The sleeping enigma of the Arundel Pietà by Cosimo Rosselli

In the castle of the Dukes of Norfolk, one of the greatest enigmas of the Florentine Quattrocento lives: a Pietà attributed to Cosimo Rosselli

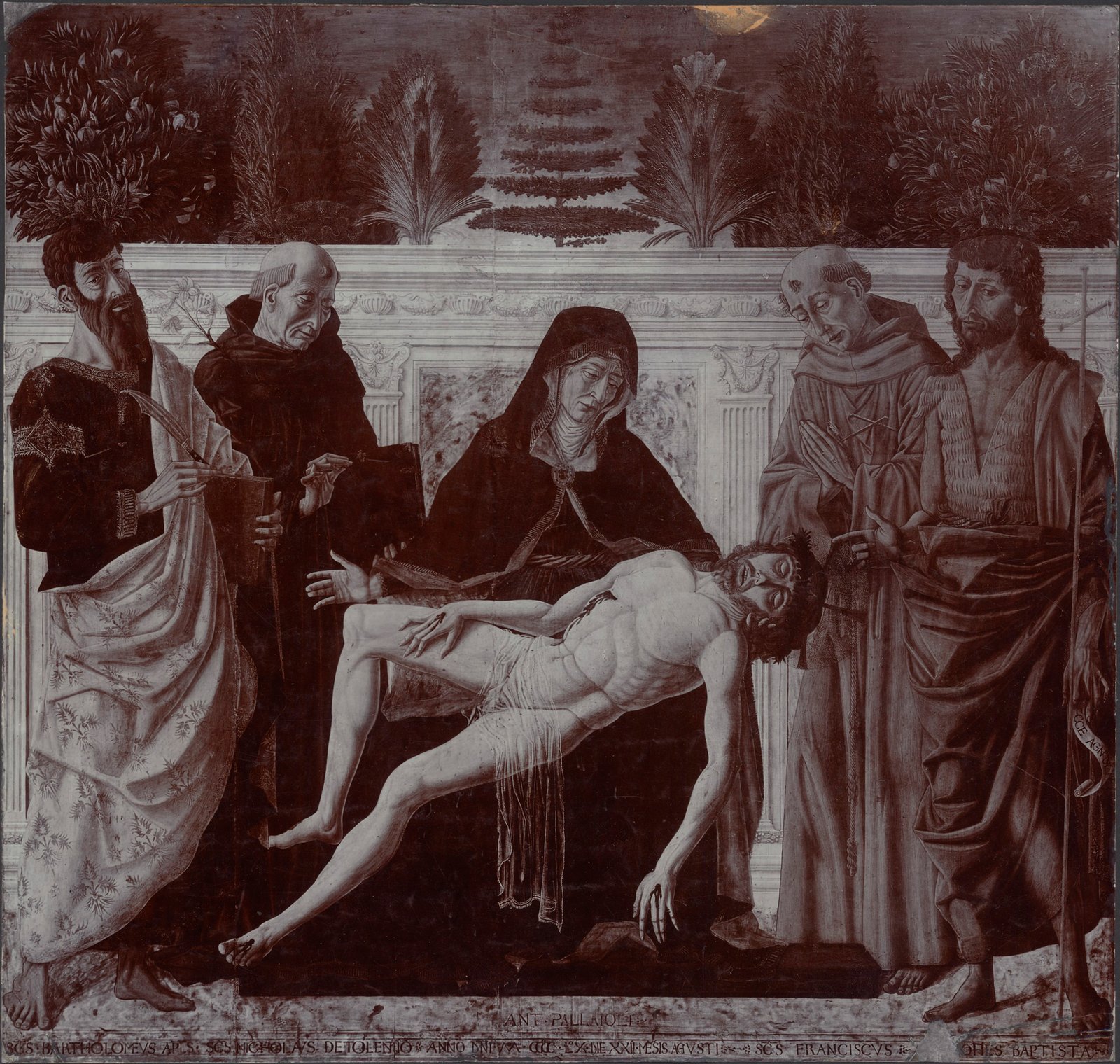

In the reassuring solitude of old photo libraries, among crumpled files, it can still happen to come across works that are not popular, ignored even, now resting in unknown locations. These are homeless paintings and sculptures whose intricate stories rich in daring events have left them at the mercy of the most capricious circumstances. Some of these homeless works might eventually land in an institution or reappear on the antiquarian market, rekindling new interest and immediate critical re-evaluation; others remain in the shadows, only living in old photographs from dusty archives. Among these is a painting on panel attributed to a Florentine artist from the third quarter of the fifteenth century, a work that continues to represent one of the most seductive, and therefore irresistible, art historical enigmas. It is the Pietà between Saints Bartholomew, Nicholas of Tolentino, Francis and John the Baptist by Cosimo Rosselli, once reported in the Arundel Castle, the fairy tale home of the Dukes of Norfolk.

