The figure of the rope between gore, eros and faith

Goya, Lady Gaga, Man Ray, Giulio Paolini, Georg Baselitz, Jake and Dinos Chapman, Antonello & co., all tied together to a vibrating rope.

Sursum corda! Lift up your hearts! The Latin term corda (rope) derives from the noun cor cordis, the heart. But what does rope have to do with the heart? The lively heart and the rough rope seem rather opposite elements. The former suggests affection and feelings. Shoes, sausages, curtains and violins come to mind with the latter. Yet the link between the two exists, and it has to do with the idea of vibration and thrill. Etymologically, the rope and the heart derive from the Indo-European kerd, which refers to some kind of vibration. Latin verbs like correre (to run) have the same root.

Hearts of Rope Hating Men

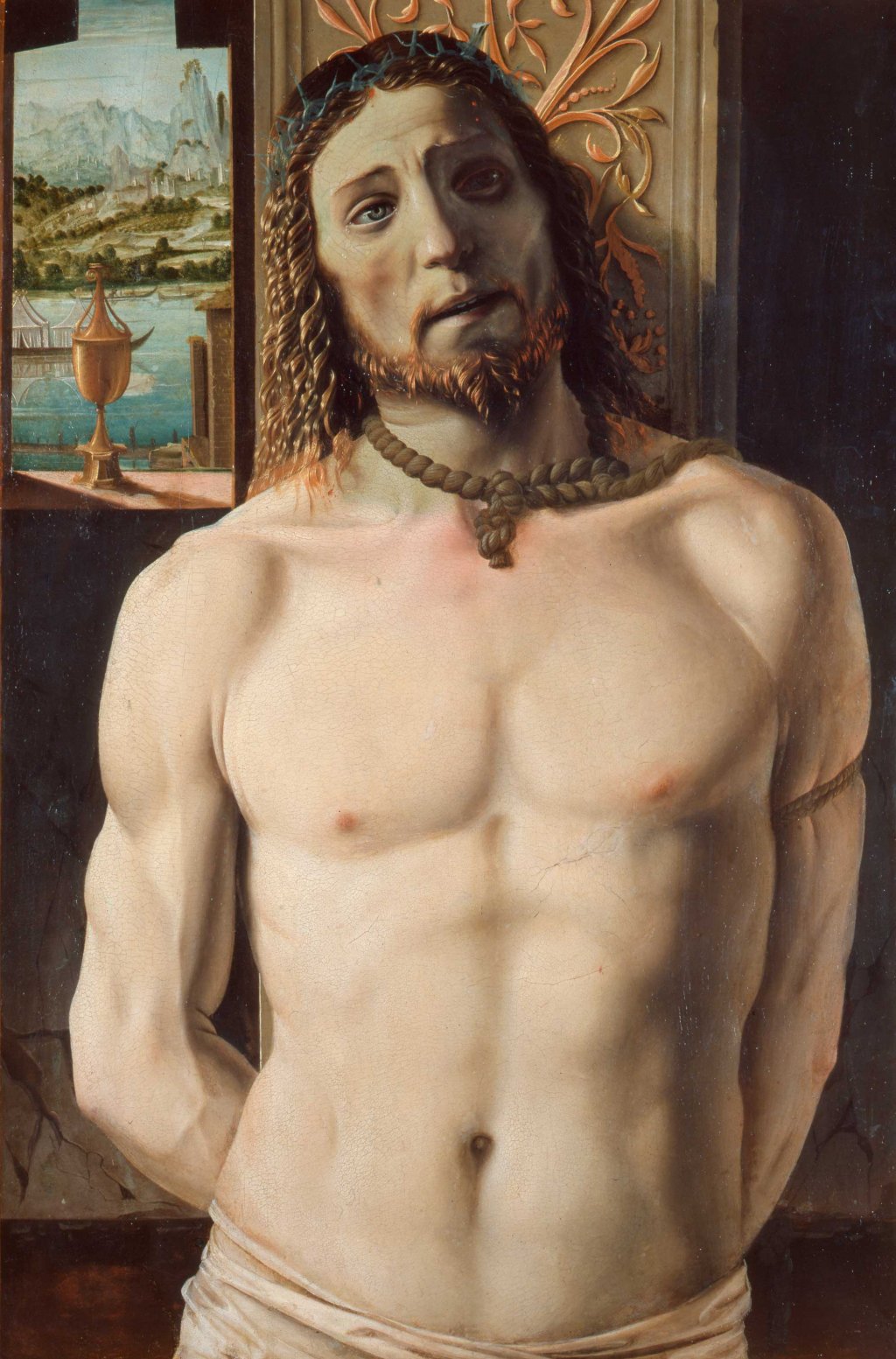

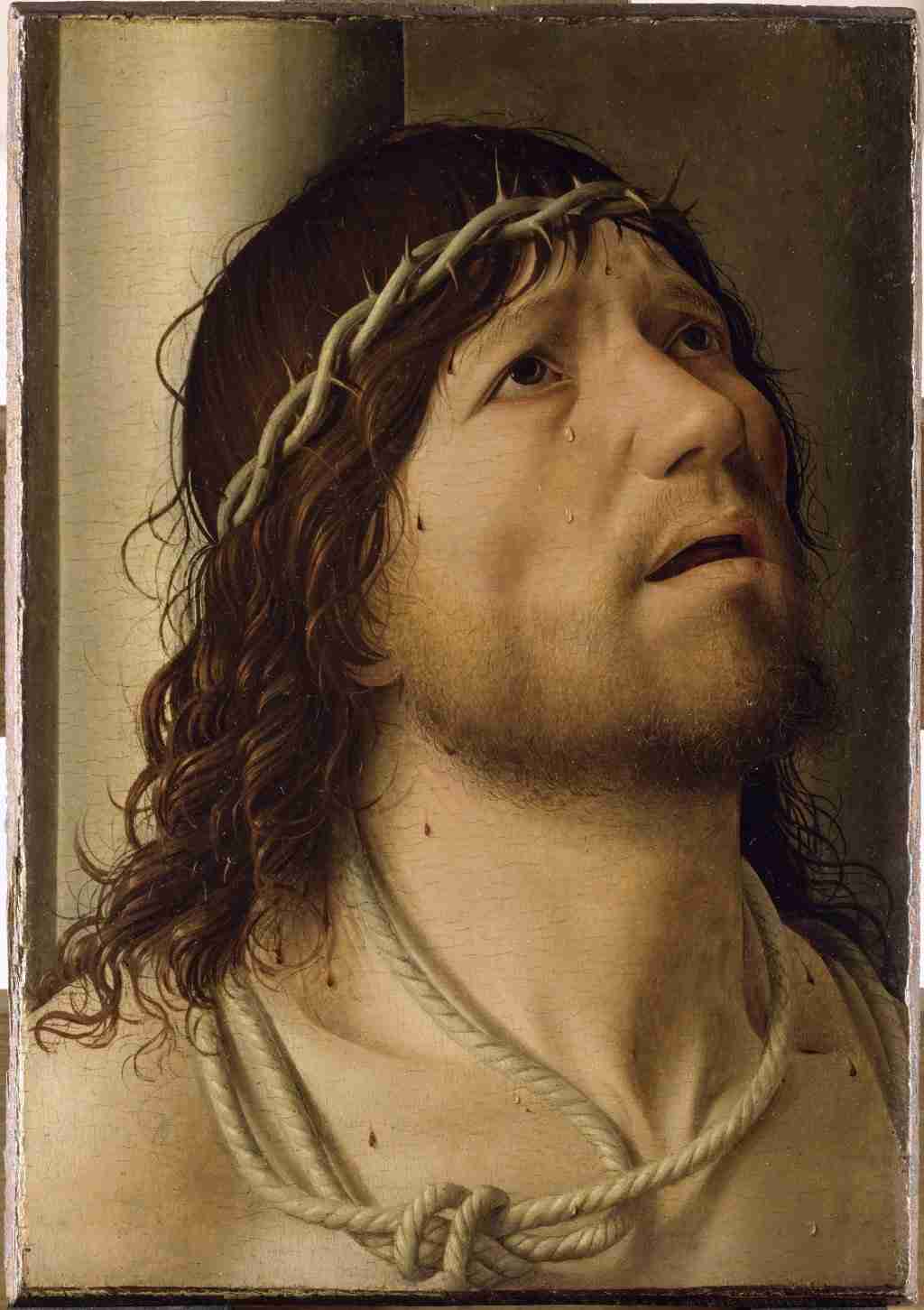

Let’s start with the knotted rope in Georges de La Tour’s Saint Jerome at Prayer. The painter is not afraid of showing wrinkles or swipes of blood in the extraordinary depiction of a soul that purifies itself with a rope. We are in the theatre of cruelty. But how many martyrs have been depicted over the centuries: it only takes a few examples to see how the rope is the undisturbed creator of torment and death. Take the emblematic case of Christ at the Column by both Bramante and Antonello.

[Here is our piece on hidden symbols in the work of Antonello’s work. Ed.]

The Holy Rope of the Hanged Man

