Famous questions and the paintings of Sofia Silva

The paintings of Sofia Silva do not want to please. Here, questions are prompted as to what they offer instead

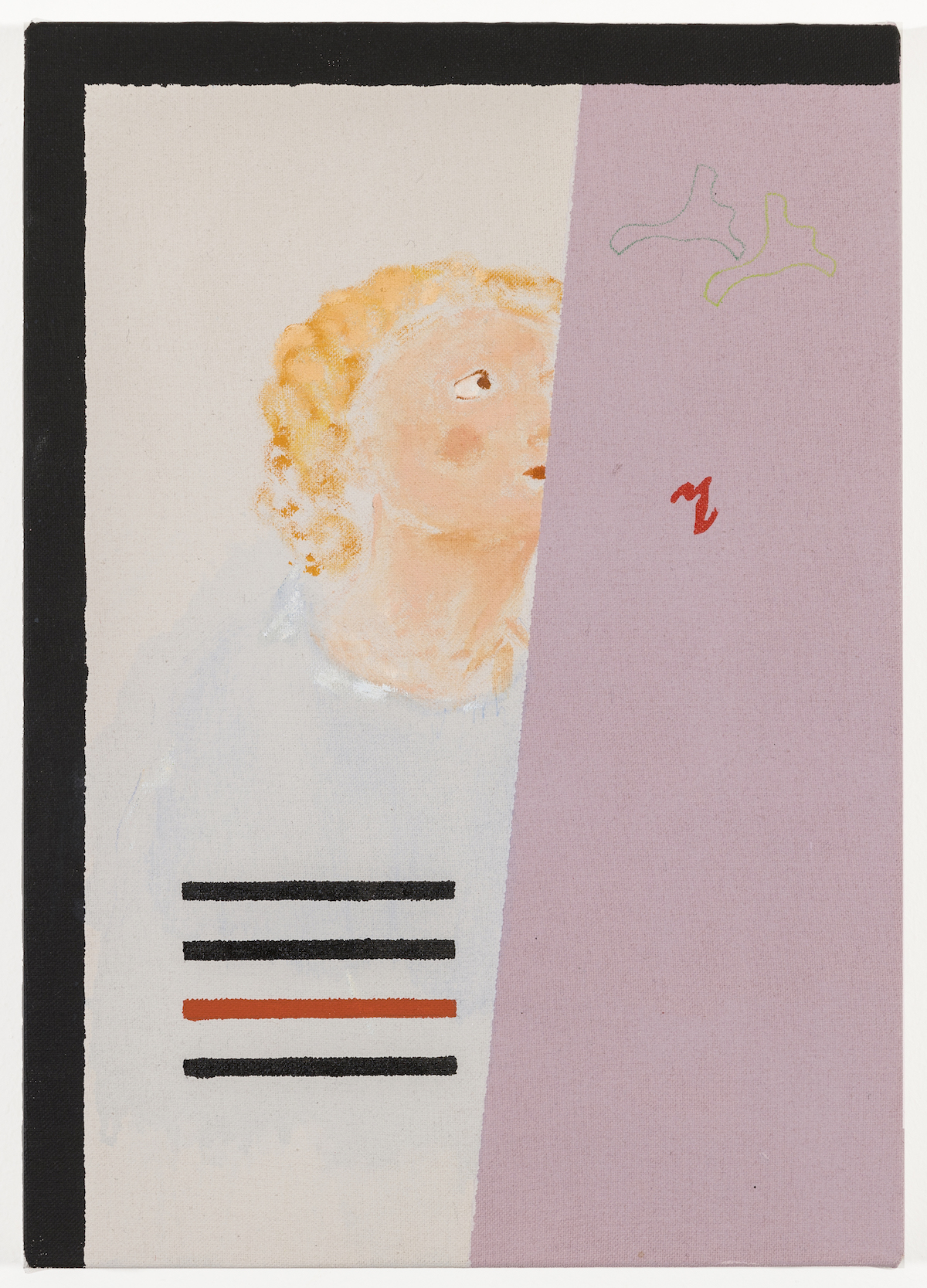

Sofia Silva founds her painting on negation; in what she does not appreciate, and thus rejects. She shows us what is left of a painting after beauty, emotion, subjectivity, referentiality, expression, fiction, illusion, ideology have all been excised – what?

