Hair air style from Middle Age to Botticelli

Hair colour had a moral significance, the hairstyle a message of seduction or betrayal. And each hair became a story

The twentieth century was the era of platinum blondes, epitomised by the cult of Marilyn Monroe, and in large part thanks to cinema and the famous novel by Anita Loos, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. Yet the moral and aesthetics associations of hair colour have had a long history over the centuries, in cultural practices, literature and visual iconographies. When sixteenth-century Italian poet Torquato Tasso wrote in one of his love sonnets ‘Dark-haired lady, you are still beautiful’, he then warns that we must be wary of redheads. In frescoes painted around 1200 in the convent of Saint John, in Mustair, Salome is depicted shamelessly displaying her vivid, almost devilishly red hair, which drapes down her back, in contrast to her mother Herodias’s veiled, tied up hair. Among the dancing, Salome’s hair hangs loosely and yet remains close to her neck. In comparison to the demonic associations with red hair, during the Middle Ages blonde hair represented purity and the spiritual, heavenly elevation of love.

‘She let her gold hair scatter in the breeze…’ With this enchanted line, Petrarch outlines the imagined figure of his beloved Laura. Her golden hair comes loose in the wind, transforming her into an angelic figure. King Mark of Cornwall gives Tristan a piece of blonde hair in order to help him track down the woman to whom it belonged, that is, his future wife: ‘she was called Iseult the Fair because she such blonde hair that it seemed only to be made of the finest gold’. Chrétien de Troyes’ Erec and Enide, completed around 1170, tells of Enide’s arrival at Arthur’s court; since she was so poorly dressed, she was entrusted to Queen Guinevere, whose maids ‘wove a gold thread in amongst her golden hair, but her locks were more radiant than the thread of gold, fine though it was.’ Unsurprisingly, Guinevere herself was blonde, and the hair she left entangled in a comb shined so brightly that ‘gold a hundred thousand times refined, and melted down as many times, would be darker than is night compared with the brightest summer day we have had this year, if one were to see the gold and set it beside this hair’. It was through hair colour, then, that judgements were both anticipated and established; generally positive for blonde and negative for dark brown or red (and mousey brown was too normal to merit any particular interest). Here is why knights and courtly poets were so excited by the blonde hair of damsels and maids, about which they sung praises and declared their affection.

Évrard d’Espinques was a miniaturist active in the second half of the fifteenth century. In the Roman de Tristan, he illustrates Iseult’s journey to Cornwall, where her future husband, King Mark, awaits. This is the climax of the love story between Tristan and Iseult. As the slender boat ploughs through biting waves, Tristan is overcome with love and, betraying his own king, gives in to a night of love with Iseult. Afterwards, however, Tristan is consumed by melancholic sadness, which soon becomes a madness that consumes his everyday life: having known true happiness, he can never again reach such a peak. In fact, later in the story, when King Mark discovers Tristan and Iseult sleeping next to each other, the sovereign realises that, to his amazement, there is a sword between the naked bodies of the two lovers (a symbol of chastity which represents an unsurpassable boundary between the two).

The miniaturist depicts Iseult according to all of the beauty standards of the age, with shaved forehead and eyebrows. Medieval hair removal was extremely dangerous, since quicklime and arsenic sulphide was used, and made the forehead appear swollen and broader. Scrubs to get smooth skin contained pieces of glass and wood; onion rubs were used to remove imperfections left by boils; and the urine of children was used to clean teeth. Hair needed to be very light, and was either bleached or false hair was used (extensions were made from the hair of blonde page boys). During the feudal era, it was acceptable for hair – previously always kept under a cap – to be left loose, or gathered up on top of tiaras, crowns or cone-shaped headdresses. Here, the gold of the crown shines through the gold of Iseult’s hair. These procedures of feminine aesthetics all produced a wave of love effects, as described in verses by troubadour poets; those who were tied to the loyalties of love (in which Dante can be included) and those tormented by the furies of poetic love. All of these feelings were at their most powerful when outside of marital contexts.

