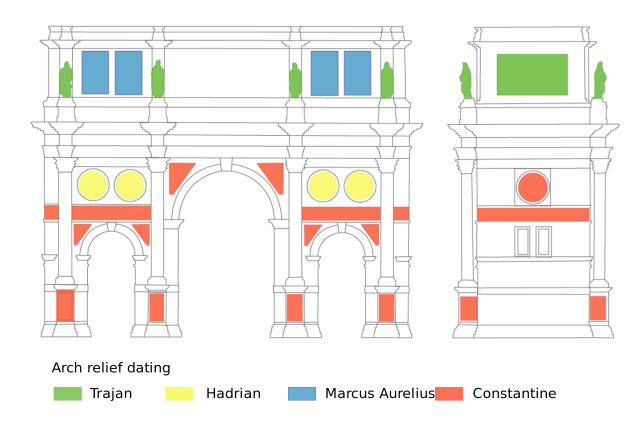

Let’s take the architecture term spolia, which refers to the reuse of found constructions elements to make new buildings. A primary example is the Arch of Constantine in Rome, which embeds decorations and materials from at least four different epochs; or, in this regards, we could mention the Romanesque architecture (here is the link to our feature about Romanesque architecture in Como and it’s surroundings). Theorists mention two main reasons for architects to use spolia. The first is convenience: found material might be cheaper and easier to use. For example, why would one quarry new marble when some is available from a demolished building nearby? The second is symbolism: found material, especially ornaments, can be included in buildings to send specific messages. For example, emperors would show off their conquests by embedding pieces of subjugated people’s buildings incorporated into their own.

Spolia on Constantine Arch. Source: Wikipedia.

We would like to propose a third reason for spolia, this time not necessarily linked to architecture. It is the idea present in Martens’ monoprints, i.e., a certain game of opportunity, a certain attitude of cleverly twisting what comes by chance for the purpose of creating value in the form of striking artworks. Irénée Scalbert calls this attitude bricoleur, a figure that “is always waist-deep in practical situations, nowhere more comfortable than between the sensible and the intelligible, between the earthly and the aerial.” It is the important figure of the efficient artist—those who do much with little—opposing to the free artists. In the end, considering Marten’s monoprints as his “free work” is indeed justified, yet in doing so, prevailing attitudes may leave out a crucial aspect—the relevance of his artwork comes from its finely exploited unfreedom.

Karel Martens, monoprint, 2014. Courtesy of Wilfried Lentz Rotterdam.

—

Karel Martens has had solo presentations of his artwork at Kunstverein München, Platform-L Contemporary Art Centre in Seoul, P! New York, the Design Museum in Ghent, and Wilfried Lentz Rotterdam. Roma Publications, one of the best publishers of artist books in Europe (here included in our selection), has recently release a reprint of Marten’s famous monograph, and it has published catalogues of his monoprints. Studio Team Thursday will present an exhibition of Karel Martens’ artwork opening on September 26th in Rotterdam.

December 18, 2019