Until his death Eduard Manet kept in his studio the portrait of a blond boy with juicy lips, laughing eyes, an irreverent look, standing in front of a big basket of cherries. He painted the picture in 1859. It is titled The Boy with Cherries and is now in the collection of the Gulbenkian Foundation in Lisbon. Everything in the work is red, from the boy’s fez to the fruits. All this light, this vivid pleasure of life that gushes out is dramatically tinged with death “by rope” in the end. The tragic story of Alexander, this being the name of Manet’s model, is described by Baudelaire in an almost singing, dreamlike prose-poem entitled The Rope, included in the collection The Spleen of Paris from the end of the 1860s.

In the remote part of the city where I live, where vast green spaces still separate the buildings, I often observed a child whose fierce and mischievous physiognomy appealed to me right away, more than any other. He posed for me more than once, and I transformed him into a little bohemian, or an angel, or Cupid. I made him carry a vagabond’s violin, the crown of thorns and the nails of the passion, and Eros’s torch.

In the story, the boy’s poor parents sell him to a painter. The boy will soon fall into alcoholism. His master leaves him alone in the studio for a few days and upon his return he finds him tied with a thin rope, lifted above the ground like a shapeless, disjointed puppet, hanging from a nail on the door of a wardrobe.

The little monster had used a very thin cord that had entered deeply into his flesh, and it was now necessary, with fine-bladed scissors, to dig it out from between the two swollen rolls of flesh to free his neck.