Entwined in the knots of love, Iseult and Tristan are wrapped in the golden, passionate aura of a fifteenth-century miniature. Their two faces, side by side, form an infinite image; one showing the passion of a sad and all-consuming love. Their love is like a climbing plant that grows around an ever-changing stem; but be careful, for the stem has been cut at its base. In 1900, in a re-writing of the legend of Tristan and Iseult in medieval texts, Joseph Bédier writes that from the lovers’ graves, buried close together, two plants started growing with continuously enlaced stems. Every time that the plant around Tristan’s grave was cut, a new stem immediately emerged and, once again, wrapped itself around the other, in a renewal of tragic eternal love. Of course, it is well-known that love without adversity is not material for a novel.

Cupid’s arrow shoots into Petrarch’s heart. The blind god of Love shocks Petrarch by the springs of the Sorgue river: ‘Clear, sweet fresh water / where she, the only one who seemed / woman to me, rested her beautiful limbs’. In a miniature by an unknown illustrator, included in a fifteenth-century edition of Petrarch’s Canzoniere, the heartsick poet is depicted on his knees in front of Laura who, like Iseult, is a married woman. Petrarch’s love for her will be one of spiritual, painful, distressing and total struggle. Everything shines in Laura. Her white brocade dress, embroidered with golden flowers, is reflected in the yellow of her hair, and even the light botanical wefts of thread in the subtle green background, in line with delicate Gothic decoration, seem to give out pure light. Laura is depicted crowning Petrarch as ‘poet laureate’: it is 8th April 1341, the first coronation of a poet with a laurel wreath, a tradition revived from Roman culture. Indeed, even the name Laura emblematically recalls the laurel of a bay tree. This plant and crown form the centre of the miniature, almost as if dividing it into a diptych. It echoes the Annunciations by Fra Angelico where Gabriel and the Madonna are separated by a column, no longer seen in an idealised landscape, but rather within perfect classical architecture that invites the birth of perspective.

[Read our analysis of perspective as a metaphor during the Renaissance here]

Everything in the Annunciation by Fra Angelico in the Prado Museum, Madrid, pulses with light. The dove-ray of light streaming from God into Mary’s breast; the melancholic gaze of a foreboding pain; the blonde locks of hair that have an even more intense, warmer colour than the studded golden halo… Everything is wrapped in a unifying light. The archangel Gabriel’s golden curls round off at the nape of his (hardly gilded) neck, as if forming a heavenly tonsure. The gold and blue marble tiles, which almost appear as unintentional stains, reflect the light emanating from Mary and the Archangel. In Fra Angelico’s Annunciation of Cortona, painted between 1433-1434, Mary’s braided hair is the colour of ripened wheat. These Annunciations bring up feelings of astonishment: all of this blonde-gold-light leaves viewers astonished (from the Latin ad-tonare, to thunder), as if shaken by thunder. After all, the blonde Christian beauty is anything but calming and serene.

All medieval symbolism starts from above, and moves down to below. Love for a woman is founded on loyalty towards her not as a human being, but as a higher Being. Humility, devotion, respect and loyalty are all found in Dante, and his verses for Beatrice become increasingly passionate as she progresses up the hierarchy of mystical abstractions (starting with Philosophy, then Science and ending finally with Theology). However, Dante never refers to the colour of Beatrice’s hair, and it is always implied that her hair is veiled. One could easily assume that she was not blonde, but in miniatures Dante’s muse and heavenly guide is always depicted with blond hair, according to the canons of Dolce Stil Novo and angelic imagery.

