Margaret Lee: What You See Is What You Mean

Thinking through Margaret Lee’s recent paintings in light of the compound visual language the artist has been developing over the past decade.

There is something unsettling about a painting that starts off by telling you that it sees what you mean. It appears that the nine paintings in Margaret Lee’s cunningly titled suite I.C.W.U.M. are paying attention, they know the feeling, they hear you. How uncomfortable! Facing a work that seemingly complies without expressing a clear opinion certainly complicates any inquiry into the source of signification. We are used to wanting art that challenges us, not art that acquiesces in our desires, demonstrates concern with brief affirmations and lets us do the talking — what do you mean you see what I mean…

Margaret Lee, I.C.W.U.M. #1, 2019, newspaper, oil paint, oil pastel, rope on canvas, 49 1/2 x 36 1/2 inches. Courtesy of the artist, and Misako & Rosen, Tokyo. ©Margaret Lee

Margaret Lee, I.C.W.U.M. #2, 2019, newspaper, oil paint, nails on canvas, 48 1/2 x 36 inches. Courtesy of the artist, and Misako & Rosen, Tokyo. ©Margaret Lee

Margaret Lee, I.C.W.U.M. #3, 2019, newspaper, oil paint, oil pastel, nails on canvas, 48 1/2 x 36 inches. Courtesy of the artist, and Misako & Rosen, Tokyo. ©Margaret Lee

Margaret Lee, I.C.W.U.M. #4, 2019, newspaper, oil paint, rope on canvas, 48 1/2 x 36 inches Courtesy of the artist, and Misako & Rosen, Tokyo. ©Margaret Lee

Margaret Lee, I.C.W.U.M. #5, 2020, newspaper, oil paint, rope on canvas, 48 x 36 1/2 inches. Courtesy of the artist, and Misako & Rosen, Tokyo. ©Margaret Lee

Margaret Lee, I.C.W.U.M. #6, 2020, newspaper, oil paint, nails on canvas, 48 1/2 x 36 inches. Courtesy of the artist, and Misako & Rosen, Tokyo. ©Margaret Lee

Margaret Lee, I.C.W.U.M. #7, 2020, newspaper, oil paint, rope on canvas, 49 x 37 inches. Courtesy of the artist, and Misako & Rosen, Tokyo. ©Margaret Lee

Margaret Lee, I.C.W.U.M. #8, 2020, newspaper, oil paint, oil pastel, rope on canvas, 49 x 36 inches, courtesy of the artist, and Misako & Rosen, Tokyo. ©Margaret Lee

Margaret Lee, I.C.W.U.M. #9, 2020, newspaper, oil paint, rope on canvas, 49 1/2 x 36 inches. Courtesy of the artist, and Misako & Rosen, Tokyo. ©Margaret Lee

At first sight, a painting like Lee’s I.C.W.U.M. #1 shares some of the cool nonchalance of Michael Krebber’s MP-KREBM-00068 or MP-KREBM-00089. Yet in spite of their loose brushstrokes and easygoing attitude, Lee’s paintings come across as caring. “Don’t pretend you don’t work hard” a painter’s painter like Rebecca Morris would say. But while these paintings would have us situate them within the painterly realm of painting, accounting for Lee’s previous work makes for a more complex equation — an equation as complex as the multifaceted nature of her activities. Indeed, Margaret Lee is at once an artist, an art-worker, co-founder of the gallery 47 Canal, and an engaged community member in New York’s Chinatown neighbourhood. Margaret Lee cares, and she undeniably works hard even as she addresses us with double negatives like It’s not that I’m not taking (this) seriously in the title of her 2016 exhibition at Jack Hanley Gallery.

Margaret Lee, I.C.W.U.M, installation view, LA MAISON DE RENDEZ VOUS, Brussels, Belgium, 2020. Courtesy of the artist, and Misako & Rosen, Tokyo / LA MAISON DE RENDEZ VOUS, Brussels. Photo credit: Isabelle Arthuis.

Margaret Lee, I.C.W.U.M, installation view, LA MAISON DE RENDEZ VOUS, Brussels, Belgium, 2020. Courtesy of the artist, and Misako & Rosen, Tokyo / LA MAISON DE RENDEZ VOUS, Brussels. Photo credit: Isabelle Arthuis.

Margaret Lee, I.C.W.U.M, installation view, LA MAISON DE RENDEZ VOUS, Brussels, Belgium, 2020. Courtesy of the artist, and Misako & Rosen, Tokyo / LA MAISON DE RENDEZ VOUS, Brussels. Photo credit: Isabelle Arthuis.

