Amy O’Neill: costumes for disappearing

The practice of Amy O’Neill moves according to a politics of the residual; costumes, masks, reversed parades are what remains when identity collapses.

In Amy O’Neill’s practice, art becomes a form of inquiry: what remains of a culture when its representations dissolve? The artist offers no answers, but assembles a posthumous iconography composed of disguises, relics, and absent bodies. She lays bare the childlike choreographies of national identity, transforming them into suspended fragments, to be observed without illusion. Born in the rural heart of Pennsylvania, O’Neill carries the province in her gaze and a residual America in her gestures: hers is an art of reconstruction and waiting, made of fragments, found objects, and faded reels that stubbornly keep narrating. Every object in her work — costume, mask, faded photograph, discarded parade float — bears a double temporality: on the one hand, the euphoria of the collective gesture that produced it; on the other, abandonment, stasis, the loss of function. Childhood, in her vocabulary, is never a place to be nostalgically reclaimed: it is a cultural structure, a device of incorporation. It is the space where the codes of visibility are learned, the postures of the public body, the rituals of community. But it is also the place where those same codes, when looked at closely enough, begin to unravel.

The recent exhibition This’s and That’s (Den Frie, Copenhagen, 2025), curated by Laura Gerdes Miranda in collaboration with Line Ebert and Gianna Surangkanjanajai as part of the OSLO program, is a clear expression of this. Not so much an installation as a suspended architecture of gesture. Fabrics, patchworks, ritual garments, and drapes are mounted on a system of pulleys that seems to belong to a long-forgotten ceremony — a ritual without religion. The costumes hang in wait for a gesture, and the masks do not conceal the face but rather double it. Viewers are not invited to interpret, but to touch, to wear, to release.

In STRAW MAN Vestment (2025), Goya’s “Straw Manikin” — so often read as an allegory of collective inertia — becomes an inhabitable costume: icon and body coincide, image and flesh contaminate one another. It is here that a field of deeply political tension emerges. Judith Butler, in her work on the performativity of gender and identity, has emphasized how acts that seem to express an identity in fact retroactively constitute it. Every garment is a gesture: a possibility of embodying what precedes us. In Amy O’Neill’s work, the ritual garment does not reveal an identity but overflow it, casting it into uncertainty. There is no role to affirm — only a sequence of gestures that render visible the very act of appearing.

Thus, in her work, carnival is never a simple joyful inversion. It is a zone of ambiguity, a suspension of the normative regime, where masks and costumes do not function as disguises but as paradoxical revelations. This is clearly demonstrated in the figures of DIE MASTER SCRIM (2025), — a title that plays between the verb “to die” and the enigmatic imperative of an invisible authority (“Die, Master”). Fluorescent panels are populated by televisual icons — Witchipoo, Arthur Herbert Fonzarelli, better known as Fonzie, the Evil Queen — standing out as floating icons of a popular mythology that has ceased to believe in itself. It is an ersatz procession, devoid of faith and yet still ritualistic.

In SERPENT LOOK (also 2025), a semi-transparent scrim—typically used in theatre to create effects of appearance and disappearance—acts as an ambiguous stage curtain or scenic veil. It features a silkscreened green serpent writhing over traces of Go, the ancient Chinese strategy game—or, in its Indian moral version, Snakes and Ladders. Through this act of superimposition, Amy O’Neill retrieves and distorts an ancient symbolic system: the serpent is no longer merely an emblem of sin or moral descent, but also a symbol of ambiguity and metamorphosis. In both works, the artist uses humble materials and references drawn from a desacralized pop dimension. There is no nostalgia, nor irony. Rather, a distorted form of pietas towards what remains when the imaginary crumbles: games, superstitions, illusions of moral control. Temporality is layered, never linear, unfolding through elliptical montages—both visual and emotional.

