Latifa Echakhch and seeing things as if they’re vibrating (an interview)

Latifa Echakhch on her upcoming pavilion at the Venice Biennale, her recent inclusion in the Swiss Institute board, and intimate artwork

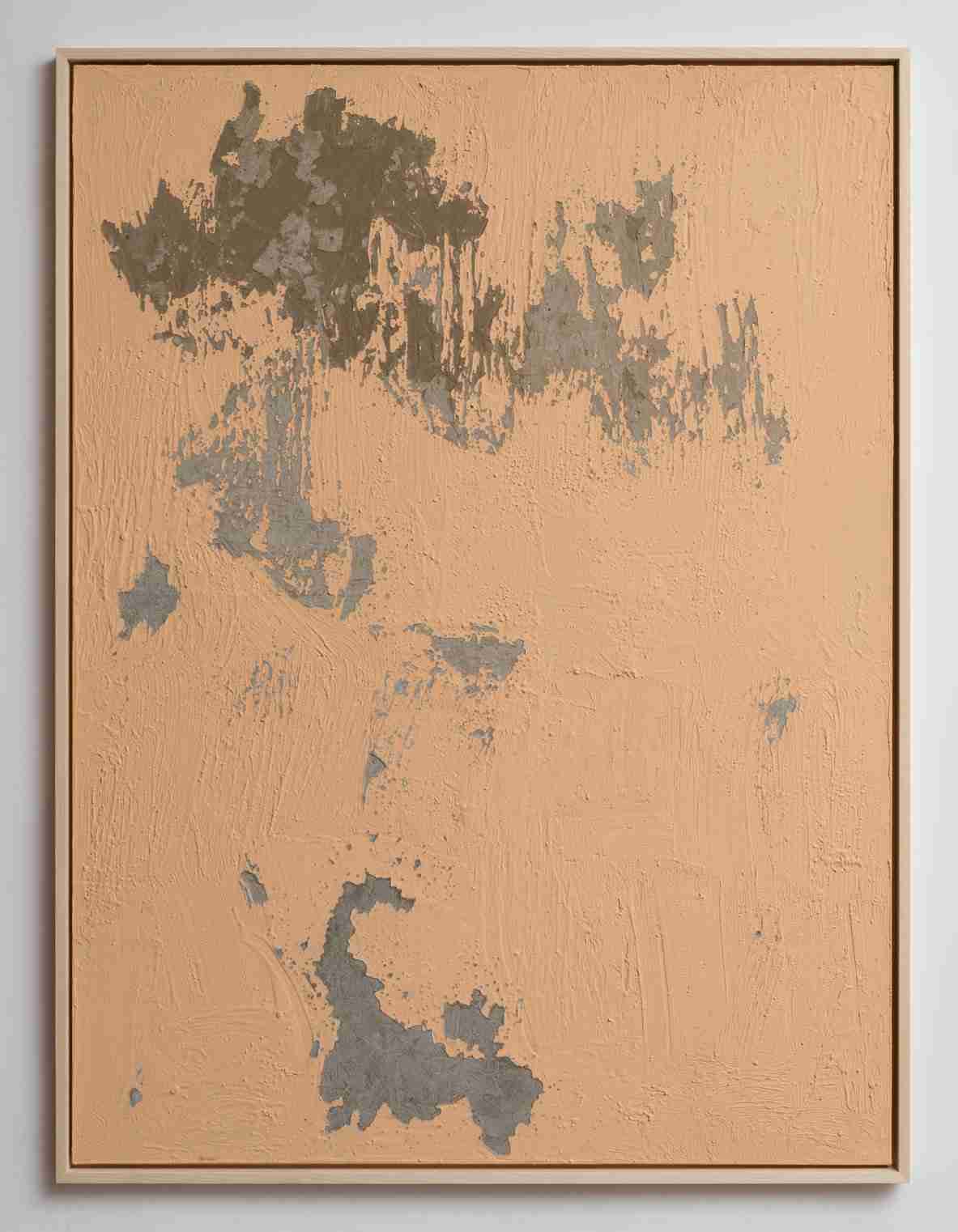

Using personal anecdotes or objects to activate our own memories and dreams, Latifa Echakhch’s work transforms life into a suspended theatre set. Born in Morocco and based between Paris and Matigny in Switzerland, Echakhch consistently shows her work internationally. She is currently working towards a solo exhibition representing Switzerland at the 2022 Venice Biennale. Having first met at La Becque artist residency in Switzerland, Haseeb Ahmed and Latifa Echakhch have continued their dialogue during the past few years, notably during Echakhch’s exhibitions in Belgium at Dvir Gallery, Brussels and BPS22, Charleroi.

