Kengné Téguia’s concentric circles

Kengné Téguia’s artworks are objects that call forth to grasp the artist’s own questions, as well the meanings in their appearance and sound.

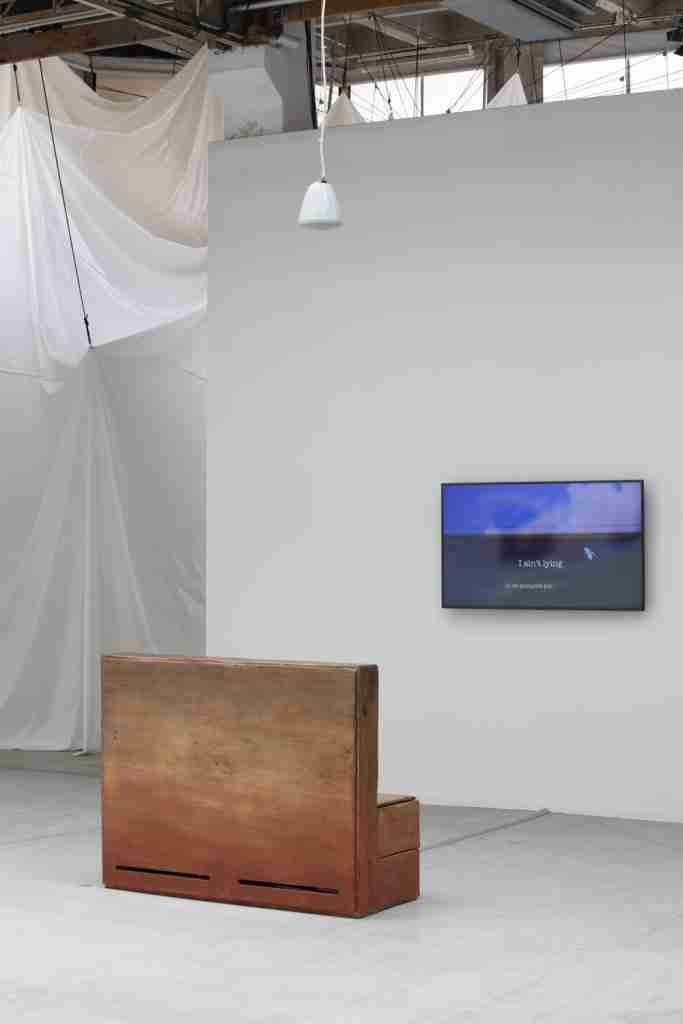

There are things that explode without destroying anything and the sculptural benches by French Paris-based artist Kengné Téguia are one of those things. They are not really these odd devices of course, but physical parts of an art installation in a specific exhibition—a large group show at Palais de Tokyo in Paris that took place a few months ago. They are explosive metaphorical objects.

To some extent, everything is allegorical. Everything can prompt thoughts and create meanings that are not evident at first sight, like allegories do. Think of a boring IKEA chair, which still refers to the story of its production, to its travel in a trailer truck, to the sea freight container in which it stood quiet, to the machine that cut its wood, and more. Yet, some objects just explode with tales when we start messing with them and we often refer to these loaded objects as artworks. Perhaps, the greater the explosion, the better artworks they are. Kengné Téguia’s sculptural benches explode a great deal.

