Josefine Reisch: if history is a stage

Josefine Reisch and not letting yourself “become part of the killer story.” An essay inspired by the carrier bag theory of Ursula K. Le Guin

When a story is nearing its end, we’d better start telling another one. “The trouble is,” according to Ursula K. Le Guin, “we’ve all let ourselves become part of the killer story.” A story shaped as a weapon – a bone, an arrow, a sword or a spear – forged for and held by the hero to hunt, kill, and ultimately write his bloody tale as a victor. Browsing through history books, or Wikipedia pages, we’ve all come across such things – “things to bash and poke and hit with, the long, hard things.” What we haven’t heard of is the item, or device, where things are gathered: the container of the story – the bag. It’s the tool that allows one to collect and store; to bring energy in, instead of forcing energy out. [1] For Ursula K. Le Guin, as for Josefine Reisch (born 1987), the bag is where uncharted narratives come to light, through which another story – with unnamed characters and secret perspectives – starts to take shape.

The bag is an equalizing force; there are hardly any hierarchies inside it. Things get easily lost, but then are always found. They get entangled and their trajectory is erratic; they seem to move in whirlwinds, not so much in linear ways. Here, heroes and conquerors, kings and emperors have no plinths to stand on, so they start to mingle with house keys and trinkets, with jewelry and junk. Through a cognizant playfulness in the face of historical truths, Reisch deconstructs objects of power, piercing the obvious and the self-evident. Her work deliberately eludes what is already given by European history – which often overlaps with male-centered accounts – to understand the structures underlying the birth of ideals, ideologies and myths, criss-crossing between eras, references and interests to mix them into a different song – or a medley, a mash-up, a compilation.

While the carrier bag of history may have dissolved or disappeared as an item, frayed by the passing of time, squashed by the main storyline, the teachings of “the feminist way to gather” and their legacy are alive and well. Despite her interest in Le Guin’s theories, Reisch’s passion for historiography has to do with her origins. Her family was from the German Democratic Republic, the Eastern part of Germany. “At the moment, some people would think of this as being something interesting, whereas shortly after the fall of the wall it was completely uncool. Nobody cared about it.” Zeitgeist-y phenomena such as these – when a single event or situation can be read in many ways – are what draws the artist to look at the world through the lens of historiography, and to challenge assumptions around authenticity. Still, most of what she does has analytical intentions, rather than autobiographical. “What actually happened is always questionable, especially when it’s further back in the past. It’s almost up to fashion and trends how you show and tell stories.”