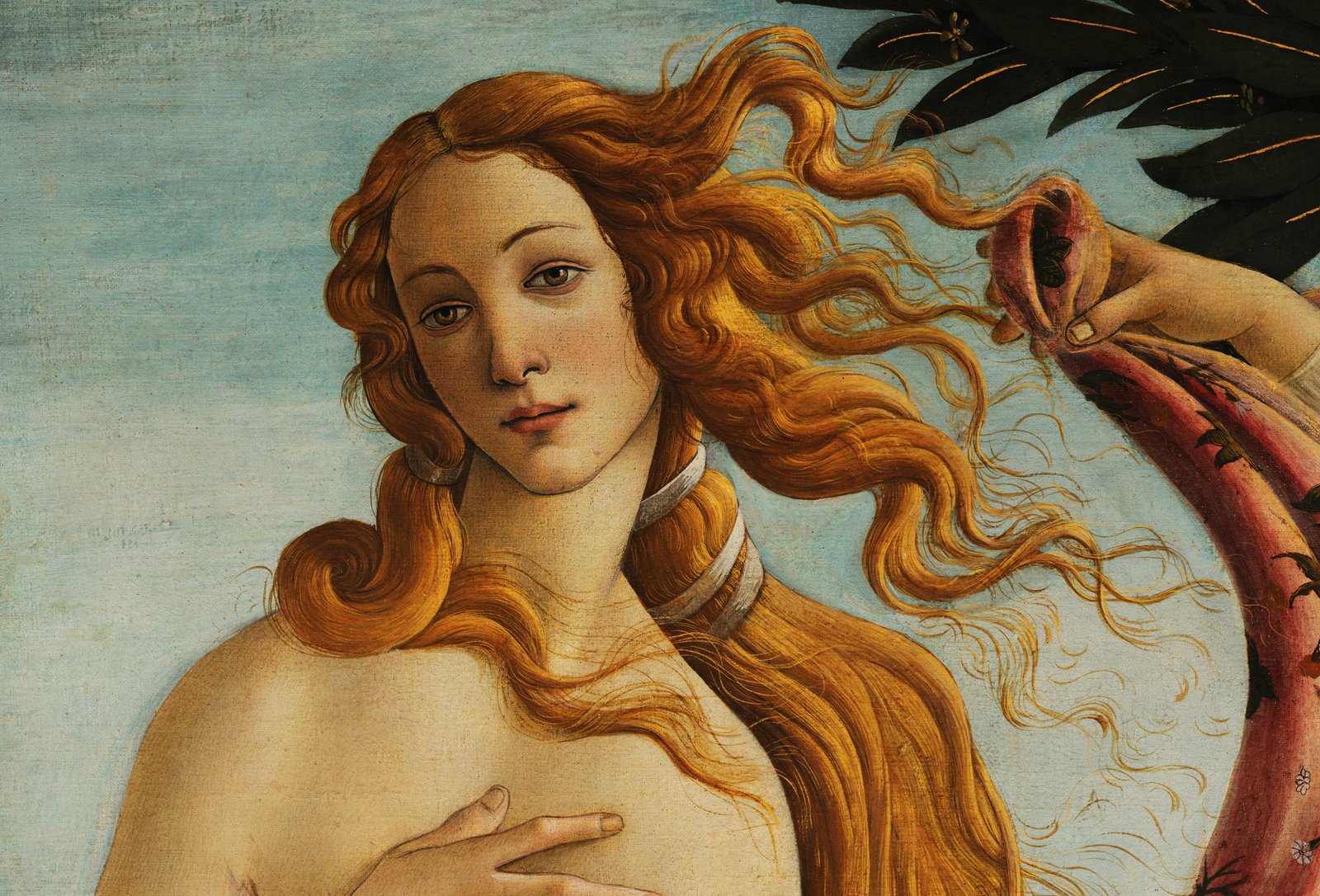

Sandro Botticelli is the master of blonde hair flowing in a soft breeze. In both Spring and the Birth of Venus, Zephyr is depicted letting out a gentle breath. The latter painting is a fine example, in which the Goddess gracefully, and with infinite modesty, uses a lock of her long blonde hair to cover her pubis. But an equally refined gracefulness is found in the blonde-haired Judith of The Return of Judith to Bethulia (painted around 1470). She takes advantage of Holofernes’ drunkenness – during which he is charmed by her body – to ruthlessly behead the Persian General of Nebuchadnezzar. In the depiction by Botticelli (also assisted by Filippino Lippi), Judith walks as daintily as a goddess, and her face turns in the same way as that of Botticelli’s Venus. However, the scene can hardly be called discrete. In one hand Judith holds a sharp longsword and in the other an olive branch; the head of her enemy is carried by a maidservant, who balances the basket on her head as if it were a water urn. Blondeness may here be associated with Eros and blood, but Judith’s cruelty is used to punish political and carnal ‘heresies’. And, after all, she was on a mission for God.

[Read our analysis on Botticelli’s portraits here]

‘Up to the fourteenth century, fairly simple hairstyles prevailed, with hair being wrapped around or gathered on the head, or plaited in braids. Hair was held up and adorned with bands of fabric, ribbons, wreaths, coronets of precious metal, decorative threads and jewels,’ Virtus Zallot points out in her Medieval Heads, a book that collects poetic quotes about hair in medieval literature. Zallot highlights that during the Renaissance, sumptuary laws were used to limit assets of pearls and precious stones used to accessorise hair; luxuries that were only permitted for the aristocracy. One must only think of the lavish hairstyle of Battista Sforza, depicted opposite her husband, the Duke of Urbino, in a diptych by Piero della Francesca; her hair is tied with high-value ribbons in a bow at the side of her head. Enhanced by the shaving of eyebrows, her forehead would have been highly fashionable, made even more so by the inclusion of pearls and precious stones (which are made vividly bright by Piero’s use of oil glazes, in line with Flemish techniques).

