Guariento di Arpo relaxes perfection

Guariento di Arpo’s response to the authority of his Padua predecessor Giotto is one where grace blends with Gothic style and humanism

Pictorial perfection ruled among artists in 13th century Padua. Mater perspectivae picturae, “the mother of painted perspective:” this is how the Euganean city was addressed. Crowds of scientists, opticians, builders, and ladies friends of the arts who bore the virginal names of Fina, Lieta, and Giliola gathered on the city’s squares, those corners now called “Duomo”, “Signori,” “delle Erbe,” and “della Frutta.” Padua was known to be a crossroad between art and science, a balance that the lords of the city, the Carraresi, strenuously protected. Great Aristotelian philosophers lived in Padua, first of all Pietro d’Abano, professor at the University, scholar of Islamic medicine, and friend of Marco Polo, but also Lovato Lovati, Albertino Mussato, Marsilio of Padua, Biagio Pelacani, and the Dondi dall’Orologio’s. This circle of pre-humanist intellectuals was responsible for the foundation of modern justice and science, and is now key to understanding the painting of Guariento di Arpo.

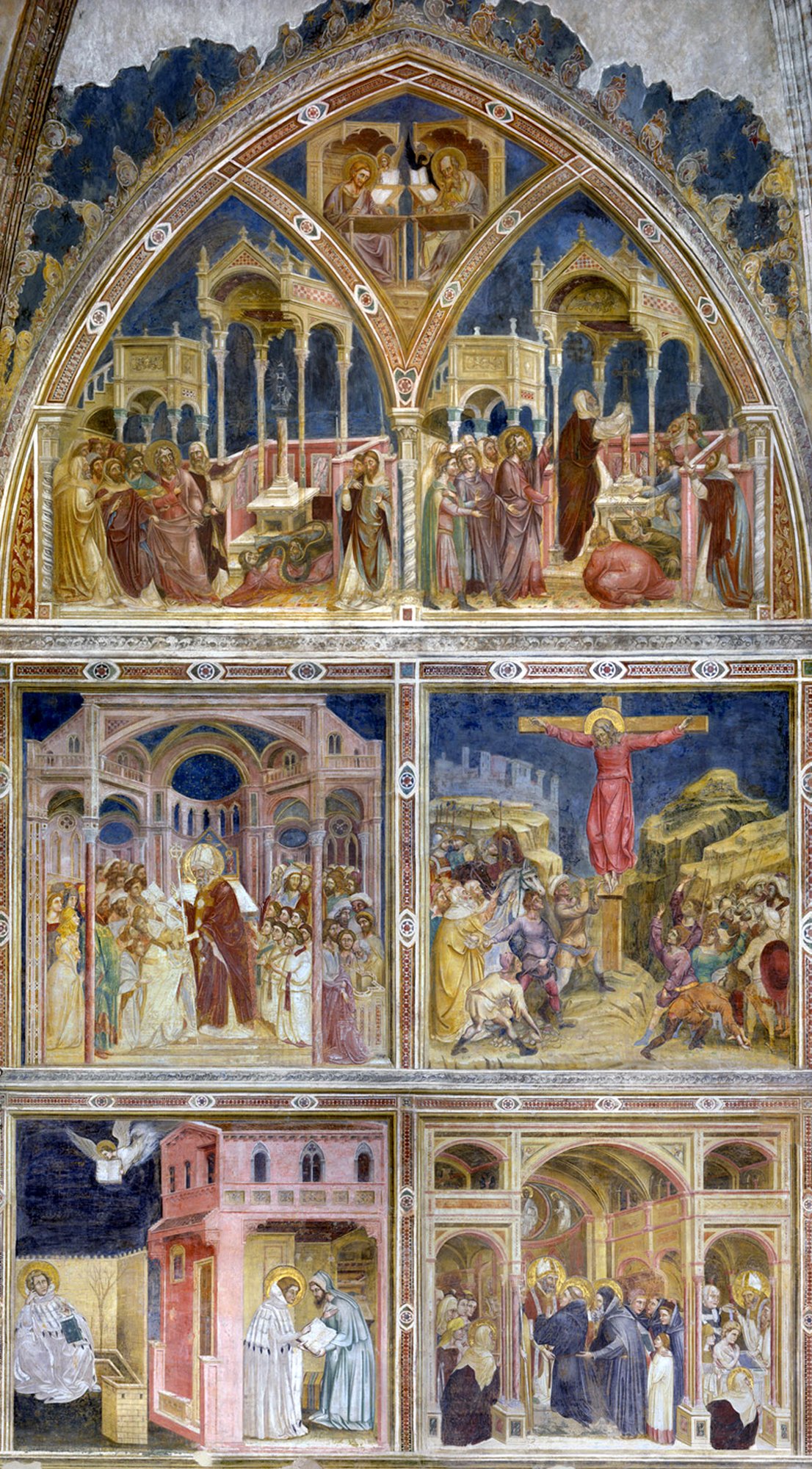

To the untrained and uncertain eye, Guariento might come across as belonging to darker times, especially given his almost aristocratic, dare I say haughty, theological finesse. However, the city of Padua during Guariento’s life was more enlightened than the dark times it would experience in the centuries to come, and this conservative image of Guariento quickly disappears after a deeper look. Despite the cultural ferment of his city, and indeed precisely because of this, his life as an artist must have been tough. Born five years after the departure of Giotto and Giovanni Pisano (presumably around 1310), Guariento had to deal with their omnipresent legacy in town, attempting to respond to their achievements from an early age – Guariento was already painting at fifteen and wherever he looked, he would see perfection. Artists from the same period like Giusto de ‘Menabuoi or Altichiero are not comparable with Guariento, first of all because the latter did not move to Padua but grew up there. This means that Giotto is an unquestionable reference for Guariento rather than a chosen master like he was for others.

Giotto achieved theological, philosophical and artistic perfection through his paintings in the Scrovegni chapel and the Palazzo della Ragione, de facto putting an end to an era. Times were changing though. New ideas inspired by astrariums, magic, tales from China, hinting at the separation of state and Church (the Defensor Pacis by Marsilio dates back to 1324) reached Guariento. Immersed in this climate, the artist faced the same dilemma that torments every artist living in a “post” era. If the world is changing, how can one surpass the perfection that’s already been achieved? As a follower, commenting on it? As a reactionary, violating it? In 1325, Guariento understood that perfection should not be stubbornly sought, nor scandalously betrayed, but dissolved, freed, slightly played down. Guariento knew he would never beat Giotto at his own game. At the same time, history decided that Guariento would never anticipate a modern painter like Mantegna. It was not his destiny to revolutionize painting and to strive for unitary and peremptory beauty. Guariento instead glorified grace with his style, seeking a gentler and freer kind of beauty.

[More on the revolutionary Mantegna through his relationship with Antonello da Messina here. Ed.]

