Painting + photography according to Tatjana Danneberg

Tatjana Danneberg grabs fragments of real life, turning snapshots and drawings into complex paintings. Steyerl’s poor image lives again.

More than ten years ago, Hito Steyerl famously wrote a defence of the poor image. She described it as the image made by the non-professional, existing outside the official and the commercial worlds of images, the poor wretched of the screen, the illicit fifth-generation bastard from the territory of the many. Steyerl said the poor image was about reality. It no longer depicted it. She defended the poor image with her famous videos and installations. It seems to us that the paintings of Tatjana Danneberg take up this defence again, in fact making it more concrete.

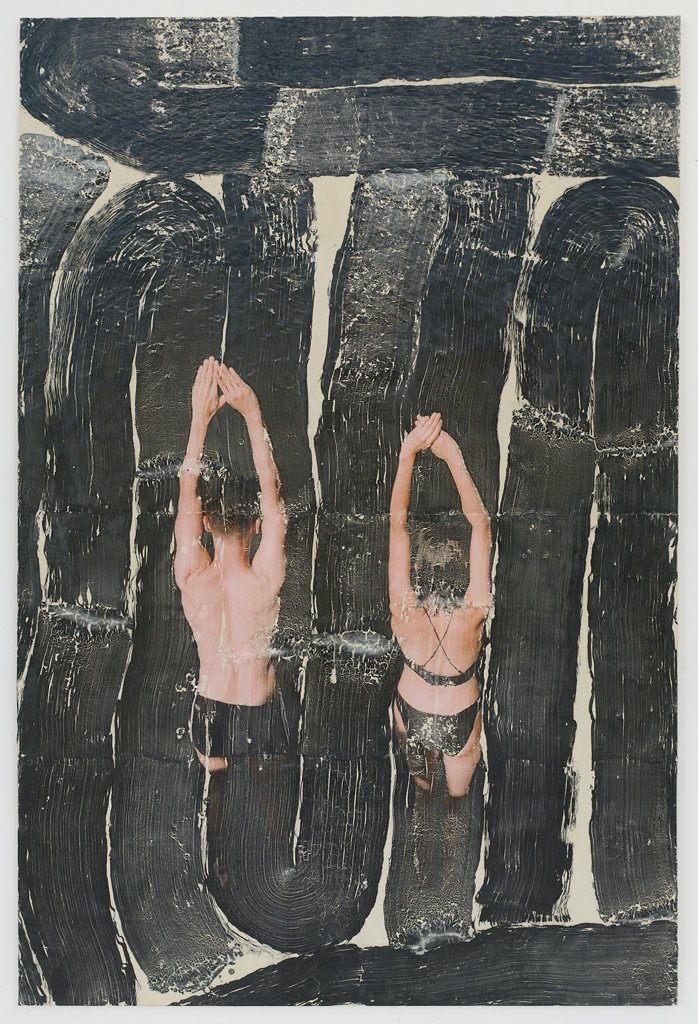

The emerging painter from Austria, currently living in Warsaw, brings the poor image into the material world in a way Steyerl didn’t explore. Her snapshots of daily life, taken with a cheap analog camera, are made into paintings. Not in a Richterian way, where the essence of photographs is sought with slight naivety through a mimetic translation onto canvas. Tatjana Danneberg’s process is complex instead. It involves things like gesso transfer, glue, printing on foil, large brushes. Poor images become rich objects. The easy technique of the analog snapshot–made with those “cheap 90s cameras where you just need to push one button” as the artist told us–are reworked through skills into complex pictures. So long to the poor image.

Respect

Tatjana Danneberg believes that photography is somehow uncomfortable. She says she can feel like an intruder stealing fragments of people’s lives, including her own. Banal situations, insignificant gestures, the reality of the poor image that Steyerl talks about: those are the things the artist calls (quoting Susan Sontag) “cutouts from the world.” What is the responsibility of the cutter one might ask. We think there is a form of respect in the act of painting appropriated fragments of life. It is as though the transformation of those snapshots into transferred compositions on canvas, which include planned brushstrokes, make for an act of reflection. Fading moments are taken away only to be given back somehow more alive.

We all keep objects for the way they remind us of a certain fleeting moment. Think of the teen dream embodied in a concert ticket, kept as a relic so the dream won’t leave. Another story is to create those objects. We can’t and don’t want to speculate about Tatjana Danneberg’s personal reasons for choosing those snapshots. However, we can look at those photographs and imagine their transformation into paintings as an act of restitution to the protagonists of the shots.

