Traveling for the Master of the Corsi Crucifixion

An itinerary that starts with the Master of the Corsi Crucifixion and leads to an important series of Giottesque crucifixes

We are in Florence. Palazzo Davanzati has recently reopened its doors, with its rampant exposed pipes and Petrarchan Triumphs by Giovanni di Ser Giovanni, known as Lo Scheggia, Masaccio’s brother with a marked narrative vein. So has the Horne Museum, which holds Giotto’s Saint Stephen in dalmatic, strong and delicate at once, pearly white with shaded bluish shadows, a masterpiece of calibrated opulence. But above all, the Master of the Corsi Crucifixion has returned to the Academy. Back, indeed, orphaned by the museum that had housed a cross by the artist until 2019, later moved to the Uffizi.

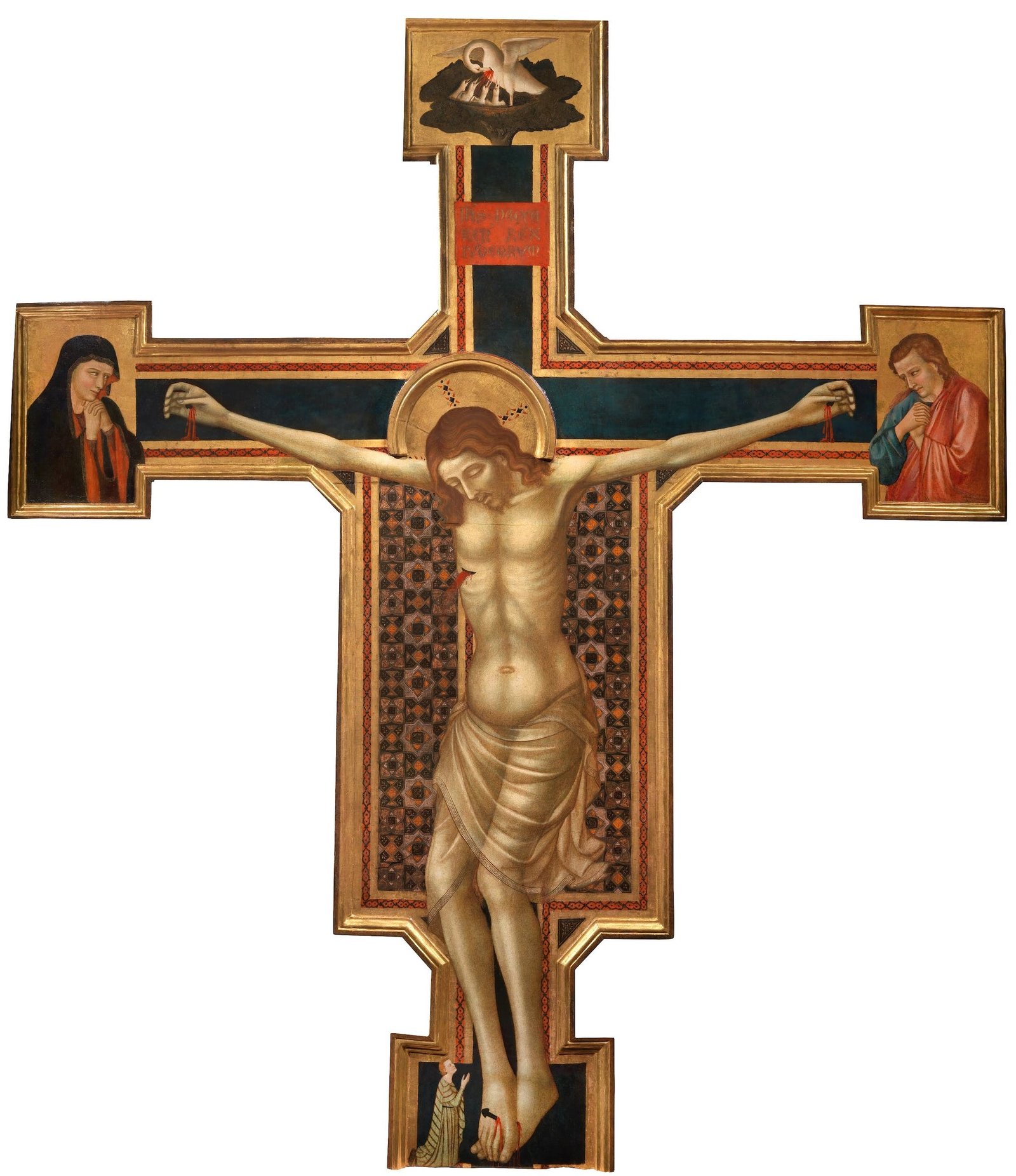

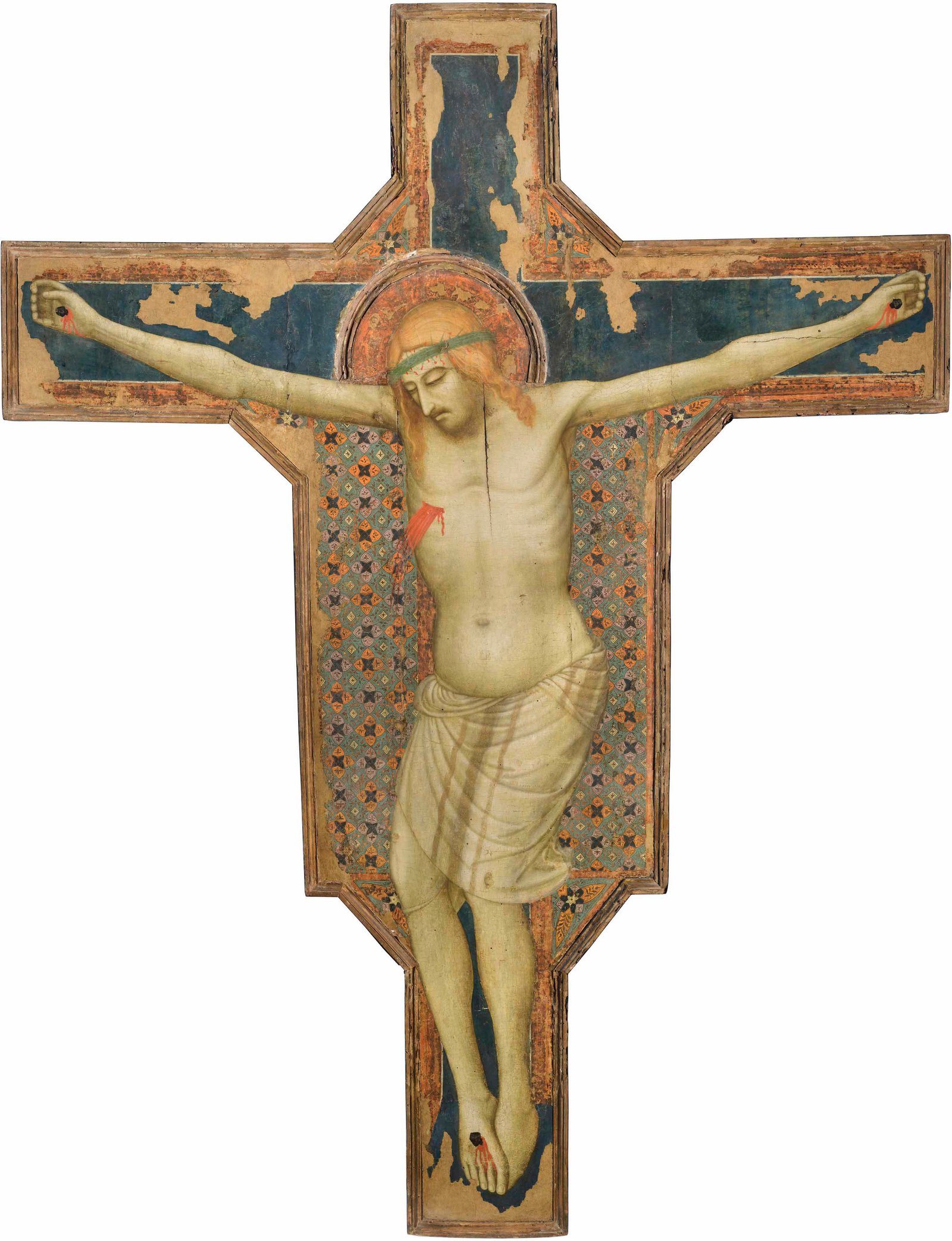

Last September 11th, the announcement: another painted crucifixion has appeared in the room dedicated to the fourteenth century, which happens to be the very one that gave the painter his name! To some, to be fair, the panel is not new. Those who visited the Antiques Biennale last year cannot help but be astounded by antiques dealer Fabrizio Moretti. And it was on that occasion that the enraptured Academy director, Cecilie Hollberg, thought, without hesitation, that the author should be “returned” to the museum. “The Crucifixion belonged to the greatest merchant of the last century, Carlo de Carlo,” declared Moretti, who had bought it on the Milanese market about fifteen years ago. But who is the master? An anonymous Florentine, identified in 1931 by Richard Offner in the Corsi collection thanks to this panel and described by the scholar as “a painter of dramatic talent”1. But this is Florence and any emotion, even the most expressive, is subject to the control of reason. Banished are exasperations, contained by the disciplined levees of the intellect: in the words of Luciano Bellosi “it is not the staging of a drama but if anything, the silent contemplation of a drama.” From time to time connected to the Master of Santa Cecilia and Buffalmacco2, his activity is to be placed with verisimilitude in the middle of the second decade of the fourteenth century3.

