Naoki Sutter-Shudo, monuments and icons

In crafting speculative worlds on a shrunken scale, Naoki Sutter-Shudo dislocates us from the abstraction of the impending future, allowing a site for contemplation of reality

When we FaceTime on what is a sunny Los Angeles morning, Naoki Sutter-Shudo describes his practice as driven by a ”a personal hunger for looking at things,” with the urge to look at things for a long time. On one level, his work takes a true formalist approach, in which his acute understanding of colour, shape, and texture materialise in finely composed sculptural forms, as well paintings and photographic prints. On another level, there is a mythical quality to the work. When observed from a bird’s-eye view, his sculptures present as unique environments which often reflect fantastic architectural imaginaries and even the cosmos. There is a strong awareness of nature, history, and time in the work. In sculptures such as Dispenser (saturns) (2019), Podium (moons) (2019), and Theft (earths) (2018), he mostly deconstructs our planetary system, cheekily minimising the cosmos to a comedic scale, but also one that enables reflection of one’s place within this structure. In building on the scale of architectural models, Sutter-Shudo reimagines the magnitude of celestial bodies as humble monuments, allowing viewers to consider a new form of monumentality.

Naoki Sutter-Shudo, Podium (moons), 2019 Wood, enamel, stainless steel, nickel-plated steel, polyester and cotton, foam stress balls 14 x 14 x 7.75 in (35.6 x 35.6 x 19.7 cm). Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecoeur, Paris.

Naoki Sutter-Shudo, Theft (earths), 2018 Wood, enamel, plexiglass, nylon, stainless steel, foam stress balls 12 x 28 x 13 in (30.5 x 71.1 x 33 cm). Courtesy of the artist and Bodega, NY.

Born 1990 in Paris, Naoki Sutter-Shudo grew up in Tokyo, where he was surrounded by antiques, spurring what he calls his “attachment to objects.” Following high school he returned to Paris to study Literature and Philosophy before enrolling in École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts. Inspired to be in a city amongst artists such as Mike Kelley, Paul McCarthy and Jason Rhoades, he spent a six-month exchange at ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena where he was involved in the underground literary scene. He split the following years between Paris, Tokyo and California, and eventually settled on Los Angeles, where he lives and works with his wife, the painter Alexandra Noel. In addition to showing his work with Bodega gallery in New York and Galerie Crèvecoeur in France, he co-directs the Chinatown gallery Bel Ami and the small publishing press Holoholo Books. This spirit of collaboration and presenting the work of other artists stems back to his art school days when he was involved in running the highly influential yet now defunct Belleville artist-run space Shanaynay in Paris. These many projects keep him busy—this fall, his solo exhibition at Galerie Crèvecoeur in Paris opened the same week he presented new work at their booth at Paris Internationale, all while he managed Bel Ami’s booth at Foire Internationale d’Art Contemporain (FIAC).

His 2018 show Mœurs at Crèvecœur, Paris most directly explored the legacy of monuments and icons. In October 1941, the Vichy regime in France decreed that statues and monuments made of rare, non-ferrous metals were to be melted down and the metals extracted for alternative uses. The damned statues were allegedly chosen for having “no artistic or historic interest,” though, unsurprisingly they represented figures that did not align with Marshal Pétain’s views, and so they were siloed out from public visual history. While the technique for rendering figures remained largely the same, the intention on who to publicly consecrate shifted. The Mœurs or morals of the time transitioned so as to uphold political posturing. For Sutter-Shudo, this incident is instructive in thinking about the terms in which some icons are preserved and new symbols emerge. National iconography is both specific yet boundlessly universal. For example, the red, white and blue of the French flag is reflected in many other international flag design iterations, though for the French is culturally specific and enters into the stage of iconography in works such as Pas encore titrés (1968-2018) and Plumeau Cocarde (2018). Time is the condition by which the forces of politics and culture intersect and adjust. Sutter-Sudo reflects that from the French Revolution to now there are transformative periods in which people try to “obliterate older systems and ways of doing things and come up with new measurements for time.”