No tear comes from the boy’s parents. They think he still enjoyed glimpses of life. Yet the mother, finally in grief, asks the artist to show her the place where the boy took his life.

Her despair had, no doubt, so distressed her that she was now overcome with tenderness for the instrument of her son’s death, and wanted to keep it as a horrible and cherished relic. And she grabbed the nail and the rope. […] But the next day I received a packet of letters: some from the tenants of my house, some from the neighboring houses; one from the first floor; another from the second; another from the third, and so on, some in a half-joking style, as though seeking to disguise the sincerity of their request beneath an obvious jest; others crudely shameless and misspelled, but all grasping at the same goal: to obtain from me a piece of the bleak and beatific rope.

The Hanging

According to the frightening dogmas of faith defended by the Inquisitors to combat the Protestant reformation in the 16th century, there is a compromise between soul and body. These courts would use a specific instrument of confession of the concealed “sins:” the so-called “piece of rope,” which was not considered torture as no blood was spilled during its use.

There is a taste for gore in the work of Alessandro Magnasco (1667-1749), an expert on torments and prison scenes. His paintings are dark, made of dense and material brushstrokes where sombre colours prevail. There is neither pity nor piety in his scenes of interrogations and martyrs, for example in Interrogations in Jail painted between 1710 and 1720, now at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna.