From Bernard Berenson to Roberto Longhi, to Federico Zeri and Everett Fahy, all the most perspicacious art connoisseurs of the last century attempted to decipher this work. However, none of the proposed interpretations, albeit captivating, turned out to be completely convincing. As happens in particularly problematic and ambiguous cases such as this, a plethora of interpretations has discouraged alternative readings: for the last three decades, no other hypothesis has been advanced, nor an old one accepted, rejected, or even just reconsidered. The presence of a precious and authentic date (August 22nd, 1460) at the bottom of the painting, albeit a significant chronological clue, has offered no further clarity.

This Pietà’s bizarre style, along with its mysterious history, contributes to its lack of popularity in recent times. Judging from the beautiful photograph at Villa i Tatti, the painting features a great deal of odd details: the absurd myogenic paroxysm of Christ’s ribcage on the verge of crashing, the illogical affectation with which the saints Bartolomeo and Nicola flaunt their hagiographic bows on their fingertips. The same goes for the faces of the protagonists: the sad wrath of the Baptist, the thoughtful Francis, the tearful Virgin, the gloomy contemplation of Nicholas, and Bartholomew’s unbearable gaze that aims at the soul.

The most remarkable feature in the work remains the dead body of the Christ, on which most interpretations have focused. This corpse has been rendered with some taste for the macabre: the bones are obsessively highlighted; the tendons look like one could pinch them; the muscles bundle and dry up, right down to the face, where the shut eyes emerge from the sunken orbits. The style continues in the figures nearby – the Baptist and Francis especially – where feet, hands, and faces are painted as if they were a parchment or an iguana skin. This expressive and dramatic tension, bizarre even, develops also in marginal parts of the painting: the leaves on what looks like orange trees (rather like two forests of very sharp razors that dissuade us from picking the fruits) and rows of shaggy cypresses, innumerable in their crowded group. All of these elements are drawn by an energetic hand, almost neurotic, with little stumbling that nonetheless doesn’t diminish the acute impression of being in front of the work of a remarkable painter. Prominent figures of the Florentine Quattrocento, most notably Antonio del Pollaiolo, have been occasionally suspected to be the mysterious maker of this work.

When the Sienese historian Gaetano Milanesi first mentions the Pietà in London, he attributes it to the famous Florentine master, who seems to have signed the picture with pseudo-ancient characters – “Ant Pallaiolo” – at the bottom. After restorative work in 1922 and an illustrated article by the critic Roger Fry, the signature was proven false and an entire debate on the attribution started again: Fry himself attempts an answer, proposing the name of another major Quattrocento figure, Andrea del Castagno, whose approach to anatomical drawing he found in the Pietà in question. More precisely, Fry believed that del Castagno was responsible for the preparatory drawing and one of his pupils for the subsequent overpaint. Fry’s convoluted attribution was later dismissed by Bernard Berenson, who included this “truly remarkable work” in the bulimic and murky catalog of the Master of San Miniato: a mid-tier painter inspired by Lippi, ultimately an exquisitely provincial and monotonous artist to whom disparate works were just starting to be attributed, all kept together by a specific dryness in their drawing style.

In 1952, historian Roberto Longhi introduced a new element of discussion, partially re-evaluating the work in his unforgettable essay on the Master of Pratovecchio. Here, in one of the last notes to the text, the Pietà was brought closer to a tabernacle never seriously questioned until then, located on the left side of the Florentine Headquarters of the Misericordia, in the narrow via del Campanile: both were reunited with a bunch of other paintings around the painting with Saint Monica enthroned in the Florentine church of Santo Spirito. In Longhi’s concise analysis, the small group belonged to an artist of strict Pollaiolesque observance who seemed to place himself exactly halfway between the great anonymous that Longhi had reconstructed, i.e. the Master of Pratovecchio, and the better known course of Florentine painting of the early 1470s, galvanized by the two “anatomist goldsmiths”, Antonio del Pollaiolo and Andrea del Verrocchio. Subsequent studies were able to demonstrate that almost all the works were realized by the young Botticini, until in the 1960s Alberto Busignani proposed that the short corpus of the author of the Santa Monica was perhaps a young Verrocchio himself, or at least his workshop: a flattering judgment for the Pietà, in case it did belong to this group.