There is no shortage of those who more recently have approached him to the Master of the Velvets4 but any attempt at identification is to be taken with due caution and our artist, to this day, stubbornly maintains his anonymity. We come to the work, which measures 152 x 128 centimeters and is thus smaller than the Uffizi work, recognized to be by the same hand. Useful is a comparison with the latter to hypothesize the shape of the cross which appears mutilated at the side expansions and the upper arm with cymatium. At the margins we have to imagine the mourners, the Virgin and the half-figured St. John the Evangelist. In 1984, the left terminal, that of the mourning mother, was identified in a private collection, a discovery that allowed a partial reconstruction5. Compared to the Virgin of the Uffizi, this one denotes a greater rhythmic fluidity of the border lines and a pronounced softness, factors that would seem to support the chronological placement of our crucifixion slightly later than the other. It is interesting to note that the hands are joined and that in this gesture there is a shift from the Eastern repertoire to the broader and freer influence of Western movement. Above, on the other hand, precisely in the cymatium, most likely stood the pelican in the act of ripping open its chest to feed its young. That of the mystical pelican is a motif perhaps imported in turn from the East and picked up by the cross painters of the fourteenth century6: it symbolizes the abnegation of God who sacrifices himself for his children; we find it in another work that Offner has attributed to the workshop of the Master of the Corsi Crucifixion, the one in the Allen Memorial Art Museum in Oberlin7.

The three works mentioned so far, Accademia, Uffizi and Oberlin, share another aspect on the carpentry front that, the writer, did not detect in the sources consulted. These are the diagonal segments, top and bottom (for the Oberlin cross, only the bottom) that join the transverse axis to the vertical axis. A detail, perhaps not diriment, but still common to the group of works considered to be by the Master, who tends to favor this silhouette (we find it in the crucifix No. 1655 by Giotto’s workshop at the Louvre, in that of Bernardo Daddi at the Accademia, painted about twenty years later, and in the crucifixion by Giovanni del Biondo exhibited by Robilant + Voena on the occasion of the aforementioned Biennale).