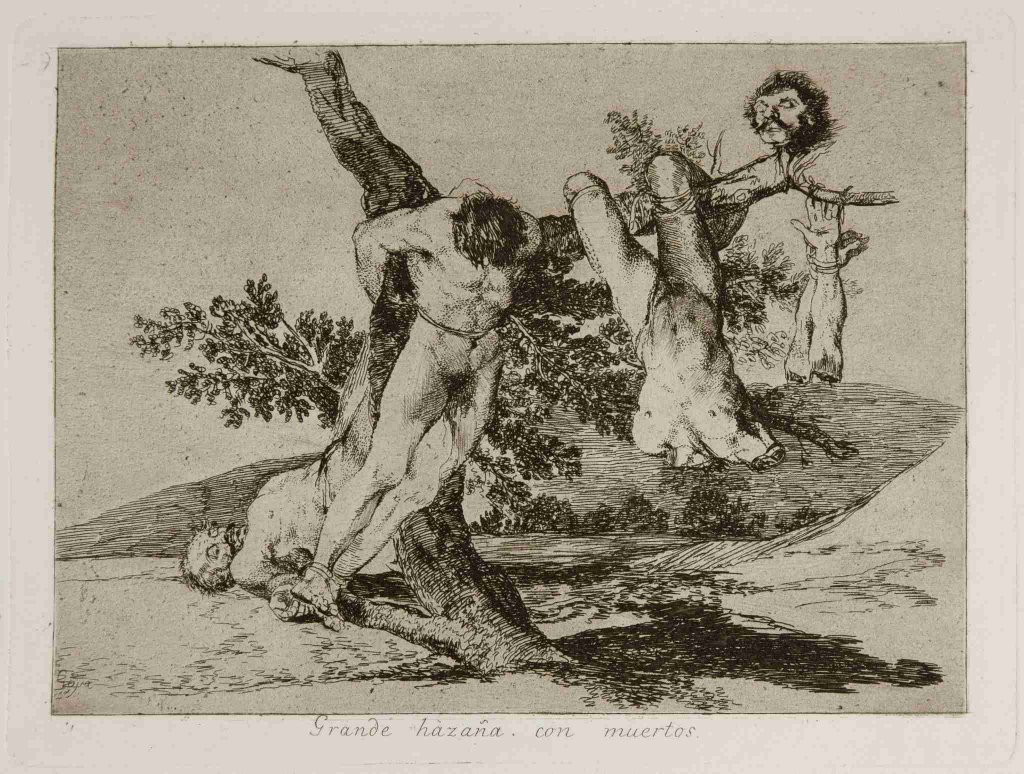

Writes Susan Sontag in her Regarding the Pain of Others: “Most depictions of tormented, mutilated bodies do arouse a prurient interest. The Disasters of War is notably an exception: Goya’s images cannot be looked at in a spirit of prurience. They don’t dwell on the beauty of the human body; bodies are heavy, and thickly clothed.” The plate 39 entitled Grande hazaña! Con muertos! is exemplary, and so is the number 36 entitled Tampoco, where the Napoleonic hussar, like the inquisitors of Magnasco, observes with an imperturbably satisfied expression a body hanging from a rope.

The Chapman brothers’ Great Deeds Against the Dead (1994) is the three-dimensional version of Goya’s engraving Grande hazaña! Con muertos!. The sculpture is a life-size work showing emasculated bodies, one of which is torn to pieces and hung with ropes on a tree. The shock is greater than Goya’s engraving: the eyes can’t look, yet they are drawn back to it with curiosity, desire for horror and sadism.

In the Chapman brothers’ work, Goya’s filter in the face of horror fades off. The painter followed his Christian morality in showing the brutality of war. In his Disasters of War there is a religious overtone in the reference to the figure of Christ abandoned on the cross, offering his own corpse as a gesture of love towards humans. In the sculpture, it is voyeurism that predominates instead, a passion for atrocity, a gaze in between pleasure and pain.