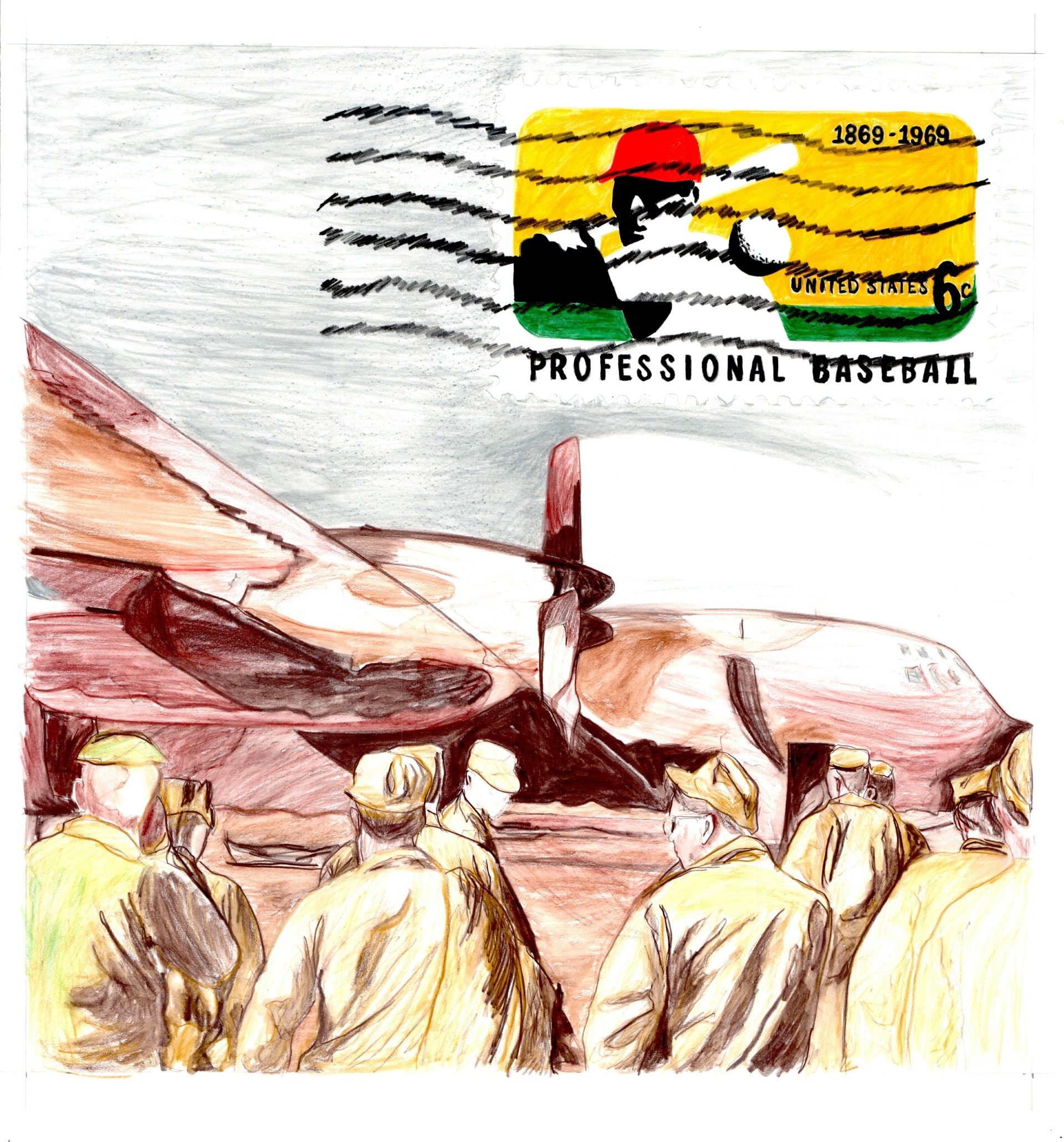

Between 2015 and 2016, Amy O’Neill created Vietnam or the American War, a series in which the war—never experienced firsthand but obsessively narrated—becomes a mental landscape. There is no attempt at historical reconstruction here, but rather a process of excavation within the American collective imaginary: toy helicopters, faded photographs like memories memorized by rote. America reveals itself in the folds of rusted tin, in the swings built by soldiers for their children, in Polaroids that remain glued in place even when they show nothing anymore. Everything is rendered in miniature, like a trauma made child-sized. The war is a visual device learned through media—through films, television, patriotic school lessons. It is a conflict internalized as spectacle, and thus all the more unsettling. We did not fight that war; we absorbed it in the form of plastic and cardboard, through classroom models, evening news broadcasts, the fake jungles of afternoon films—a story told by those who weren’t there, in the broken voice of someone who knows that even myth is a wound. Amy O’Neill does not denounce, nor does she commemorate: she stages the confusion between document and fiction. And in this synthetic memory, built from culturally shared yet affectively ambiguous images, childhood returns as a site of ideological sedimentation. The conflict, stripped of its direct horror, survives as a relic in faded plastic, in the opaque dream of television.

This gesture of childhood, this wounded grace, had already been staged elsewhere by O’Neill. In Dijon, with Parade Float Graveyard (Le Consortium, 2006), she built a cemetery for America’s allegorical floats. Reconstructed by hand, faintly lit, and presented not as artifacts but as ghosts, they inhabit a liminal space. There is a Noah’s Ark, but it is empty; a tiered cake, but the cherries have fallen; the wheels no longer turn, and the decorations are crumbling. Ghost Float (2004), The Golden West (2006), The Granddaddy of Them All (2005) — are relics of a faith turned papier-mâché. Inspired by actual American folk parades, especially the Rose Bowl Parade, these simulacra now appear as monuments without triumph. They do not document the event; rather, they evoke its residual persistence. The American dream is not destroyed, but suspended in a state of opaque visibility: still there, both inaccessible and excessive.