Margaret Lee, I.C.W.U.M, installation view, LA MAISON DE RENDEZ VOUS, Brussels, Belgium, 2020. Courtesy of the artist, and Misako & Rosen, Tokyo / LA MAISON DE RENDEZ VOUS, Brussels. Photo credit: Isabelle Arthuis.

To contextualize I.C.W.U.M. we can also look at her 2016 collaboration with the Dallas Museum of Art and Duddell’s. At the occasion of the DMA’s Concentrations series’ 35th anniversary, she created a series of works for the Hong Kong-based Michelin star restaurant. Amongst these works were photographs slickly produced as dye sublimation on aluminum splattered with Jackson Pollock-like drips of black acrylic paint. The photographs were of high-end sinks, drains, shower heads, faucets, and an occasional Brancusi sculpture photographed at the DMA. Titled with another mis-initialized acronym W.D.U.T.U.R. these works casually asked restaurant goers Who Do You Think You Are? On the imposing stone walls of this gourmet establishment, Lee’s pictures and their titles suggested an intent similar to that of Marcel Duchamp’s infamous pun on the Mona Lisa with his L.H.O.O.Q. (pronouncing as “she is hot in the ass” in French), which some understood as an attempt to freak-out the bourgeoisie. Lee’s restaurant art brought the bathroom a bit closer to your meal and art a bit closer to the bathroom.

Margaret Lee, Who Do You Think You Are (shower), 2016, installation view, Duddell’s x DMA: Concentrations HK: Margaret Lee, Hong Kong. Courtesy of the artist and Duddell’s.

Margaret Lee, Who Do You Think You Are (shower), 2016, Dye sublimation photograph, plaster, ceramic, wood and acrylic paint, 43 x 30 x 1 inches. Courtesy of the artist, Jack Hanley Gallery, New York, and Misako & Rosen, Tokyo. ©Margaret Lee

Margaret Lee, Who Do You Think You Are (sink), 2016, installation view, Duddell’s x DMA: Concentrations HK: Margaret Lee, Hong Kong. Courtesy of the artist and Duddell’s.

Margaret Lee, W.D.U.T.U.R. #1, 2016. dye sublimation photograph and acrylic paint, 42 x 28 inches. Courtesy of the artist, Jack Hanley Gallery, New York, and Misako & Rosen, Tokyo. ©Margaret Lee

Margaret Lee, W.D.U.T.U.R. #3, 2016, dye sublimation photograph and acrylic paint, 42 x 28 inches. Courtesy of the artist, Jack Hanley Gallery, New York, and Misako & Rosen, Tokyo. ©Margaret Lee

Throughout her work, Margaret Lee has often played with the fine line between readymades, objets trouvés and fabricated or altered objects to question modes of display and to study the relationship between art and design in light of class and gender issues. Whether we are meant to understand her I.C.W.U.M. paintings as part of her broader object and image-based practice or take (them) seriously as paintings is as elusive as the title they put forth. To choose would be to bypass the strenuous but productive ambiguity the work entails. Don’t forget that they see what you mean and that they are ok with your opinion anyway. Sporadically adorned with pieces of thick rope running on their edges, Lee’s canvases willingly flirt with the decorative taste that would suit the lush interior of a seaside house in The Hamptons or an apartment in Belgium’s Knokke-Heist.