Jake e Dinos Chapman, “Great Deeds Against the Dead”, 1994 mannequin and mixed media – Photo: courtesy of the artists

Jake e Dinos Chapman, “Great Deeds Against the Dead”, 1994 mannequin and mixed media – Photo: courtesy of the artists

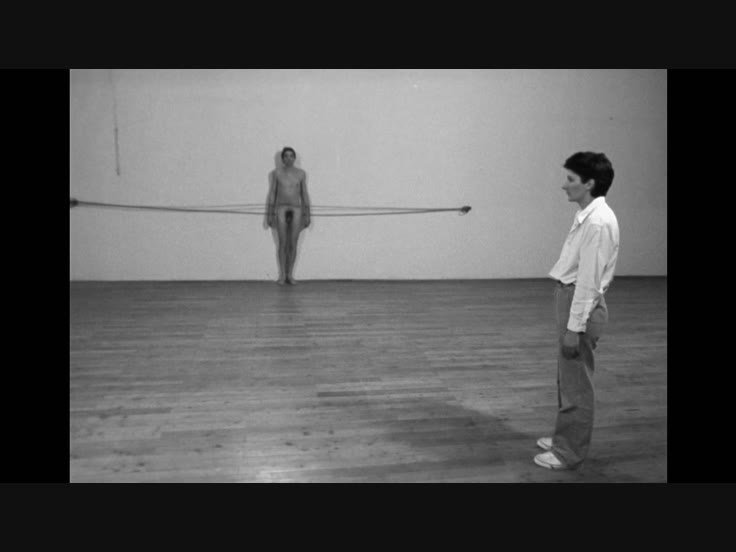

Rope Sacrifice in Body Art

Artists have played the role of scapegoats at times, for example in April 1978 at H-Humanic Gallery in Graz. Completely naked, Ulay (Abramović’s companion back then) shows up tied to an elastic band fixed to the wall. The performance consists of his desperate runs towards the centre of the gallery, made useless by the rope pulling him back with force. He obsessively starts over again, trying to free himself. He always fails. Meanwhile Marina Abramović is standing by, fully dressed, silent, totally indifferent to Ulay’s efforts like the judges of Magnasco or the hussar of Goya’s engraving. The contrast between the two could not be greater.

Ulay’s pain is clear. His body violently hits the wall every time he bounces back. Abramović does nothing about it, simply watching his partner’s effort in an aseptic and indifferent way. Suddenly a man comes out of the audience and attacks Abramović. This third character is part of the performance, but the audience doesn’t know it. The spectators take a psychologically ambiguous role: on the one hand, the attacker seems to be part of them, but nobody wants to identify with him, or join him. On the other hand, after 42 minutes of desperate running and increasingly tragic rebounds against the wall, Ulay has become a scapegoat. Marina Abramović, who attracts feelings of hatred from the audience for her indifference does not rebel and finally succumbs under the attack of the fake spectator. The public is puzzled: who is guilty?

In his The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, says Vasari about Andrea del Castagno: “he pleased the whole city and particularly the connoisseurs of painting, so much so that he was no longer called Andrea del Castagno but Andrea degl’Impiccati (Andrea of the Hanging).” Vasari refers to a specific job of Andrea. Following the failed coup d’état in Florence by the Pazzi’s family in 1478, where Giuliano de’ Medici was killed in Santa Maria del Fiore and the future ruler Lorenzo Il Magnifico was wounded, the state decided that all those involved in the conspiracy were to be painted as traitors on the facade of the Palazzo del Podestà, but not before they were hanged and their bodies thrown onto the square. Andrea del Castagno was given the commission to paint these “infamous portraits.” Legend has it that this episode gave a second name (the traitor) to the tarot card of the hanged man, where the upside body with a leg bent 90 degrees might derive from pictures by del Castagno or Andrea del Sarto, who painted a similar image in his Ritratto d’Infamia from 1528-30.