Although Guariento’s distinctive grace is found in many of his paintings, I will focus on what used to be the decoration of the chapel in the Carrarese palace, the angelic hierarchies, now preserved in the Pinacoteca of the Eremitani Museum in Padua. Before anything else, the role of Venice and its Byzantine influences need to be mentioned to better introduce these works: whether the grace and kindness of Guariento’s art directly responded to the hieratic and violent style found in the Lagoon City was an art historical controversy until the 1960s, when it was resolved by scholar Francesca Flores d’Arcais. With his splendid prose, Sergio Bettini summarizes the issue as follows:

Guariento di Arpo is a very Paduan figure, grown into a pictorial culture in which the authoritative style of Giotto left an indelible footprint. Giottism in Padua is a sort of linguistic dimension [“a matter of linguistic structure,” Bettini had previously written] with which an artist must deal, but it also becomes, with the passing of the decades, the term of a meandering, implicit controversy. Guariento overcomes the question by steering away from the gold of the late Byzantine “province,” approaching instead the effusions of the Emilian “bourgeois” Gothic from Rimini, […] but also the wandering Bolognese and Modenese [styles]. One should not forget the miniatures of the Paduan scriptoria […] either. Finally, in Venice itself, or in contact with Venetians, Guariento fell for what was still Gothic in them, rather than Byzantine.

On the one hand, Guariento soaks in the influence of Giotto: his naturalness, his interest in spatiality, architecture, interiors, plasticity, softness, and the precise details of human faces. He follows the reality that through color finds materiality on the flat surface without ever abandoning the meta-pictorial subtleties. On the other hand, Guariento demonstrates a certain courtly style that superficially resembles Byzantinism, as it is ornate and precious, but which in fact reverberates not from the hieratic nature of Byzantine Venice but from the swarming of the new Paduan bourgeoisie and its new search for beauty.

In a 2011 article, Monsignor Claudio Bellinati self-consciously attributes to Guariento a Franciscan spirituality combined with a profound Augustinian theology. What is certain is that the painter did depart from Giotto, who also followed an Augustinian theology, by choosing the angelic hierarchies to decorate the Carrarese chapel in 1350. One kilometer away and about fifty years after Giotto’s Scrovegni frescoes, which revolve around the Salvation, the humanity of Christ, and the redemption of the soul, the narration of Guariento’s chapel instead focused on divine power. Giotto’s starry sky in the Scrovegni is the divine that guards the unfolding of history. Guariento chose angels instead, that is, the figures of the eternal. Was he attempting to forget the passing of time in the years of the Black Plague? Is there even a more complex explanation for such a radically different choice?

Francesca Flores d’Arcais refers to the angels of Guariento as “feminine,” “transhumanized,” and “completely Gothic” creatures. “They are crossed by a line that bends them in the typical Gothic hanchement, clothed in draperies where even the shadows are imbued with color.” The movements of the angels are sweet and the colors of their flesh and clothes, which are spread over a greenish tempera primer, are clear and soft, giottescamente soft, slightly chiaroscuro, and in contrast with the more decisive tones of the wings.