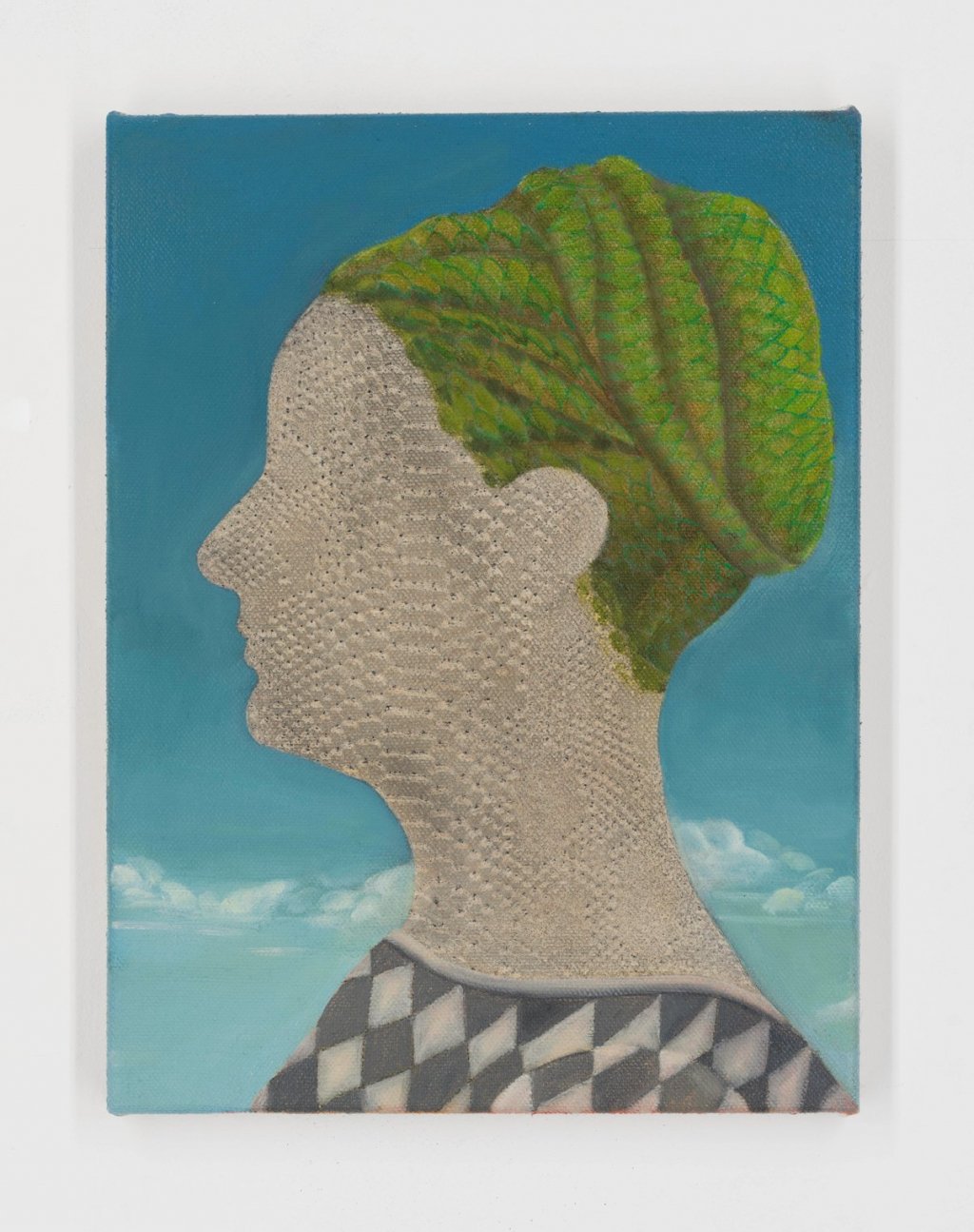

Thinking about the female image, and how its perception and design has changed in the course of the centuries, Reisch identifies the Renaissance, a period that holds a particular charm for her due to its “cosmopolitan momentum,” as a breaking point for its influence on female portraiture. “What I always loved about these paintings, which also appeared on coins, is the side profile.” Neither seductive nor passionate, the subjects in these portraits stand unmoved, their gaze never meeting that of the viewer. Their names, however, have mostly been forgotten, and the loss of identity seems to be accompanied by a scarcity and fleetingness of political power. A relationship that Reisch has extensively explored in her work is that between the history of portraiture and today’s practice of selfie-taking and publishing as a means of self-representation and promotion, which is dotted with contrasts and analogies; among the latter is the issue of objectification. For the artist, what has actually changed since then is merely the quantity of portraits produced, and the consequent shift in terms of value. The empowerment that purportedly follows visual, and physical, self-promotion, instead, remains debatable. “Selfie-taking is empowering because you can do it – that’s for sure.” The question, for Reisch, is “where that leads you.”

