Estrid Lutz and rootless cyberpunks today

Estrid Lutz’s dislike for finishedness, common beauty and constrains makes her a kin to previous renovators of punk attitudes (and surfers)

How does an artist reference well? How does he/she soak a historical source in but later avoids squeezing it out into tedious imitation work? Operating within a framework of rather precise references, even if unconsciously, always poses the challenge of maintaining an ever-wanted freshness in one’s art practice. Estrid Lutz excels at that. She is situated without being a follower.

Born in the late 80s, Estrid Lutz is the distant daughter of traditions and aesthetics she could not possibly remember from her childhood years. During our conversation, she mentioned the “metaverse” multiple times, a concept described as the sum of all the virtual worlds interacting with the physical world. Coined before the internet era in the American science fiction novel Snow Crash by Neal Stephenson from 1992, the metaverse has been now updated to include the developments of technology until today. Despite how prosthetic the web has become in our lives, it does remain a world besides our physical one, hence belonging to the metaverse.

It might seem odd that someone who is into metaversal scapes, and indeed at ease with them, physically lives in a fairly remote corner of the world. A couple of years back, Lutz moved to Puerto Escondido in Mexico, one of surfer’s havens where, according to the artist, the biggest concerns are the size of waves and making enough cash to guarantee a daily dose of fish and tacos. For Lutz, the art system of cities felt too unfree and boring to fuel her need for adrenaline and stimulation. Being away did.