I don’t want to be a mere observer through the lens, but I somehow smuggle myself into the image by painting with or on it, so the image gets a second life.

There is passage from the private to public that needs some sort of justification. In this regard, the artist told us that it might be about “becoming a protagonist in something that has already happened, or that’s part of the past.” She continues: “I don’t want to be a mere observer through the lens, but I somehow smuggle myself into the image by painting with or on it, so the image gets a second life.” It is a way to look at photography from the perspective of a painter, which is ultimately the role that allows for a smooth pathway from private to public.

Photoless

All the arguments as built so far, the reference to the poor images of Hito Steyerl, make most sense in regards with the recent paintings of Tatjana Danneberg. Her practice arrived at those pictures after other experiments though, and it might as well depart from them in the future. We can imagine her using more complex cameras and more professional approaches to the photographic medium for example. Poor images might become rich images. What’s exciting about emerging artists is to ponder about how their work will evolve. We don’t want to claim a specific interpretation is all there is to a young practice, although we hope that this interpretation won’t completely fall short.

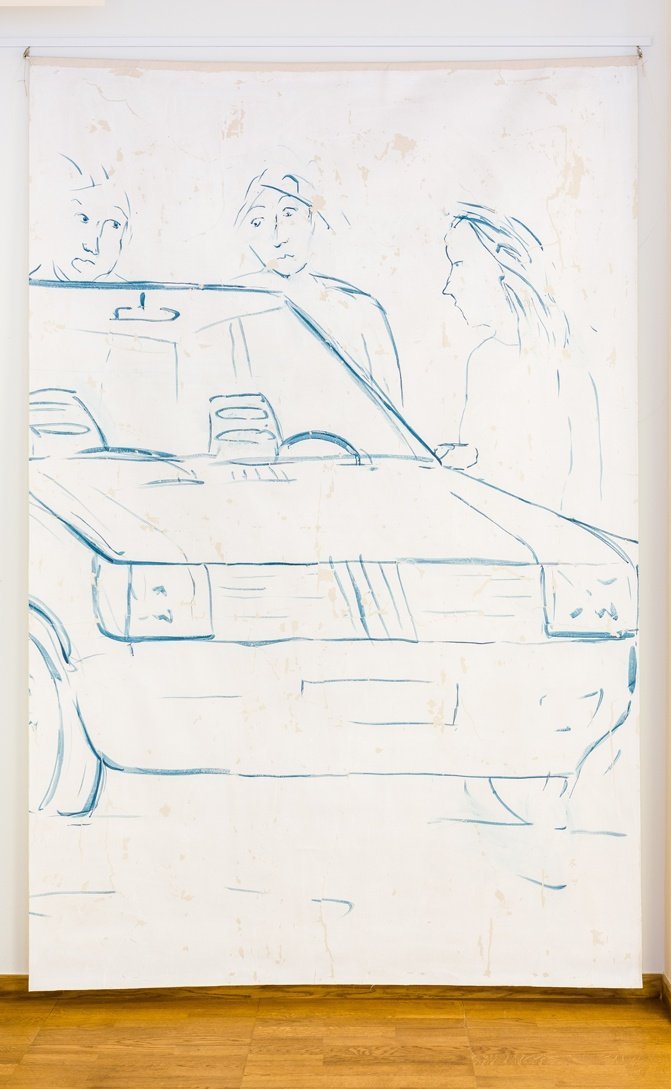

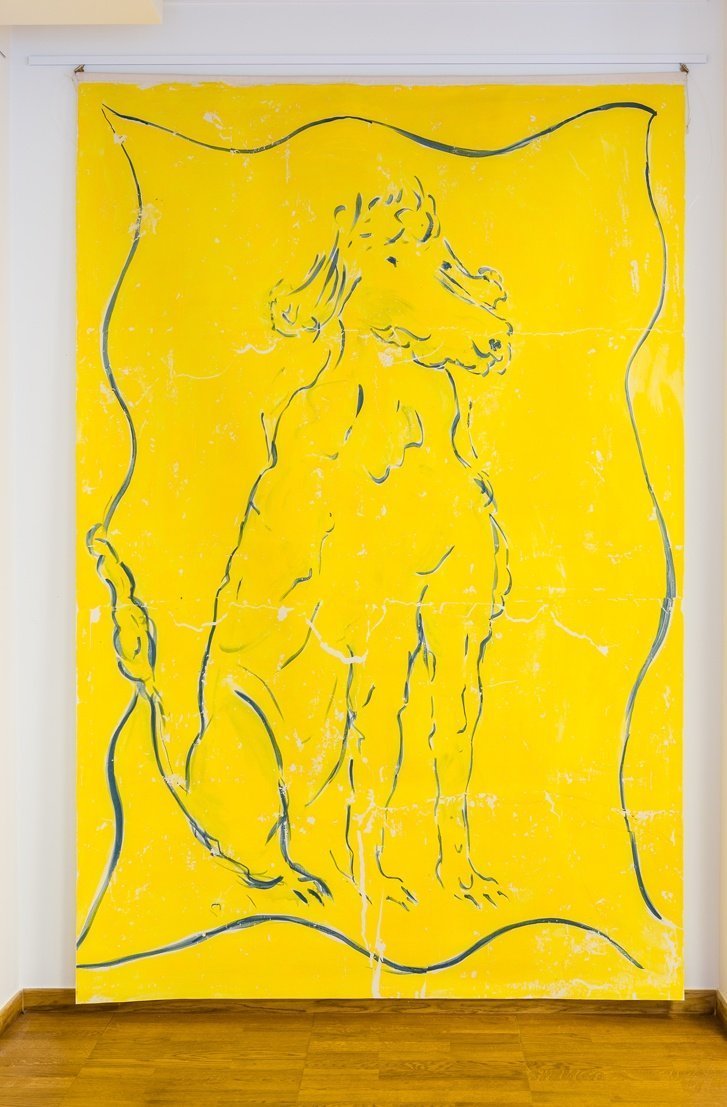

Looking at her works without photography, we can try to connect it to her work with it. Paintings like Sheepish, Constantly no respect, and Uno lack any photograph per se, only consisting of transferred drawings on canvas. The nature of those subjects is however tied to the reality of Steyerl’s poor images. Sheepish is not so much the depiction of a dog as it is about the reality of a dog, perhaps caught in a fleeting pose just like the three figures standing next to an iconic Fiat Uno. The image of a Cacio & Pepe plate of pasta in the homonymous painting feels personal. There is something as intimate in those drawings as in the snapshots, both being enlarged for the public through the painterly medium.