[Here is our interview with the director of BPS22. Ed.]

***

To start more generally, I would love to hear what you are working on at the moment.

Latifa Echakhch: I’m mostly concentrated on the Swiss pavilion for the upcoming Venice Biennale. The core of the project is related to rhythm and temporality on which I am doing a deeper research especially in relation to memory and on how the mind edits the memory of images and objects. This was already part of my work but is being rephrased related to rhythm and musicality. It is another mechanism that I have to learn. Because I am analyzing all of these mechanisms more deeply, I also see my work very differently than before. I am learning another way of working, and therefore rediscovering my own practice. I am also preparing another installation for the Istituto Svizzero in Rome which will be visible from the outside; a theatre scene in a very romantic style. It is a development of a work I presented at Kaufmann Repetto last October. It’s a concert stage, which is a bit upside down and chaotic. When everything is closed, an installation which is visible from the outside, day or night, means that we can think of the process differently. The work has its own temporality during the several months of the exhibition. The framework for the concert is frozen in time, we don’t know if the event will happen or not. I started developing this project before the pandemic in the same way I often work – the spectator arrives after something has ended or before it has started, but we do not know what or why. I like this interstice of time, when we cannot define the where and when, or what is happening in front of us. I enjoy situating my work in this melancholy of that which is not existing in the the moment, but afterwards. It offers a lot of poetry and meaning that is not evident when we have a real event in front of us. I have been developing this kind of work for the past twenty years, but during the pandemic I feel as though now people can understand how I have felt every day since my childhood.

You speak about rhythm and temporality in this moment of suspended time that we are all experiencing. You said you have always felt this kind of way, and I wonder if you’re arriving in your native time. Do you try to use rhythm as a way of reinforcing the sense of suspension of time? Do you fear time passing and want it to stay still, or do you like the moment of potentiality before the things occur?

Latifa Echakhch: It took me a long time to understand why I feel this way. When I was a child I arrived from another country and had to adapt to a lot of cultural directions that I hadn’t learned before. Everything was strange: the objects, Christmas, Easter, all of the occidental culture, including how people interact with each other which I didn’t know previously. When you arrive in a foreign country, you see everything as though it’s vibrating and questionable, all the time. Maybe this ‘decalage’ started at that time, when I was next to things and not inside of them, like an observer. Later, my father worked at Casino Grand Cercle in Aix-les-Bains. There were restaurants, and a stage for opera, music, dance, and pop concerts. Sometimes I would attend the events, always sitting in a small box on the balcony. The theatre is strange because there are people, decor, and things that are not real – that we know are not real – but we are told a whole story in one hour, learning things about life or humanity. However, my strongest experience was after the event. Since my father worked there, I could walk on the stage after the actors and the visitors had left, which I loved. Everything that was so fantastic or marvelous from the balcony was so basic and fake. Everything that seemed magical was no longer magic, but it had that potentiality. Maybe that’s how it started. It’s not that I love drama, or sadness, it’s just that I love to imagine that anyone can change every time. The viewers of my work can always project a future action on it. I propose something that has an aura of being bigger than the object in and of itself. It’s stranger than a still life.

It’s interesting to hear how another place of potential opens up once you pass the threshold between being the observer and being on the inside, where you can change things consciously. Having gotten to know parts of your personal life in Switzerland, and then seeing your show at Dvir Gallery in Brussels, it gave me another kind of proximity in relationship to your work. The rug pieces you installed were moments of tableau from your relationship at its advent. There is a meticulous reconstruction and highlighting of certain aspects. I also tried to experience it through the eyes of someone who didn’t have the personal information I had. How do you see these different levels of engagement, inside or outside?

Latifa Echakhch: Those works were particular because they were not only about me; they were fragmented portraits about the beginning of a relationship. It was edited – there were samples of things, remixed. The objects in my work are not related to personal stories because I want to showcase them, but because it has to start from somewhere. The objects I use are very basic. You can recognize a shirt, an LP, a glass of wine, or other basic things that you can project upon. What I like about that is that when I give that to the audience they can recognize themselves in the object without my own story. For the exhibition l’Air du Temps at the Centre Pompidou I asked myself which objects I remembered from my childhood, then looked for months to find objects that were closest to those in my memory. It was nice to see that other people also remembered having these same objects – the banality makes it relatable. The moment the installation is presented to the public it is no longer part of me, but proposed to the imagination of the public.