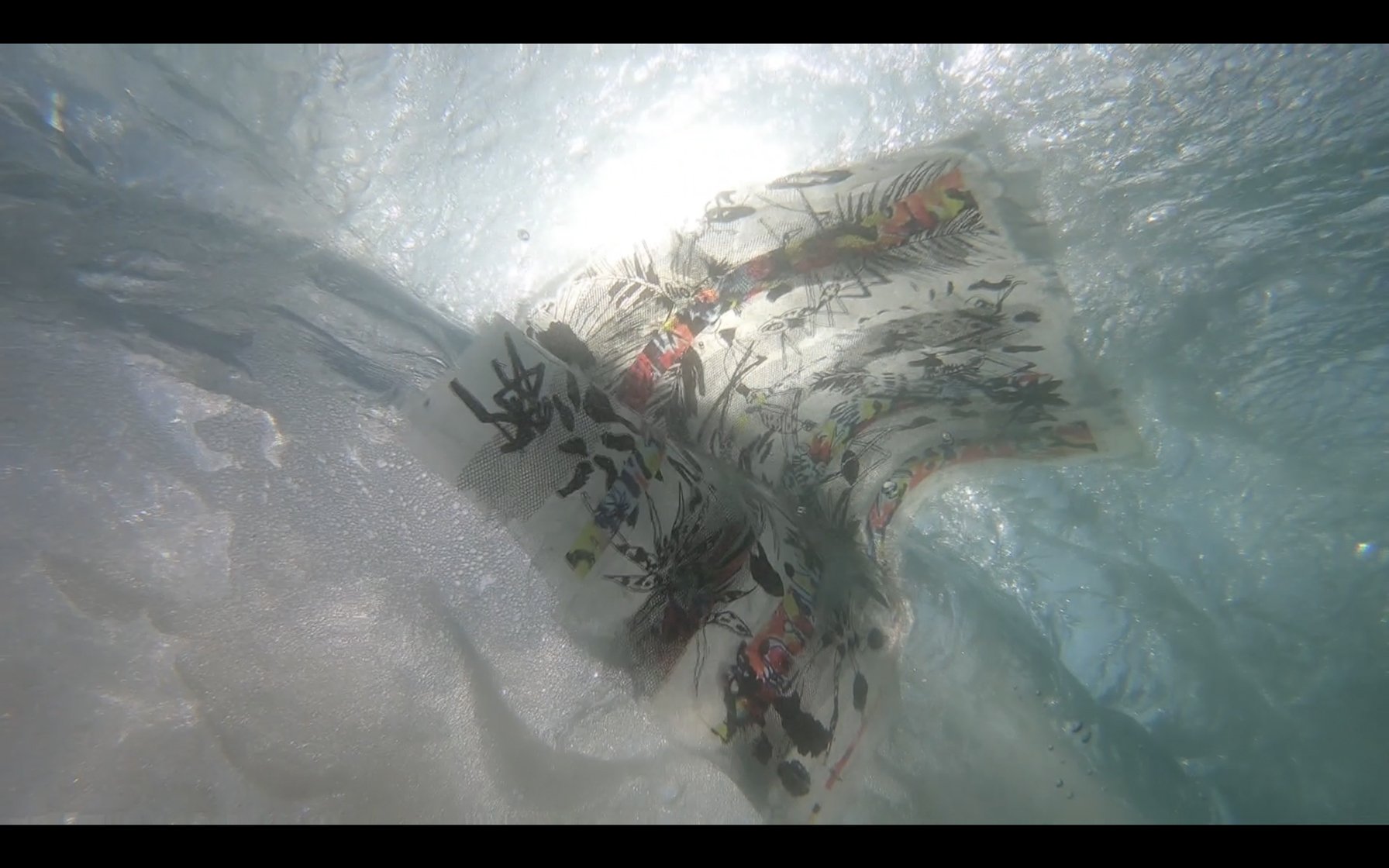

At the same time, the Mexican beach turned out to be rather disconnected from her artistic experiments too. She confirmed to us that nobody in Puerto Escondido really understood why you would ride some waves in order to plunge artworks into the water, or why you would fly over the ocean just to drop flowers in it from the sky. We speculate this kind of lifestyle discomfort is pleasing for Lutz, along with self-posed risks like racing in fast cars or swimming with sharks and crocodiles—two of the artist’s pastimes. Indeed, her approach to art is to create something surprising, first to herself: a sort of artistic extremism.

In the age of forced confinements, and most likely even earlier, remote places surely don’t equate with solitude. Contemporary connectivity no matter where you are is the core concept of hospitality services offering the best of both worlds: economic opportunities typical of cities delivered to your laptop, which you open only between surfing sessions in exotic destinations. As an artist, you can check your Instagram multiple hours a day to keep track of the latest art system’s news and gossip without having to attend any of the way-too-coded art world’s events in person. The metaverse is right by the ocean if you look for it.

You might wonder how Estrid Lutz’s artwork visually translates this attitude. We come back here to the idea of avoiding literal referencing. In a nutshell, the artist subtly sidesteps cyberpunk, itself the 10 year older precursor of the concept of metaverse. The two ideas share the blending of virtual and real, but cyberpunk comes with a type of behavior too, an added inclination, an etiquette for the liminal spaces. Lutz strives over there. Her work, whether collage, painting, or more sculptural one, behaves like she does. Away from the historical understanding of the concept, her need for adrenaline and freedom is somewhat “punk,” and so are her artworks.

They both dislike obsessive precision, finishdness, common beauty and preciousness. Moreover, if the 80s and 90s cyberpunks and metaversians were actually rather sleek in their aesthetics—polished steel prosthetics and beautifully crafted machines were a must—Lutz instead enjoys the debris and cracked leftovers of hyper technological materials like those used for spacecrafts or Internet infrastructure.

Her stuff is broken and volatile, like that in the works of earlier artists who adopted and renovated punk attitudes in the late 90s and early 2000s. Think of Steven Parrino and Banks Violette for example, more extreme artists than Lutz to some extent, visually interpreting attitudes differently, yet comparable in their love for adrenaline and intensity. It is no surprise that, like Parrino and Violette, Lutz is also a musician—an early punk drummer to be precise.

[For a reflection on Steven Parrino, check this chat between artists Francesco Joao and Sven Sachsalber. Ed.]

Twenty years have passed. Unlike these artists, Lutz lives in an era where artistic expressions are more accessible thanks to technology, hence she comes across as a more eclectic listener, much less linked to a precise genre or music community as the heavy metal goth of Violette for example. The playlist she shared with us took us from the extreme gabber caricature of Otto Von Schirach to mellow and synthetic Vaporwave voices, passing by the electronic vibes of James Holden and the experimental rock of Xiu Xiu.

On the other hand, Lutz embodies what comes after the post-internet generation of 5-6 years ago [here is the link to our writing about this artistic movement. Ed] . She mentioned she is personally close to Katja Novitskova, one of that generation’s representatives [here is the link to our interview with the artist. Ed]. What breaks the two apart is a few years and coming-of-age after the experience of a pandemic induced home-confinement, where people finally shifted their attention away from the emerging symbols and aesthetics of the by-then-established web. All of that is missing in Lutz’s work, which has surely come to terms with the web’s old novelties. Moreover, the corporate culture present in much post-internet art—coincidentally one of the characteristics of early 90s cyberpunk too—is also missing in much of Lutz’s art.

Estrid Lutz has recently been an artist in residency at CIRVA in Marseille, a place for experimentation with glass artwork production. She told us she loved that experience despite an initial, apparent incompatibility between her approach to art-making and a precious and finished material such as glass. Lutz works fast and instinctively: how could she fit the slow process of shaping glass, with its long pauses and multiple stages? Future will tell, as she hasn’t shared any finished piece from that production yet, despite confessing how pleasantly surprised she was about the results.

[Here is our list of top art fabricators, which includes CIRVA Marseille. Ed.]

It would be naive to believe that each artist has his/her own specific concerns. Those are shared within communities, generations, groups, etc. The way to go about these concerns, their representation and expression through art, might be individual though. Estrid Lutz’s concerns and desires might belong to others too, yet her actualization of them is just hers.

November 19, 2021