Another artist has built his reputation through a similar motif, producing works in which the subjects are represented upside down, like a symbolic vision of an inverted world. It is the German Georg Baselitz, who began this series in the 1960s with disorienting and tragic creativity.

In recent years Baselitz has created giant upside-down self-portraits, where he shows himself naked, emphasising the signs of age, real and symbolic scars of his experiences: spots, veins, wrinkles and scars are collected in an extraterrestrial body, almost a shapeless and milky mass whose borders are blurred, torn by the expressionist power of the dissolving paint.

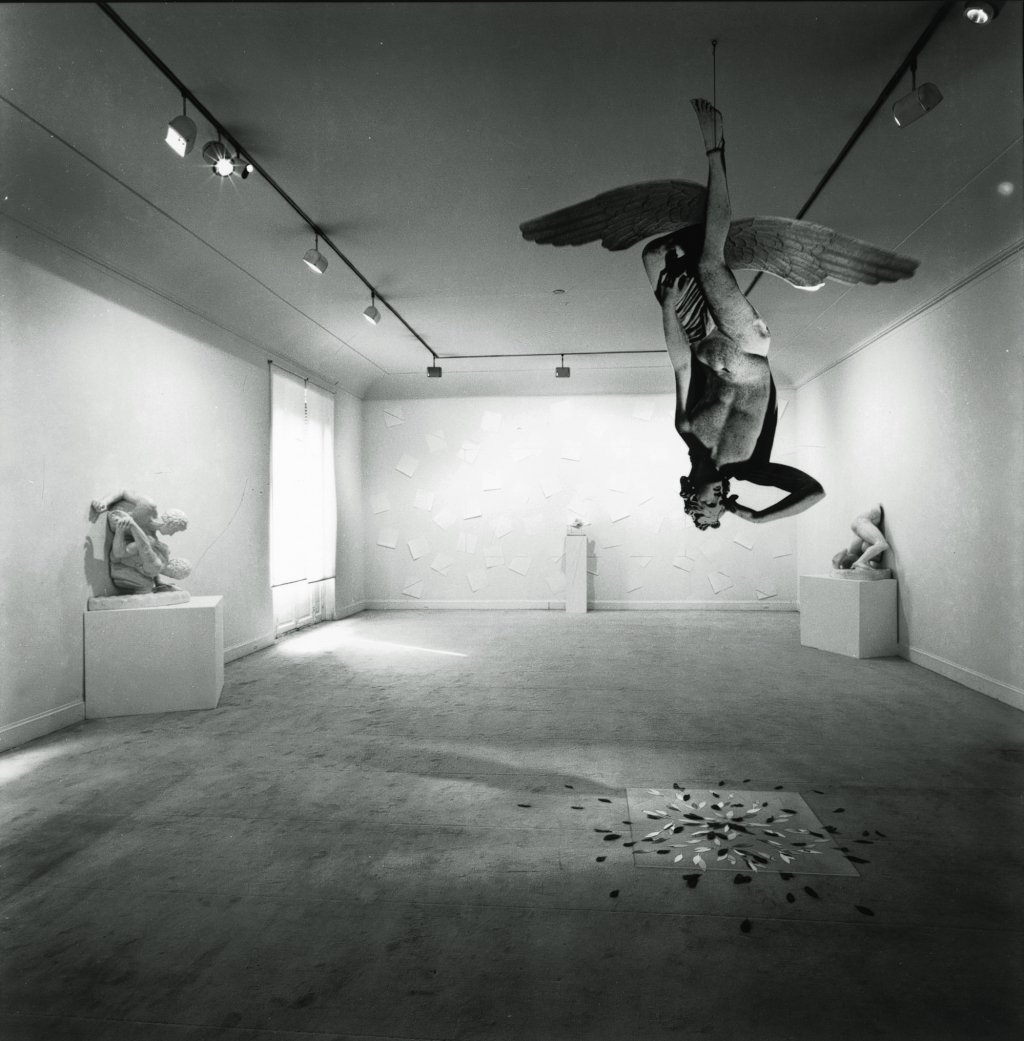

When memories begin to fade and reality mocks myths, there comes the free fall of Giulio Paolini’s idols. Aria is the title of one of his works from the 1980s, where an involute Icarus is tied with one foot, hanging over a shattered sheet of glass. This creature too, like those condemned to Magnasco’s rope seems to have suffered one of those free falls to the ground, shattering the glass into a thousand pieces.

