At the show with artist: Elena Ricci encounters Frans Masereel

Frans Masereel presents us with an intensely personal vision of life. It is a vision which shows an understanding of each aspect of humanity, in which both the highest and lowest levels form part of a whole.

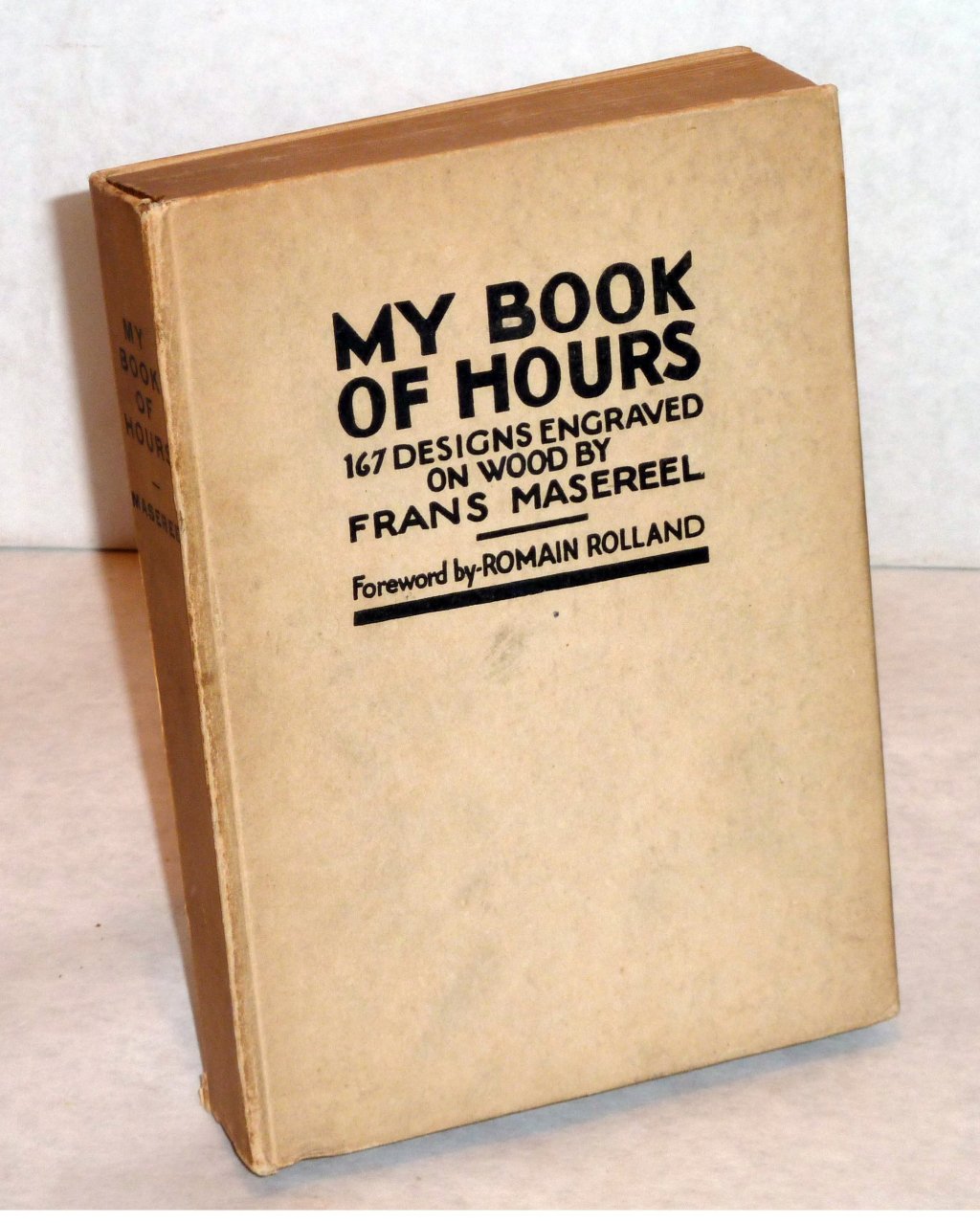

Some time ago, I was browsing the shelves of a bookshop when I happened to come across a small book with a beautiful woodcut on its cover. It was Frans Masereel’s My Book of Hours, an unexpected guest among the other covers. Although captivating covers can often lead to disappointment rather than discoveries, as I opened the book this time, I entered a visionary and realistic world. It was a world of irony and poetry, made up of beauty and ugliness, containing the highest and lowest impulses. I realised that I had come across something beautiful from both an artistic and human standpoint.