Short answer: Remains. These are pictures of scraps and mutilations that testify to a combative relation to herself as an artist, and to painting as such. Collage – a meeting between image profusion and fragmentation – can be said to be at the core of modernism because it gives form to the alienation and confusion of the modern individual. In Silva’s practice, it is the work itself that is being collaged: not mediated society, not collective identity, but the initial impulse of the painter, dissected, analysed, partly discarded and, in some form, allowed to emerge.

As a viewer, you wish the painter would indulge in spontaneity to create something more pleasing, more alive. At the same time, the fact that she directs her effort, painstakingly, towards innovation and singularity, that this restless energy is applied with such rigour and intensity, goes some way to replace the pleasure usually afforded by expression with intrigue. What does Silva want from these pictures? And what can they give to their viewers?

In paintings such as Aniseed Pen and Chilli Pen, both 2022, we see traces of the grid structures of a Mondriaan – in Chilli even the familiar De Stijl palette – with added crooked shapes and mysterious, meticulous signs: in Aniseed, small triangles, or arrows, like those that describe the movements of pressure fronts in a weather forecast. They add a certain dynamism to the composition, but, like every other element, they are add-ons paradoxically averse to adding up; you follow the arrows and get nowhere. Instead, you are met by the question of where it was you thought you might go. What would be the destination?

Modernism was on a trajectory towards nothingness, spiritual at times and nihilistic at others. Robert Rauschenberg’s Erased De Kooning Drawing, 1953, is such an apt illustration of the idea of teleological progression as an act of cyclical patricide that nonetheless reinvests in the image of the father. There is nothing left of the drawing but a vague outline, a void pregnant with the story of painting and its protagonists. Anything since added to this story by postmodernism would be understood to be empty, pure style. What is at once special and difficult about Silva’s paintings is that she observes the nothingness of modernism but refuses to accept the emptiness of postmodernism. Or put differently: what she adds to the picture is matter without style; something of consequence, but what?

The most promising features in Chilli Pen are two clusters of brush marks in pale orange, lilac and maroon, reminiscent of a 19th century cloud study. They are what Silva calls “little windows of romantic feeling” [1] – and, indeed, how near you are to feeling something just then. However, their promise is soon let down by the extraordinarily clumsy star shape underneath (a child’s Christmas decoration) and the harsh toothy fringe below it. The windows must be closed. “I am against illusion in painting”, she told me, “against melancholy. I don’t trust narrative or my gut, and I don’t want to.”

With this attitude, Silva is working very much after the German painter Michael Krebber, whose repertoire is one of “end-game manoeuvres” as Jessica Morgan writes in Artforum, “The weight of his inheritance makes room for just the slightest of activities.” [2] We watch Silva struggle with the scraps that were left in his wake and realise just how little is possible. His famously ridiculous snail haunts the unforgivably unattractive ladders and skinny carrots that crop up on Silva’s canvasses as well as her preference – or likely, the exact opposite – for kitschy pastels.

But where Krebber may exercise a certain formal restraint, his “bad paintings” do represent an indulgence in melancholy that is rich in pathos. This is a kind of masculine defeatism, sure, but it is also what makes them poetic and sometimes even beautiful. Silva’s energy is different in that it is not defeated. In and through her paintings, she searches for answers to some Krebber-esque predicament with such zeal she is willing to forego almost all of art’s usual rewards to find them. Although there is a kind of beauty in that, one she describes as being linked to “abstinence, purity, freedom,” as subjects of liberal capitalism we know that freedom is a trap, its price inordinately high. We have to be able to answer the question of what freedom is for, just as the painter must answer the question: why paint? So why does Silva paint; what is it, I ask for the third time, that the expensive autonomy and stubborn impersonality of her paintings offer us in return?

I could latch on to her sad eyes in Self-Portrait Surrounded by Signs, 2022, or load existentialism onto the smallness of the figures that dot the landscape in Primo Mobile #4, 2021, but she doesn’t want that, I know, because the ladder next to them is too awkward for my depth of feeling to survive it. However, in this back and forth between the desire for beauty or recognition and realising the impossibility of it, more famous questions arise: what is ugliness? What is feeling? Why do we ask objects to reward us for our attention, and why do we think we deserve it? This bewilderment, I am starting to understand, is what we get. Take it or leave it.

[1] All quotes attributed to the artist are taken from a conversation in Fall 2022.

[2] https://www.artforum.com/print/200508/jessica-morgan-44287

January 26, 2023