Let us come to the main subject: at the center is the Christus Patiens, with eyes closed, an iconography that predominates after 1250, and which gradually and definitively undermines the far-fetched, contrived and supernatural interpretation of the Christus Triumphans, alive, with eyes wide open. This is the apotheosis of the God Man, dying, suffering, undone, the Christ preached by the Poverello of Assisi. To the “Byzantine curve,” initiated by Giunta and exasperated by Cimabue, the fourteenth century responds with an important innovation that the Master of the Corsi Crucifixion adopts in the wake of Giotto and other coeval artists: the hanging Christ assumes a more natural, composed, aesthetic attitude. The body, we said, is no longer stretched in an arc but falls at rest with the muscles relaxed against the tree of the cross. The upper body, heavier, rests against the wood; the arms, pulled down by the weight, leave the horizontal position to accommodate this new lowered pose of the body falling in vertical motion; the knees are protruding, raised, folded8. The feet are now overlapping and nailed together (until the late thirteenth century they were separate)9. The hands leave forever the Byzantine pose, open, flat, to assume a more natural, saddened gesture. The loincloth, of light, transparent cloth, embellished with golden borders, belongs to the new fourteenth-century model: the knotting has in fact disappeared; the flap is now wrapped around the Crucified’s waist and, in its few folds, nicely shapes the body underneath. The Christ, as if of ivory, is speckled with ash in the lightest shadows, while the dark suddenly thickens by turning the side until it stands out against the geometries of the background. The multicolored carpet of Giuntesque origin, decorated with Mediterranean motifs of Islamic taste, is another element that unites not only Master Corsi’s crucifixions but also those closer to him in formal scansion, such as the crucifixions of San Felice in Piazza and Santa Maria Novella. And again the cross in the Malatesta Temple in Rimini and Giotto’s cross that once surmounted the iconostasis of the Paduan chapel, are a supreme and already fully matured example of the new type, in which Giunta’s vanished lyricism and Cimabue’s realism are kindled to an unprecedented spiritual life.