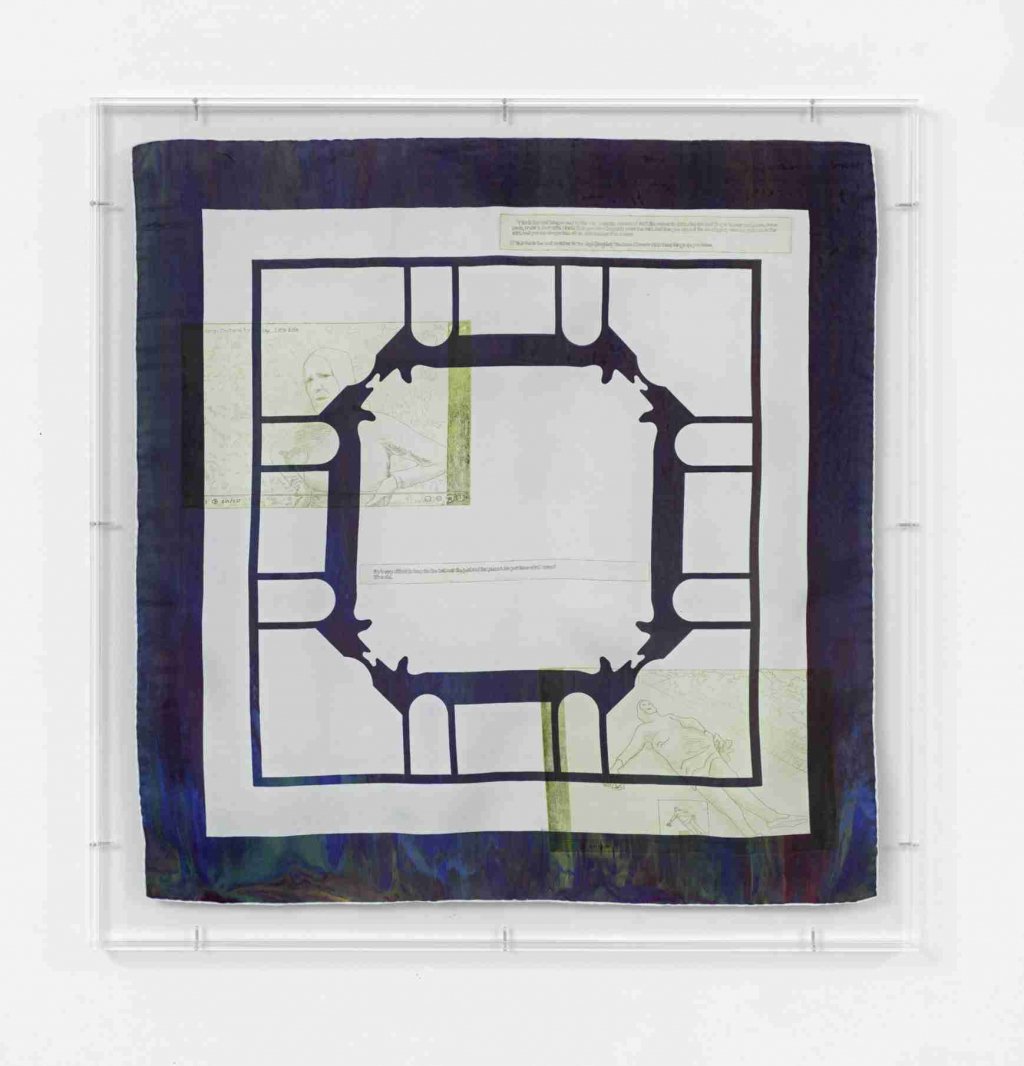

Exploring the context of presentation of portraits and interrogating their form, as she did in her series Framing (2020), first exhibited in Berlin at Noah Klink, is a way for Reisch to dissect sources of authority, which may be both institutional – as with museums – and object-based – in the case of picture frames. But her interest in history, profiles and frames is both conceptual and formal. The meticulousness through which Reisch examines decorations, embellishments and trimmings while researching past iconographies and trends is strictly tied to her quest to understand the dangers and powers of ideology, and how it impacts the production of value. “When I think about value I also think about validity – how is that value generated.” With the development her 1:1 cut-out sheet paintings, a significant part of the process is getting to know an object’s design. The first one she made was a reproduction of Napoleon Bonaparte’s desk. In Jacques-Louis David’s The Emperor Napoleon in His Study at the Tuileries (1812) “there’s the desk, and he’s in front of it.” Reisch found out that Napoleon largely influenced its design: he decided what kind of animals and ornaments should be on it, as well as their placement. Plus, she says, the desk had “a funny function”: when it looked messy, it could just be folded down. That way, it looked like Napoleon never had to work.

“There’s this moment when you realize it’s really good to know your enemy. If you move into a scary house, you have to walk in every room, look in every cupboard, and step into the basement. Once you’ve seen everything, you’re not scared anymore.” Reisch’s practice is entrenched in the demystification of how legends come to be. In an attempt to grasp the erasures of history, the artist scrutinizes the way stories are told, influenced, manipulated, spanning from Hollywood biopics to historical reports, wondering how they could have unfolded otherwise. She describes her approach as being “a bit like a reenactment… a way to get to know it and change it a little.” In fact, Reisch got in touch with art and art-making through dramatic arts. Both her parents are artists; her mother studied painting, while her father works in theater as a stage designer. During her childhood, Reisch would often follow him to his workplace, where, throughout the years, she ended up watching loads of plays – something that turned out to be instrumental for the establishment of her practice later on.

Within the framework of traditional theater, the concept Reisch has always been fascinated by belongs to the Brechtian tradition. “There, the stage is not something that blends into reality or tries to engage with your emotions. It’s really like a border. There’s no catharsis; there’s a distance and perspective on whatever you think about.” Bertolt Brecht’s theory of the estrangement-effect – which, together with its political implications, is among the artist’s main influences – aims to recognize and contextualize an object’s essence as historical, as opposed to natural or immutable: namely, as having been caused by (and altered across) time. While Reisch’s engagement with the interpretation of history is bound to “the layers of meaning and misreadings” it opens up to, what she loves about the stage is how it offers the “possibility of illusion.” The title of one her works, a screen print and etching on silk from 2020, eloquently speaks about Reisch’s view on the function of illusion and fantasy over one’s perception of truth in time, history, and, more generally, reality. It’s very difficult to keep the line between the past and the present. Do you know what I mean? It’s awful. These words were spoken by Edith Bouvier Beale, the cousin of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, in the 1975 documentary Grey Gardens. In the film’s production years, Little Edie and her sister lived in a house populated by raccoons, badgers and fleas, without running water. Although their wealth had been depleted, they kept their “grand dame attitude,” the artist says, adding that “ostentation and luxury can be a fantasy.” It is the story that makes the difference.

Similarly, within Reisch’s paintings, the illusion created by gilded ornaments, legendary characters and grandiose endeavors becomes the means to tell a story that, sometimes, may not even exist. Working with history, like she does, is about refusing to serve the facts that have risen to the surface as certainties. It is an act of dismantling – of breaking down walls and barriers – to unearth what has always been there, just hiding all along. “Since history is the endless process of human creation,” it is, for the same reason, the “unending process of human self-discovery” – akin to self-creation, or autopoiesis, as Zygmunt Bauman writes. [2] A notion that grasps and encapsulates “the gist of the human condition,” autopoiesis intersects with Reisch’s unwillingness to give in to orthodox storytelling, or to the reverberations of the tale of the hero and his spear in our present day. Instead, in a world where “creation is the sole form discovery can take,” her art makes room for, and gives form to, discovery through self-creation, while being the source – and not the object – of an act.

[1] Ursula K. Le Guin, 1986, The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction. Available at https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/ursula-k-le-guin-the-carrier-bag-theory-of-fiction

[2] Zygmunt Bauman, Liquid Modernity, 2000, Cambridge: Polity Press, p.203

June 7, 2021