This upside down angel is built with a photographic collage of works by the most neoclassical of the Italian artists: Canova. It is enclosed between two sheets of plexiglas. Icarus precipitating towards a flat glass abyss is a sort of hybrid born from the union of the body of the Genio funebre, a sculpture by Canova on the Sepulchre of Clement XIII (1787-92), accompanied by arbitrary wings, which are copies of a wing from the other Genio funebre on the Stuart’s Cenotaph (1817-19).

Paolini’s piece is slightly sadistic. The artist takes the most poignant elements of Canova’s cemetery sculptures, the melancholic angels accompanying the deceased to the afterlife, and prints them to flatten the solidity of the marble. Closed in the plexiglas cage, the apparent eternity of classicism falls down, suffering the passing of time. Eternal youth dies hanging from a rope, becoming air: Aria.

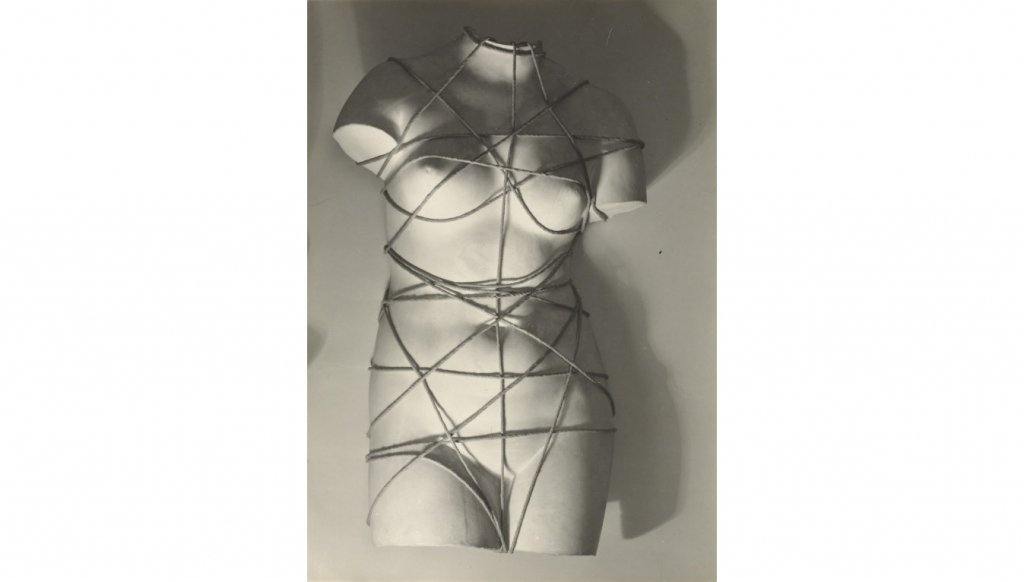

In 1936 Man Ray tied the torso of the Venus de Milo with a long lace, messing with “the most successful representation of beauty, the most perfect representation of the eternal feminine” as Théophile Gautier wrote in the 19th century. There is a sweet sense of humour in the act of squeezing the splendid flesh of that marble bust, or rather vulgar plaster, since Man Ray used a cast of the goddess made for the gardens. The Greek statue is dethroned. It loses all the iconic value of the classical ideal, becoming a simple perishable object, a found object.