But who was Frans Masereel? Despite my passion for woodcuts from this period, for some strange reason I had never seen his work before. Frans Masereel was a Flemish painter and illustrator born in Blankenberge in 1889. His vast oeuvre mainly consists of woodcuts. He illustrated books by Zweig, Rolland, Whitman and Rilke, and he collaborated with pacifist newspapers and magazines. Above all, after the First World War, he invented wordless novels: books made up only of black and white images in sequence, without any words other than the title. These books were not only predecessors of the graphic novel, they also referenced cartoon films and silent cinema.

Between 1918 and 1925, Masereel published five wordless novels, all in his favourite medium of woodcutting, which makes the images contrasting, primitive and essential; a medium suited to representing the crudest aspects of the human condition.

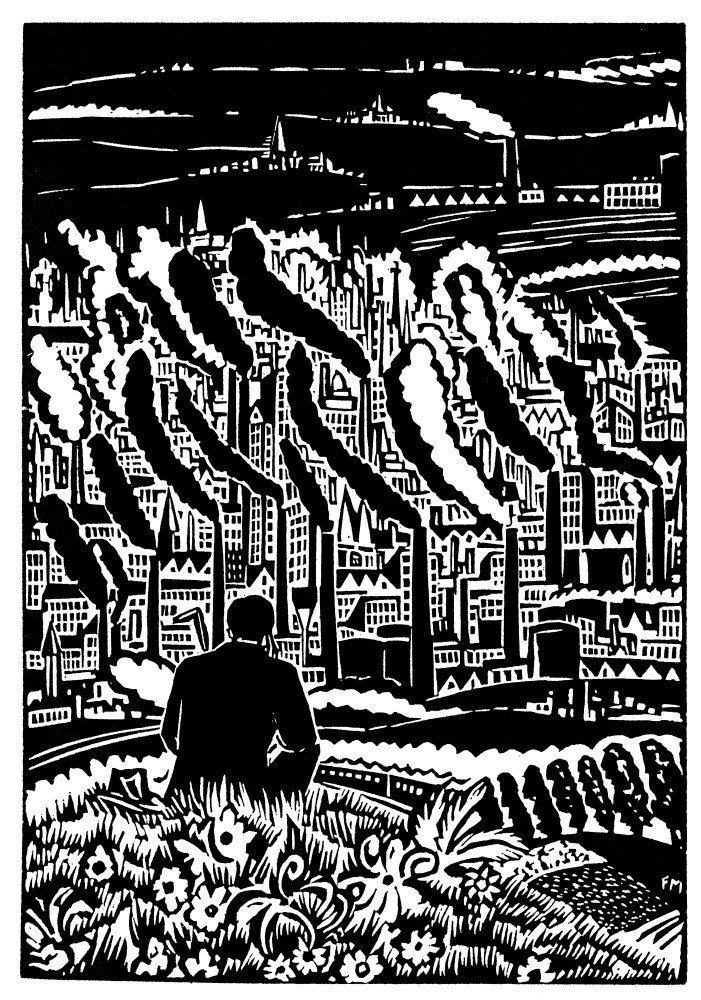

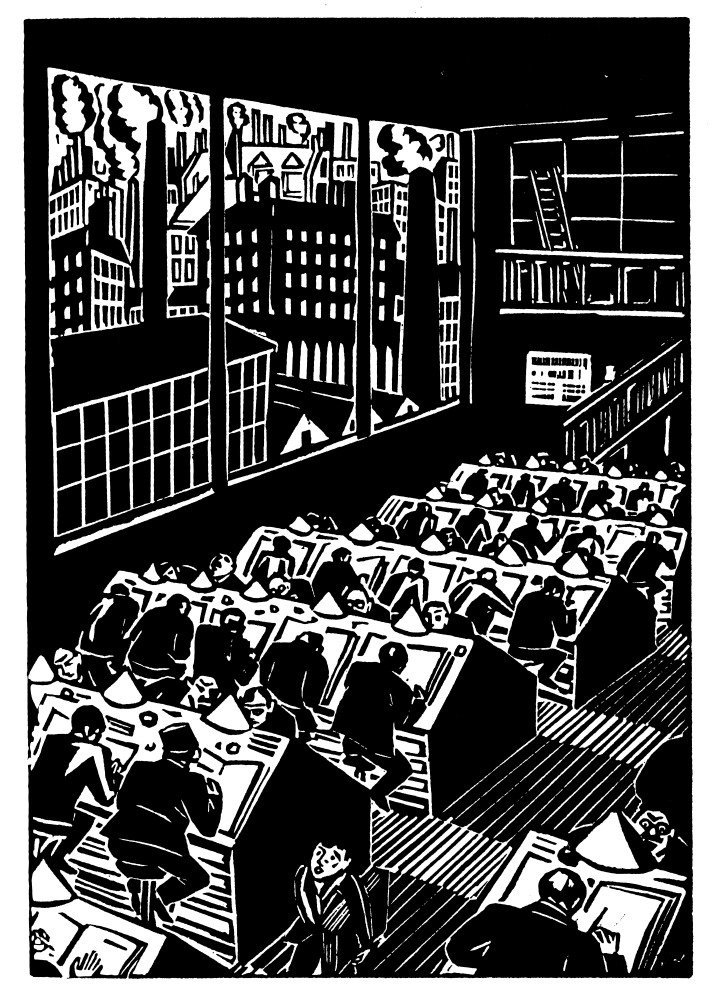

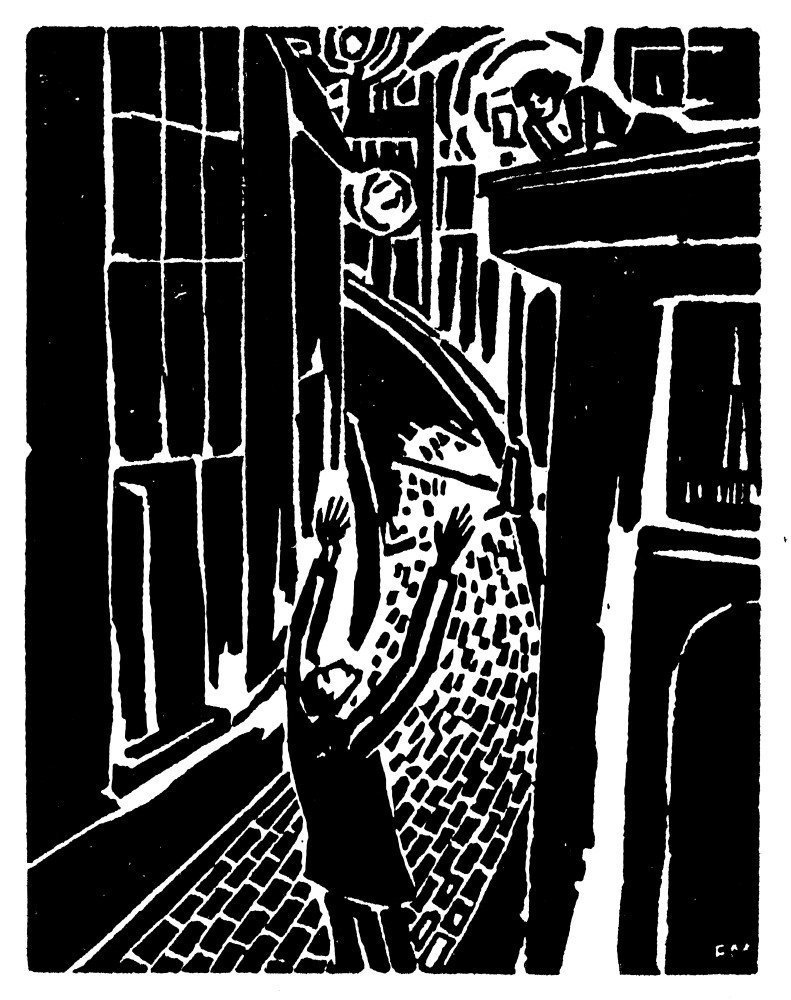

From Frans Masereel, The City, 1922.

From Frans Masereel, The City, 1922.

From Frans Masereel, The City, 1922.

From Frans Masereel, The City, 1922.

From Frans Masereel, The City, 1922.

From Frans Masereel, The City, 1922.

From Frans Masereel, The City, 1922.

