Sophie Gogl: relating to the smiley face

On Sophie Gogl’s love for turns, seeking what’s behind her gimmicks and reaching the top of the pyramid of needs

In the pyramid of needs established by psychologist Abraham Maslow, the possibility of self-fulfilment stands on the very top, given that all of the needs below are satisfied. For him, it’s about reaching the individual’s full potential and growing into one’s most inventive and creative version of oneself. The tools that Maslow discusses to get to this point relate to the works of artist Sophie Gogl (b. 1992, Austria).

Writing about his understanding of self-actualization, Maslow speaks of transcending human consciousness by relating to oneself as well as to significant others, to human beings in general, even to other species. (1) It is through the lens of said pyramid that we will examine tendencies and examples from Gogl’s recent works and exhibitions.

Stemming from a craftspeople family, Sophie Gogl is still living and working between Kufstein in Tyrol and Vienna, the two places between which she spent most of her time growing up. The artist is often found lingering at the hazy and hybrid border between painting and sculpture, somewhat her mediums of choice. Yet her practice always allows for digressions into other fields such as writings, video works, or even more utilitarian objects such as curtains or lamps.

When it comes to the work of Sophie Gogl, a clear set of overarching topics might not be immediately evident. This is probably because her creativity is recurrently rooted in reflecting her sources of inspirations and interests themselves. Often echoing streams of consciousness and thereby not distinguishing or judging their origin–they could easily be trends from social media or behaviour and habits of her peers–the artist assumes the role of a catalyst.

Gogl likes to illustrate what she perceives to be a canon. However, by depicting and therefore manifesting, almost perpetuating certain motifs, the artist seems to achieve the contrary effect. She repeatedly provokes tension within her work, positioning her pieces as somewhat stuck in time. In between a contemporary and ever-accelerating stream of images and previous traditions of depiction, especially in the historical context of oil painting, Sophie Gogl always walks a tightrope, balancing.

Some of her most recent circular paintings show that she is more interested in commenting rather than imposing. Having previously translated online culture phenomena such as memes into paintings, these new works, which look like colourful cans eerily placed into the exhibition space, remind of Andy Warhol’s gesture of famously and similarly appropriating familiar images from consumer culture and mass media, among which is his widely consumed canned soup. (2)

There exist previously defined roles for artists. One of them is to replicate and evoke questions of authority, including the authority supposedly given to artists themselves once they are asked to exhibit. Gogl is interested in unpacking this role with her work. She, at once, intensifies and neglects this feeling of being on a educational mission.

Regularly, her work shows animal bodies opposed to their human counterparts, not too seldom fulfilling similar tasks. She criticizes feelings of human superiority, suggesting that we are ultimately not that different. Animating various other characters in her paintings, she ultimately calls into question if we, as humans nowadays, or as artists, can even uphold or rise to said authority without bias.