Rhythms and Stories

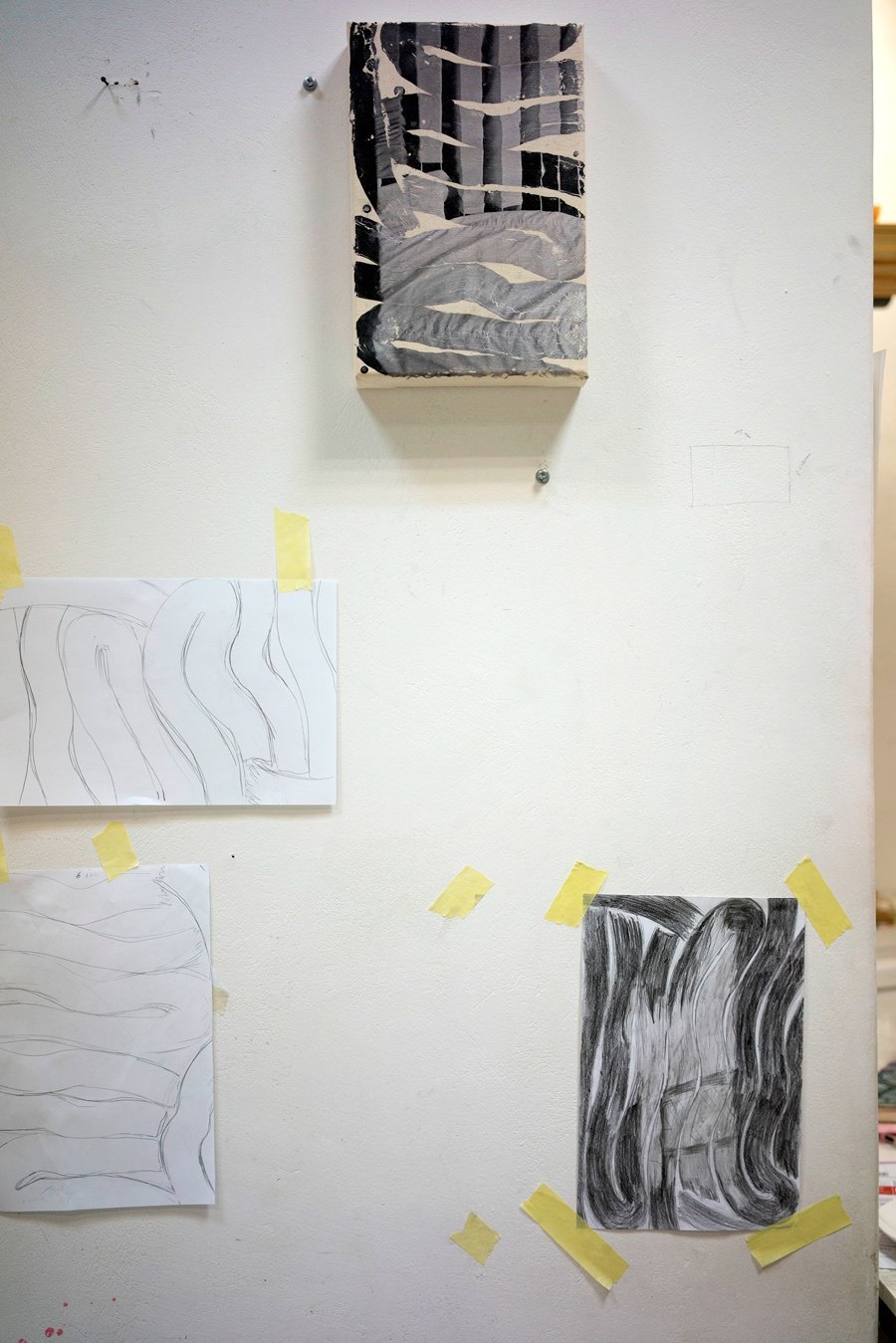

Images might be casual but the paint is controlled. The wretched becomes well-built. Compositions are thought through beforehand. We learn from the artist that the gestures happening on the foil are planned in preparatory drawings before they get transferred on canvas. She says: “with big brushstrokes I want to have clear gestures that are referring to what is happening in the image, which can be shaped, formed, liquified.” The contrast between the lightness of things like ducks and jeans on the one hand, and the curvy, large brushstrokes on the other, confirms this sense of afterlife given to appropriated pieces of daily reality.

The planning happens both on and off the canvas. For a few of her projects, Tatjana Danneberg looks at composition and coherence at the level of the exhibition too. With regards to her recent show at LambdaLambdaLambda in both Pristina and Brussels, she mentions that “the selected photographs show some form of random synchronisation, movement, and body language in a social context. Even if the paintings are not staged, they could form something like an improvised choreography together, or some weird storyboard.” The idea of choreography and indirect theater stage comes back also in past series of hers: One Step Behind You (2018) inspired by a Beckett’s play and Six Characters in Search of an Author (2018) from the homonymous Pirandello’s work.

Real Life

Poet Max Henry says painters are time travellers. The medium seems immune to withering, unlike photography. We wonder how Steyerl’s treatment of the poor images will feel in a few decades. The quintessentially poor image in her defence is the digital one, which is treated as such through video in her work. Steyerl’s manipulation and defence of the poor image remains in the realm of the poor image. Video artists are worse time travellers than painters. Their work tends to age fast, just like the planned obsolescence of the devices they use. [Here is the link to our writing about Post Internet label premature death. Ed]

There is something evergreen in the apology of the poor image by painters/time travellers like Tatjana Danneberg, even more when one realizes how her paintings can’t be translated for the screen. How can a phone reproduce the experience of the material coming off the canvas? How can it render the cracks of the transferred foil? This thought experiment becomes even more interesting when the poor image is a drawing instead of a snapshot, as it happens across Danneberg’s practise.

Perhaps we have reached the time where poor images don’t need to be defended anymore. It is no longer 2007: the poor image is no longer alien to state propaganda or exploitation, as Steyerl maintained back then. Yet the poor image seems to still need public rehabilitation, a new look, which is a new look for reality itself. The paintings of Tatjana Danneberg provide an excellent way for this sort of visual refurbishment.

May 12, 2022