Everyone’s stories of their own relationships are very special, but if others can relate with their own stories then perhaps one’s own memories feels threatened. However then you find a new way to connect with other people. You lose something but you gain something else.

Latifa Echakhch: Exactly. The beginning of a love story is something that sounds so exceptional, so magical, but you are in the same state of mind as thousands of others. Everything sounds exceptional but it’s not. I would love it if people recalled the first month of their love story when seeing my work. That would be a nice present for them – do you remember these magical things? The materiality of the work is not exceptional, it’s like a dry ruin of a memory. It could be seen as dramatic, but the potentiality of the moments is in the perception and not in the reality of the installation, which is just objects on a carpet tinted with black ink – it’s actually quite dry and raw.

I think it also points to the difference between the thing and the object as described in continental philosophy. What we see isn’t always the material qualities of the object, but all of the associations and the mental concept of the thing.

Latifa Echakhch: When I give a little bit of my own life to the public it is to make them think of their own lives. Artists in general do the job that people do not have time to do. Artists have practiced to develop our perception, analysis, and to create links between feelings and situations. We spend our lives on rethinking how we perceive the world and how we can give this back to people. My work can just reveal people’s own feelings. I am just a facilitator transmitter. It’s nothing extraordinary.

One thing that made an impression on me during our past conversations was when you told me that my tendency to work too much was an immigrant problem, that we have to work to prove our worth to ourselves but also to the world around us. When you’re an artist the question of what work is is ambiguous. Can you speak more about the immigrant problem and how this relates to being an artist?

Latifa Echakhch: I have actually thought about this recently. One day, when I was 27, a curator told me that as an immigrant I had to prove to myself that I was in the right place, that I had to work harder than others to prove I was legitimate in the cultural field. It is hard to feel legitimate in one’s position as an artist. Now, because I am teaching again, I am trying to understand how my students work, and I see the same thing in some of them. I understand now that this immigrant problem is not the fact reason that we work more, but I think that we never feel legitimate in our place. We feel like we have to work do more than others. We have something in the back of our mind saying that we need to work more to prove that we are in the right place. If you don’t have this question any more, you know you are in the right position, and if you work a lot it is because the work demands it.

That’s an interesting nuance because it recognizes conventions and then measures your work against them. I wonder if there is a freedom in addressing or dealing with these kind of cultural conventions when you are able to recognize them.

Latifa Echakhch: I don’t like the word “normalized”, but the more that it is normalized the more legitimate we will feel. I always try to make an effort to speak French perfectly, because I know that when people see me they do not see a French woman. The first exhibition I did in Paris, a woman looked at me told me that she was surprised I spoke French so well. It was a double-edged sword. If nobody cared about it, it would be much easier for everybody. But to change this, we have to start with our own perception.

I recently saw that you joined the board of the Swiss Institute in New York. Do you see this as a place for normalization the place of immigrants or is it unrelated? How do you see your role on this board as an artist, beyond the biographical questions of being an immigrant etc.?

Latifa Echakhch: I am a woman, I am an immigrant, and this comes into play. But I have also known Simon Castets, the director, for many years. I was always aware of what he was instating and changing, because we had so many conversations about how an institution can not only help artists but also question our society. When an opportunity came up for another artist to be part of the board he chose me, allowing us to go deeper into our previous conversations. I now know the programme and internal functioning by heart and I am very much part of it. Some artists don’t like to be involved in political groups or institutions, boards, or even teaching, but for me it’s one possibility I have to help our community. I think it’s a good tool, and I am comfortable about discussions concerning politics, funding, meetings and trajectories.

Just as a caveat, I didn’t mean to imply that your appointment was related to your ethnicity or gender.

Latifa Echakhch: But we do think about that. When my name is in an institution people know I’m from Morocco, and there are always immigrants who show up during the opening. Maybe some kids will think ‘wow, that’s cool, I can do that too’. When I was a kid there were almost no immigrant artists in the scene, and it’s true that these things are important. Now you see many Arabic artists from immigrant backgrounds, but before there was hardly anybody.

It is definitely encouraging. That answers the question of the place of an artist on a board – envisioning trajectories and being a sounding board.

Latifa Echakhch: Boards are built for sharing information and points of view. People from different backgrounds give a different understanding of things, raising awareness for all of the questions we now have in society. I also learn a lot from people in high spheres of collecting or finance. In a way, my career started was helped by at the Swiss Institute in 2009. They welcomed me as an artist, they gave me carte blanche, and being on the board is a way of giving back to them. They will do the same for a new generation of international artists as they did for me.