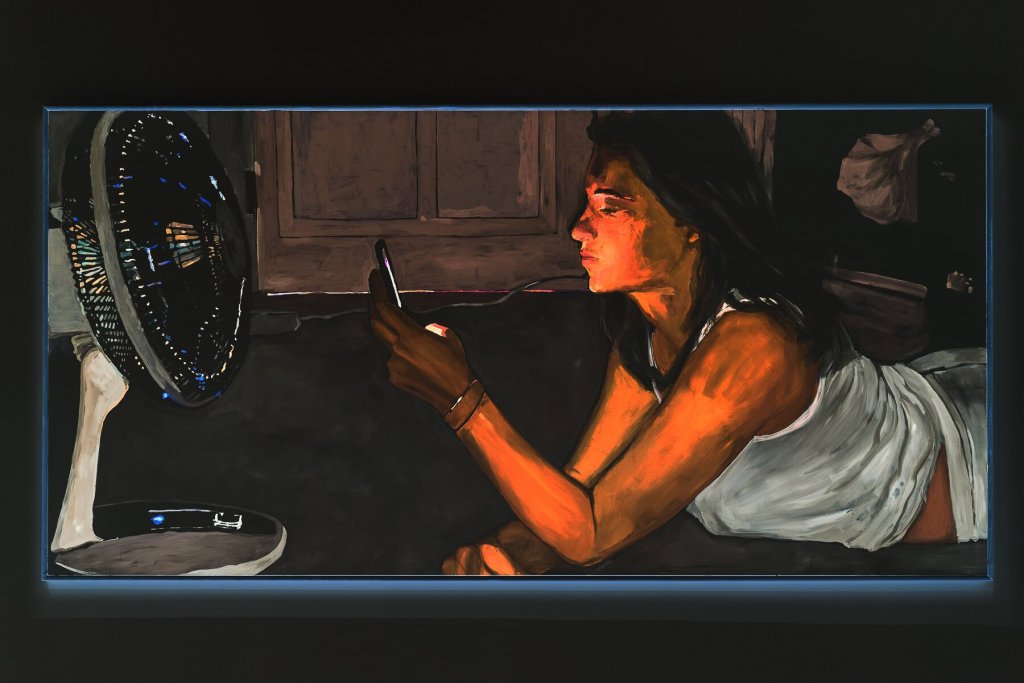

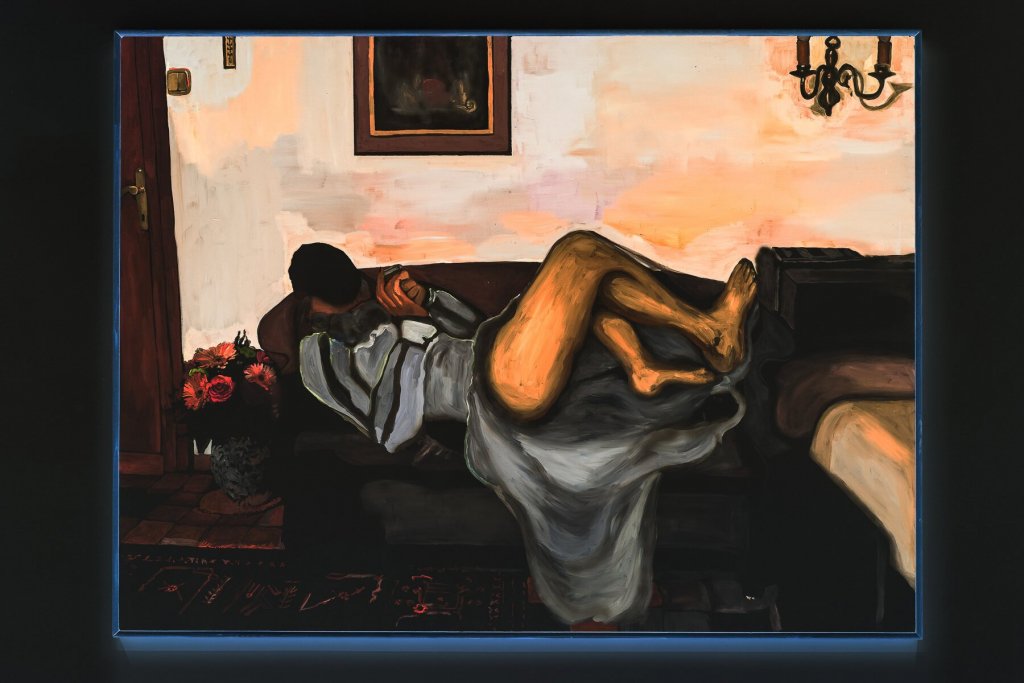

In her exhibition “Secondhand Angst” at gallery Zeller Van Almsick, we encounter exactly the kind of digressions mentioned in the beginning. Playfully appropriating elements classically attributed to the field of photography and the possibilities of its postproduction in the digital age (inverting the colours of an image for example), Gogl intentionally paints some of her canvases with negative hues.