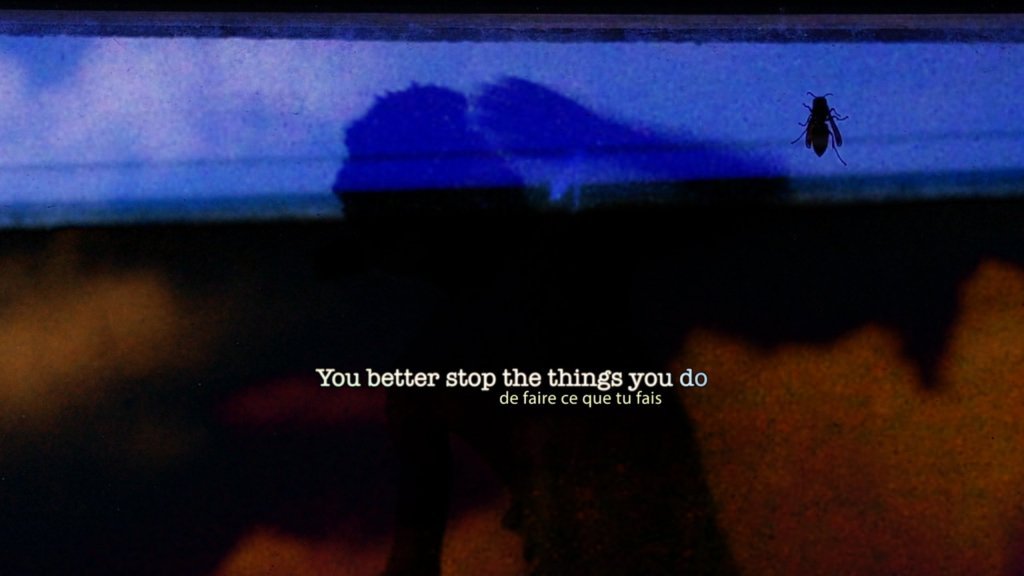

Another way to look at this work is to image concentric circles, whose centre hosts the elements of an art installation, the benches for example. Zooming out, one starts to perceive the external circles, seeing and hearing more. The benches are also containers for sound speakers, vibrating with the sound coming out of them. The first outer circle one encounters is the larger project, a larger design, a sound installation. There appears the electric cable running out of the benches, reaching the wall in front, where screens show video work. The larger circle comprises Kengné Téguia’s moving images too.

From bench to installation, these are but the physical circles of the concentric arrangement of Kengné Téguia, the literally tangible qualia of it. Yet, there is more to come. For example, the benches are of a mysterious design: they are made of simple industrial wood, uncannily smoothed out by the artist following a precise aesthetic plan. Their tint is exceptional, meaningful. It is our starting point in grasping the circles beyond what, in the installation, only meets the ear, the hand, the eye.

In her essay about Andres Serrano, Lucy Lippard writes that artworks can be engendered by the personal concerns of the artist. As obvious as this might sound, there is a difference between art that does without its author and art that doesn’t. Kengné Téguia lays squarely in the latter category and even a simple choice of colour for his sculptures cannot be understood without understanding him. A check on the artist’s social media reveals where choices come from. The earthly reddish of his benches unravels meanings in respect to the artist’s identity and life, which are necessary aspects of his art. The concentric circles expand to himself. A visit to Kengné Téguia’s studio in Paris is the pretext to collect quotes from him:

Being black makes you articulate as a deaf one, which means that I have no choice but to work hard to speak correctly. As a deaf person, relationship with speech is complicated, and the fact that my deafness becomes invisible, at least when I speak, tells a lot about my position as a black too, which remains the only visible variable.

We learn how his choice of pigment reveals an intention to express a link to Cameroon, how the red earth of the country is transformed into tint for the sculptural furniture of an installation at Palais de Tokyo. We are far from essentialism though, as the artist provides no statement of what defines a certain identity, let alone his. There is no post-colonial activism per se either. The layers in his persona are too many to be squeezed in an identifiable bunch, not to mention his own very personal intuitions as a designer and artist, which are too critical for an essentialist reduction. His work blurs the line between individual and cultural concerns to say the least.

At his studio, he continues: “I belong to a minority within a minority within a minority, a deaf, HIV+, gay, black artist. This is what I actually am and it is important that my work gives a feeling that something is going on there.” The concentric layers expand beyond the physical, the retinal and aural, as the personal concerns of the artist are both fundamental to understanding his art and cannot be fully grasped by only hearing his sound pieces, looking at his videos and performances or sitting on his sculptural benches.

In a way or another, all artistic mediums are exclusive. They prevent certain people from participating in the experience they are supposed to deliver. Think of what painting is for the blind, theatre is for those who cannot afford tickets, etc. The topic of medium exclusivity is one of the political circles expanding from Kengné Téguia’s installation. He tells us:

When I work with technicians, I understand they tune the speakers according to the standards of hearing people, which are not accessible to me. In this context, I have to impose myself to be heard, to make my reality be crucial in my work and for those who see it and hear it.

Regardless of the criticality of discriminatory mediums, reducing Kengné Téguia’s work to this issue would not only miss all the other layers (the concentric circles) we have mentioned so far, but would also dangerously hint at some kind of self-obsession that is simply not present. Even the more political meanings remain truly artistic in his practice, as they are never explicitly told. There is no straightforward activism against exclusion in his installation, but rather an expression of how art can be made from the specific assemblage of worries and needs of the artist.

Eventually we return to our first contact with Kengné Téguia, that is the coming into being of a bench in the mind of a visitor to an exhibition, a physical object–a sculpture perhaps–that explodes and expands to include pigments, cables, screens, sounds, images, and meanings, eventually stopping and starting again at the specificity of the artist, his own dispositions and making. This is true critical work.

July 19, 2021