Andrzej Steinbach, a tautology of the ideal

Andrzej Steinbach invites us to relate to our systems of meaning allocation, so that images can vibrate free and open to understanding

What is photography made of? It is made of photography. That is why to reason about the images that Andrzej Steinbach creates one should take a precise perspective, namely that of the medium in hand. The question, however, is whether photography can still be regarded as a medium. We briefly discussed this with Steinbach during a meeting at the Briefing Room in Brussels, a space run and curated by Andrzej Steinbach and Steffen Zillig (here is the link to the project website). In fact, from the moment digital cameras became widespread (in the last decade of the last century), and then with the eruption of social networks, which induced us to continuosly share images of a photographic nature with anyone on the Earth, and again, with the evolution of photo editing softwares, the camera has been paired with a series of other tools that, in theory, would have every right to be considered as mediums in themselves.

Thus, does it still make sense to talk about photography as one talks about painting, sculpture or film? In the case of Andrzej Steinbach’s work, most probably so. But it is only possible after realising that it is the will to be photography that makes photography, not a photosensitive device of any kind, or a certain software. Therefore, if it is true that photography is made of photography, it is also true that it takes a photographer to take a photograph, namely a synthesis of technical skills and poetic needs. In times of Artificial Intelligence it is evidently pointless to reason about the former. Instead, we are interested in the latter, that is what allows us to understand why a photograph is what it is, hence why certain images, and not others, have the expressive complexity of artworks and it is therefore appropriate that they flow through books, galleries, and art institutions.

As noted by Lucy Gallum, who in 2018 included Steinbach in the New Photography series at the MoMA and then wrote an thoughtful essay for the catalogue of Steinbach’s solo show at the Kunstverein in Hamburg (2022, link), Andrzej Steinbach’s poetic design looks at our times with a clear understanding of the “models and protocols” of photography, but also of design, art, and fashion (by the way, Steinbach points out that the walls of his show at the Kunstverein Hamburg are actually old panels he retrieved from the institution’s storage and readapted as display tools bearing traces of previous exhibitions).

The portraits in the series Figur I, Figur II (2016), part of a trilogy that also includes the photographic cycles entitled Gesellschaft beginnt mit drei (2017) and Der Apparat (2019) – published by Spector Books in three separate volumes (link) -, almost completely negate the context in order to focus on the subject, that Steinbach in this way invites us to ‘analyse’. The observation mode might be reminiscent of the way we would watch a fashion shoot, where the model is a constant, while poses, clothes and accessories change. Except, of course, that there is no promotional purpose here. The subject’s attributes are completely neutral, brutally impersonal, devoid of subjectivity, just like the models in most professional fashion editorials. Yet this role swap does not lead, as one might expect, to the prominence of the individual, who instead of becoming a person remains an archetype. Rather than to an existentialist position, then, one lands in the territories of abstraction. The tautology of the subject leads to the absolute, to the ideal. Photography is made of photography, all the more so if it is in black and white, and if its pattern could repeat itself ad infinitum, like a Dreher glass or an Albers painting, which vibrate with meanings precisely because they exclude none. The same applies when Andrzej Steinbach focuses his attention on objects, or their interactions.