Her work on childhood is neither biographical nor nostalgic; rather, it is an inquiry into how cultural diapositives shape the body, the voice, the gesture. At every point in her practice, there is a presence of childhood — but it is never her own. It is everyone’s childhood: the collective one, domesticated, trained in visibility, made of small things that first become mythology and then debris. When asked whether for her “childhood is a place one returns from, or a place where one is lost forever,” she replies: -“Neither of them. There is no escape from childhood. It can be repressed but not erased. It’s a condition of our lives. I fully embrace the idea that memories are constantly re-fabricated as we age, and that they ultimately become shared ones. My work might also point to the progressive dissolution of the singular into the collective—to what eventually brings us together, whether we like it or not”-.

If Vietnam or the American War traced an interior map in which war became a memorized narrative, Zoo Revolution opens that same childhood as a fractured dream: no longer merely the theatre of trauma, but a visual space where lost images resurface, fragmented, like nocturnal animals in search of shelter. Zoo Revolution (2006–2019) is a looped video shot on 16mm and later transferred to HD, distilling over a decade of observations, visual drift, and the accumulation of filmic material. First presented publicly in 2019 at Paula Cooper Gallery in New York, the work unfolds as an elliptical and partly visionary archive, structured through the recursive rhythm of montage and a perceptual layering that rejects any narrative linearity. O’Neill overlays zoo footage into a kind of documentary dream. The animal is no longer the object of ethological contemplation, but a symptom of a broader crisis in vision itself: out of focus, multiplied, fragmented by the apparatus, returned in an archetypal yet deactivated pose.

The notion of “revolution” in the title carries no heroic connotation; it is, rather, a motion without direction, an iterative gesture that unsettles without overturning—evoking what Giorgio Agamben might describe as a “destituent power”: a suspension of meaning, a lateral departure from the language of images. Time, in its circular torsion, acts both as trauma and as palimpsest.

Zoo Revolution presents itself as an exercise in montage and survival: the moving image not as narration, but as an act of evocation and dysfunction, where the animal, the enclosure, the mechanical gesture, and repetition become critical operators of a memory without redemption—a field of inquiry into affective memory and its deceptions. “Work that has developed over 10 years gifts me layers, basements and subterranean histories that I am excavating,” writes the artist in the text 3Birth of The Zoo Revolution, thus defining a practice that is both archaeological excavation and mise en scène, a display of ruins and a creation of vernacular fictions. Animations—such as the one by Gerhard Fieber, identified through a marginal linguistic clue (the label Speisewagen DSG) and then linked to a visual production associated with Nazi propaganda—are grafted into the landscape of childhood as a form of contaminated innocence, revealing through friction its ideological fractures, latent historical currents, the ghosts that inhabit even the most seemingly neutral imaginarium.

Childhood itself, in this montage, is no longer an Edenic space but a stratified field where the aesthetics of entertainment bend toward an oblique function: that of depositing, in the form of visual enchantment, a narrative of power. In O’Neill’s work, found footage is never mere reuse: it is excavation, stratigraphy, contact with what reveals itself only for an instant—like the elusive “chicken lady” digitally unearthed in a period montage, or those schoolroom images glimpsed during a drowsy afternoon at Saint Peter and Paul Catholic school, which Amy herself attended. Time is never linear: it unfolds as a spiral of imperfect returns, a field of forces where memory and imagination become indistinct. The films themselves are constructed as heterogeneous montages: 16mm landscapes, vintage animations, family archives. The point is not narration, but atmosphere—a visual field where every image is already a specter. And at this point, a question emerges: “What happens when montage does not recompose, but fragments further?”. “The point of montage, for me, is not to recompose a new ‘reality,’ but to embrace the fragmentation of memories and thoughts as they recede into time. Entropy is always a powerful force at work, and I see no reason to fight it”, O’Neill replies.

Amy O’Neill’s entire practice moves according to a politics of the residual. Her costumes, her masks, her reversed parades are what remains when identity collapses—yet its signs persist. They are forms-of-life, to borrow once again from Giorgio Agamben: not styles, not subjectivities, but fluid configurations in which life and form coincide without the possibility of separation. O’Neill does not offer alternative identities, but rather experiences of disidentification: gestures of withdrawal, of slippage, of rendering opaque what dominant culture demands to be transparent. And perhaps it is precisely in this state of suspension that the power of the gesture lies. There is never celebration, nor denunciation—only a slow procession of remnants that do not cease to signify. An America that continues to stage itself, even when no one is watching anymore. Amy O’Neill reconstructs that abandoned theatre to show us how, even in the unmaking of every form, something still pulses. As the mask detaches and the costume slips to the floor, only the gesture remains: someone who looked, gathered, unveiled.

And left us the quiet possibility of disappearing with grace.

September 3, 2025