The intelligent thesis of Longhi, who had highlighted a connection between the Pietà and the fresco in via del Campanile was revived years later by Federico Zeri. In 1976, in a succinct entry in a catalog for the Walters Art Gallery in Baltimore, the scholar recognized the same artist in a Madonna and Child from the American collection, proposing that the three works were “an early production of an outstanding Florentine personality ”, possibly Alesso Baldovinetti, Domenico Veneziano, Andrea del Castagno, or Donatello. Although ultimately opting for a generic reference to the Florentine school, Zeri was prone to mention the other Pollaiolo brother, Piero, alluding to the many affinities of his mature results with the American painting and the Pietà. In 1989 the trio thus finally underwent a last and unexpected attributive change, being ascribed en bloc by Everett Fahy to the Master of the Argonauts. If one excludes the unreasonable attempt in 1996 by Luisa Vertova to see only in the Florentine tabernacle a remnant of the Tuscan activity of Giovanni Francesco da Rimini, with which it has nothing to do, the bibliographic review on the enigma of Arundel Castle ends here, offering a range of possibilities.

I believe that the Pietà, the tabernacle and the Baltimore Madonna should be considered together, on the basis of what Zeri supposed: not only from the clear compositional and stylistic affinities between them, but also from the results of the following studies, which in better specifying the outlines of the artists to whom they had been attributed, they confirm their internal coherence. For these reasons, both the theses of Fry and Berenson, as well as those of Longhi and Busignani, should be rejected without too much hesitation. Fahy’s attribution to the Master of the Argonauts should be seen in the same way; his catalog has recently revealed itself to be the set of incunabula of two painters who were very close during their respective beginnings, but otherwise known in their more advanced activity, Jacopo del Sellaio and Bernardo di Stefano Rosselli. Recovering some scattered Longhian intuitions, Everett too saw the relation between these three works, although he left no paper where he developed the thought. On the other hand, Dalli Regoli has put forward a fleshed out chronology, starting with the date of August 22nd, 1470, found in the Pietà.

These theories and refutations are the ground for my argument here. The Pollaiolo attributions (both the two brothers) should be re-evaluated first, especially in view of Antonio’s early Crucifixion with Saints Francis and Jerome, approx 1455, which shows great similarities in the way the bodies are drawn and painted in the Pietà, but some distance too, especially in the facial expressions. Everything considered, Antonio must have been an inspiration rather than anything else for the author of the Pietà; the same could be said for the younger Pollaiolo, Piero, whose style resembles the painting in question only in the Baltimore Madonna. The anonymous author seemed to have followed the lesson of Piero only from the 1460s.

The Pietà also showcases the features of what’s now known as the Florentine “pittura di luce”, so typical of that decade of the 15th century: the concentrated St. Francis would not appear so sealed in his metallic clothes without the precedent of the one frescoed by Domenico Veneziano in Santa Croce, from which the pose is inspired; nor would the idea of making the tops of orange, palm and cypress trees glimpse beyond a polished marble backdrop be conceivable without Domenico’s brilliant altarpiece for Santa Lucia de’ Magnoli, the Annunciation of San Giorgio alla Costa, and Cafaggio’s Baldovinetti altarpiece. The dogmas of “pittura di luce” are respected even in the details such as in the frieze and capitals in the background, which recall the refined environments of a painter sensitive to this type of effect like Fra Carnevale. And lastly, the overall harshness of the Pietà cannot be but a reflection of the calloused humanity of the Master of Pratovecchio.

This reference to “pittura di luce” vanishes in the meek fresco in via del Campanile, where the earlier, less innovative artistic culture seems to prevail. The heavy shadows, the soft blush on the cheeks, the crow’s feet that suture the eyelids to the cheekbones of Saint John and Saint Anthony the Abbot are in fact some of the unmistakable stylistic features of Neri di Bicci’s art, and so is the typical composition. The fakely solemn, austere air, which is seen again in the grandiose San Giovanni Gualberto di Santa Trinità (but executed in 1455 for San Pancrazio), along with the rendering of the niche with shell, are but eloquent tributes to Domenico Veneziano. A peripheral piece from the same years such as the fresco in the Cardini chapel in San Francesco a Pescia, commissioned to Neri in 1458, is again close to the work in Via del Campanile. The singular coffered ceiling of the sober and luminous aedicule, then, re-proposed tacked into the Madonna of the Walters Art Gallery, is a fairly frequent solution in the altarpieces by Neri in the 1460s and 70s and it is therefore probable that it was perfected at the very moment in which the tabernacle was executed; it can be found barrel-shaped in the Annunciation between Saints Apollonia and Luke the Evangelist now in the Civic Museum of Pescia, dated 1459, tripled in the elaborate loggia of the Annunciation of 1464 today in the Galleria dell’Accademia in Florence, and again in the painting of a similar subject in the church of Santa Lucia del Borghetto, in Tavernelle, completed in 1471. The formal analysis of the three paintings so far provided points to an artist trained during the 1450s with Neri di Bicci, dazzled by the “pittura di luce”, whose style embraced that of the Pollaiolos towards the 1460s.