From these painted crosses, however, our Master differs by a certain harsh and anti classical naturalism10. The good condition of the pictorial layers has made it possible to document the original technical details, such as the rare quality of the glazed cinnabar in red lacquer relief and the silver foil decoration of the board. The paint is spread in veils over a shaded pattern: the tempera is so thin and delicate that the underlying foils emerge along the body of Christ. The Master of the Corsi Crucifixion follows the Giottesque only partially but resembles them in terms of the motif with interwoven elements profiling the tree of the cross. This is a widespread decorative theme from the first half of the thirteenth century that already appears in the painted one in the Uffizi Gallery (inv. 1890, no. 434)11 and, almost identically, in the Oberlin crucifixion already mentioned. This is a powerful and magnetic work: it imposes a visual, spiritual and emotional sharing on the part of the viewer, capable of imprinting itself on the most atheistic and jaded retina. After hundreds of years, Christ still leans toward a world that has not taken shape, with the vertigo, the lack of support, the sometimes pulled face of one suspended over an abyss. Yet, in all his fragility, he appears invulnerable: an immense figure of cruel wonder, in the sanctity of a prodigy and a spectacle no less sadistic than sublime.

- Richard Offner, “A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting”, Sec. III, vol. I, New York 1931, pp. 56-57 (Maestro del Crocifisso Corsi). ↩︎

- F. Zeri, Un’ipotesi per Buffalmacco, in “Diari di lavoro 1”, Torino 1971, 2a ed., 1983, pp. 3-5. ↩︎

- M. Boskovits, The Painters of the miniaturist tendency, “Corpus of Florentine Painting”, Sec. III, vol. IX, Firenze 1984, pp. 21-23 e 149; A. Tartuferi, Moretti, Maestro del Crocifisso Corsi, ed. Polistampa, p. 10.

↩︎ - A. Tartuferi, Moretti, Maestro del Crocifisso Corsi, ed. Polistampa, p. 13. ↩︎

- Cfr. footnote 3. ↩︎

- E. Sandberg Vavalà, La Croce dipinta italiana, Multigrafica Editrice, Roma, ristampa 1985, p. 89; per il simbolo del pellicano cfr. l’evangelario n. 5 della raccolta Sevadjian a Parigi (Macler, Documents, tav. XXIII, 52). ↩︎

- Scheda 5042, Fototeca Zeri, come anonimo fiorentino XIV sec. ↩︎

- Michele Bacci e Caterina Bay, Giunta Pisano e la tecnica pittorica del Duecento, Edifir ed, 2020, p. 81. ↩︎

- E. Sandberg Vavalà, Uffizi Studies The Development of the Florentine School of Painting, Leo S. Oslchki, Firenze, 1948, pag. 3 nota 3. ↩︎

- Miklos Boskovits e Angelo Tartuferi, Dipinti dal Duecento a Giovanni da Milano, vol. 1, p. 144, Ed. Giunti. ↩︎

- A. Tartuferi, Il Maestro del Bigallo e la pittura della prima metà del Duecento agli Uffizi”, Firenze 2007, pp. 41-45; per il motivo decorativo, cfr. F. Pasut, Ornamental Painting in Italy (1250-1310), An Illustrated Index in “A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting”, Firenze 2003, p. 81, 83. ↩︎

October 31, 2023