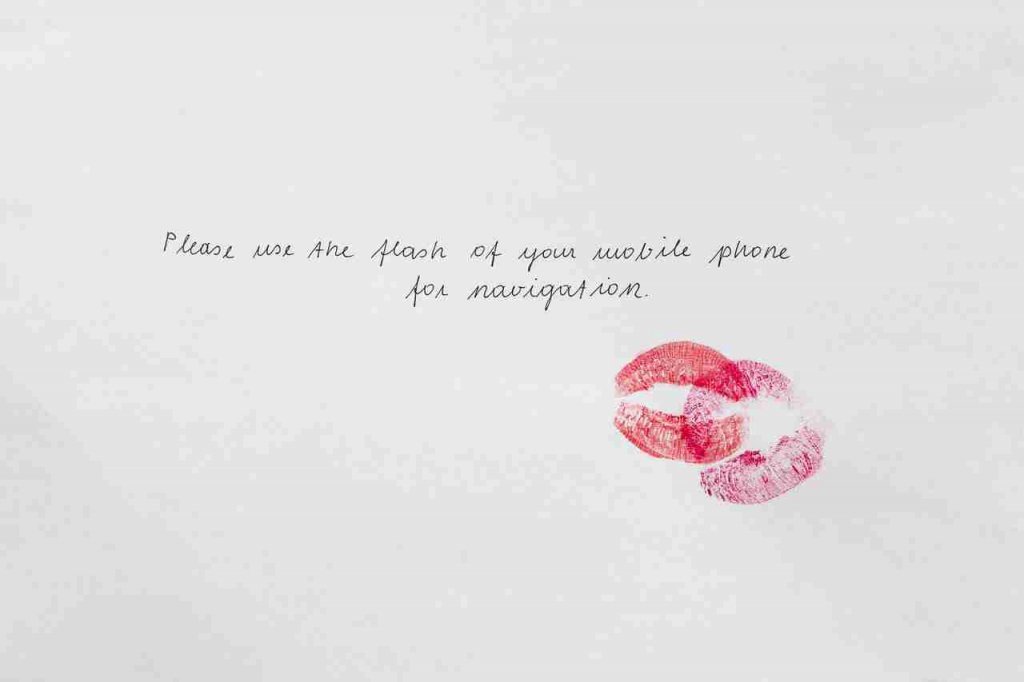

Another room, darkened and sealed from any form of light, is preceded by a note that resembles a love letter by Frida Kahlo, carefully equipped with two differently coloured and perfectly applied kiss stains, along with a written advice to the visitors to use their smartphones for navigation.

However, the smartphones in the case of this exhibition are not only used to illuminate the space or possibly invert an image, but are also one of the main protagonists depicted in many of the paintings alongside the body of the artist herself. With visitors functioning as the last parts of a somewhat constructed yet interactive play revolving around converting, copying and replication, this show serves as a great example of how the artist experiments with her sculptures and with extending the pictorial space, ensuring a livelier and more agile experience of her works.

A bit less vivid in the spatial experience and even more morbid in terms of content was the installation “Storno”, commissioned by the Museum of Applied Arts in Vienna in the context of their ongoing “Creative Climate Care” series. Continuously interrogating not only the position of the artist within sensationalist, giddy and essentially wasteful environments, but generally pointing at the production of this very iconography within the arts, the mirroring function of “Storno” is unambiguously evident.

Surprisingly, in a conversation prior to this text, Gogl stated that this particular show indeed turned out to be more about femicide than climate change or consumerism–a turn of events that the artist did not intend but couldn’t dismiss either. All of a sudden it makes a lot of sense that singer Lana Del Rey is peeking out of one of the many suitcases scattered throughout the basement space. As one of Del Rey’s most successful albums and an eponymous song are titled “Born To Die”, one can’t help but smirk a bit. The question of what actually happens in the reproduction and modification of popular images into new entities constituting new images that feed new algorithms however remains unaddressed. All we are confronted with here are leftovers of symbols and narratives, tales of a once lived reality.

Visceral abstractions and theoretical traditions could further help to locate some of the decisions in respect to representation within Gogl’s pieces. Says literary critic Sianne Ngai: “The smiley face rather expresses the face of no one in particular, or the averaged-out, dedifferentiated face of a generic anyone. It calls up an idea of being stripped of all determinate qualities and reduced to its simplest form through an implicit act of social equalization, relating every face to the totality of all faces.” (3)

Although in our case there is not literally a smiley face, by extracting Ngai’s argument and applying it to our subject, we eventually fold back to the suggested Maslowian way of reading Gogl’s work. We also find this take in one of Gogl’s latest writings called “She brings the pain”. In this text piece – which was published with Schwabinggrad in Munich in the context of a show that held the same title – she includes the story of a boyfriend trying to align himself with contemporary discourses about gender and who is consulting his girlfriend about it. The zine-style booklet also contains some screen grabs of Instagram stories, one of the main ways of relating to one’s peers in today’s society.

Sophie Gogl loves to relate. Just like the way she turns her round canvases as she paints them, she also allows herself to take turns when it comes to the subjects of said relations within her practice. In endless circular movements, like plane turbines propelled by a relentless motor, she thereby escapes the need for legitimisation. She processes her starting material, a variety of inspirations often rooted in societal patterns and current circumstances, ultimately transferring them into her mediums of choice. And as we, the viewers and bystanders, might not be invariably sure of what is disguised behind all the gimmicks, as we are not aware of what processes have not surfaced to the tip of the pyramid yet, we simply remain eager to wait and see what comes next.

***

(1) The farther reaches of human nature, Abraham H. Maslow, 1971, p. 269.

(2) The work referred to is “Campbell’s Soup Cans” by Andy Warhol, 1962.

(3) Theory Of The Gimmick, Sianne Ngai, p. 175-176

January 28, 2021