Rather than “homeless” – the work is still in the possession of the Dukes of Norfolk – the Pietà should rather be considered “sleeping”: its author ready to be woken up in the mornings of today’s art history. I want to put forward the theory that the master of the Pietà is Cosimo di Lorenzo Rosselli, or a very young Cosimo di Lorenzo, to be precise. Neri’s invaluable Memories confirm he was hired in the 1450s as a “galoppino”, a man with many tasks. For just over three years, between May 1453 and October 1456, when Cosimo took his leave to travel to Rome, he found himself in the maze of narrow streets of the Roman Mercato Vecchio district and its population of carpenters, tailors, potters and Jewish moneylenders: It is here that the young painter realized small altarpieces for fair fees.

The first certainly datable works by Cosimo Rosselli are from the end of the 1460s and the beginning of the 1470s: the altarpiece of Santa Barbara, painted in 1468 for the sanctuary of the Annunziata, the panel for San Pier Scheraggio, today in the Uffizi, commissioned in April 1470 for the chapel of Mariano di Stefano di Nese, the Madonna with Child and Four Saints from the church of Santa Maria a Lungotuono, from 1471. Although previous works exist, they already represent the style Rosselli would keep until the end of his career.

The exact evolutionary sequence of the fresco in via del Campanile, the Pietà and the Baltimore Madonna is an example of the tortuous process that led the artist to elaborate his recognizable language. In the Madonna, the detail of the ankylosed hand with the snapping little finger, already stripped in the Baptist of the Pietà, is a prelude to the folded hands of the aforementioned Annunciation and in the Virgin of the Adoration of the Magi now in the Uffizi.

The crumpled drapery, now quite impoverished in its pictorial consistency but which we must imagine in bright white lead and animated by the shadows, is like the trappings of the Evangelists in the ceiling of the Salutati chapel and of the three saints in the Altarpiece of Santa Barbara. Even the sad figures of the Pietà, with their crippled anatomy, resemble the protagonist of the Servi works: the luminous scenography in the freshly plastered architecture is the closest to “pittura di luce” one can find in Rosselli’s catalog known to date.

Finally, the Pietà greatly compares to the Fiesole frescoes by Cosimo Rosselli, especially the silent Saint Bartholomew and the feeble Saint John the Evangelist: his penetrating melancholy, watery and lucid gaze, anxious and venous hand, and insomniac eyelids; they so much resemble the painting in question so that the same person seems to have been portrayed twice, a few decades away, graying and balding.

On the contrary, two panels of evident Franciscan origin with a gold background, with as many saints each, date to a much more advanced stage in the career of Cosimo Rosselli and his workshop. Aldo Galli kindly pointed them out to me in the catalog of an eclectic Norman auction house, listed as “Florence, vers 1480”. They certainly belonged to the same complex of Saints John the Baptist and Francis, kept in the Muzeum Narodowe in Warsaw and attributed to Rosselli by Carlo Ludovico Ragghianti and Federico Zeri. It is difficult to establish the exact configuration of these works together: most likely not a polyptych, as supposed by Edith Gabrielli, due to the small dimensions (only half a meter in height), the deliberate use of the gold background and the modest conditions of the paintings. The works must have instead been doors of an ecclesiastical furniture piece or a cabinet.

The fake marble decoration appearing on the back of the two French panels confirms this hypothesis. The three panels and a missing fourth must have been arranged in two registers, with the two French on the right and the others on the left. The presence of Saint Ursula next to a very select Franciscan iconography alludes to the provenance of the pieces: a Florentine monastery of the same name, occupied by tertiary nuns since 1435, although this possibility cannot be confirmed here. On the other hand, the faded tonality and the poverty of the drawing indicate that they were executed at a juncture not far from the Annunciation and saints in Avignon, of 1473, and of the fragmentary altarpiece assembled from the studies around the Madonna in glory of the Huntington Library of San Marino, California.

As to these works’ author, Giorgio Vasari describes Cosimo Rosselli as an ungifted man, who arrived on the scaffolding of the Sistine Chapel thanks to recommendations and where, skilfully resorting to a profusion of gold and lapis lazuli, he managed to win the praises of a pontiff whom Vasari considered a bigot too. This image of an archaic, somewhat boring and reactionary painter, along with many works of fluctuating quality that have reached our days, must have contributed to shaping the characters of some of Rosselli’s later works: splenic figures, disdainful, with a ruddy nose and well-fed cheeks, with a bigoted and intimately resigned air that persisted until the dawn of the sixteenth century.

The enigma of the Arundel Castle Pietà, with the evolution of the paintings it brings with it, tells us a different story: a painter in his early years who was curious, eager to establish himself, and who contributed with lively interest to the artistic innovations of the time. What prompted Rosselli to interrupt this unpredictable and perhaps exhausting experimentation for an ordinary pictorial existence devoid of pursuits is difficult to know. However, the graphic obsession that runs through his early works, his figurative enthusiasm, his unsuspected disturbances, in short, his most secret mind, is nothing short of surprise.

May 8, 2023