[Read our analysis of Gian Giacomo Poldi Pezzoli and his museum here]

In Portrait of a Girl by Antonio or Piero del Pollaiuolo, painted around 1470 (and symbol of the Poldi Pezzoli Museum in Milan), and in Portrait of a Young Woman painted in 1465 and attributed to Piero del Pollaiuolo, the two noblewomen are presented in profile; since their full dress is not visible, this composition presents their extravagance through hairstyles. Veils, ribbons, headbands, pearls and, above all, hair so light that it appears to be bleached, all indicate that their hair was styled by an expert ‘hair stylist’ of the period. Embellishments are varied, cumbersome and sometimes bizarre; clearly, when it came to hair, artifice trumped nature. All of this work on the appearance of ‘headwear’ was used to intensify feminine attributes. On the other hand, however, as highlighted with some irony by art historian Daniel Arasse, if men boast attributes of virility (and we know what they are), there is not an equivalent term to reference virility for the feminine. Therefore, hair is surely one of the attributes of femininity; it is not a coincidence that, until the turn of the twentieth century, a lock of hair was given as a gift to a lover.

The suggestiveness of hair (and the feminine implications it gave off) also made it a tool for punishment and martyrdom. In the Civic Art Gallery in Foligno, there is a torn fresco by Bartolomeo di Tommaso, depicting the martyrdom of Saint Barbara, painted in 1432. The scene is almost like a cartoon, reminiscent of the Fred Flintstone’s crass catch-phrase: ‘Wilma, give me my club!’ Her long blonde hair, already the emblem of Christian holiness, is pulled by her father, Dioscorus; indeed, it is father/master who eventually beheads her. Even more surprising is the Martyrdom of Saint Agatha by Giovanni and Battista Baschenis, painted in 1488 and kept in a small church in the Val di Sole in Trentino. In the scene, the saint is tied to a cross-shaped structure by her long blonde hair, with her face framed by a glowing halo, whilst two torturers dressed as lansquenets tear her breasts with pincers.