Man Ray’s Vénus restaurée of 1936-71 is not far from Duchamp’s disorienting elevation of the famous urinal to a work of art. But Man Ray’s choice, while transforming Venus into a pure fragile body, defenceless flesh subjected to ruthless stretches of rope – with those breasts coming out of the laces, the pubis rubbed by the rope – creates a sense of anguish endowed with seductive power. Has the disregard to the classics created a body of flesh to crave?

Tying Bodies

Tying bodies is a very ancient practice in Japan. From the 15th till the 18th century, Samurais would immobilise prisoners with a rope instead of locking them in jails. In the 19th century shibari emerges as kinbaku, the technique of rope bondage, a place in between art and eros. The interweaving of rope and female body in Japanese culture creates a paradox: on the one hand, there is a highly erotic charge. On the other hand, there is a sense of pure, untouchable beauty typical of flower compositions (ikebana), which deal with a superior harmony and balance even through the vulnerability and perishability of a flower. In this regard, Shibari can be seen as the art of bodily composition, of all those rites and gestures pushing the limit between fragility and vigour through a rope.

Seiu Ito (1882-1968) is considered the father of kinbaku. The artist, who was heavily censored by the Japanese government in the 1930s and rehabilitated in the 1960s, very often used his second wife as a model. He famously tied her upside down while in an advanced state of pregnancy, looking for the most extreme poses. To put it in Western terms, his work combines the most unbridled Dionysism and the most lucid Apollonian sense, creating a unity between disinhibition and austerity, obscenity and purity, madness and discipline.

All this comes back with Lady Gaga hanging upside down, completely naked, while a rope wraps her in coils and draws lines through her flesh. The left leg, bent as in the Hanged Tarot, is tightened in several turns and knots of rope to suggest unnaturalness, almost mutilation. The arms are locked behind the back. The rope is tight on her deformed breasts, squeezing them on one side, making the nipples pop out on the other. She’s chewing and reciting words of the Marquis De Sade.

Flying is the title of the video, a performance filmed in black and white by Robert Wilson. The video was exhibited between 2016 and 2017 in Varese at Villa Panza di Biumo for the exhibition Tales, which consisted of 34 videos by Wilson about classicism. Some of these tableaux vivants had Lady Gaga as their subject: the face of the singer merges with that of Mademoseille Rivière portrayed by Jean-Auguste Dominique Ingres in 1806, or with the head of John the Baptist offered on a tray in the representation of Andrea Solari in 1507, or with the body of Marat in the Death of Marat by Jacques-Louis David in 1793, up to the erotic video Flying.

Lady Gaga has taken on the burden of becoming an interpreter of the art of others, like an alternative Christian deity drinks the bitter chalice of death to let herself be sacrificed for the artists who came before her. Her bondage is her sexual surrender, her garden of Gethsemane, where atonement in suffering between knots and suspensions allows her to be a loser and for this reason to prevail, taking charge of her monsters.

We come back to the ancient trope of the artist as god. Picasso said it clearly: “God, in truth, is simply another artist.” But even this Christian mimesis is nothing but a mise en abyme perpetrated by Bob Wilson through the endless thread of analogies, an infinite unrolling of the rope that binds the eternal moment of sex and death, of abjection and atonement, the fleeting sign of art as something to be always reinvented from scratch, in a concordant and heartfelt sursum corda!

Bibliography

- Gioacchino Barbera, Antonello da Messina, Electa, Milano, 1997

- Jean Starobinski, Ritratto dell‘artista da saltimbanco, Bollati Boringhieri, Torino, 1998

- Tzvetan Todorov, Goya, Garzanti, Milano, 2013

- Midori, La seducente arte del bondage giapponese, Airone Editrice, Roma 2002

- David Cordingly, Storia della pirateria, Mondadori, Milano, 2017

- Corrado Costa, Inferno provvisorio, Feltrinelli, Milano, 1970

- AA. VV., Alessandro Magnasco, Electa, Milano, 1996

November 25, 2020