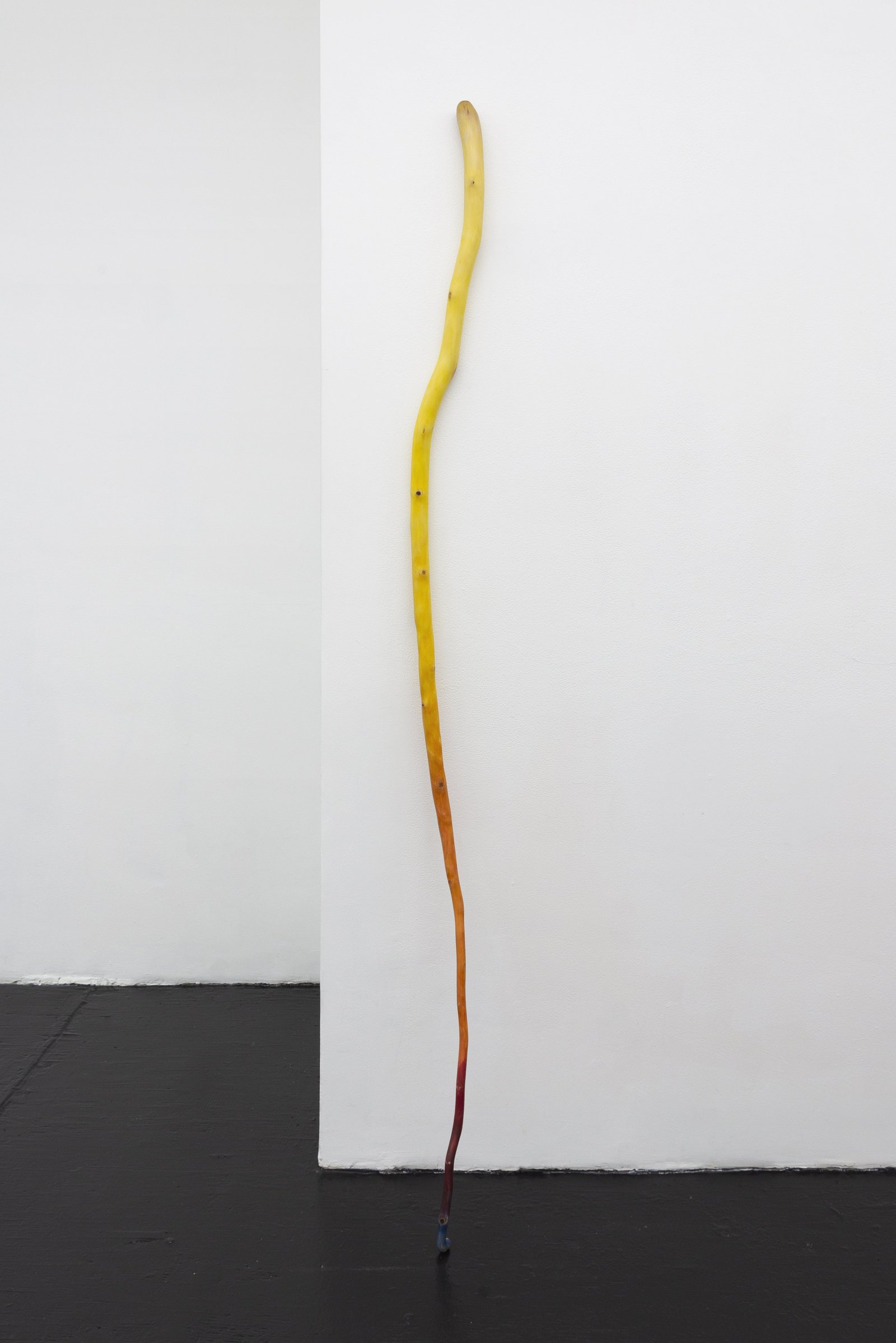

Naoki Sutter-Shudo, Stick, 2021. Dyed wood 69 in (175.3 cm) long. Courtesy of the artist and Bodega, NY.

Naoki Sutter-Shudo, Stick, 2021. Dyed wood 69 in (175.3 cm) long. Courtesy of the artist and Bodega, NY.

Naoki Sutter-Shudo, Stick, 2021. Dyed wood 69 in (175.3 cm) long. Courtesy of the artist and Bodega, NY.

Naoki Sutter-Shudo, Stick, 2021. Dyed wood 69 in (175.3 cm) long. Courtesy of the artist and Bodega, NY.

For his first gallery presentation following coronavirus lockdowns, Sutter-Shudo presented a series of attentively carved sticks at Bodega gallery in New York. In Don pur de la nature (2021), he focused on the tactility of forms to celebrate the physicality of objects during a time in which screens held reign. Time becomes the marker for the progression of the work—dictating the smoothness and the curvature, the relationship between artist and object. Across all of his works he takes care in making, with the belief that “time necessitates time to make something, in which the more time [he] spend[s] on something, the more time that thing will be able to live through or survive.” He notes that “energy is embedded into objects.” For him, “the pleasure of making the object can translate into the pleasure of witnessing a beautiful object.”

Naoki Sutter-Shudo, Tol, 2021, wood, enamel, stainless steel, polyester, ivory, 101 x. 56 x 38.2. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecoeur, Paris.

Naoki Sutter-Shudo, Tol, 2021, wood, enamel, stainless steel, polyester, ivory, 101 x. 56 x 38.2. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecoeur, Paris.

Circling above a sculpture in his most recent exhibition, Sculpture at Crèvecœur, Paris, one can imagine Sutter-Shudo making the work—lifting a piece of wood to eye level and finely crafting and assembling it in his hand, to create a piece that is “seductive, yet attractive,” with the hope of “maki[ing] tragic things look beautiful.” Ultimately there is a sense of grave reality in the work—a tragedy in the precariousness of our future as humans on this planet, largely due to climate change. In crafting speculative worlds on a shrunken scale, he dislocates us from the abstraction of the impending future and allows a site for contemplation of reality. Ultimately, Sutter-Shudo is crafting for a sect of the future in which there is space for imagined alternatives.

November 24, 2021