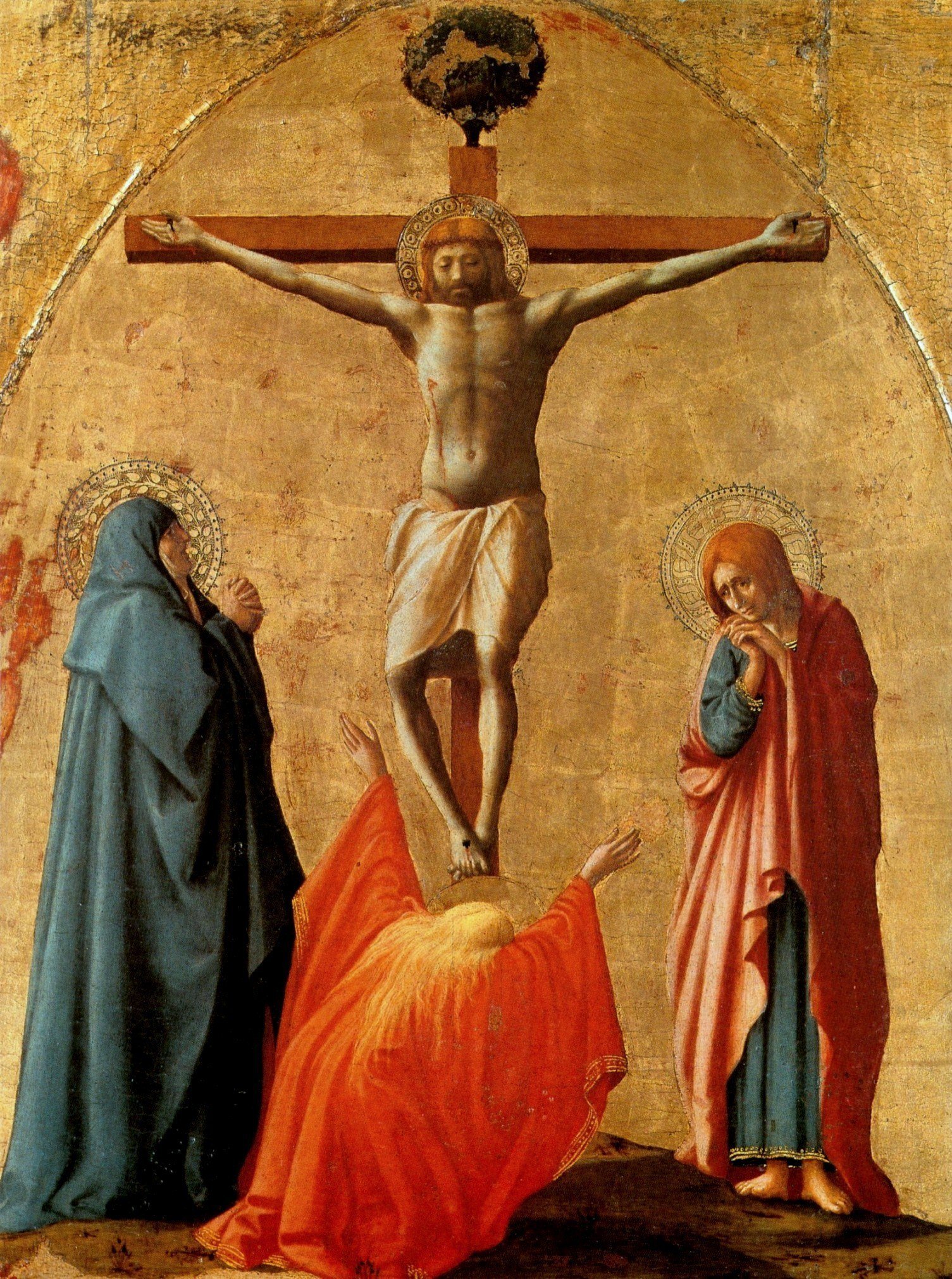

Mary Magdalene is surely the most famous blonde-haired saint; she leaves it loose and flowing, as if to spread her charm. Rather than in the Gospels, it is in The Golden Legend by Jacobus de Varagine that we learn about her hair, as well as about her family (her parents, Syrus and Eucharia, and her sister Martha, who slaves away in the kitchen). When Mary Magdalene meets Jesus, it is a miracle: she repents of her chaotic lifestyle, and becomes his most faithful follower. The moment when Jesus resurrects her brother Lazurus, Mary Magdalene washes the feet of Christ with her tears and perfume, and then, abandoning any vanity she once had, she dries them with the most precious linen: her long hair. This legend by Jacobus de Varagine is made entirely of gold, just as the golden hair of Mary Magdalene steals the show from Jesus in Masaccio’s Cruxifiction made in 1426. She is depicted at the feet of Christ, with her arms open and raised upwards in the dramatic gesture of ‘wailers’ (women who, according to the Mediterranean tradition, mourned loudly during funeral ceremonies). Her bright blonde hair is even more vivid than the golden background, and enhanced by the intense red of her dress. Longhi argues that Masaccio inserted the figure of Mary Magdalene at a later point, after the other figures in the Cruxifiction had been painted. Jesus’ favourite follower finds room in front of him, as the converted seductress. Alongside the perfect divinity of the Virgin Mary, who is a model of controlled pain, Mary Magdalene is a human woman: her flowing hair, once part of her immoral lifestyle, becomes a symbol of humiliation and elevation through which she initiates her new existence.

Carlo Crivelli’s penitent Mary Magdalene is icy and erotic. She is depicted with beautifully styled fair hair. These idealised hairstyles, adorned with such abstract perfection, should have represented the spiritual elite, but in fact were shamelessly worn by the earthly elite. Mary Magdalene carries the objects of her penitence in her hands: a small vase of perfumed oils (in which, according to a strange legend, the