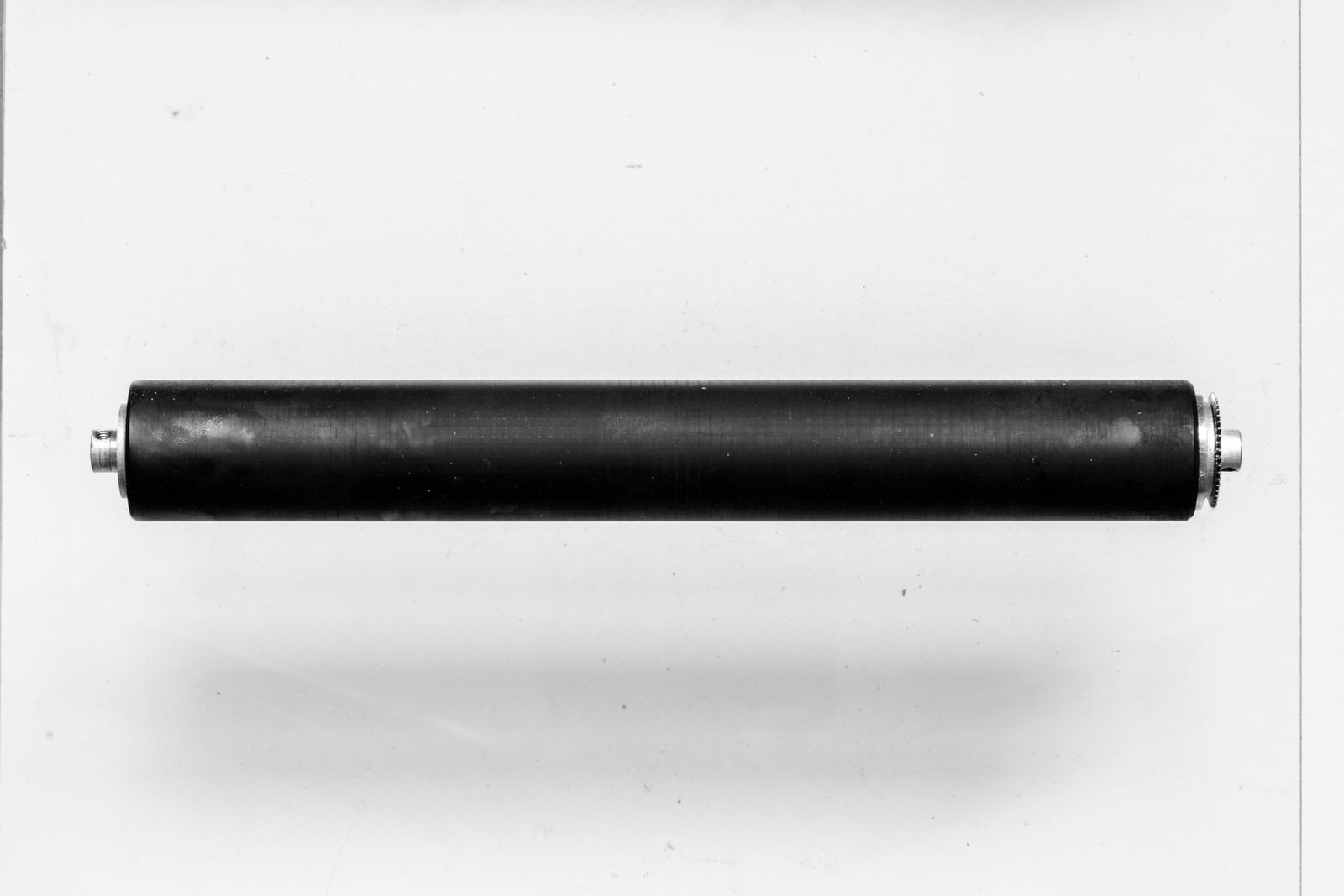

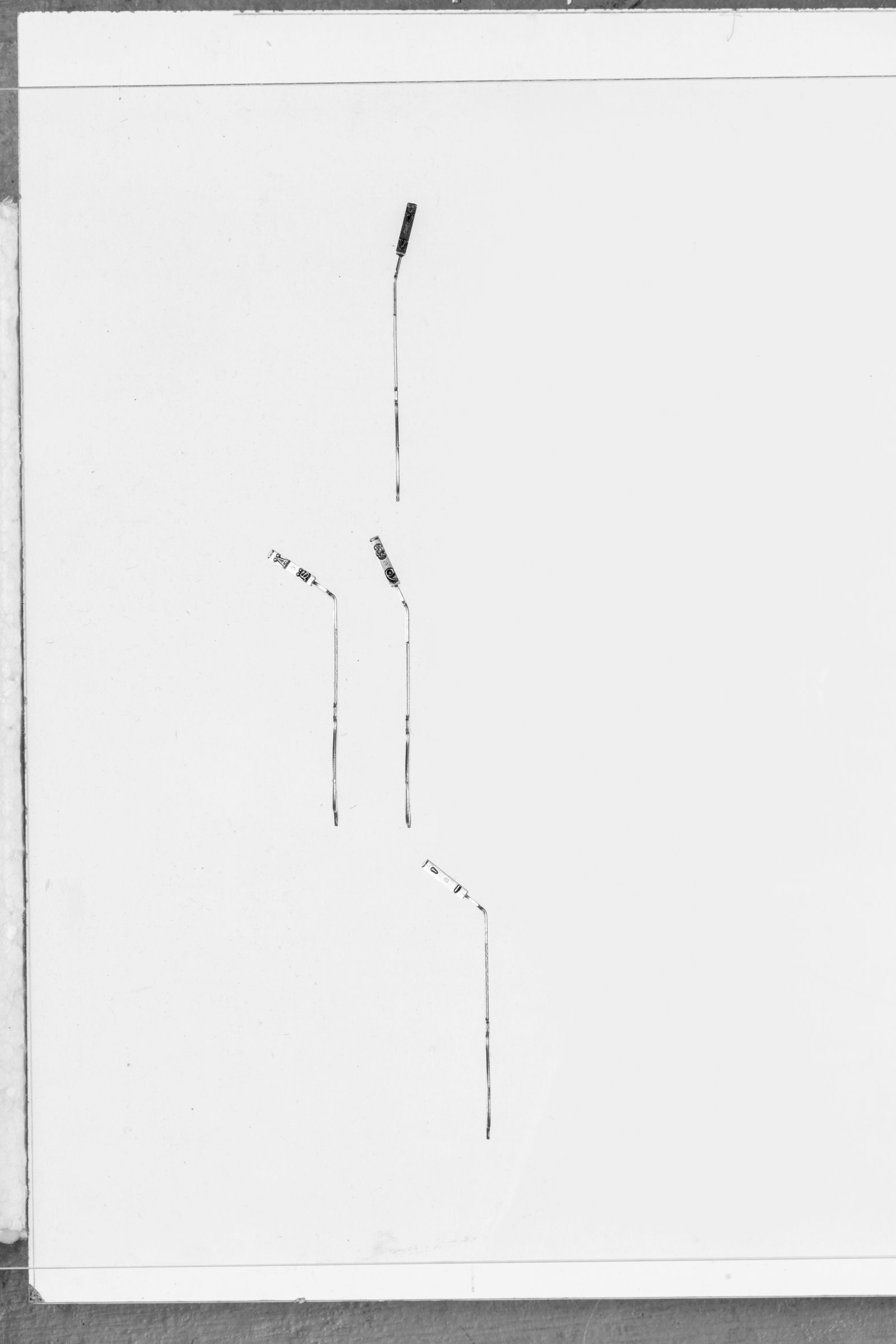

The character levers of a typewriter (Disassembling a typewriter, 2022) do not become, through photography, symbolic tools to address language, technological evolution, the struggle to express oneself, or the sense of nostalgia that the most nostalgic might feel. Rather, they are objects that photography invites us to relate to our systems of meaning allocation, so that they can vibrate in the absolute space, free and open to understanding. And so stones (Ordinary stones, 2016), nails (300 Nails, 2019), work tools (Auto erotik, 2022).

At a certain point, if anywhere, it is the pure forms that become symbolic. A curve, a knurled surface, a circle, the spontaneous volumetry of a human body caught in a certain posture. Implicit geometries masquerading as ordinary objects. That of Andrzej Steinbach is a poetics that works by means of subtraction of identity, and by temporal suspension. A decade after their production, in fact, the shots in Figure I, Figure II are still untouched, and the same could be said of all the series that have marked Steinbach’s production to date. Like untreated stones that don’t change in time; until someone passes by and gives them a glance. A stone, after all, is also made of stone.

May 8, 2024