‘Selling a painting is fine’, explained Masereel, ‘but then it disappears into a collection or the private sphere and it is all over: a kind of first-class burial. I chose woodcutting because it allows me to reach far more people.’ Masereel had a popular objective. His wordless novels were able to spread a pacifist and libertarian message to people of any social class. But his vision – beyond being ideological and political – strikes me as being more characterised by a profound humanity.

The title My Book of Hours harks back to the miniatures in old prayer manuscripts which defined the era of their owners. In Masereel’s book, we see the protagonist – a young and naïve man – arrive in a city teeming with people. There he embarks on a whole range of adventures, as he wildly races to find something. We see him lost in a crowd, among the buildings and fumes of a modern city; we see him happy between the legs of a prostitute; dancing and singing; helping someone; haranguing the crowd; playing with children; taunting priests and the bourgeoisie; surrendering to sadness; praying; urinating among the city roofs; loving. He is a wandering figure who never seems to find his place and who – even among people – always remains alone. Towards the end, we see him roaming through a wood and merging with nature and the cosmos, as his carnal and spiritual journey through the world comes to an end (although not without indulging in a final mockery).

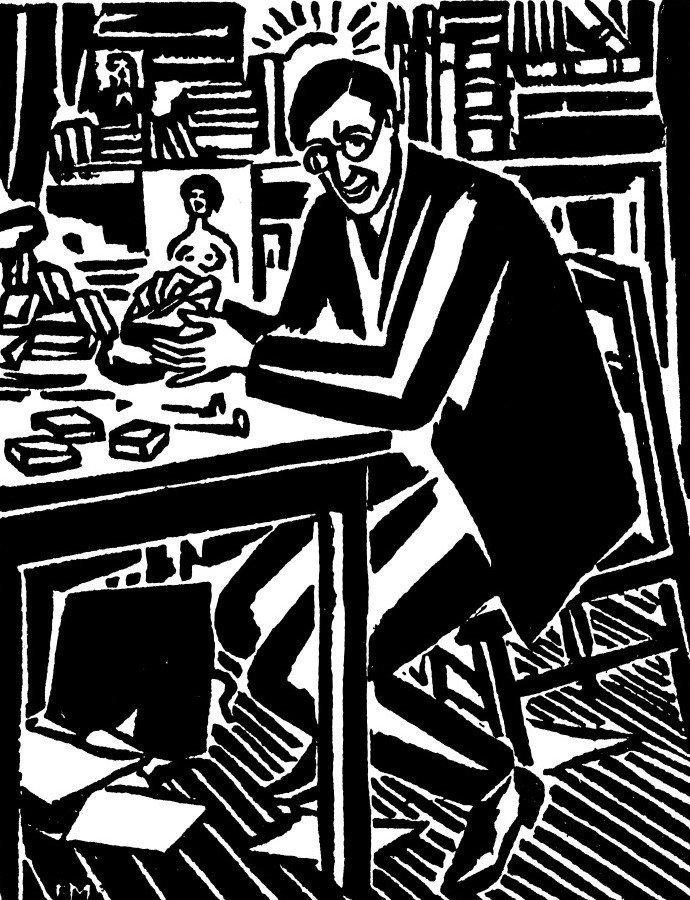

From Frans Masereel, My Book of Hours, 1919 (English edition, 1922).

From Frans Masereel, My Book of Hours, 1919 (English edition, 1922).

From Frans Masereel, My Book of Hours, 1919 (English edition, 1922).

From Frans Masereel, My Book of Hours, 1919 (English edition, 1922).

[Here is the link to the Maseerle Group website, were Frans Masereel’s main works are available in digital version. The artist’s books are no longer protected by copyright in the United States. Here is the link to Fans Masereel Centrum, a dynamic contemporary art center and residence for artists and curators, named after the Belgian master. Ed]

Frans Masereel presents us with an intensely personal vision of life. It is a vision which shows an understanding of each aspect of humanity, in which both the highest and lowest levels form part of a whole. His protagonist – the artist’s projection – looks at the world with innocent eyes, sometimes observing it from a distance, and sometimes letting himself be overwhelmed by its events. Some people mock him, others love and admire him. Masereel’s gaze and work are an unconditional embrace of humanity in all of its greatness and in all of its pettiness.

—

Note: Elena Ricci was born in Rome in 1973, lives and works in Milan. She trained in Paris at the Ecole Nationale Supèrieure d’Arts Paris-Cergy, where she studied painting and drawing. Her artistic practice explores the realms of psychology, anthropology, mythology and religions.

September 20, 2021