From the highest to the lowest orders, here are Guariento’s angels, materialized in tempera on poplar boards. First, there is the order of the Cherubim, the angels who guard God and Eden and who, together with the Seraphim, have a direct intuition of it. They are the only ones Guariento paints with no naturalism. They have six wings and hold a wheel bearing the inscription Plenitudo Scientiae. Just below is the order of the Troni’s: they translate, communicate, and implement divine intelligence. Guariento depicts them sitting on a throne. They hold the spear and the globe. Two of them on a trapezoidal table sit admirably disheveled, almost intrigued or amazed by something that happens outside the composition – a bizarre attitude for an angel of the high order. Here is also the order of the Dominazioni’s, who dominate and regulate the tasks of the lower angels. They are depicted in a group, inside a circular frame that features a primitive, funnel-shaped perspective.

The Virtu’s order are the angels of fortress and creation, of what evolves like natural creatures. They are responsible for miracles. Guariento represents them with a lily in their hand, slightly bent towards the created world. In one table, a Virtu angel indicates a mountain stream, as if she were responsible for the flowing of the waters; in another, she lovingly rests her hand on a beggar and a cripple who seem to be the exact prototype of the couple of infirm healed by the shadow of St. Peter painted by Masaccio in the Brancacci Chapel in Florence. The Potestà’s order are the angels of wisdom and conscience. Unarmed, they drag a devil with a rope tied around his neck, taming him. Every noose depicted by Guariento cuts the composition into different angles, creating different force dynamics from table to table. Guariento’s diagonal lines are so robust that they affect the angel’s expression, making her look satisfied, or in physical tension, proud, or even sadistic I’d dare say. The Principati’s are the angels of history and time, of politics, accompanying humanity along their path of discoveries. Guariento depicts them with shields, armed with spears, with cloaks, dressed like the Paduan bourgeoisie of the time. In other representations they are in a group, aligned as ready for war, painted on a gaseous and cloudy background.

Down below, the Archangels are the messengers between the celestial and human spheres. According to some angelological tradition, they are of fundamental importance in the Last Judgment. Guariento depicts them in the act of weighing souls; they too hold a spear designed to stab a little devil. Finally, the common Angels are the lowest and closest to humanity, holding a small soul in their hands. One of them, on a trapezoidal table, is kneeling and seems to be holding it like a child would hold a bird.

Some interpretations of Guariento’s angelic hierarchies are more controversial than others, for example scholar Franca Pellegrini thinks that those angels thought to be Dominazioni’s by Flores d’Arcais are actually Seraphim. A few things are certain though: these angels are not like stars or planets following absolute celestial motions; they are not like stones stuck in the immutability of time; they are not mere ornamentation, but busy creatures, grappling with collective and individual history in the lowest sphere, with ethics and the ordering of creation in the intermediate one, and with the interpretation of God at the highest levels. “Cherubim interpretatur plenitudo scientiae, Seraphim autem interpretatur ardentes sive incendentes” [Cherubim grasp the perfection of knowledge, Seraphim are active or kindling] writes Aquinas in the Summa Theologica. Nothing seems closer to Padua’s motto than the cherub who “understands the perfection of knowledge.”

By igniting Giotto’s plasticity with Gothic lines, Guariento is also among the most skilled painters of the female face of his time. Some of his female figures are beautiful according to extremely modern canons – the higher the hierarchies, the more feminine the faces of his angels, especially those in a throne with soft and rounded complexions. On the contrary, the lower Principati’s are portrayed with accentuated henchement and some virile details such as the protruding belly, short legs in respect to the torso, perfectly mimicking the proud, even braggart warrior.

Men and women dedicated to the natural elements, to wars, to the interpretation of the transcendent, to imparting ethical principles, to the medication of the sick; angels protagonists of events, bodies in movement that express immanent emotions: I do believe that Guariento’s angels represent a society rather than a theological hierarchy. What if, in addition to being closer to Giotto than Venice, he was also closer to the humanism of Dante than the spirituality of St. Francis? What if a pre-humanist painter was actually hiding behind a precious, gothic soul? He was indeed the painter who talked about history without resorting to biblical episodes, instilling secular history in the common angels, the scientist in the Virtu’s, the politician in the Principati’s, but also the judge, the doctor, the philosopher, and the poet in the various hierarchies.

My thesis cannot be validated here, but if I were right, Guariento di Arpo would become a closer kin to Giotto and his dedication to the human, dissolving the perfection of Giotto with the graceful lines of courteous society, but with the preciousness of a style where the golden yellow was more and more leaving room to the pink of human flesh.

Bibliography

C. Bellinati, Guariento Teologo. Studi e ricerche per una nuova biografia, “Padova e il suo territorio”, XXVI, 151, giugno 2011

F. Flores d’Arcais, Guariento. Tutta la pittura, Venezia 1974

F. Pellegrini, Guariento e i dipinti dell’Accademia Galileiana,in Da Guariento a Giusto de’ Menabuoi. Studi, ricerche e restauri, Treviso 2012

www.academia.edu/11613902/La_concezione_agostiniana_del_programma_teologico_della_Cappella_degli_Scrovegni

February 10, 2022