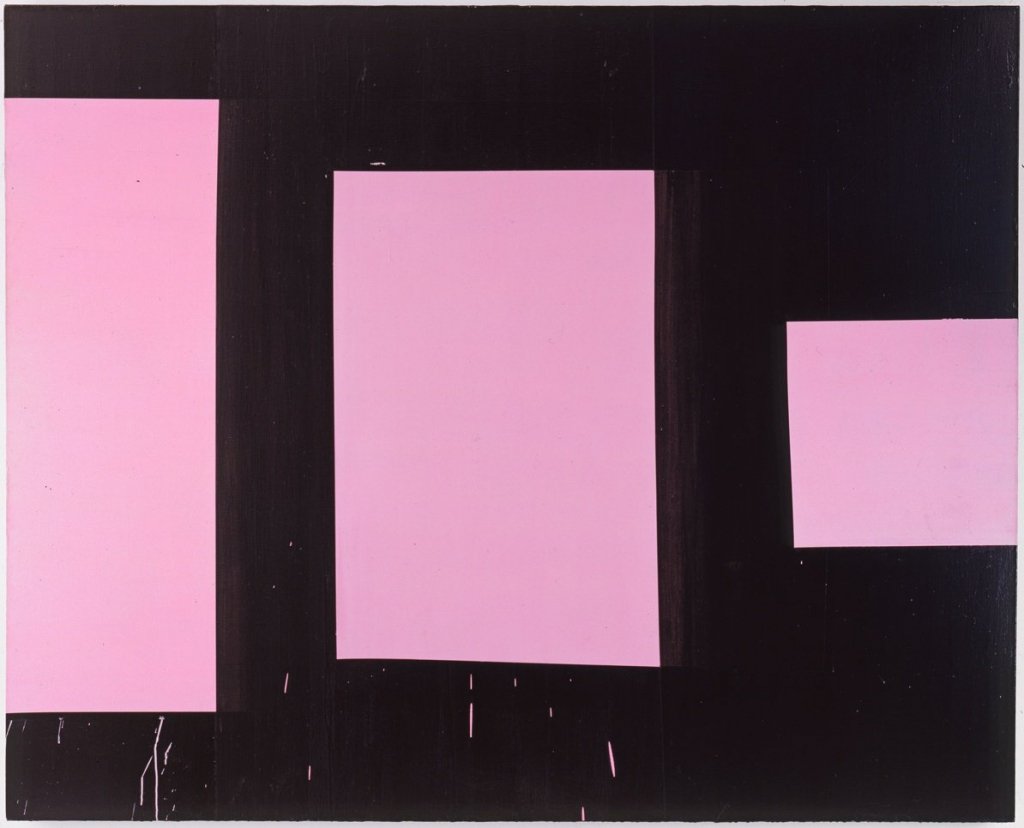

Margaret Lee’s paintings are sexy and they know it. Their rhythmical arrangements of pinks and blacks remind us of Mary Heilmann’s iconic new wave painting Save the Last Dance for Me (1979). Bringing abstract painting closer to life by highlighting its proximity to music and design, Heilmann poked a hole through the prevailing endgame logic of late modernism. In a male-dominated art scene, she asserted “You want beauty, I’ll give you beauty!” Painted over pieces of ripped newspaper collaged onto the canvas, Lee’s paintings have a ludic and patchy quality. It feels odd yet relevant to point out that they are visibly handmade. Most evident in I.C.W.U.M. #3 and #8, the collaged pieces of newsprint act as a crafty substrate that seems to have provided a rational for how the paint was applied to the canvas. Lee literally covered the news.

The patches of paint, the newsprint and the rope are the only identifiable referents in I.C.W.U.M. However, all three of these elements have precedents in the artist’s exhibitions. In closer to right than wrong / closer to wrong than right (2014) she covered white replicas of modernist furniture with her signature Dalmatian black dots. And in her 2018 exhibition Shouting in a Bucket Blues, an open edition wall vinyl of a rope graphic hovered next to a large papier-mâché sculpture of a cloud coming out of a pipe inserted into the wall.

Margaret Lee, Shouting in a Bucket Blues, installation view, The Green Gallery, Milwaukee, WI 2018. Courtesy of the artist, and The Green Gallery, Milwaukee, WI.

Margaret Lee, Shouting in a Bucket Blues, installation view, The Green Gallery, Milwaukee, WI 2018. Courtesy of the artist, and The Green Gallery, Milwaukee, WI.

Margaret Lee, closer to right than wrong / closer to wrong than right, installation view, Jack Hanley Gallery, New York, 2014. Courtesy of the artist, and Jack Hanley Gallery, New York.

These recurrent symbols and referents hint to the idea that these paintings are also devised as objects. As common objects, paintings are able to carry symbols and meaning in embodied and surreptitious ways because they are symbols in and of themselves. Paintings are movable, transferable, docile yet resilient. Paintings make their way into your life and onto your walls, they hang next to you at the restaurant and show up on your screen or on your way to the restrooms. They’re the next thing you want to go with your houseplant, your Gerrit Rietveld Zig-Zag chair and your Superstudio-inspired nesting tables. But paintings don’t have to be comfortable armchairs, they can also be good appliances, like your vacuum cleaner or the old toaster oven you never clean — you can push their buttons, pull on their ropes, and they’ll outlast their three-year warranty. Like a smart connected object replying with Sorry, I didn’t quite get that, Margaret Lee’s I.C.W.U.M. paintings manage to produce states of ambivalence that keep us engaged, even when we are not sure if we are being heard.

December 8, 2020