umbilical cord of Christ was stored) and the jewels that she discards upon beginning her path to redemption. After Christ’s death, Mary Magdalene lives out her life as a hermit. The Golden Legend relates that, after preaching the ‘Good News’, evangelising Provence and performing some miracles, the penitent Madgalene lived the last thirty years of her life in a cavern in Sainte-Baume. It was there that, naked and in solitude, she was covered only by her hair, that grew longer and longer. Her hair becomes even more luscious and thick than that of Lady Godiva, or even of Saint Agnes, the patron saint of hair (when forced to walk around naked in public as a punishment for her Christian faith, her hair instantly grew down to her feet and covered up her whole body).

In Donatello’s wooden sculpture Penitent Magdalene (1453-1455), she is depicted at the end of her life, skeletal, contrite, and without any charm; her flesh mortified and covered in unkempt hair. By contrast, in the Lower Basilica of Assisi, Giotto and his assistants painted seven stories from the life of Mary Magdalene in the chapel named after her. In these depictions, she is only covered with an audaciously thin slither of hair, as if to reference her lascivious origins. However, now fully absolved, with modest sensuality she elevates herself by praying with the angels seven times a day.

In 1482, Tilman Riemenschneider sculpted Mary Magdalene as a hermit. Along with the long hair from her head, hairs grow all over her body. It raises a hairy question about the hirsutism of Mary Magdalene, who is covered in a light fleece, as if a human sheepskin. She is going through a process of becoming a feral woman but, as Leonardo says, ‘Savage is he who saves himself.’

Bibliography

Daniel Arasse, Non si vede niente, Einaudi, Torino 2013

Virtus Zallot, Sulle teste del Medioevo, Il Mulino , Bologna 2021

A.P. Macinante, Erano i capei d’oro a l’aura sparsi. Metamorfosi delle chiome femminili tra Petrarca e Tasso, Salerno Editrice, Roma 2011

Joseph Bédier, Il romanzo di Tristano e Isotta, Tea, Milano 1988

Chiara Frugoni, Vivere del Medievo, Il Mulino, Bologna 2017

November 25, 2021