It’s interesting to recognize the art world as a community, constituted of very different types of people from different backgrounds, from all over the world. In a way it’s a utopian community, built on ideals about the importance of art in society. It’s also rather tenuous because it’s hard to grasp and is self-selecting, which is unlike other communities.

Latifa Echakhch: I am lucky to be at the point where I can show my work, share my work, and live from it. I thought that it would be impossible. I remember realizing my work was really not desirable. It’s not fun, it’s not sexy or sensual, and I thought that I would never sell anything, that nobody would be interested, because it’s too serious or dense or has too much gravity. It was ok with me that it would just be my path. The only thing that changed when I became well known was the possibilities it gave me to develop my work. I could never produce and share a piece for 10,000 viewers on my own. You just have to choose to be sincere with your practice, as success can be fickle. If you have a practice that nobody buys, it is what it is. You cannot find yourself another style – artists are not producers. We just see things and translate them.

That’s also what I try to emphasize to my students. Be happy with your work and hopefully everything else will fall in place.

Latifa Echakhch: An artist can also point out details of the world around us. Last week I was in the mountains in Switzerland, and there was a lot of wind. I started to think about the wind, and then I thought about you, and remembered that the wind comes from much farther than we think. You pointed out to me that the way I perceive things could go further. Since you did the work, I can just remember it. This is precious.

Thank you. I think a lot of artworks work as an after-image; you recognize the perceptual shift that they’ve caused afterwards. This brings up another question, because I know you’ve started to collect artwork. When you speak about the value that you can create as an artist, and the role of creating objects the consequences of that, I was wondering if you could speak about artworks that interest you, or something that you may have acquired.

Latifa Echakhch: When I was a kid I collected little pigs, then later I collected books, even if I had to save money to buy them. When I started to have kids and more means, I started my collection. I was aware of the importance of the first work, and I looked for a photograph by Jean-Luc Moulène, because I remembered seeing it when I was in Paris the first time. I’m not very rich, but when I earn some money, I keep a percentage to buy another artwork. The work I have is by artists who are important to me in a way. There are a lot of important works that I cannot acquire, such as works by Bruce Naumann or David Hammons. I have a work by Bas Jan Ader, a study in the research of new plasticism, and when I see it it is so beautiful and absurd. I really love it. I know all about his work, but I don’t know what my daughters’ think when they see it. I also have photos by Wolfgang Tillmans. When I was younger I hated his work – it was so fashionable and trendy, and slowly I kept seeing his work and I really started to get it. Every time I leave one of his exhibitions, I come back to my real life and I feel like I am reframing everything according to his way of composition. That is extremely powerful. I also have historical things like Meret Oppenheim and Francis Picabia, or Romanian avant-garde like an engraved wax by Victor Brauner. I did a work in 2006 about the Jewish avant-garde in Romania; they were not considered Romanian and moved elsewhere, to France in particular. I created a work from Romanian avant-garde magazines between the 20s and 40s, engraving on a linoleum floor. When I found the engraving by Brauner I liked how having this work in my home closed this loop. I also support younger artists like Mohamed Bourouissa, Petrit Halilaj, Simon Fujiwara, Adrien Chevalley, Naama Tsabar… The things I love that constitute my landscape are very vast, like my music collection. I have no work of my own hanging, I like to show my interests and the things I love to my friends, my guests, and of course my children.

I also want to approach your exhibition for the Venice Biennial and the idea that this is kind of a penultimate exhibition for an artist. Do you approach differently than how you would approach any other exhibition?

Latifa Echakhch: I approached it in a very different way. Rather than thinking about what I will do, I thought about how people will feel after the exhibition. Music and temporality are central, but there will be no sound – but it is about the mechanism, not the effect. Everything started with a conversation I had with Alexandre Babel about how he starts a project. Does he write before he plays? How does he plan sound? When I was invited to propose a project for the Swiss pavilion I wanted to work with someone who works in a completely different way than me. We work with different tools, and our perception of time is a little bit different. But the repetitions, the variations, the alterations of notes, the questions of harmony and dissonance are the same. I started to listen to music in a different way. After that conversation I started to project myself as a musician, understanding a piece of sound like a landscape. It’s opened up a new world for me, like learning another language, but much deeper. Then I started to practice music by myself; I started learning piano again, reading music, and singing. With the piano, notes are exact. With your voice it has to be direct. This means that you cannot overthink, or it will be forced. It’s something that has to be felt, but everything is more flexible and fluid. Mathematics play a part, but when you practice, it has to be direct. It’s like my sculptural practice – if i think about it too much, I will make mistakes.

February 2, 2022